The power of Rimpull

Posted by Chris Graham on 28th February 2020

Nick Baldwin takes a look at the power of Rimpull, one of the main suppliers of dumptrucks to the US surface-mined coal industry.

The power of Rimpull: the biggest of the two-axle models in the late 1980s was this 130-ton capacity RD-130, with a 1,350hp Detroit or Cummins engine.

The all-critical brake horsepower and torque is measured on giant earth-mover wheels at their rims. Thus, tractive effort, commonly known as rimpull, is far more important than the gross output of the engine, as it shows how efficiently the power is put to work.

Earthmoving contractors had long known that chain-drive, with the biggest possible sprocket at the wheel, reduced shocks on the transmission, and fed the power in smoothly to minimise wheelspin. The trouble with chains was that they were vulnerable to grit, and fed this damage back to the driven transaxle. Attempts were made to cover chains in oil-filled chaincases, but these tended to hit rocks and break. Despite the drawbacks, the benefits of chain-drive continued on Macks and Sterlings into the 1950s.

Maximum rimpull

Another way to achieve maximum rimpull was to fit reduction gearing in the wheel hubs, as done successfully on mainstream trucks in Britain by Albion, in the 1950s. This allowed smaller and lighter transmissions and half-shafts to achieve what had previously needed heavy components. Hub reduction became a must on big American dumptrucks, even when they were diesel-electric machines with wheel motors.

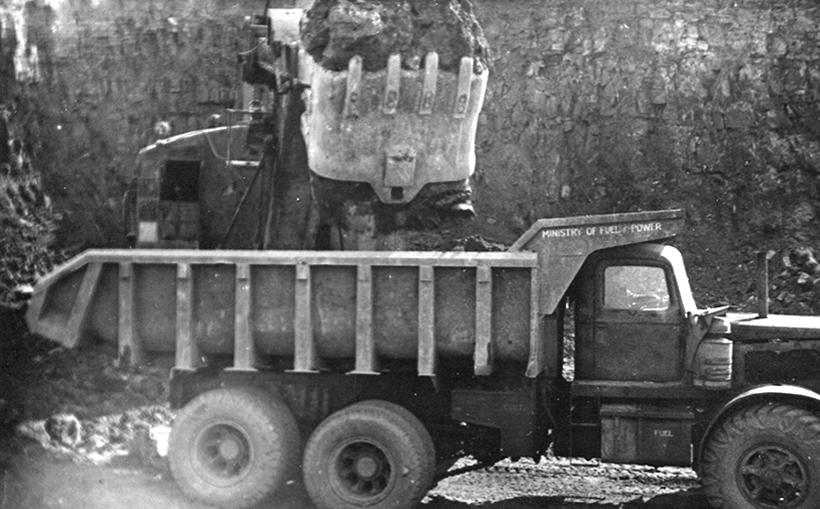

A Mack from about 1950, with maximum tractive effort at rims achieved, in this case, by chain reduction.

Around 1960, a firm in Kansas which supplied replacement parts for earthmovers, began development of a triple-reduction replacement axle, which turned out to have many of the plus points of chain-drive, but without the problems. By the time that Rimpull, as it had become (based at Olathe, Kansas), was ready to build its own dumptrucks in 1971, it could supply treble- or even quadruple-reduction thanks to an extra step-down in the back axle differential housing. It delivered its first two dumptrucks able to carry 100 tons in 1973, and had made 100 machines by 1980, with some 75 of them at 100 tons and over.

A 1000hp RD-100 dwarfs Rimpull’s Chevrolet service truck in the mid-1970s.

Rimpull favoured mechanical rather than diesel-electric drive, and it incorporated Allison six-speed powershift gearboxes behind its Cummins or Detroit diesels. Each vehicle was tested for eight to 10 hours on the company’s own test track before sale. The firm became the biggest supplier to the US surface-mined coal industry, which favoured bottom-dump, and either rigid or artic six-wheelers. Haul roads tended to be steep, and the ground uneven, and these layouts proved to be the safest because of the lowest possible centre of gravity.

Dust quenchers

Rimpull also made 15,000- and 20,000-gallon, two-axle water carriers to quench the dust of these big pits, at the rate of 10 miles of 70-foot-wide roadway, or 80 acres of pit floor, in less than half an hour.

The 15,000-gallon WT Dust Masters had 600hp Cummins or Detroit diesels. The 20,000-gallon model used 700 or 900hp diesels from the same makers.

New in 1978 was the 120-ton capacity RD-120, with its radiator in line with the rear of the half-cab.

By the early 1980s, Rimpull was supplying dump and water trucks to 46 locations, worked by 23 of the biggest mining companies. In all, 336 pits and quarries worldwide employed Rimpulls, which had, between them, clocked-up over two million operating hours.

A proud claim was that components were as light and simple as possible, to ensure that anything could be rectified within one shift. There were 12 distribution points spread round the mining areas of Nevada, Arizona, New Mexico, Wyoming, North Dakota, Kansas, Texas, Alabama, Georgia, Ohio, Virginia, Illinois and Kentucky.

An unusual, but logical, feature of the big orange Rimpulls was that the Young radiator was next to the back of the half-cab, to keep it away from knocks and the worst of the dust. Being above the engine, it ensured a positive head of water, and improved visibility and engine access.

Many rivals had independent stub axles at the front, but Rimpull favoured a one-piece axle for improved alignment and tyre life. Early trucks had leaf springs, but Firestone Marshmellow, vulcanised multiple fabric-plied discs were soon specified, as they were cheaper to repair and adjust.

The CW-150 had a 1,050hp Cummins or 1,000hp Detroit, air-started diesel, with Allison transmission and quad-reduction.

By the mid-1970s, the rigid trucks could handle up to 120 tons, and the articulated ones, 170, both with 1,000/1,200hp diesels. From 1978, the biggest had 1,200hp and a 200-ton capacity as an artic, or 120 tons as a rigid. The rigid sixes by then spanned 700hp 70-tonners up to 1,050hp 100-tonners, primarily for coal haulage.

In 1990, Peabody Coal’s Lynnville pit in Indiana, took delivery of the biggest of all Rimpulls. It consisted of a 1,500hp V12 Detroit-powered hauler, with a 150-ton capacity semi-trailer, behind which was a two-axle, 120-ton, bottom-dump semi-trailer.

Too unwieldy

The outfit was 150 feet long and grossed almost 900,000lb, with a 353 cubic yard load, but proved to be unwieldy and difficult to turn. After a while, it was split, and became two separate machines. Rimpull made some even bigger, artic bottom-dumps for Peabody, with a 280-ton capacity, though these were pulled by either Caterpillar haul units or Darts, specially modified by Rimpull.

Rimpull’s own biggest hauler of the mid-1990s was for 180 tons, and 255 cubic yards heaped, and had a 1,350hp Detroit V12. After all the publicised advantages of a rear radiator, this had conventional front mounting, albeit leaning backwards at a jaunty angle to reduce overall height and increase forward visibility.

Rimpull’s production facilities by then covered much of a 68-acre greenfield site at Olathe, and its rugged and relatively simple dumptrucks were being exported all over the world. In the new century, Rimpull was among the leading producers of mechanical drive, custom-built dumptrucks and, also, had an engineering team able to improve the performance and serviceability of other makes of truck – not least by fitting its own multiple-reduction axles.

If you’d like to subscribe to Classic Plant & Machinery, click here