London’s first party boat!

Posted by Chris Graham on 30th October 2021

Richard Clammer recalls the unusual history of an 1879 paddle steamer that became London’s first party boat!

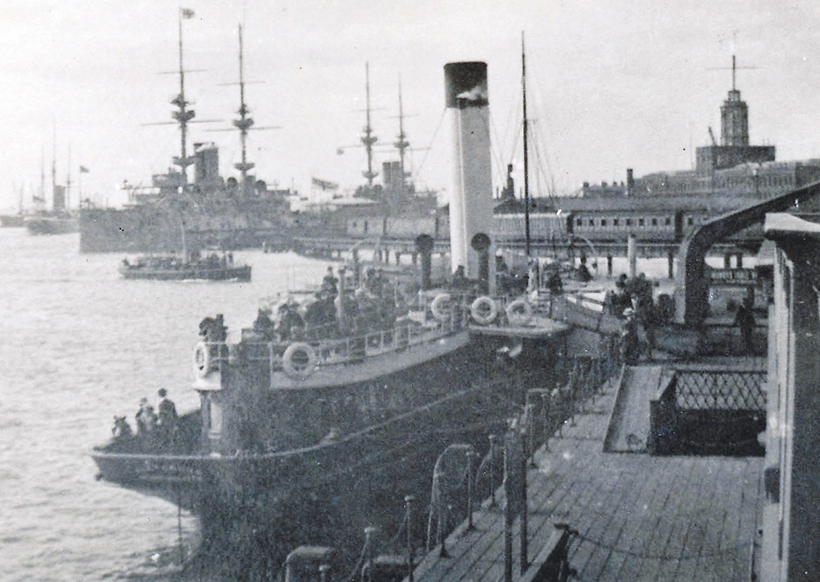

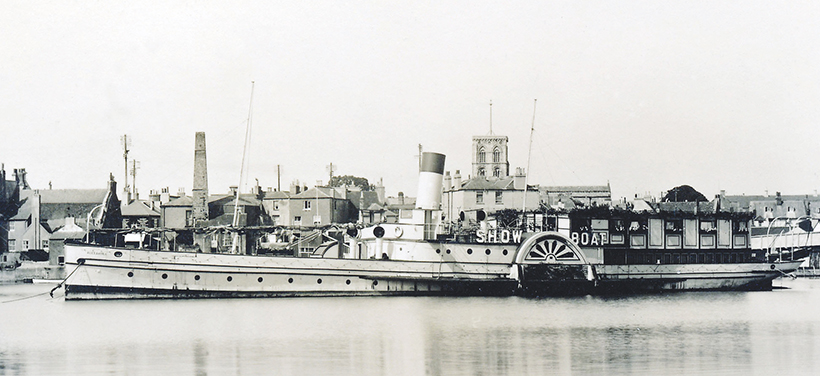

London’s first party boat!: Alexandra at Portsmouth Harbour station during her years on the Joint

Railway Committee’s Portsmouth-Ryde ferry service.

In April and May 1932, the society and gossip columns of the London press were abuzz with rumours of the imminent arrival of a fashionable new Thames attraction. Billed as the ‘Show Boat’, the vessel concerned was actually the former south coast paddle steamer, Alexandra, which was being heavily modified to provide cabaret, dancing and dinner cruises from Westminster Pier ‘in the best American Mississippi tradition’ and, thereby, establishing herself as London’s first ‘party boat’.

Alexandra had been launched in April 1879 from Scott & Co’s yard in Greenock, to the order of the Port of Portsmouth & Ryde United Steam Packet Co Ltd. Built of iron, she was fitted with a two-cylinder compound diagonal engine giving her a trial speed of almost 15 knots. In the style of the time, she had an open foredeck, a narrow deck saloon aft with walkways around the outside, and a promenade deck above.

Soon after Alexandra had entered service between Portsmouth and Ryde in June 1897, her owners were bought by the London & South Western Railway and the London Brighton & South Coast Railway, and a joint committee was formed to operate the ferry service.

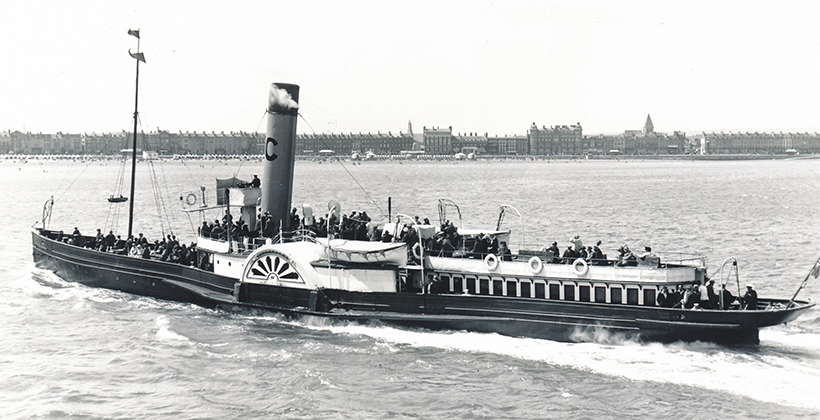

Having left Brixham and called at Paignton and Torquay en route, Alexandra sweeps into Weymouth Bay during one of her regular weekly long day trips. The photograph was taken between 1924 and 1927, when Cosens based her on the South Devon Coast and a large C was painted on her funnel.

