Classic, post-war liners

Posted by Chris Graham on 5th July 2020

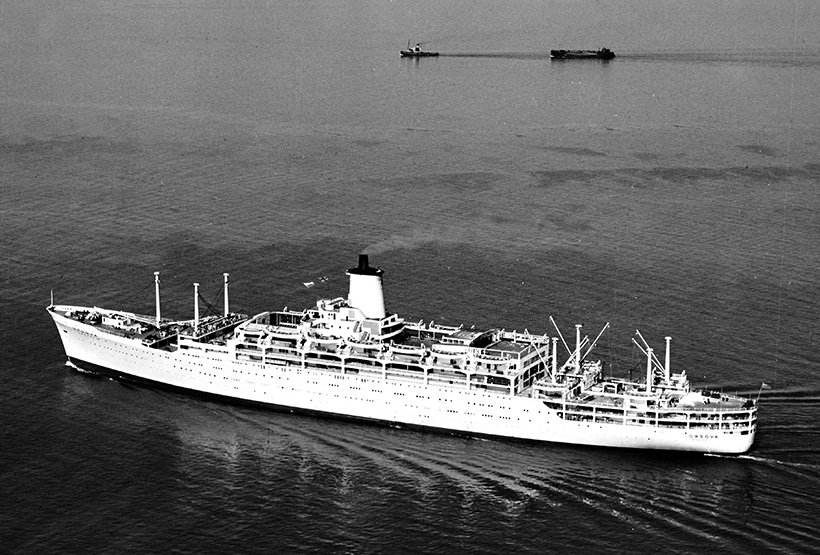

Orient Line’s Orsova was the last of a trio of 28,000grt classic liners built for the company during the post-war era. Stephen Payne recalls the ship’s design and career.

Classic, post-war liners: Orient Line advance promotional featuring SS Ossova.

Orcades was the first of Orient Line’s three, classic, post-war liners to enter service, in 1948, and she was followed by Oronsay in 1951, with the £6 million Orsova sailing on her maiden voyage from Tilbury to Sydney, Australia on 17 March 1954. Although the three ships are considered sisters, there were marked differences between them, with each being an improvement on its predecessor.

All three ships were built by Vickers Armstrong at Barrow but, whereas Orcades had some welding within her structure, this new technology was used on Oronsay to a much greater extent, while Orsova was constructed from prefabricated, fully-welded units weighing up to 50 tons. She was the first passenger ship to be fully welded.

Smooth operator

The absence of stepped, riveted plates made her hull smooth and streamlined, making her far more efficient through the water, due to the absence of drag-inducing eddies at the plate edges. As a consequence, on the same engine power (42,500shp), Orsova was the fastest of the trio, reaching 26.07 knots on trials, compared with Orcades’ 24.74 knots.

Orsova was the fastest of the three post-war sister, achieving 26.07 knots over the measured mile, in trials off the Isle of Arran.

Another advantage of welding was the saving of weight, because it eliminated rivets and the metal plate material needed for every overlap. Orsova was 14ft longer overall than her sisters, as she was built with a curved, rather than straight bow. The hull plating terminated at the forecastle, at the end of an extensive bulwark, rather than at deck level with railings, as on the earlier ships. The stern profile was also different, with the cruiser’s form being more upright, rather than canting marginally forward.

The three post-war sisters exhibited a similar profile, in that the wheelhouse and officers’ accommodation block was moved from the traditional position at the forward end of the superstructure, to abut the funnel, roughly midships. Orsova’s funnel was elegantly tapered rather than being vertical, as on her sisters, and the elevated surrounding structure was more compressed, to rationalise and improve the surrounding open passenger deck spaces.

Whereas Orcades had a tripod mast above her bridge, and Oronsay utilised a tear-drop sectioned pole mast, Orsova dispensed with a mast altogether; her radar scanner being supported by a platform at the forward end of her funnel, while her wireless aerial was strung between the funnel and a cargo derrick.

Orsova in the Thames Estuary, approaching Tilbury, on her maiden arrival.

Significant differences

As built, Orsova differed significantly from her sisters in that a ‘stove-pipe’ extension was added to the top of the funnel, to aid smoke dispersal. Deemed a success, similar appendages were added to the top of the funnels of Orcades and Oronsay, during their refits.

Orsova incorporated a number of technological improvements over her sisters. The four boilers on Orcades and Oronsay were replaced by three, larger units operating at a higher pressure, in Orsova. This minimised heat losses and improved the thermal efficiency of the plant, thus reducing fuel consumption. The internal outfit of the ship was improved by eliminating painted bulkheads; all bulkheads, including those in crew cabins, were faced with plastic laminate, which was easier to keep clean. All three ships were built with partial air-conditioning, but Orsova incorporated this to a greater extent than the others, including in a number of cabins and some public rooms.

Orsova’s sweeping bow allowed greater flare to be worked into the design, for improved sea-keeping.

The three sisters were combination, passenger-cargo ships. Two classes of passengers were carried – First and Tourist – as well as general and refrigerated cargo, and capacities across the three ships differed. The arrangement of the aft holds and hatchways was a factor in the disposition of the Tourist public rooms, which were positioned in the aft part of the ship.

Orcades’ and Oronsay’s Tourist public rooms were compromised by the hatch trunks and were rather sparse. In contrast, Orsova, with one hold less, had a much better arrangement. This included a stern-facing bar, which was a precursor to the later Oriana’s iconic stern gallery, and a Tourist Dining Room that wasn’t encumbered by a hatch trunk. While Orcades was converted to single-class configuration in 1964, and Oronsay became one-class as late as 1972, Orsova retained her dual-class configuration to the end.

