HMS Hermes; the first aircraft carrier

Posted by Chris Graham on 6th December 2022

HMS Hermes is regarded as the world’s first aircraft carrier. James Hendrie traces the ship’s career from her construction to WWII sinking.

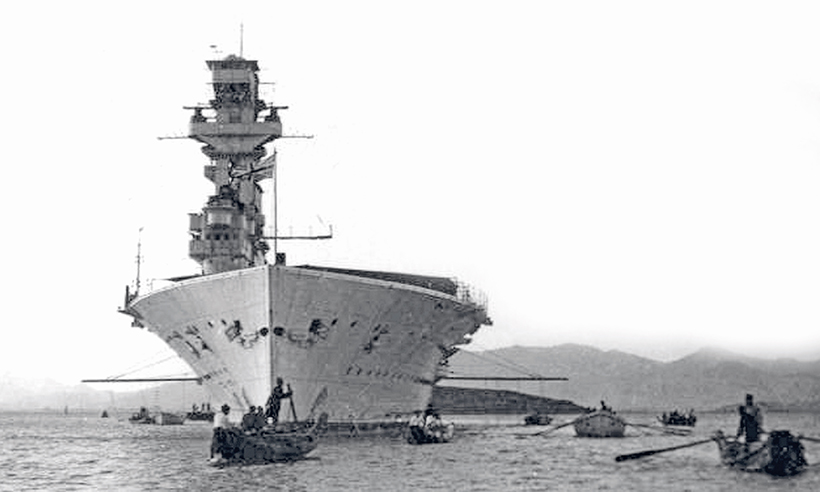

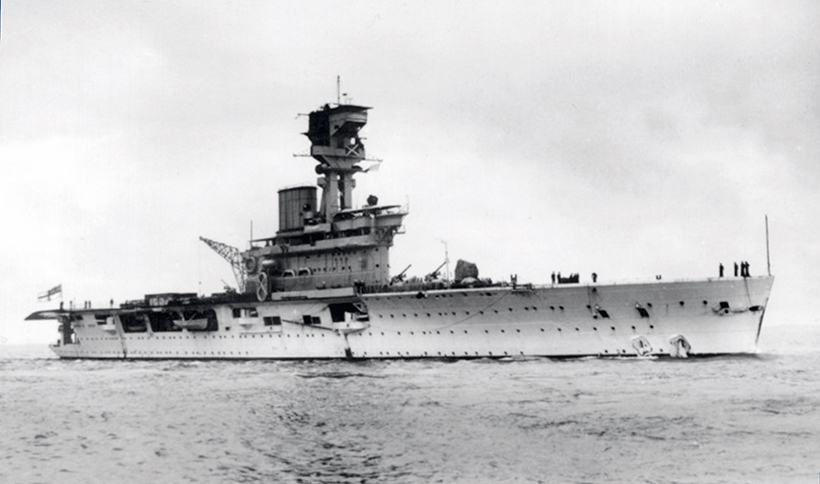

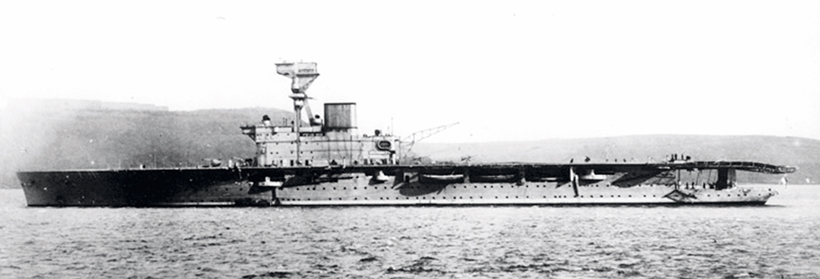

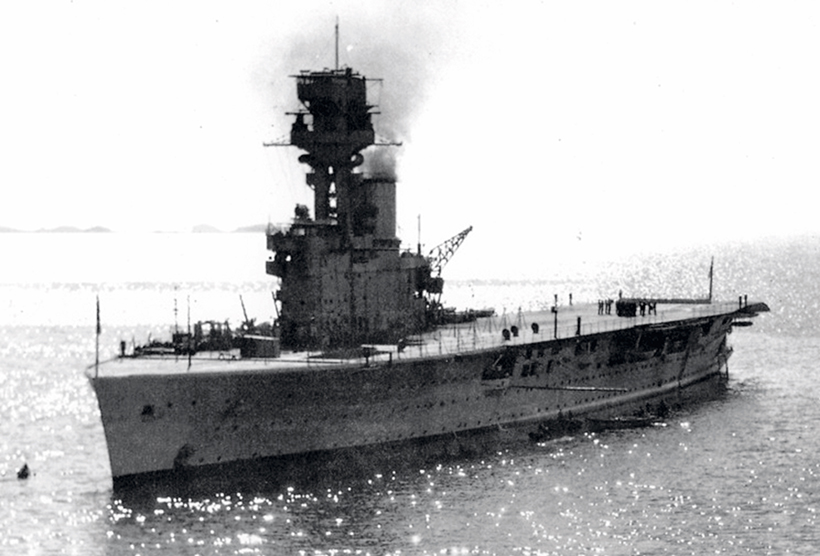

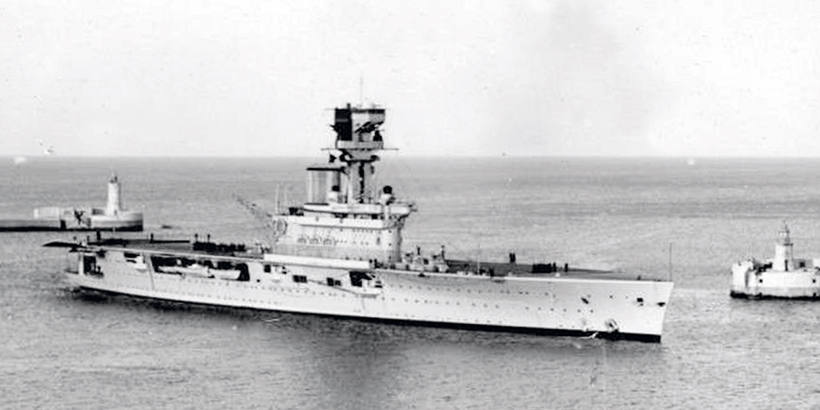

HMS Hermes was the first ship designed from the outset as an aircraft carrier. (All photographs copyright Michael W.Pocock/martimequest.com)

Eighty years have passed since the sinking of HMS Hermes, which had the distinction of being the first warship to be designed from the outset as an aircraft carrier. Hermes, ordered by the Royal Navy in April 1917, was launched on 11th September, 1919, but it took until 19th February, 1924, before she was actually commissioned. However, in the time between her being ordered and joining the Royal Navy, the Japanese aircraft carrier Hosho was completed and she, therefore, became the first purpose-built aircraft carrier to enter service.

Sadly, aircraft from a Japanese aircraft carrier strike force were responsible for the sinking of Hermes in the Indian Ocean, on 9th April, 1942. Eighty years on from that devastating attack by Aichi DA dive-bombers, the wreck of Hermes, located in the Bay of Bengal, can be dived. Hermes lies on her port side, with the main deck collapsed onto itself. Parts of the ship are still identifiable, notably a number of the guns used as her shipboard defence.