Alexandra was re-boilered in 1892 and sailed on, without any recorded dramas, as part of the joint fleet until 1913, when she was withdrawn and sold to the Bembridge & Seaview Steam Packet Co and used for service between those Isle of Wight villages and the mainland. Unfortunately, she proved too large for Bembridge harbour, so she only served for one season before being placed on the market again.

On July 29th, 1914, she was purchased for £1,350 by Cosens & Co Ltd of Weymouth, which was seeking an additional steamer to help meet the booming demand for south coast excursion sailings, and serve as a liberty boat to the Naval fleets at Portland. During the First World War she served as an Admiralty ferry between Sheerness and Gillingham on the River Medway, from 1915 to 1919, being renamed HMS Alexis from March 1916.

After the war, and following a thorough refit, she re-entered passenger service during the summer of 1920, running excursions from Bournemouth, Weymouth and, between 1924 and 1927, Torquay. In November, 1930, she was placed on Cosens’ slipway for her Board of Trade survey, but was refused a further certificate unless extensive repairs were undertaken.

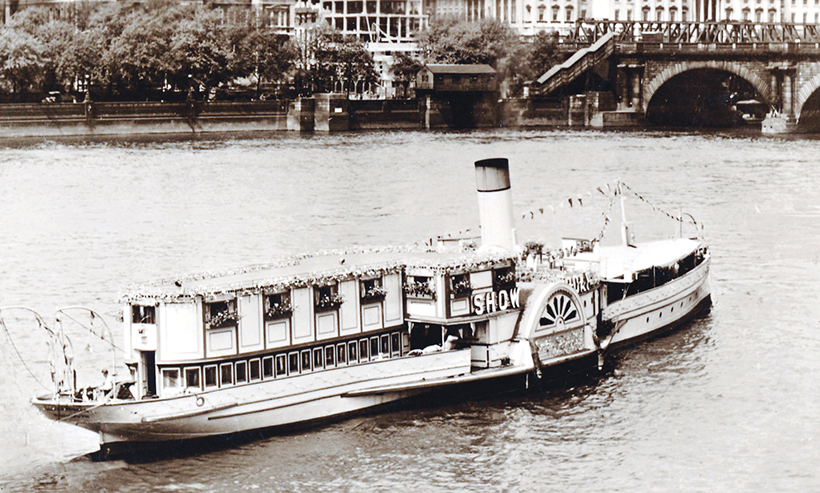

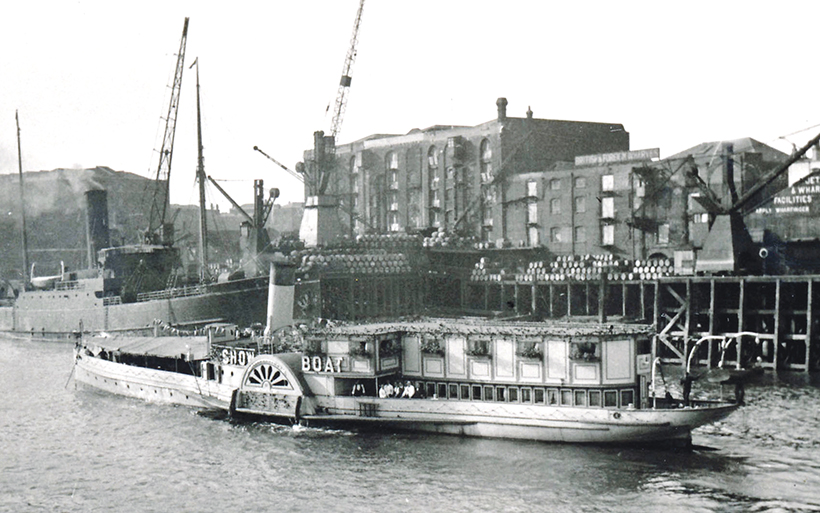

Show Boat, complete with dance hall, fairy lights and floral displays, poses for an official photograph on the Thames in May or June, 1932. The image appeared on a promotional postcard which was widely available at the time.

