More steam shovel history

Posted by Chris Graham on 20th March 2021

Keith Haddock delivers another bucketful of steam shovel history as he continues his A-to-Z review of notable American manufacturers.

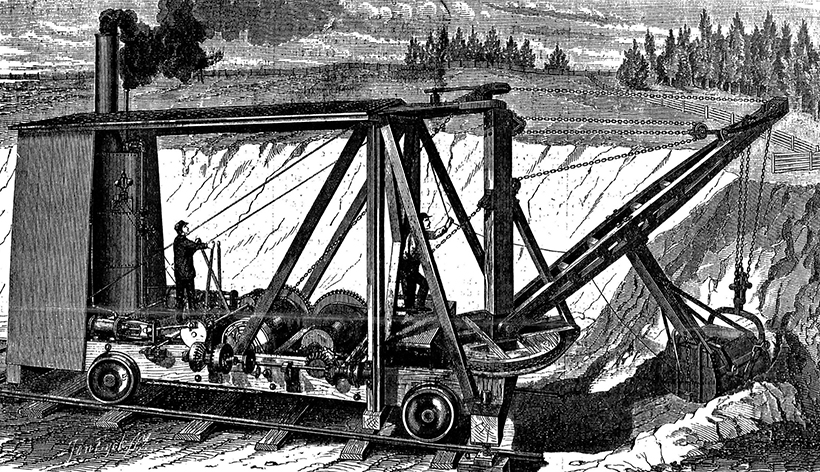

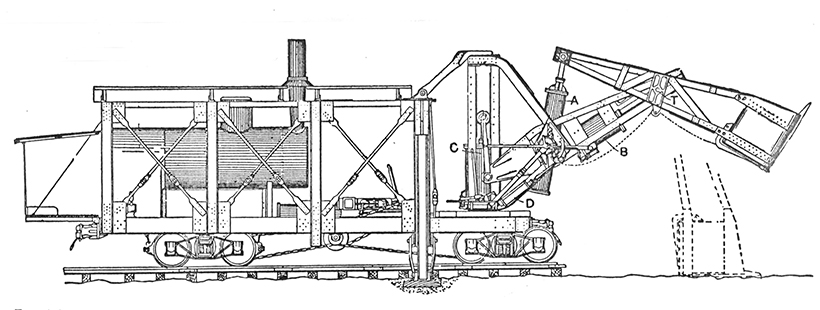

Steam shovel history: This is the Oswego Boom Machine designed and patented by Sage & Alger in 1870. Notice lots of wood construction and, unlike most other steam shovels, it featured a luffing boom.

OSWEGO

Patented in 1870, the Sage & Alger shovel – designed by Clinton H Sage and Samuel B Alger, and known as the ‘Oswego Boom Machine’ – was initially built by John King & Co of Oswego, New York. According to literature dated 1885, this location underwent a name change, to Kingsford Foundry & Machine Works at this time. It also appears that Oswego machines were built by the Vulcan Iron Works of Oswego, New York, which was owned by the same, John King. This was probably the same factory in Oswego, and shouldn’t be confused with the Vulcan Iron Works of Toledo in Ohio, where steam shovels were also built.

The first Oswego shovel was of the luffing-type, with a dipper arm attached and hinged to the boom, close to its centre. This was similar to many small, rope-operated excavators of later years, where raising or lowering the boom provided the crowding action. The Oswego shovel was advertised as built ‘in first class manner’, with framework in white Canadian oak, all gearing of cast steel, double hoist engines with 8x12in cylinders, and boiler of upright design, large enough to ‘furnish an abundance of steam.’ The clutches were known as ‘Alger’s Expansive Friction’-types, which were said to take hold of the load gradually, and ‘thus obviate the danger of breakage incident to the use of a positive clutch.’

Another Oswego shovel was known as the ‘Improved Land Excavator’, and was similar to the first, but with numerous improvements, including a crowd mechanism worked by rack and pinions. The vertical boiler on this machine was 54 inches in diameter and 8ft 6in high. Shipping weight was estimated at 48 tons. After about 1885, very little is reported about Oswego shovels, except that the Vulcan Iron Works factory was destroyed by fire in 1886, and it’s assumed the company went out of business around that time.

