Precision crop drilling in Scotland

Posted by Chris Graham on 23rd May 2020

Pete Small take a nostalgic look back at precision crop drilling in Scotland down the years

Precision crop drilling in Scotland: Drilling sugar beet at Kirkton of Balmirmer in Angus, in 1956, using the famous Stanhay drill that could sow fodder root crops, too.

Once the potato crop was planted, many farmers breathed a sigh of relief although, for others, there was still more work to do. Those running mixed farming systems still had to get their fodder root crops sown, and perhaps re-seed or undersow some grass. Factoring-in the times when sugar beet was grown in Scotland, and the replacement crops of vining peas, beans and field-scale vegetables, gives an idea of how busy spring could be.

Throughout April and into May, all of the other tasks – such as top-dressing and spraying – went on alongside caring for breeding and feeding sheep and cattle. There was often a bit of a tidy-up too, once potato planting was completed, with any big stones left by stone separators gathered from headlands and compacted, or rough areas being cultivated to tidy them up. The chance was also taken to tidy up all the empty seed and fertiliser bags.

Those who kept breeding sheep liked to grow a few mangolds for feeding after New Year. These tended to be sown in late April, before the turnip crop. Time was taken to get them sown, even if other jobs were going on. On easy-worked soils, one man could often work on his own to get some artificial fertiliser broadcast, then work it in to get a seedbed made with similar deep-cultivation equipment as that used for the potato crop. Much of the artificial fertiliser contained Boron, to prevent some of the rots that could occur later in the season.

The soil for fodder root crops often had a coating of manure applied before ploughing, which was done a bit deeper than for cereals. Once again, the rotavator came into its own by making the fine seedbed needed; the seeds were so small that they needed a very fine tilth to hold them at the correct depth, and to maintain moisture around them. Later, the Lely Roterra, Howard Harrovator and Maschio power harrows proved popular for these types of seedbeds.

Many farmers liked to grow their root crops on ridges so, once the soil had been broken down the drill plough, from horse-drawn types through to the likes of David Brown, Ferguson, Fisher Humphries or Ransomes mounted versions, would draw the drills as straight as possible. These drills tended to be shallower and flatter than the potato ridges, as the seed was sown on top of them.

This David Brown ridger is fitted with longer-than-standard mouldboards, which would make it easier to create the shallower ridges needed for root crops.

Before the days of powered cultivators, any drills made that were still loose and cloddy, were rolled with a specialist drill roller. This had a conical-shaped barrel that straddled the drill and pressed it firm. The rings on the roller were wavy, or toothed, or even ‘nicket’, as they say in Scotland, so any clods were crushed down further. The consolidation action was vital so that the drills didn’t dry out after sowing, which was particularly noticeable in lighter soils.

These rollers had been left over from the horse age, when rolling, sowing and the later scarifying operations, were done in pairs. Later, drawbars were fitted to the old horse rollers and, later still, ‘A’ frames for using on the tractor’s linkage. Sometimes they remained as a two-drill machine and, in some cases, two old horse rollers were made into a four-roller, tractor-mounted machine.