It was decided that the condition of the 52-year-old ship, combined with the generally depressed state of trade, didn’t justify the expenditure, so she was advertised for sale. In January, 1931, she was sold for £335 to Pollock Brown & Co Ltd, and delivered to its Southampton shipbreaking yard a few days later. It was assumed that this was the end of the line for an elderly, hard-worked pleasure steamer but, in fact, the most exotic period of her career still lay ahead.

On February 8th, 1932, she was purchased by Captain Alfred Hawkes of Littlehampton, who promptly raised £900 by mortgaging the ship to Clifford Whitley of the Hotel Metropole, London, and James Rhodes, a mercantile marine officer. Whitley was a well-known theatrical impresario, director and producer, whose name was closely associated with the Midnight Follies revue.

The new owners’ plan was to put Alexandra into service on the Thames as a floating dance hall and cabaret. The old ship was slipped at Southampton, where enough repairs were undertaken to persuade the Board of Trade that she was safe to operate. Her tall funnel and masts were replaced by shorter ones, her raised bridge was removed, and her wheel and telegraphs relocated to the forward end of her promenade deck, where two new bridge cabs were also fitted. An enormous dance hall-cum-theatre was erected on top of her aft saloon, her decks were re-laid to make them suitable for dancing, and the foredeck was covered by a large awning.

Alexandra arrives at Bournemouth Pier, summer 1920, shortly after Cosens’ post-war excursion sailings had been resumed. Fleetmate Monarch undertook the longer trips, while Alexandra maintained the Bournemouth-to-Swanage run.

By May 25th, 1932, she’d arrived in the West India Docks for her advertised debut on May 30th, which took the form of an evening charter to Nash’s Club of Savile Row. Top orchestras, well-known cabaret artistes, wine cellars, cocktail lounges, a dance floor and fine dining were all promised at ‘ordinary West End prices’. Additionally, in contrast to the strict licensing regulations ashore, once Show Boat had cast off, drinks could be served at any hour of the day.

Clifford Whitley’s advertising campaign clearly struck a chord at a time when south-east England was just beginning to emerge from the dark days of the depression. The ‘notables’ of London society found Show Boat to be an irresistible distraction. Bookings rolled in and, within a week, she’d established a regular pattern of operation.

All regular trips headed downstream as far as Gallions Reach and back, a distance of 30 miles. Show Boat, herself ‘gay with masses of flowers and myriads of coloured lights’, certainly stood out among the commercial shipping. At 171ft, she was considerably longer than the average Upper Thames pleasure steamer of the day, and it must have taken considerable skill to spring her off Westminster Pier, turn her in the fast-flowing river and then shoot the various bridges on the way downstream, often in the dark.

The Master for her first few weeks in service was the same Captain Alfred Hawkes who had purchased her from Cosens, but, on July 4th, he handed command to Capt HF Defrates; one of an extended family of watermen, mariners and pilots living in the East End of London.

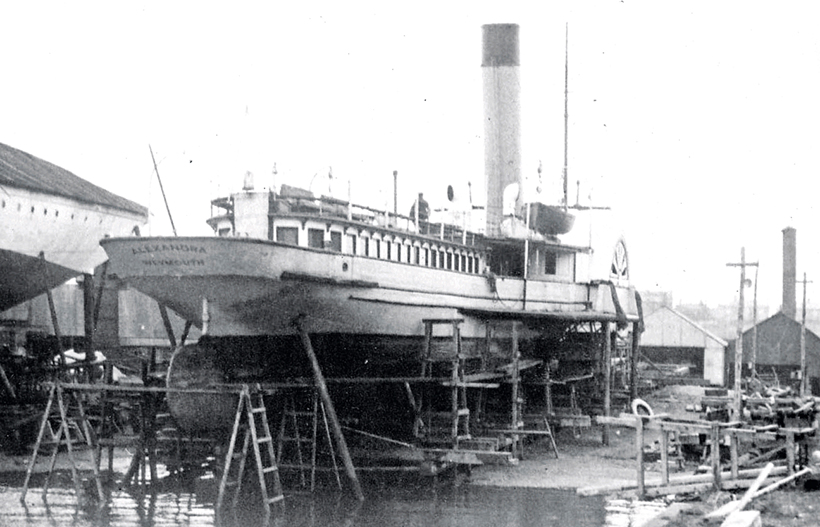

Alexandra on the slipway at Southampton for hull repairs in February 1932, prior to her conversion into Show Boat. Here her hull has been repainted, but no structural alterations have yet taken place.

Show Boat proved extremely popular throughout June and July, her regular trips being punctuated by a series of widely-publicised ‘floating garden parties’, ‘dress, bathing suit and mannequin parades’ and social events. However, as the September evenings began to draw in, the Thames seemed a less hospitable place, the novelty began to wane and the fashionable set drifted away.

With the ship laid up for the winter, financial analysis revealed that her very heavy expenses – including a reported £450 weekly wage bill, plus £80 per week to use Westminster Pier – meant that she’d failed to make a profit. This fact was underlined when Clifford Whitely was summoned for non-payment of pilotage dues, together with the manager of the Show Boat for failure to settle other bills.