Progressive looks

The last six Orient Line passenger ships were masterminded by Orient Line director, Sir Colin Anderson, and New Zealand interior architect, Brian O’Rorke. Anderson favoured modernism, and argued in the early 1930s that Orient Line should strike a progressive note to distinguish the Line’s ships from those of the traditionally-focused P&O Line. Anderson’s fellow Orient directors were persuaded, and charged him with implementing his vision.

Orsova arriving at Honolulu. (Pic: Stephen Berry)

O’Rorke was given the brief to design Orion so that passengers sailing half-way around the world over a period of five weeks, wouldn’t become bored with the interiors, and that they would feel cool in hot climes and warm in temperate regions. Simplicity and bold designs were the order of the day, and O’Rorke’s influence extended to crockery, cutlery and soft furnishings. It was the first time that such an approach had been taken, and it was a widely-acclaimed success.

Orion’s exterior was also distinctive, in that the black hulls of her predecessors were replaced by a corn-coloured hull, previously trialled for one voyage on Orama. Orsova was the last ship that O’Rorke single-handedly co-ordinated, as the later Oriana was worked on by a number of other architects, due to her size. As with previous Anderson/O’Rorke collaborations, Orsova was given a corn-coloured hull, and was outfitted very much in the modernistic mould.

Orsova’s Tourist Class Tavern.

High safety standards

Orsova was laid down early in 1952, and was launched at noon on May 14th, 1953, by Lady Anderson, wife of Sir Colin Anderson. Orsova was designed and built to meet the requirements of the inter-governmental Conference for Safety of Life at Sea 1948 (SOLAS 1948), whereas Orcades and Oronsay were built under SOLAS 1929 regulations.

The new requirements were embedded in the UK Ministry of Transport regulations, and set higher standards for many aspects of the ship, including its structure, subdivision, pumping, electrical installations, fire protection, life-saving, navigational aids, personnel and operations. This resulted in an increase in the number of fire-screen-insulated bulkheads.

Orsova arrives at Circular Quay, in Sydney, Australia, during the late 1960s. (Pic: Stephen Berry)

Unlike her sisters, Orsova was fitted at build with a pair of Denny-Brown stabilisers, mounted below the waterline forward of the generator room on the tank top. When deployed, the fins reduced a roll of 20°, greatly aiding passenger comfort.

Orsova followed the familiar pattern of extended line voyages to Australia and beyond into the Pacific, punctuated by seasonal cruises. In 1960, P&O and Orient Line merged to become P&O-Orient Lines and, by 1964, Orsova had her corn-coloured hull replaced with P&O white.

In November 1972, during a cruise from Southampton, over 300 persons on board went down with dysentery. When the ship returned to Southampton, 212 crew were dismissed after they refused to undergo medical tests to find the source of the disease.

The First Class Library on SS Orsova.

Extensive refit

Following an extensive, three-week, £250,000 refit at Southampton, the ship departed on December 17th, 1972, on her Christmas cruise. However, she was so short-staffed due to the crew dismissals, that passenger numbers had to be restricted to 650 – all First class – and many passengers had their holiday cruise cancelled. But, with conditions being so bad, passengers were given refunds, reducing further P&O’s already depressed earnings on passenger ship operations for 1972-73. Orsova’s refit was intended to make her more attractive as a full-time cruise ship, but the two-class demarcation was retained.

On January 9th, 1973, Orsova left Southampton on a voyage to Australia, via the Panama Canal. During the summer of 1973, P&O announced that Canberra, which had just had a disastrous cruise season out of New York and had been laid up, would be withdrawn, and that her 1974 cruise season – including a World Cruise – would be operated by Orsova.

However, a few weeks later, it was announced that Canberra was going to be retained, and Orsova would be withdrawn instead. An upsurge in the demand for UK cruising had been detected, and it was felt that Canberra – already operating as a one-class ship – would be more suitable.

The cost of converting Orsova into a one-class ship was one of the deciding factors, but the ship would also have required some structural renewals, and the cost of this may have also been a factor. All three of the post-war trio of 28,000grt ships suffered from tank-top corrosion.

Orsova’s last cruise season was a series of voyages from Southampton, culminating in an extended, Caribbean cruise in November 1973. Apart from the melancholy of the final voyage, and the flying of the ship’s paying-off pennant at each port of call, a fracas between two crew members led to one being stabbed during the return Atlantic crossing, as the ship headed for Madeira from Barbados.

Orsova was a particularly fine ship, and certainly the most refined of the Orient Line post-1945 trio.

The master ordered all possible speed to reach the island as quickly as possible to get the injured crewman to hospital, but he sadly died of his wounds before arrival. The culprit was detained on the island and collected by British police who flew out to extradite him, and Orsova arrived back at Southampton on November 25th, 1973.

After destoring, Orsova departed for Kaohsiung on December 14th, 1973, sailing via Cape Town, and arriving at the shipbreakers on February 14th, 1974, with an official hand-over the following day. Orsova was laid-up, and soon seen canted to port and trimming heavily by the stern, to aid the removal of her remaining fuel oil. After stripping out her interiors, Nan Feng Steel Enterprise Company began the demolition of Orsova on December 17th, 1974, with work completed in early 1975.

Orsova was a particularly fine ship, and certainly the most refined of the Orient Line post-1945 trio of 28,000grt new-buildings. She would, in time, be the starting point for the design of the last and greatest of the Orient Line ships, Oriana. Retaining her two-class configuration to the end, her Tourist class public spaces and open deck arrangements were a great improvement over her siblings, through optimising the design. Regrettably, at less than 20 years of service, she had the shortest career of the three sisters; a victim of circumstances and the steep rise in fuel prices that ended the careers of many fine ships in the first half of the 1970s.

For a money-saving subscription to Ships Monthly magazine, simply click here