Hermes did not enter service until 1924, although she was laid down on 15th January, 1918. After she was launched, the Armstrong Whitworth shipyard which built her closed, and her fitting-out was suspended.

WM Armstrong-Whitworth & Co at High Walker in Newcastle principally built Hermes but, with this yard closing in 1919, she was moved to Devonport for completion. Hermes was 600ft overall, while her flight deck was 570ft, and her hangar 400ft long by 50ft wide and 16ft in height. Lifts moved aircraft to the flight deck, where there was arresting gear and a large deck crane.

Hermes had two sets of Parsons-geared steam turbines, each of which drove one propeller shaft, giving her a speed of up to 25 knots. Six Yarrow boilers powered turbines designed for 40,000shp. Hermes could operate to a range of 6,000 nautical miles, at 18 knots. Her armament consisted of six 140mm guns situated in her hull, three on each side, and three 102mm AA guns along the starboard side of her flight deck.

The delays in her building were due in part to the experiments carried out with early aircraft carriers to improve carrier design. In Hermes’ case, this led to her having a small hangar capacity and being unstable in high seas because of her large starboard island, where her bridge, funnel, command centre and masts were located. To counter this instability, fuel had to be carefully stored throughout the hull.

By the outbreak of World War II, Hermes was capable of carrying only 12 aircraft.

