Clay from the Cornish ports

Posted by Chris Graham on 21st June 2020

David Vaughan takes a nostalgic look at the industrial infrastructure that made the export of clay from the Cornish ports a viable proposition.

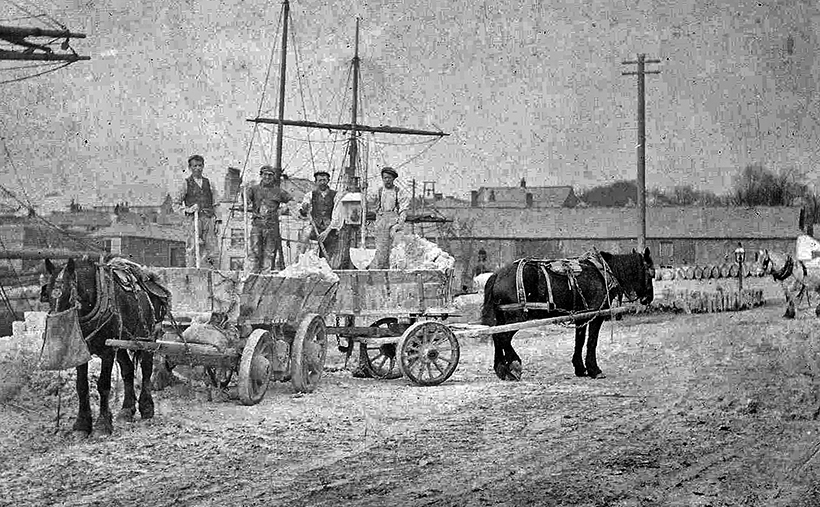

The export of clay from the Cornish ports: Early days at Charlestown, with clay being unloaded form horses and carts. There was a steep hill into the little port, and the wagon wheels had to be scotched on the descent.

In the early 1960s, just before I started to go out to work in the real world, my parents and I had a caravan holiday somewhere between St Austell and the port of Par, on the Cornish channel coast. It was that holiday that gave me my introduction to the fascinating and influential industry that grew out of exporting clay from the Cornish ports.

I remember seeing, for the first time, the so-called Cornish pyramids; mountains of waste sand and mica from the china clay mining industry. I also recall the branch lines that served the clay dries, and was fascinated by all this because there was no mining or, indeed, any other heavy industry of the type, in my home county of Sussex.

Memorable first sight

I remember taking a walk along a ridge to see some dump trucks, both Euclids, that were parked together with a Caterpillar bulldozer. Then, looking over the edge of the hill, I saw the port of Par laid out below for the first time, with lots of ships, lorries, cranes and internal railway lines. It seemed like heaven to me and, as soon as I could, I found a way down to the port. The first thing I saw was a man coming out from under a very low railway bridge, over which ran the main ex GWR main line to Penzance.

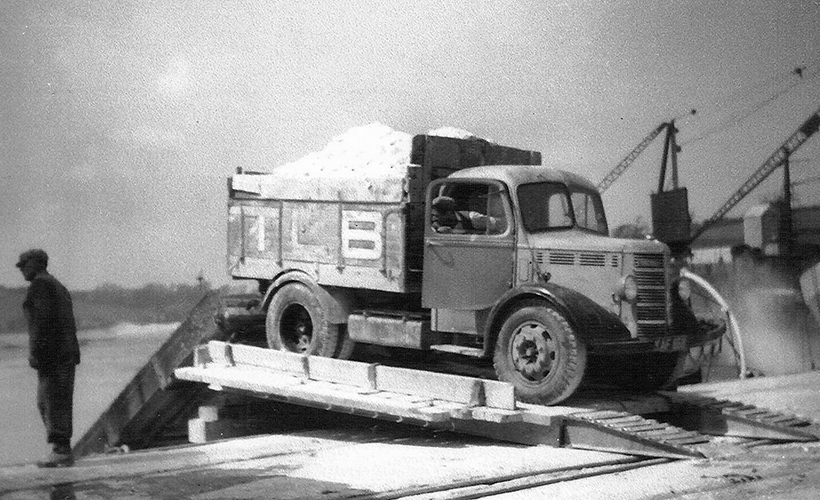

On the opposite side of the port from the china clay loading chutes, coal is seen being discharged from a coaster into a Thames Trader tipper with extended sides, 810 JRL (Cornwall, 1960) some time in 1962. The 22RB crane was owned by The Charlestown Estate, which is the port authority.