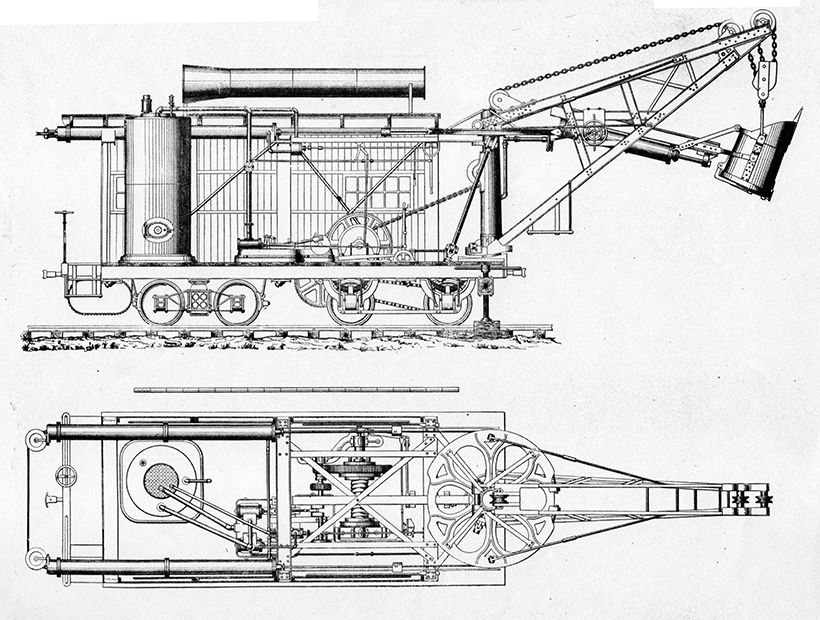

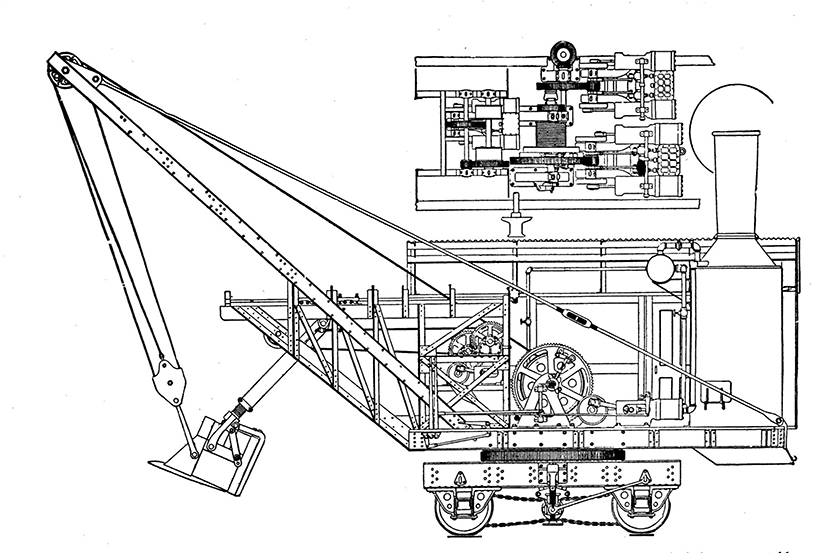

A drawing of Dill’s Steam Shovel and Derrick Car of 1881, as built by Industrial Works of Bay City, Michigan.

INDUSTRIAL WORKS

In 1873, the Industrial Works company of Bay City, Michigan, was established to manufacture special equipment for mill, marine and railroad use. Its first involvement with excavators was in 1881, when it began manufacturing Dill’s Steam Shovel and Derrick Car. This shovel was also known as the Clement Steam Shovel, so named after William L Clements, one of the founders of Industrial Works of Bay City.

The Dill Steam Shovel, as reported in the April 29th, 1881, edition of the Railroad Gazette, was claimed to be the first steam shovel to operate on standard-gauge railway track. It was a railroad-type shovel mounted on a six-wheel carriage, with a vertical boiler at the rear and a boom at the front capable of swinging about 90 degrees, left or right.

The Dill or Clement shovel seems to have been manufactured for a relatively short time. The crowd and swing designs probably contributed to its downfall, as very long steam cylinders were deployed to apply their motions. The crowd cylinder, boasting a 10½in bore and an eight-foot stroke, was directly connected to and moved with the dipper handle, thereby subjecting it to a multitude of stresses and strains.

