Unique 1917 Bucyrus Class 24 steam dragline saved

Posted by Chris Graham on 28th July 2023

Keith Haddock recounts his involvement in the rescuing, moving and restoring a unique, 1917 Bucyrus Class 24 steam dragline.

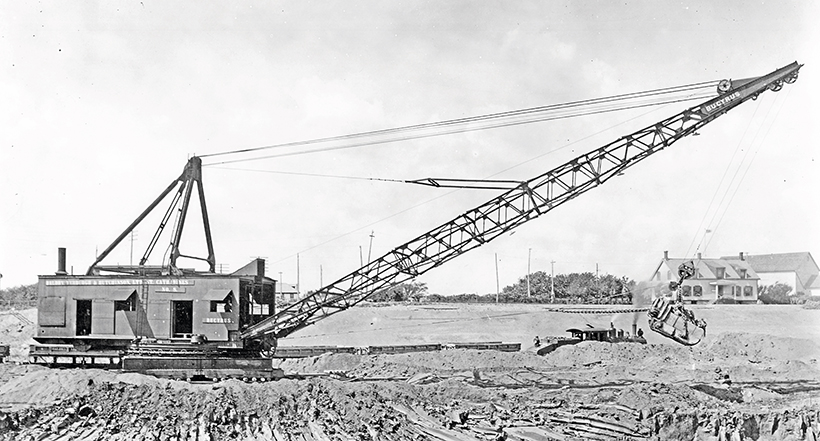

A typical Bucyrus Class 24 dragline was mounted on skids and rollers and carried a 3½ cubic yard bucket.

Claimed as the world’s oldest dragline in complete condition, the Bucyrus Class 24 steam dragline is on display at the world-class Reynolds Alberta Museum, Wetaskiwin, Alberta, Canada. After being submerged for three decades in a water-filled coal pit near Edson, Alberta, this machine was rescued and moved to its new home in July, 1998. After a two-year restoration project sponsored jointly by the Edmonton branch of the Canadian Institute of Mining, Metallurgy & Petroleum (CIM), the national Coal Division of the CIM, Bucyrus International, Inc. and private donations, the machine was ready for permanent display, although not in working order.

Showing the Class 24 dragline in operation at Coal Valley Mine before operations shut down in 1957. It excavated coal and loaded it into rail wagons.

The dragline, known as a Bucyrus Class 24, was found in an area known as the Coal Branch of Alberta, an area extensively mined by surface (opencast) methods going back to the early 1910s. Some of these operations were massive, going down hundreds of feet with the largest steam excavators available. Private companies ran the operations, and also built and owned the towns in the area, some housing as many as 4,000 people. As the coal markets softened in the 1950s, the mining operations closed one by one, and people migrated from the area leaving the towns deserted. A major reason for the decline was the changeover by the railways from steam (a large market for coal) to diesel. By 1960, all the mines had completely shut down.

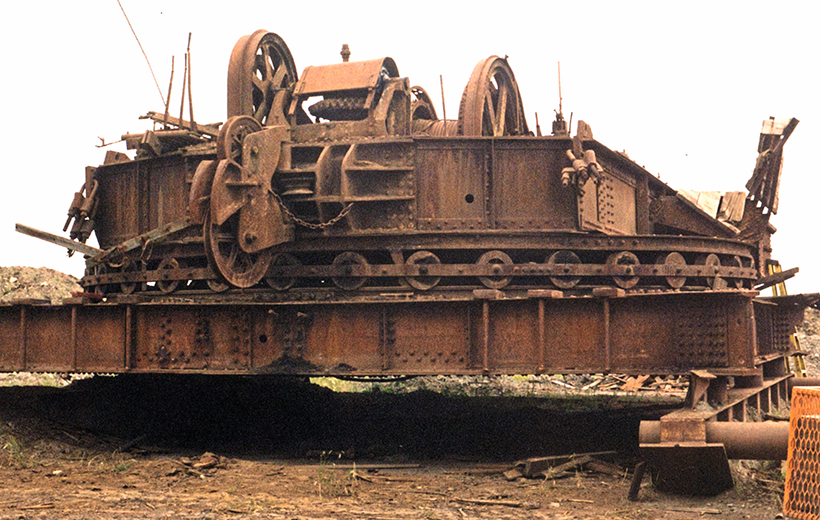

The Bucyrus Class 24 dragline at Coal Valley as it appeared after being submerged for over three decades.