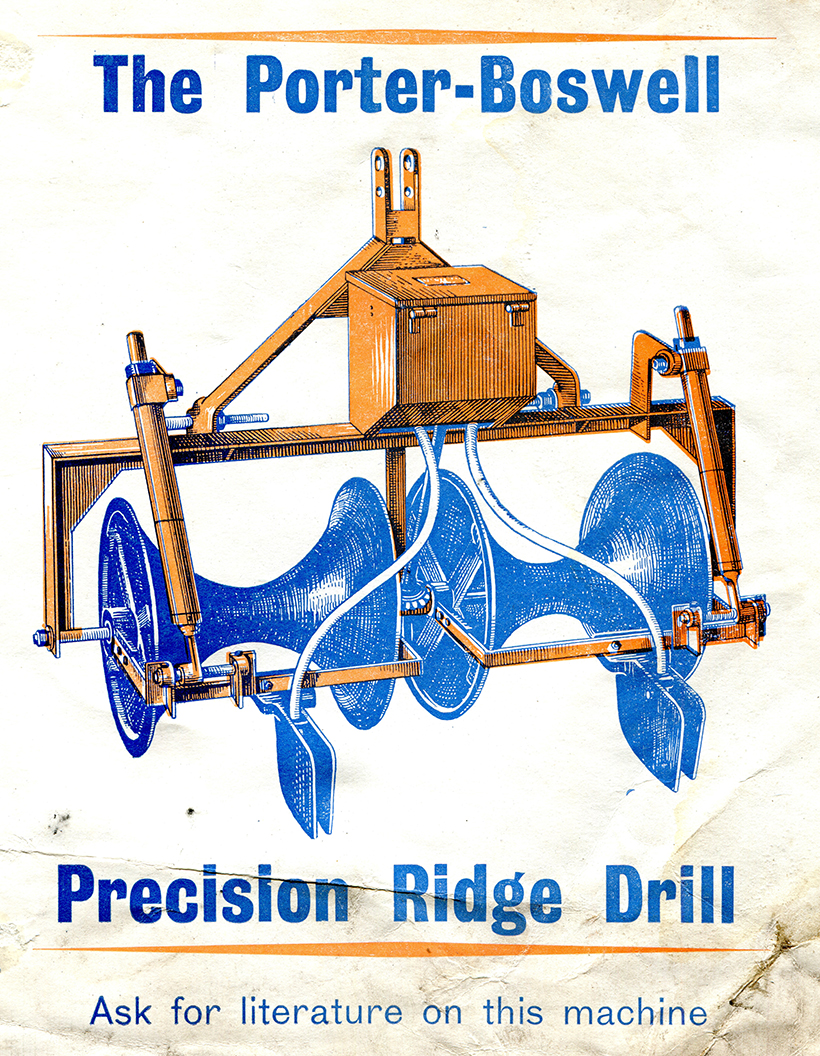

An image of the Precision Ridge Drill marketed by Porter Boswell, of Carlisle.

Makes of these rollers included Elder of Berwick, Ballach of Edinburgh and Hunter of Maybole. When chemical weed control arrived, some practised a stale seedbed system, where cultivating and seedbed creation was done in advance of sowing, and left to green-over with weeds, before being sprayed with Paraquat to kill them off before the sowing operation. This applied to the other root crops including yellow turnips, swedes and kale.

Yellow turnips would be sown first to get them to full size by late autumn, as they weren’t winter-hardy, so were pulled early for feeding to dairy stock; although they could also be sown later, without too much reduction in yield.

Hardy crop

The swede turnips were winter-hardy, and could sustain frosty weather and be pulled or grazed in situ throughout these months. By early May, it was time to sow this swede crop, with care taken to avoid any late frosts that could force a re-sowing operation, as it was frost that would lead to bolting of the crop. The sowing was often done in stages if the crops were to be hand-hoed, giving time to keep on top of this slow and laborious task, and not let the young plants get too big before they were thinned-out.

A former horse-drawn turnip barrow converted to tractor use. Note the handles at the rear.

In horse-drawn times, the two-row turnip drill was used, with a range of manufacturers big and small, including Wallace of Glasgow, Sellars of Huntly, Steele of Dundee and Pierce of Wexford. Again, they were two-row affairs, usually with two, smooth and concave rollers sitting on the drills, and two small, metal seed boxes on top. From these, two metal tubes dropped down to a small, ‘V’ share that made an opening on the ridge for the seed to drop in. Following up were two flat rollers that pressed soil over the seed. A little brush on a shaft, turned by the front rollers, acted as an agitator – pushing the seed down the tube.