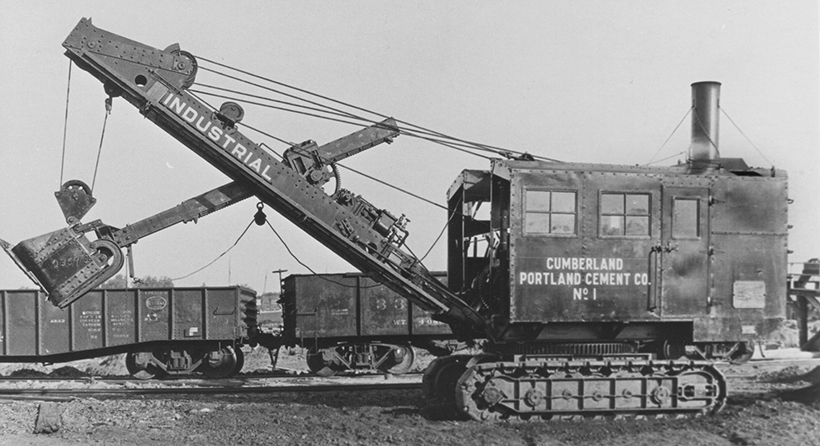

The Industrial Works Type DC steam convertible 7/8-yard excavator shovel, introduced in the early 1920s.

For the next two decades, Industrial Works withdrew its interest in excavators, to focus on designing and building many types of steam-driven cranes and lifting devices. It developed a line of well-respected and reliable breakdown cranes and pile drivers, which became its main products. By 1920, the factory employed 1,800 people and covered 29 acres, with buildings connected by a five-mile railway network. By 1923, the company reported that a total of 3,776 cranes of all types had been sold.

In the early 1920s, along with the emergence of several other American companies, Industrial Works re-entered the excavator field. It introduced the model DC, a fully-revolving, crawler-mounted excavator with a 7/8 cu. yard dipper, convertible to a dragline or 12½ -ton crane.

This Industrial Type DC doesn’t look like a steam shovel at first glance. I found it in a scrap yard in southern Alberta.

Although most of its competitors at that time were introducing excavators powered by internal combustion engines, Industrial Works chose to use steam for its new excavator, probably because, for decades, most of its other products had been steam-driven.

Except for its vertical boiler at the rear, the external appearance of the DC resembled a diesel-powered machine of its time. Clutches and brakes were operated by a bank of levers and foot pedals at the front of the machine, and the crawler drive sprockets were driven by a series of shafts and bevel gears. In 1926, Engineering New Record reported that the DC excavator had received several improvements, including a positive steering arrangement featuring friction clutches. It was also offered with petrol, diesel or electric power options.

In 1927, Industrial Works merged with the Brown Hoisting Machinery Company of Cleveland, Ohio; a company with a similar background, to establish the new company, Industrial Brownhoist Corporation. Brown Hoisting Machinery, founded by Alexander E Brown in 1880, designed and built a variety of material-handling machinery, including railway wagon dumpers, special cranes for shipyards and docks, and locomotive cranes. In 1921, the company fitted crawler tracks to one of its standard, petrol-driven, fully-revolving No.2 locomotive cranes, and modified it to operate as a dragline or grab.

Industrial Works stated it had built 3,776 steam cranes by 1923. Here’s one example of the many types.

Soon after Industrial Brownhoist was established in 1927, the company consolidated the excavator designs of both companies, and announced a range of models in five sizes, from ½ to 1¼-cubic yard capacity. No steam machines were listed after 1930 and, although the company advertised excavators with several improvements over the years, excavators appeared to have been just a sideline, playing a relatively minor role in the company. Industrial Works excavators were never built in significant numbers, which explains why so very few are seen now, and none are known to be preserved. I’ve only encountered one in all my travels; a model DC in a scrap yard in southern Alberta.

On the other hand, Industrial Brownhoist was a major player in other fields of special lifting equipment, dockside material-handling equipment, locomotive cranes and pile drivers. By 1950, the company boasted it had built ‘more than 20,000 cranes of all types’.

From 1953, Industrial Brownhoist passed through several different ownerships until 1960, when American Hoist & Derrick Company (AH&D) of St. Paul, Minnesota, purchased the company. It continued to operate at Bay City, Michigan, as the Industrial Brownhoist Division until 1983, when the factory closed. With a move to Wilmington, North Carolina, in 1985, and a change of ownership to American Crane Corporation in 1987, AH&D finally became part of Terex Corporation, in 1998.