He put a barrier across what was then a main coast road, then poked a long pole with a red flag on the end under the bridge; an action that immediately aroused my curiosity. Then, to my delight, a little saddle tank engine with a very low cab came out from under the bridge and crossed the road, pulling a train of wooden wagons, covered in a white, dusty substance.

They were, I subsequently learned, ‘empties’ on their way to Par Moor clay dries. I crossed the road and gingerly looked under the bridge. Being a bit wary having been chucked off such sites in the past, I sidled along the dock road, and came to a little engine shed, outside which another saddle tank was being made ready for service. I asked if it was all right to take a picture or two, and got out my trusty Ensign box camera. I was well and truly hooked with the whole scene, and so began an interest in the China Clay industry that’s remained until recent years.

This view of Par harbour was taken in August 1963, around the time of my first visit to the port, showing coastal shipping being loaded from the quayside railway lines, with one of the little Bagnall saddle tanks on a train of clay wagons. On the West Arm of the port, road traffic – including an early ERF – was being unloaded using grab cranes and conveyors.

In this article, I intend to give a brief outline of the various ports which were associated with the shipment of China clay, to elsewhere in Great Britain, and countries all over the world. With the help of the China clay History Society, I’ve amassed some archive photographs, mainly of activity at Par, but also including Charlestown and Fowey, some of which I’m pleased to be able to share with you here.

Creating a port

Charlestown was originally a small fishing village called West Polmear but, with the mines and clay pits around St Austell flourishing in the later part of the 18th century, the need for a port became obvious to a local businessman by the name of Charles Rashleigh. With help of the famous lighthouse designer, John Smeaton, he began the mammoth task of creating a port from scratch.

This involved blasting rocks, building a harbour arm and lock gates plus a ‘leat’ – or watercourse, – to bring water from the Luxulyan valley, which was stored in reservoirs to keep the level of the dock up at low tide. The port soon flourished and the village became a small town, which was named Charlestown, in Charles Rashleigh’s honour.

In May 1955, we see a Bedford O Series belonging to Taylor Lowe Brothers, delivering clay directly into the hold of a ship from a portable ramp and chute at low tide. The coaster was obviously ‘taking the bottom’; the term used for a vessel sitting on the mud at low tide!

It was, by reason of the layout of the land, always a small port, with little scope for further development. But the nearby clay pit at Carlease provided much business, with the processed clay being pushed in small wagons, via a tramway in a tunnel, to the port where it was loaded on to ships using chutes along the harbour wall.

The local roads were steep and poorly-surfaced, so it wasn’t until much later that lorries started to use the port. Those that did were mainly owned by the smaller, clay producers. The town was, however, the first base for the firm known as the Heavy Haulage Company Limited, founded in 1919 to haul clay, coal and cement. This was the main provider of lorries for the clay industry, and was taken over by ECC in 1948, along with other local transport companies.

Charlestown remained a working port until quite recently, but the narrow harbour entrance prevented the use of larger vessels, so most clay traffic was shipped out from Par and, later, Fowey, as we shall see. Today, Charlestown is still a picturesque little port with a very interesting museum detailing, among other things, the area’s involvement with local smugglers. The remains of the clay tunnels and chutes are still there, however.

The Kathleen May was the last sailing ship to visit Par as late as 1955. A Bedford tipper was unloading clay on the quayside.

Par harbour was built in 1829 by a local entrepreneur, Joseph Thomas Treffry, who was known as ‘The King of Mid-Cornwall’. With the coming of heavy industry during the Industrial revolution, there was an ever-growing need for better and safer harbours. Treffrey had an urgent need for a harbour to serve his mines and quarries. He built an aqueduct to bring ore from the Luxulyan valley, a canal linking Par with Ponts mill and, later, a standard-gauge railway to Bugle, worked by horses and a rope-worked incline.

A major success

At that time, Fowey didn’t have a rail link, and its narrow streets to the harbour hampered the progress of horses and pack mules. Par provided safe haven for up to 50 small, sailing vessels, and larger ships that took on cargoes from barges, lay at anchor in the bay. The disadvantage of this harbour was the fact that, at low tide, ships ‘took the bottom’ (ie sat on the mud!). Nevertheless, the port became the major place for clay exports via coastal shipping and, by 1956, the harbour was dealing with 800 ships a year.

The port became wholly owned by English Clays Lovering Pochin and Co in 1946 and, in 1961, major alterations were carried out to increase loading capacity and to accommodate the growth of road transport, as the original port depended on being served by rail. At its height, Lloyd’s list described Par as ‘The busiest small port in the country,’ and up to 30,000 tons of clay passed through it in one week alone.