This island superstructure concept was innovative at the time. The rationale for the placement of the superstructure was so that the flight deck was unimpeded and that smoke and gases from the funnels were kept clear of the aircraft. The aircraft Hermes operated changed during her years of service. In the 1920s, when she first entered service, Fairey Flycatcher fighters and Fairy IIID were on board, but Hawker Osprey aircraft superseded these in the 1930s.

In 1935 Fairey Seal torpedo bombers became the resident aircraft. However, a lack of hangar capacity proved critical during World War II when, in 1940, her air wing consisted of only 12 Fairy Swordfish aircraft, and these were at risk of attack. Another issue was an inadequate number of anti-aircraft guns, so overall Hermes only had light protection here as well.

At the start of World War II, when France fell, Hermes was at the forefront of blockading Dakar and trying to sink the Vichy French battleship Richelieu. However, despite one of her Swordfish aircraft scoring a direct hit, she failed to sink the French vessel.

Cruiser hull form

Hermes’ design incorporated a cruiser form of hull, with the main deck providing the ship’s strength. Hermes’ hangar was located above the main deck and the flight deck was above that. She was initially intended to operate both seaplanes and wheeled aircraft. However, operational feedback from the carriers HMS Eagle and HMS Argus’ early service with the Royal Navy meant this never happened. The revisions and changes, as well as the long time to completion, didn’t enhance her reputation with the Royal Navy, and she was deemed too small for major operations.

Hermes was assigned briefly to the Atlantic Fleet when she entered RN service in 1924 and, during her first months of service, she was involved in sea and flying trials. She participated in the 1924 Spithead Fleet Review, on 26th July, attended by King George V. In November 1924, after refit work, she was transferred to the Mediterranean Fleet and sailed for Malta.

Hermes arriving at Grand Harbour, Valetta in Malta.

Here, Hermes carried out further exercises with Eagle and other ships from the Fleet. She then had further refit work carried out in early 1925 before returning to Portsmouth. She sailed for the first time to the China Station in June 1925. Hermes spent most of her service career in the Mediterranean or at the China Station.

In 1927, Argus replaced Hermes on the China Station, allowing Hermes to return to England, and she was taken to Chatham Dockyard in November 1927 for refit. Some of her guns were changed, and she returned to the China Station in January 1928. During her time at the China Station, Hermes tended to operate during the summer at Weihai and at Hong Kong in the winter.

Hermes was assigned to the Mediterranean Fleet during the 1920s, before moving to the Far East in 1927, where she was mostly involved in trying to deter piracy.

During the 1930s, while still on the China Station, Hermes was involved in transporting Government ministers for talks with the Chinese government, as well as rescuing the crew of the submarine Poseidon. The carrier also assisted the Chinese government to survey the flooding in Hankow, Hubei Province. Other refits and operations followed including, in 1935, sailing to East Africa in response to the Italian invasion of Ethiopia.

Hermes returned to the UK in 1937 and took part in another Spithead Fleet Review, this time for King George VI. She was then placed in the Reserve Fleet before becoming a training ship at Devonport. Another refit was planned, but upgrades to her armaments and fuel capacity never took place, as the outbreak of World War II meant shipyard capacity was insufficient to accommodate her. Hermes was given a small refit instead and recommissioned in August 1939, taking 814 Squadron’s 12 Swordfish torpedo bombers.

At the start of World War II, Hermes briefly operated in the western approaches to combat the threat of German U-boats and E-boats. She was then transferred to the South Atlantic to work in conjunction with the French Fleet at Dakar. Again, her role was one of prevention, seeking out German shipping in the area.

Having rammed a merchant vessel during a storm in July 1940 while she was returning from her Richelieu engagement, Hermes was dispatched to Simon’s Town in South Africa for repairs, which took several months. On her return to service, Hermes was tasked with offensive patrols against German shipping in the South Atlantic, operating out of St Helena, and the search for the German heavy cruiser Admiral Scheer.