Apart from being able to open or close the orifice from which the seeds exited, there was no metering of the seed and, when germinated, the crop resembled tiny hedges that needed thinning-out by hand. These early drills were converted to tractor use before more refined machines came along. Also, attachments to make old drills into more accurate machines regarding spacing and seed rates, came from firms such as Porter Engineering Co Ltd, of Carlisle, which produced the McCubbing Precision Seeder.

Some of these refined drills included the ‘Bean’ drill from Humberside Agricultural Products, Planet, and Russell of Kirkbymoorside. The arrival of precision drills, from the likes of Stanhay and Webb, were the big game-changers; seed could now be placed at specific intervals, making further operations easier and saving on the amount of seed used overall. They used holed belts or wheels of varying sizes and spacings to collect one of several seed types at a time from the seed box.

A typical, four-row Stanhay drill of the type that sowed many a turnip crop, behind an International B-275.

The seed was dropped at the correct spot before being pressed in by a covering wheel, while a front wheel smoothed the track and provided drive to the feed mechanism. Many growers stuck with a two-row drill, but others moved out to four rows. Massey Ferguson also offered a precision drill for a short period. These could be fitted with concave rollers for those still growing on drills, while some drills were fitted with larger, pneumatic-drive wheels to help in soft, peaty or sandy soils.

Root crops usually meant 26in-wide drills, as opposed to the 28 inches needed for potatoes, which meant the ridgers had to be changed for the job. Some growers went in as narrow as 24 inches, which resulted in adjustments to the tractor wheels and, in some cases, row-crop wheels were added to get the tractor narrow enough.

Keeping straight was paramount. Ridges were easier to negotiate if they’d been drawn straight. Sowing on the flat, which eventually became more popular, was trickier. The drills were equipped with markers so the row widths could be kept consistent after each pass. The driver had to swing these markers over to the other side at each end of the field, as well as check that the wheels or belts in the seed boxes were still discharging the seed correctly.

Some used long markers to reach the centre of the tractor, but most used markers for the front wheels to follow. Concentration was required to keep to the marks, as any deviation resulting in kinks in the drill led to sarcastic comments about how the hares were going to skin their shoulders while running up and down a ‘squint’ drill of fully-formed turnips!

Many of these operations were required for the sowing of sugar beet, which was grown in Scotland from 1926 to 1971 – although an earlier start often occurred. Sometimes greater care was taken to get a really flat seedbed, with levelling harrows used from the likes of Blench and Cousins.

Replacing beet

When the sugar beet factory at Cupar, in Fife, closed in early 1972, some farmers replaced sugar beet with vining peas and beans. Using grain drills, some of the vining co-operatives sowed their own acreages, or the farmers letting out their land sowed the crop under the instructions from the group. This sometimes resulted in having to interrupt other jobs during spring, to get the sowing carried out within the schedule.

A transplanter at work putting in lettuce – one of the many vegetables that replaced the sugar beet crop in east-central Scotland.

Field-scale vegetables have been another successful replacement for sugar beet, with many different types grown. Some are transplanted into the prepared soil by specialist machines, while others – such as carrots and parsnips – are sown by modern precision drills, often arranged to sow in a bed format prepared by using bed tillers and even stone separators. These new drills have been refined to carry out all of the different requirements of the various crops, with additional equipment, such as the Horstine applicator, fitted for pesticide application.

Sowing carrots on a bed with a five-row Stanhay drill with pesticide applicators on top, operated by a Renault tractor.

While all this is going on, the cereal crops were germinating. Farm folk got nervous, as the neighbourhood could see if it has been sown straight and looked for missed bits because of choked spouts on the seed drill – both ‘criminal offences’ within the farming community!

Potato grading of some of the good keeping varieties, being marketed late for human consumption, was still being done and being sent to dress tatties instead of being out in the fields was purgatory for any young operative.