On the West Arm in 1963, a Leyland Comet Scammell coupling artic, 876 DAF (Cornwall, 1958), of ECC’s ‘Heavy Transport’ fleet, is seen unloading bagged clay via one of the port’s own 22RB cranes.

When I first visited Par, it was a hectic and heady mix of lorries and railway wagons, but my limited stock of film – and restricted public access – meant that I regrettably took very few photographs. In 1968, the railway link through Pinnock tunnel to Fowey was replaced by a single-track road for lorries. The port facilities were given over to bulk, which reduced the loading time for ships and, following a major rationalisation of the industry by the new owner, Imerys Minerals, in 2008, Par harbour was closed and all shipping was transferred to Fowey. Today, the site is still served by rail and road, but has extensive bulk clay storage and some large rotary clay driers.

Fowey wharves, as distinct from the ancient port of Fowey, were owned and operated by the Great Western Railway, then by British Railways. There’s a deep water, sheltered port in the heavily-wooded valley that runs from Lostwithiel to the sea. The first rail-served jetties were built for the iron ore trade in 1874. In the early 1920s, the GWR increased the capacity of the port, and modernised the jetties, providing conveyor loading systems and electric windlasses for moving wagons of china clay.

In 1968, English China Clays leased the clay jetties from British Rail and, as already mentioned, the rail link from Par was lifted and replaced with a lorry road, leaving the main railway link via Lostwithiel and St Blazey. Road traffic from Par, through the ¾-mile-long, single-line railway tunnel, was controlled by traffic lights.

In 1963, a Foden S20 eight-wheeled tipper, 12 BRL (Cornwall. 1958) of The Heavy Transport company, is seen discharging on to a conveyor at Par.

Today, Fowey remains the biggest port for the export of clay products and, indeed, rather like sending coals to Newcastle, it also handles imports of clay from countries such as Brazil, which is then blended with Cornish clays to go into the many diverse uses of clay ranging from pharmaceuticals and plastics to paint and beauty products.

Finally, I must offer my sincere thanks to Ivor Bowditch, and to members of the Cornish Clay Historic Society, without whose help and archive pictures, this article wouldn’t have been possible.

A colour photo of a Leyland Comet Scammell coupling artic, 876 DAF (Cornwall, 1958), of ECC’s ‘Heavy Transport’ fleet, seen unloading bagged clay via a 22EB of Western Excavating, at Par in May 1965.

Moving on to July 1967, an Ergo-cabbed Leyland Octopus, JAF 119E (Cornwall, 1967), is seen discharging directly to a ship via a conveyor at Par, while a Foden S36 awaits its turn.

Although we can’t see much of the lorry being used here, this was an experiment in palletised ClayPac loads. The spectators seem to have included a number of ‘management types’!

Loading bagged clay on to a ship with a Coles mobile crane.

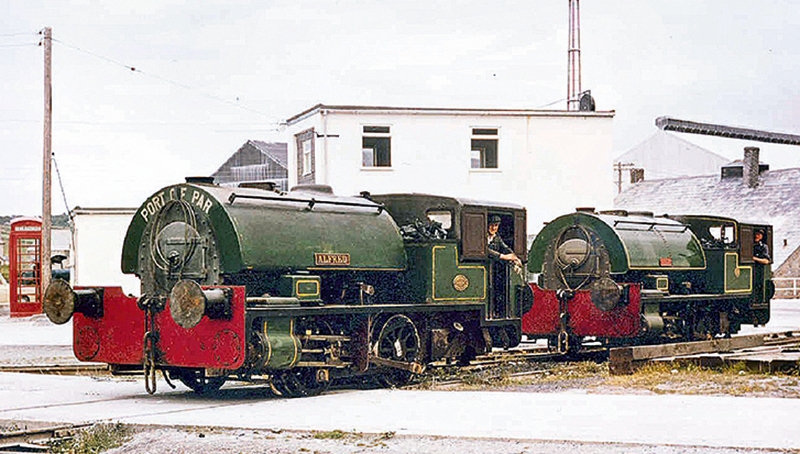

The two Bagnall saddle tanks, named Alfred and Judy (later made famous as Bill and Ben, in the Thomas the Tank Engine books and now preserved on the Bodmin and Wadebridge Railway), as I saw them in the early 1960s, still hard at work.

For a money-saving subscription top Vintage Roadscene magazine, simply click here