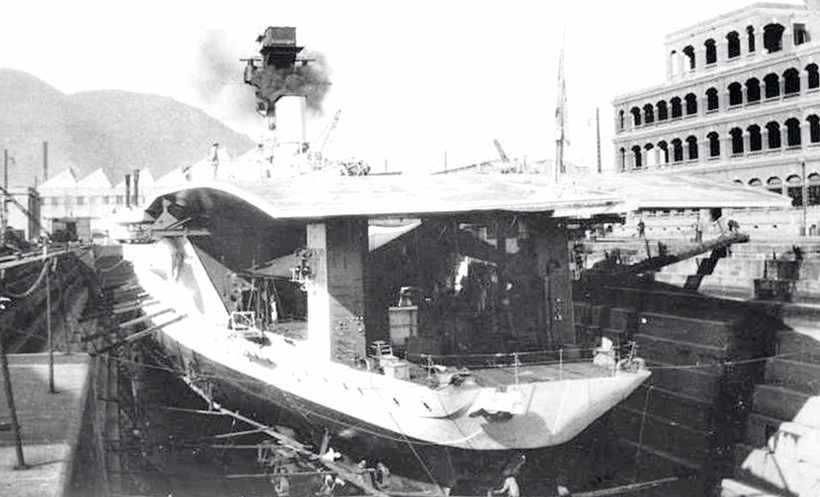

Hermes in dry dock in Hong Kong. Most of her service career was spent on China Station or with the Mediterranean Fleet.

East African campaign

Hermes also supported British and Commonwealth forces against the Italians in the East African campaign and later in the Anglo-Iraqi war in the Persian Gulf. Patrols resumed in the Indian Ocean before Hermes returned to South Africa for a further refit between November 1941 and February 1942. Once this was completed, she was assigned to the British Eastern Fleet at Ceylon. This fleet had been depleted by the losses of HMS Repulse and HMS Prince of Wales to Japanese naval aircraft.

On 9th April, 1942, Japanese aircraft from Admiral Nagumo’s carrier strike force launched an attack on the naval base at Trincomalee, Ceylon. Hermes wasn’t there, however, having had warning of the attack and sailed beforehand, heading south down the Ceylon coast. Crucially, though, she sailed without any of her aircraft and was in effect defenceless if she was later to be attacked by the Japanese aircraft. And that is exactly what happened, at around 10:35, when aircraft detected Hermes and an Australian Navy destroyer, HMAS Vampire. At least 32 aircraft attacked the ships, and sank Hermes when she was 45 miles north-west of Batticaloa.

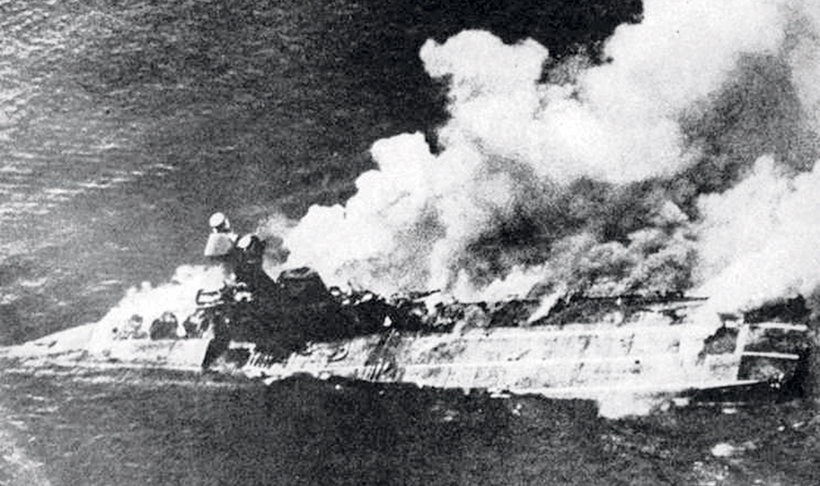

HMS Hermes sinking on 9th April, 1942.

Despite some RAF air support reaching the scene, they were too late and both ships were sunk by the Japanese. Of Hermes’ company, 307 were lost, along with nine from Vampire. The hospital ship Vita picked up survivors from both ships. The Japanese planes had further successes a couple of hours later, when the British oiler Athelstane and the corvette Hollyhock were also attacked and sunk in the Indian Ocean.

It took 60 years for the wreck of Hermes to be discovered by a local diver. Today, diving to see the wreck has become quite popular with local and international divers. In 2017, Royal Navy divers – in a joint dive with their Sri Lankan Navy counterparts – laid an RN Ensign on the wreck, which the divers found to be in good condition. After attempts to remove artefacts from the site, action was taken to prevent this, as the site is, like many other wreck sites, the final resting place of the crew who perished. Hermes was an innovative ship in her day, and contributed to the development of the aircraft carriers in later decades.

This feature comes from the latest issue of Ships Monthly, and you can get a money-saving subscription to this magazine simply by clicking HERE

Previous Post

Lakeshore Railroad celebrates 50th anniversary

Next Post

Stunning Vale of Belvoir Road Run