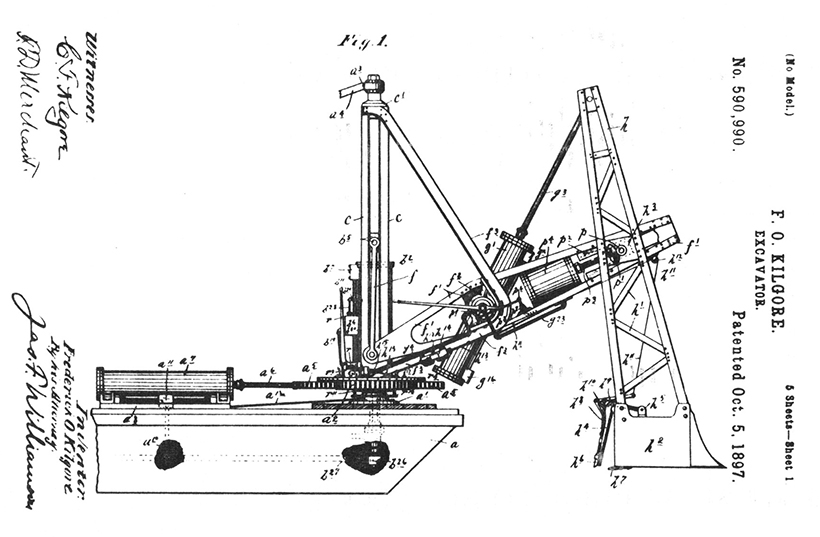

KILGORE

This rare shovel of a very unusual design was patented in 1897 by Frederick O Kilgore, and manufactured by the Kilgore Machine Company of Minneapolis, Minnesota. All its digging motions were achieved with long, steam cylinders, thus dispensing with the usual hoisting engines, drums, chains, clutches and pulleys. However, the machine was propelled by use of gearing and chains from a separate steam engine.

A drawing from Kilgore’s original patent documents, dated 1897. Digging motions were achieved by the use of large, steam cylinders, instead of chains or ropes.

The best description of the Kilgore steam cylinder arrangement can be found as quoted from Engineering News (Volume L, No. 25, dated 1903). ‘The action features four, direct-acting steam cylinders used in digging and swinging, and one small, direct-acting cylinder for tripping the dipper. Within the mast is a vertical cylinder, from the crosshead of which are suspended cast steel links or connecting rods whose lower ends are attached to the heel of the boom. This cylinder raises and lowers the boom, and raises the dipper when making a cut (see sketch).

‘Pivoted to the main fulcrum of the boom is an oscillating cylinder, having its piston rod attached to the heel of the dipper arm or handle; this is used to swing the arm. The third cylinder lies within the boom, and its piston rod is attached to another, cast-steel crosshead to which the dipper arm is pivoted. This cylinder is used to give a direct thrust to the dipper. The fourth cylinder is placed horizontally at one side of the deck or floor, and has attached to its piston rod a heavy, steel rack which engages with a steel spur gear on the foot of the mast. This serves to swing the mast and boom.’

Since no good Kilgore photographs could be found, this engineering drawing will have to do. It’s the 65-ton shovel with horizontal boiler; the larger of the two sizes offered.

Two sizes of Kilgore railroad shovels were offered; a wheel-mounted 30-ton model with 1¼-yard capacity, and a rail-mounted, 65-ton model with 2½-yard capacity.

In the aforementioned publication of 1903, it was stated that only ‘two or three’ Kilgore shovels had been put into service. One worked at the Chicago Sand & Gravel Company, but wasn’t a success according to an operator who, in 1904, was hired to operate it. He stated: “The machine was stripping about six feet of sand from the gravel, but seemed to be getting nowhere with it. I didn’t feel that the shovel was a success, so I refused to operate it, and the gravel company never accepted the shovel. Power was spent quickly with no results, as this machine would not dig the six foot of sand without stalling in the bank.”

In 1904, it was reported that only a total of five Kilgore shovels had been built. The following year, the Kilgore Machine Co. merged with Petler Car Works of Minneapolis, and became the Kilgore-Petler Company, with the intention of building Kilgore shovels, but it’s understood that no more were built.