The resurgence of coal markets in the late 1960s prompted companies to return to the Coal Branch. Surface coal mines gradually started up again, this time with modern equipment. One of these was the Coal Valley Mine, a property purchased by Luscar Ltd. and put back in operation in 1978. I was directly involved with this operation and, during my time as Engineering Manager in the early 1980s, it was known that an old dragline still existed in one of the water-filled pits left from the earlier operation. Nothing could be seen above the water level, and no-one knew exactly what the machine was. We even sent down a team of amateur divers who did locate the dragline but could not find a name plate to identify the model.

During its three-decade-long underwater experience, the Class 24 dragline’s boom collapsed and buckled under impact. Note the heavy wooden skids under the machine.

By 1987, Luscar’s Coal Valley new mining operation was approaching the submerged dragline pit, so in order to continue mining coal from the same area, the pit had to be pumped out. After months of pumping, the dragline once again stood high and dry, but three decades under water had felled its boom. Excitement mounted as I climbed on board for the first time and read the cast iron plate: ‘Class 24 Bucyrus Drag Line Excavator No. 874.’ This was indeed a valuable find, a steam-powered machine built in 1917. Only one other Class 24 was known to exist and that machine, at Monroe, Louisiana, has since been scrapped.

House removed ready for transportation, revealing the steam engines to power the hoist and drag drums.

Machine description

The Bucyrus Company produced the Class 24 Dragline Excavator from 1911 to 1929. It was available with steam or electric power and could be purchased for rail mounting or on skids and rollers. The Coal Valley machine is of the latter type, and that’s what makes it particularly interesting. Skids and rollers were a method of moving the very earliest machines, and it pre-dates rail-mounted, crawler-mounted and walking draglines. The mounting has no propelling drive whatsoever, so moving the machine was a skilful and sometimes tricky operation.

The steam-powered draw works of the Bucyrus Class 24 dragline.

Sitting on rollers placed on heavy timbers, the machine pulled itself along the ground using its bucket and drag rope. The separate rollers were manhandled by the ground crew who carried them from the rear to the front of the machine as it moved ahead (or backwards). The steam powered machine had a main steam engine for both hoist and drag drums which operated through steam clutches and brakes, and a second steam engine for the swing. The Class 24 was the largest of the Bucyrus ‘Class-series’ draglines whose model nomenclature indicated the roller turntable diameter. Thus the Class 24 turntable measured 24 feet in diameter. The Coal Valley machine was equipped with a standard 100-foot boom carrying a 3½-yard bucket. The house was built entirely of wood. The large horizontal boiler and water tank are mounted at the rear of the revolving frame and, according to the specification sheet, working weight was 145 tons.

Ready for transportation, the base, roller circle and revolving frame will make a 25-foot wide load!

Mine description

The machine at Coal Valley arrived second-hand in 1927 and worked until about 1957 when the mine closed. With pumping discontinued, the pit soon filled with water. The old dragline worked at the bottom of the pit which had been excavated by shovels to the dragline’s working elevation, some 200 to 400 feet below ground level. The coal formation was in a giant syncline with coal over 50 feet thick in some places. So from its position, the dragline excavated coal from up to 100 feet below its level, and loaded into rail cars hauled by steam locomotives.

After being hauled to safety from the active pit at Coal Valley, the boom, gantry, boiler, water tank and house have already been removed. The Premay trailer is skidded under the base in readiness for the move to Wetaskiwin.