Time was also taken to undersow grass seed into a nurse crop of spring barley or oats, once these crops were through the ground and strong enough. Great care was taken when ordering the seed and often the seed merchant’s help was involved to choose the right mixture for the differing soil types, the number of years the crop would be down for and the end use of the crop – be it grazing, hay or silage. Sowing rates would be in pounds-per-acre, and different mixtures varied in their bulk so grass could come in a variety of sack sizes.

The JEC Sod-Seeder was another of the machines developed for both grass re-seeding and for direct-drilling root crops as a catch crop.

The field was measured, headlands sectioned-off and the seed bags placed evenly to help assess the seeding rates. Because the seed was sown at pounds-per-acre, as opposed to hundredweight-per-acre for grain, getting the seed rates accurate was very important. If the grass seed barrow ran out of seed before it reached the second bag, then it needed shutting down – hopefully not too much, otherwise there will be a thick cover of grass in one section and thinner cover in the rest. Likewise, there might still be seed in the seed boxes, so the rate had to be opened-up – but at least if there was some left you could go over the area again at the end.

Many differing ways could be used to sow the grass seed, including hand-sowing – which was still being done long after the drill had become the norm for the grain crop. Old hands would sow from a sheet or seed lip tied around their waist, or seed fiddles – such as the Aero type – were popular until relatively recently.