THEW

Early in the 1890s, Captain Richard P Thew carried iron ore by ship on Lake Superior from ports in Minnesota, Wisconsin and Michigan, to steel mills near Cleveland, on the southern shore of Lake Erie. The limited-slew, rail-mounted equipment used for handling the stockpiled ore was slow and inflexible, often causing delays of several days before the ship could unload. Captain Thew became frustrated and, in 1895, designed a ‘portable shovel’ with a telescopic crowd motion and mounted on broad, road wheels. Built by the Variety Iron Works, of Cleveland, Ohio, it was claimed to be the first, fully-revolving shovel manufactured in the United States.

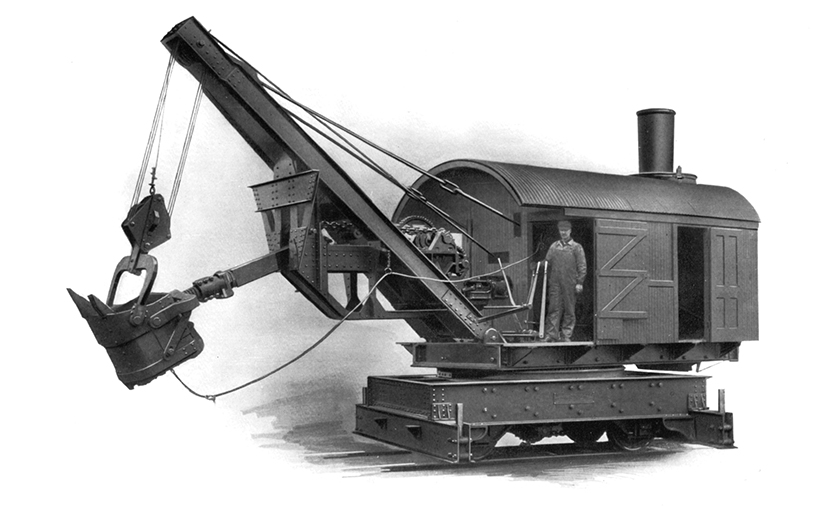

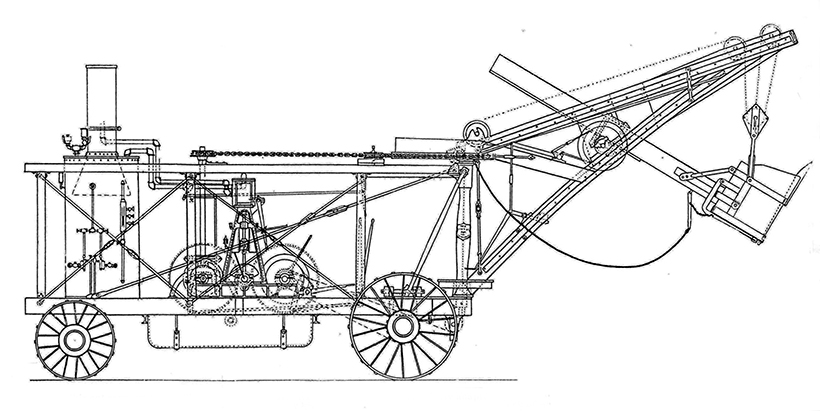

A drawing of the original Thew shovel from 1895, featuring a horizontal crowd arrangement.

Following its success, Thew decided to build his own machines, and established the Thew Automatic Shovel Company at Lorain, Ohio, in 1899. Demand was high so, by 1911, the company was promoting six sizes of steam shovel, mounted on rails or steel wheels in sizes from 5/8 to 1¾ cubic yards capacity. In addition, the company offered two sizes of gasoline shovels, and seven types of electric shovels, including some for underground operation.

Thew Type No.4 was the largest of the Thew steam shovels, with a 1¾ cubic yards capacity.

By this time, all models were still offered with Thew’s telescopic crowd, but a conventional rack-and-pinion crowd boom was also available. A 1925 brochure made no mention of the telescopic crowd, indicating that this had been discontinued in favour of the conventional, rack-and-pinion crowd. The popular Type O, ¾-yard capacity shovel stayed in production until 1929.