It’s interesting to note that the ‘modern’ mining sequence employed by Luscar was exactly the same as that employed by the old-timers, except coal was excavated by an electrically-powered Marion 7450 walking dragline, specified by me, with 14-yard bucket and 200 feet of boom. Diesel-electric dump trucks provided the haulage. The Marion 7450 started operation in 1980 and performed exactly as specified until 2016 when new pit areas were opened and the dragline was scrapped a few years later. Today the mine is still in operation but hydraulic excavators and dump trucks handle most of the excavation.

The Premay 64-wheel trailer, with its 25-foot wide load, is ready for the road. Five other loads carrying the boiler, boom and other components completed the dragline move.

Machine restoration

When Luscar recognised its importance, the old machine was dragged to a safe distance from the mining operations, and lobbying commenced for its preservation. Several groups expressed an interest but nothing definite developed until six years later when the CIM finally secured the machine’s preservation. The Edmonton Branch chose the dragline’s preservation as their centennial project. It took a lot of money, time and organisation, but fund-raising activities of the CIM’s Dragline Committee, generous donations of cash and time, plus government grants came in after much publicity. Special thanks were given to local haulage contractor Premay for donating the entire cost of loading and moving the machine! The total project cost $250,000, about half of this in the form of ‘work-in-kind’ materials and contractors’ donated time.

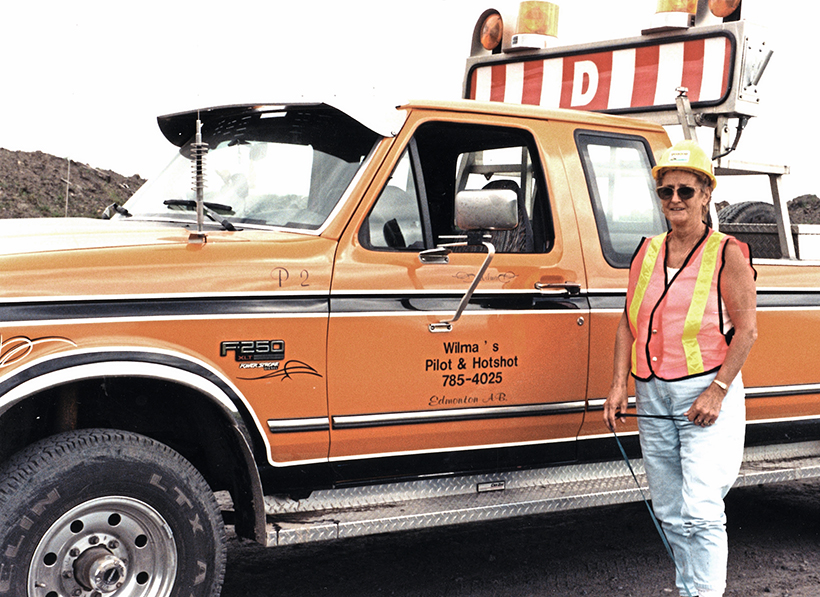

Wilma’s Pilot and Hotshot was in charge of piloting the load.

In readiness for the relocation at Wetaskiwin, some 250 miles distant, crews cleaned and dismantled the ancient machine. A specialised contractor removed and disposed of asbestos shrouding the old boiler. Abnormal load specialist, Premay of Edmonton, undertook the three-day journey in July 1998 to move the machine. Skilful crews jacked the upper and lower frames, in one piece, onto a special 64-wheel trailer to make a load 25 feet wide. The boom, boiler, gantry and miscellaneous hardware made five additional semi-trailer loads. At the museum site the machine was gently manoeuvred along a new access road, then lowered onto a specially-prepared concrete base.

En-route by 64-wheel trailer to its new home in Wetaskiwin, the world’s oldest dragline certainly drew lots of attention from passing motorists. The 250-mile journey took three days, including loading and unloading.