Barrow’s best

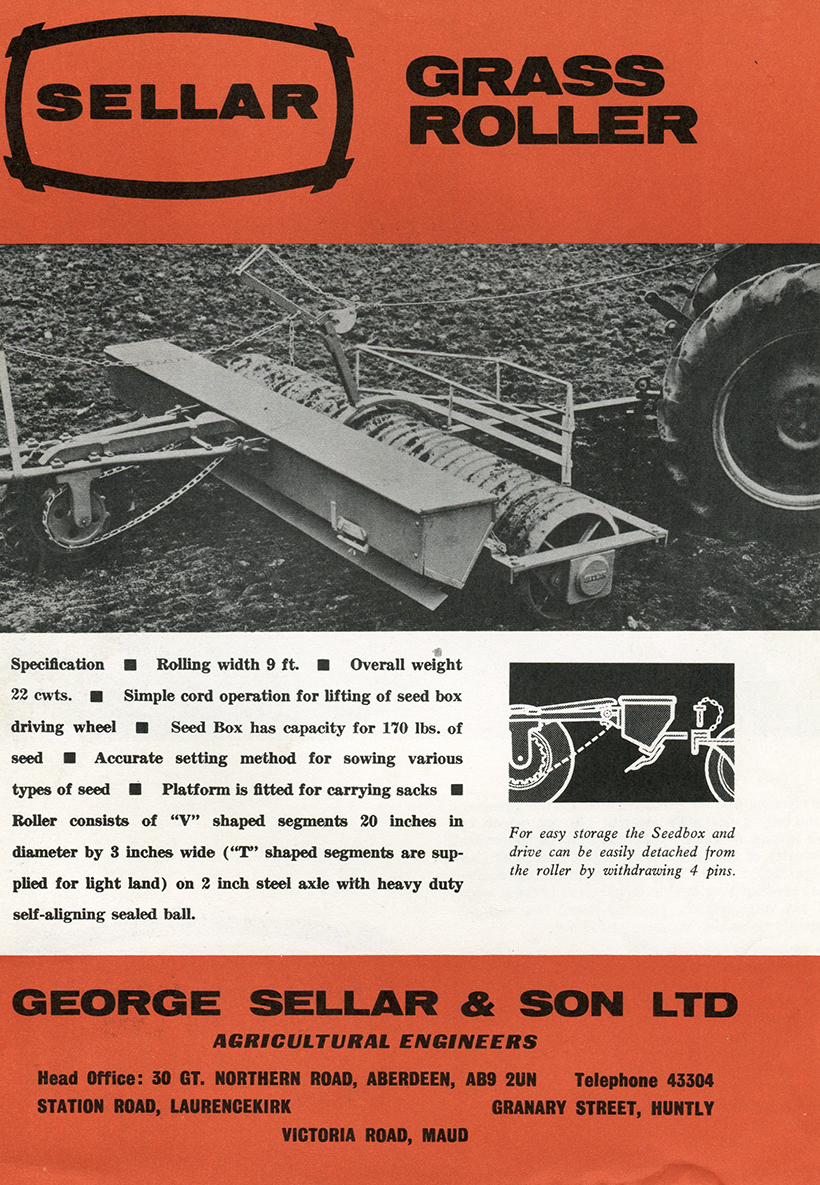

For many farms, though, it was the grass seed barrow that prevailed. In England especially, the barrow could be pushed by hand, and was often known as a ‘shandy barrow’. In Scotland, several companies firstly marketed horse-drawn types, followed by tractor-drawn and eventually fully-mounted types. Some of the most well-known marques were Elder of Berwick, Sheriff of Dunbar, Garvie of Aberdeen and Sellar of Huntly.

Undersowing grass seed into a crop of oats in the 1980s, with a Sellar of Huntly grass seed barrow behind a John Deere 3040.

These barrows had a working width of 18 feet, and could be folded round for transport. The seed boxes were made of wood and sat upon a frame. Inside the boxes was a shaft of star wheels above the seed openings, which were opened or closed by a handle at the back. These wheels forced the seed out of the holes, from where it fell to the ground.

The star wheels were driven by the land wheel(s) and, as the boxes were swung round into position, care had to be taken that each box went into the correct sockets – with a pin holding them in place. There was a small handle for engaging the drive, while marker weights were dragged from the outer ends.

To incorporate and cover the seed, several methods were used. Sometimes, in cloddy soil, only a pass with a roll was needed, but, more often than not, it was a set of grass seed harrows that were used. These were a much lighter version of the ordinary drag harrows used for grain. Some farmers even used a Ferguson weeder to cover the seed without damaging the young cereal plants and, because it was important not to bury the grass seed too deep, some even dragged twigs and saplings over the soil before the final roll.

This was a broadcast method but, as time went on, some went on to use the grain drill to sow grass seed straight into the soil, with Fiona, Bamlett Tive and the Ransomes Nordsten drill with Suffolk coulters being favoured. Some could sow the small seeds out of the normal grain boxes, while others had a special, small grass seed box adaption fitted – such as the Massey Ferguson 30 and the Hestair Bettinson. Many drills had spring tines fitted to cover the seed prior to rolling. This type of sowing saw the grass seed sown alongside the grain crop.

A view of the grass seed box that was an accessory for the Massey Ferguson 30 combine drill.

Today, the modern pneumatic-type drills, often used in a one-pass format, are popular for sowing grass, as are re-seeding spring-tine harrows such as those from Einbock. Some specialist drills, such as the Moore Uni-drill and Howard Rotacaster, were also part of the armoury, but were most likely to be used in reseeding operations to improve old pasture or hill grazing.

Machines, such as this Moore Uni-drill, were often used to re-seed grass.

The Howard Rotacaster was another machine that could be used to great effect with re-seeding pasture or undulating ground.

One of the issues of drilling grass into straight lines was inadequate coverage, and some halved the seed rate and crossed drilled at right angles to give greater coverage of seed. In very dry weather, drilled grass can show up the lines of plants, leading to a poorer sward. Many still stuck by broadcasting seed by the old grass seed barrow, as it gave fuller plant coverage.

A final roll was all that was needed to complete the job and the likes of Sellars of Huntly actually mounted a grass seed barrow on a roller, to do the job in one operation.

With any leftover stones cleared, plenty of tidying up carried out and machinery prepared for storage, the spring work was done, but plenty of work still needed doing on the mixed farms of the area.

The Sellar Grass roller combined operations.

To subscribe to Tractor & Machinery magazine, simply click here