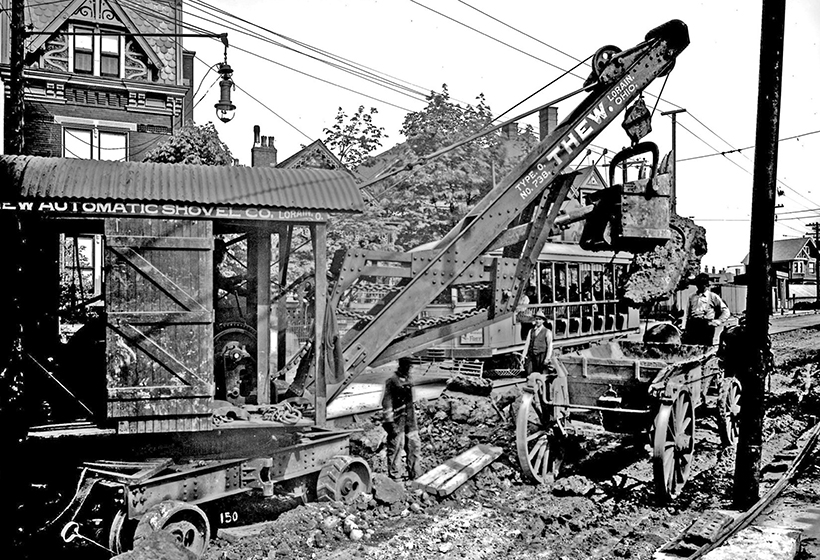

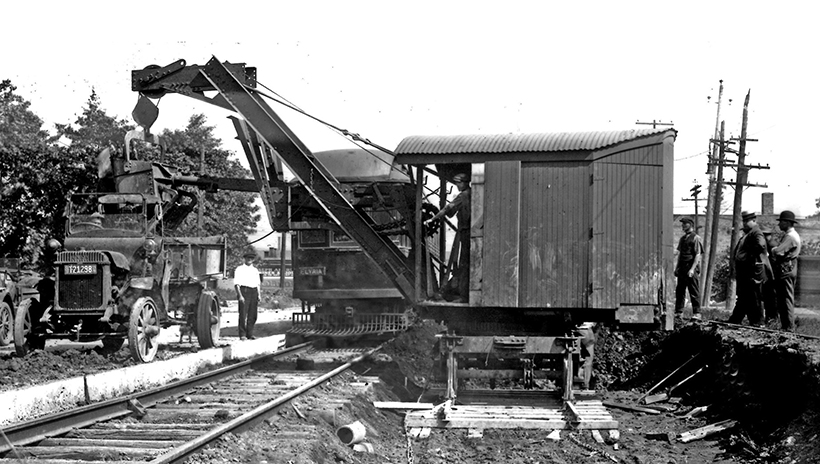

One of the popular ¾-yard Thew Type O shovels, busy on street work.

In 1920, Captain Thew retired and sold his interests in the company, which was then renamed the Thew Shovel Company. Demand for shovels in the ‘roaring twenties’ sky-rocketed, and Thew became one of the leading shovel companies in America in terms of number of units sold. The last Thew steam shovel was built some time in the 1920s and, at that time, the brand name ‘Lorain’ was adopted for Thew excavators, after the city where the machines were manufactured.

The horizontal crowd system can clearly be seen in this action photograph of a Thew Type O. By 1925, the horizontal crowd motion had been replaced on all Thew models by a conventional, crowd type with shipper shaft.

Lorain-branded excavators and mobile cranes became well-known the world over, with thousands sold to the armed forces during World War II. In 1964, the Koehring Company of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, took over the Thew Shovel Company, which then became the Thew-Lorain Division of Koehring.

Another Thew Type O on railway work. Here it’s seen loading a truck built by Union Motor Truck Company of Bay City, Michigan.