Following laboratory testing, the museum specialists deemed that none of the original wooden house was salvageable. So, after removing all the hardware and original frame for re-use, a new house was built by skilled carpenters at the museum. They also constructed a complete new set of wooden skids, wooden roller path, and procured new rollers on which to mount the machine. Several local contractors donated time and materials, including replacing worn-out or missing parts. Amazingly, Bucyrus International was able to provide a set of original drawings for the Class 24 which proved indispensable during the restoration phase.

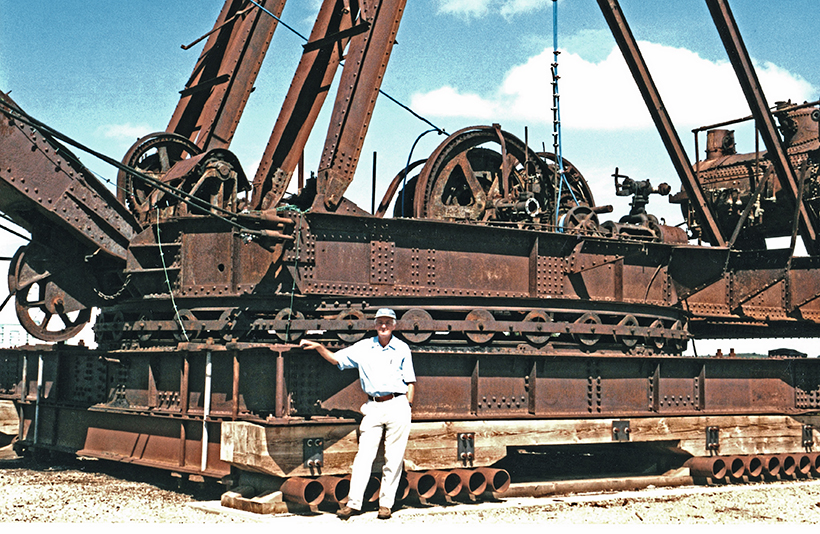

Keith Haddock standing against the dragline during erection at Wetaskiwin. The draw works and rear boiler are exposed until the new wooden house is constructed.

At last, on a glorious sunny day in September 2001, more than 200 guests attended a dedication ceremony to formally hand over the dragline to the Reynolds Alberta Museum and commemorate the CIM’s centennial anniversary. This event celebrated the culmination of four years’ hard work by the CIM’s Dragline Committee, museum staff, contractors, and volunteers involved in the project.

This Class 24 dragline propelled on skids and rollers. Here, a reinforced concrete base has been laid, and the new steel rollers and hardwood timbers fixed to the machine above them can be seen.

The Reynolds Alberta Museum at Wetaskiwin, Alberta, Canada is a world-class facility where over 1000 antique vehicles and equipment from agriculture, industry and transportation are on show or in various stages of restoration. The fully-restored vehicles are in immaculate condition, and displayed in superb settings. Although antique cars and agricultural exhibits dominate, the collection does include a large number of construction and surface mining machines.

Originally built in 1917, the world’s oldest remaining dragline now sits on permanent display at the Reynolds Alberta Museum. Note the wooden coal hoist and bunker.

The dragline is not a working exhibit, but its outer appearance with a freshly-painted house gives visitors the impression that the machine just left the factory! Inside the house, visitors can walk back in time to steam power technology of a bygone age. They can marvel at the array of steel pipes, heavy gearing, steam clutches, winding drums, and giant steam boiler. The dragline now sits proudly in its new permanent position where it will fascinate visitors for decades to come – Old Glory indeed!

Fully assembled, the Bucyrus Class 24 dragline with 3½-yard bucket proudly stands as the largest exhibit at Reynolds Alberta Museum at Wetaskiwin, in Alberta, Canada.

A complete new wooden house and hardwood skids were installed on the restored dragline.

This feature comes from the latest issue Old Glory, and you can get a money-saving subscription to this magazine simply by clicking HERE