With a second season at London out of the question, Clifford Whitley cast about for a viable alternative, and settled on the bizarre idea of sending the ship to continue her showboat career at anchor off Margate, where she arrived in June, 1933, and lay to two heavy anchors.

A Captain WE Harrison was in command and later wrote: ‘I can still remember the published remarks of a Margate City Father, who rather querulously wished to know: ‘how much longer this obnoxious Show Boat is to be tolerated in our midst? Some of the attempts to incommode us were directed well below the belt’.

Moored in the River Adur at Shoreham, during the summer of 1933.

Feelings ran high in Margate at the idea of a new vessel attempting to join the local tripper/catering fraternity during a depression year. It would appear that, by simply refusing to ferry customers to and from the shore, local boatmen ensured that her stay lasted for only a matter of weeks.

By mid-July, the ship had arrived at Shoreham-by-Sea in Sussex, and was moored about a mile up the River Adur, directly in front of the town centre and just upstream of a wooden footbridge, which led from there to the Bungalow Town, which was being developed on the coastal spit of Shoreham Beach. An application was lodged with the Harbour Trustees to open her as a static club, and a permanent gangway was constructed to link her to the shore. Clifford Whitley’s name didn’t appear on the application but, among those cited were two of his business acquaintances to whom he had let the ship, the owner of Romanos’ Restaurant and a Mr Stuart, manager of Murray’s Club in London.

The formal opening of the Showboat Club took place on Saturday, August 5th, 1933. The local magistrates granted a special extension to licensing hours to mark the occasion, and temporary music and entertainment licenses were issued, but attempts to make the arrangements permanent were scuppered when the police began to receive complaints from local residents about excessive noise after 22:00 on dance nights.

Applications for further late night extensions during September were refused, and the club closed. The possibility of making a profit in such a relatively remote location, at some distance from large, fashionable centres of population, must always have been a faint one.

A close-up of the run-down Alexandra at Shoreham, in 1934.

Show Boat remained in her mud berth on the south side of the river under the care of her ship-keeper, Captain Harold Quick and his wife, until the spring of 1934, when a team of engineers and craftsmen from a London ship-repairing firm arrived to prepare her for further service.

It was reported that she was in the process of being purchased by a Captain Andrew Hardie, who intended to introduce a programme of return cruises from Trafford Wharf, Manchester, along the length of the Manchester Ship Canal and out into the Mersey Estuary for a fare of 5s 6d. Show Boat’s ‘magnificent dining saloons, ladies’ lounge, American Bar, ballroom saloon’, and exotic appearance, made her ideally-suited for his purposes.

For a week or two the ship was a hive of activity, steam was raised and, during May, 1934, a skipper and delivery crew arrived to steam her round Manchester. Advertising leaflets were issued and advance bookings began to roll in, but then all activity ceased. It emerged, as one newspaper put it, that ‘one of Captain Hardie’s regrettable failings is the way in which he gives cheques without due consideration of the funds available to meet them.’

With her show boat days over, Alexandra lays in her mud berth at Shoreham-on-Sea awaiting a new buyer, late 1933 or early 1934.

The cheque for the first instalment of the ship’s purchase bounced, the ship repairers were unable to obtain payment of their £200 bill and the unfortunate crew, their credit with local tradesmen exhausted, were stranded on board without wages or food, and were forced to join a long queue of creditors and out-of-pocket backers.

The ship returned to her slumbers on the Shoreham mud bank for the remainder of the summer. Despite their best efforts, Clifford Whitely and his chief mortgagee, Sir Malcolm McAlpine, failed to find another buyer or lessee who was prepared to operate the ship, so sold her to TW Ward Ltd for breaking at Grays, on the River Thames.

On October 25th, 1934, crowds of local residents turned out to watch her inch, stern-first, through the Shoreham footbridge, which suffered slight damage in the process, and then set off under tow for her final voyage. Steamers in port saluted her with their whistles as she passed silently on her way and, as one observer recorded, ‘upon reaching the open sea, she dipped gracefully in the moderate swell as if paying her courteous respects to the harbour that had sheltered her in her final years.’ With demolition completed, her register was closed on December 19th, 1934.

Laying at her overnight moorings, Show Boat prepares for another busy afternoon and night. A group of stewards on the port sponson have taken a short break from their duties to watch the photographer’s ship pass by.

Although 51 of her 55 years were spent quietly and efficiently discharging her duties as a ferry and pleasure steamer, it is perhaps inevitable that the little Alexandra is best remembered for her two colourful years as Show Boat, which earned her a small place in maritime history as London’s first ever party boat.

For a money-saving subscription to Ships Monthly magazine, simply click here