VICTOR

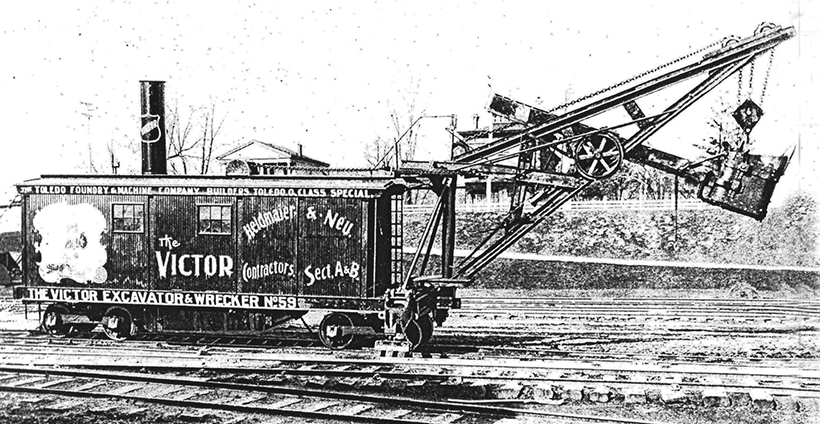

Victor was the trade name bestowed on steam shovels built by the Toledo Foundry & Machine Company of Toledo, Ohio. This company was incorporated in 1880, and was a successor to a business established some 15 years earlier. Its main products were dredges, pile-drivers and steam engines. In the early 1880s, it began building steam shovels to the design of HT Stock, who’d previously enjoyed a long involvement with steam shovels, including operating the first Otis shovel.

Mr Stock was an inventor, contractor and manufacturer. He held a patent dated March 1883 for a ‘Railroad Ditching and Excavating Machine’ (steam shovel). He didn’t actually build the machines himself, but had them built on a royalty basis by the Vulcan Iron Works at Toledo and, from about 1886, by the Toledo Foundry & Machine Company.

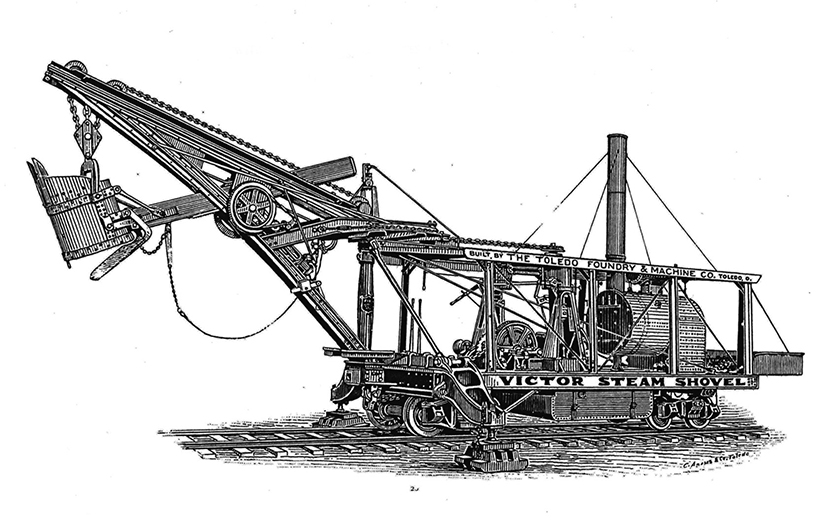

A drawing of the Class 4 ‘Baby Victor’ steam shovel. This ¾-yard-capacity shovel on wheels was designed for city work.

Stock’s first shovel was called the ‘Jumbo’ and boasted an all-steel undercarriage mounted on standard-gauge rails. The swing engine was mounted on the roof, a pair of rotary valve engines powered the hoist, and twin crowd engines were mounted on the boom. Bucket capacity was two cubic yards. When Toledo Foundry began manufacturing the machines, they were named ‘Victor’, and Mr Stock became a vice-president of that company.

During the 1890s, Victor shovels were greatly improved. An 1899 catalogue claimed ‘Victor shovels are built on scientific principles. The car bed, floor, house frame and all other structural portions are of the best quality of beams, channels, plates and angles, shapes expressly made for the purpose, and so distributed and proportioned that when in the process of excavating the stiffest clay or hard pan, no part of the shovel is subjected to strains exceeding 50% of the elastic limit of the material of which it is composed.’

A Victor steam shovel from the 1880s, designed by HT Stock.

The 1899 Victor catalog describes a range of six different shovels ranging from ¾ to 2½ cubic yards capacity. The largest was named the Victor Special. It weighed 60 tons in operation, and came equipped with double, 10½x12in twin hoisting engines, and double 7x7in crowd engines on the boom. Other Victor shovel models were known by Class numbers; A-1, 1, 2, 3, and 4, with operating weights from 16 to 48 tons.

The Victor ‘Special’ Class 60-ton railroad shovel with 2½-yards capacity, built by the Toledo Foundry & Machine Company.

The Toledo Foundry & Machine Company continued in business into the 20th century, and advertised as manufacturers of Victor shovels, dredges, pile-drivers, milling machinery and marine and stationary engines up to the mid-1920s. The shovels appeared to receive little in the way of updates or improvements, and the actual date of the last machine remains unknown.

For a money-saving subscription to Old Glory magazine, simply click here