Exploring the polar regions

Posted by Chris Graham on 16th February 2020

Exploring the polar regions is incredibly tough and unforgiving on both man and machines, Ed Burrows recounts some of the earliest, mechanised expeditions

Until a magnificent failure got Antarctic ice on its face in 1940, exploring the polar regions regions was quite literally a dog’s life. The Inuit people of the northern extremities of North America, showed the way. The type of husky-drawn sled that served them from time immemorial, was borrowed by the 1911-1912 Antarctic expeditions that raced to be first to reach the South Pole. The Norwegians, led by Roald Amundsen, used dog sleds to claim its historic victory on December 14th, 1911.

The Brits, led by Scott – beaten into second place by 34 days – used a combination of dog teams, ponies and primitive (though, in their way, pioneering) motorised tracked contraptions. The ponies were eventually killed and provided food for dogs. While Amundsen travelled light and kept it simple, the Brits were overloaded and, evidently, not as good at working with dogs.

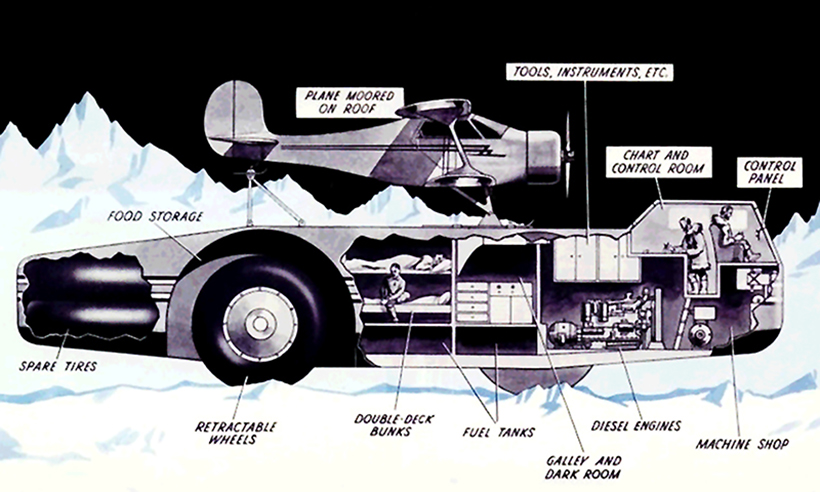

Built in 1939, the US South Pole expedition’s Snow Cruiser was probably the world’s largest, pneumatic-tyred vehicle built up to that time.

Antarctic Snow Cruiser

With your snow shoes on, best foot forward to 1939. Starship of the US expedition, led by Admiral Byrd to the planet’s nether regions, was the Antarctic Snow Cruiser. Utterly without precedent in every respect, like something from the realms of sci-fi fantasy, it even carried – piggyback style – a ski-plane on the roof structure above the crew’s living quarters.

Conceived in an age when polar exploration excited the world’s newspaper headlines – just as the first ventures into space did two decades later – the Snow Cruiser fell a crevasse short of doing what it said on the box. But you’d be forced to concede in no other sense was it a failure. That it was constructed at all – and in an astonishingly brief eleven-week race against the clock – was a spectacular triumph of American can-do spirit and engineering ingenuity.

Admiral Byrd’s Antarctic behemoth can be viewed as a precursor of the Space Shuttle – or a Winnebago running on 10ft diameter tyres. The driving force behind it was an earlier 1933-1935 expedition’s second-in-command, Dr Thomas Poulter. After returning to America, he took up the position of scientific director of what was then the newly-established Research Foundation of the Armour Institute of Technology, in Chicago.

The Armour Institute Research Foundation was the ideal home for his innovative thinking. Its raison d’être was to ‘render a research and experimental engineering service to industry; to conduct fundamental research for the purpose of improving our comforts of life and knowledge of science’. Snow Cruiser design work, commenced in a part-time basis stated in 1937. Over the next two years, the project advanced from ‘blue sky’ thinking to finalised engineering drawings. Right down to electric wheel drive with traction motor hubs, the innovation was such that the brief might well have been ‘do not, under any circumstances, do what anyone else had done before’.

New mission set

In spring 1939, the US Government announced the decision for an Antarctic expedition to catch the next Polar summer. This necessitated departure in November of 1939. The Armour Institute Research Foundation presented the completed plans for the Snow Cruiser and the Government said yes – oblivious to the fact that a vehicle that was tantamount to the re-invention of the wheel, would have to be built in only three months. The timeframe would be unimaginable today – computers certainly seem to slow things down!

Literally a traveling scientific laboratory and mobile exploration base, the Snow Cruiser had an on-board machine shop, storage space for months of provisions and heated, insulated living facilities to sustain a crew of five men (and a dog).

Actual construction was undertaken by the Pullman organisation in Chicago, famous for building and operating luxury railway sleeping and dining carriages. The scale of the construction task is only hinted at by the Snow Cruiser’s whale-like weight, dimensions and capacities. Designed for operating at a gross of 37.5 tons, its overall length was 55.7ft, height was 16ft and width was an inch and a half short of 20ft. The wheelbase was 20ft; front and rear overhangs were each 17ft 10in.

It had tankage for 9,464 litres of diesel – sufficient for an estimated cruising range of 5,000 miles – together with special engine and drivetrain bearing lubricants formulated to keep things moving at -50°C. Befitting its role as aircraft carrier for the expedition’s Beechcraft Model 17 Staggerwing five-seat bi-plane, the Snow Cruiser also carried 3,786 litres of aviation fuel.

All-in-one mobile exploration base, scientific laboratory, workshop and aircraft carrier. An on-board crane lifted the Staggerwing biplane on an off.

The electric-welded, all-steel structure comprised I-beam chassis members carrying a spaceframe that was sheathed in varying gauges of steel sheet. The I-beams slightly protruded from the underside, to act as skids if the vehicle bottomed.

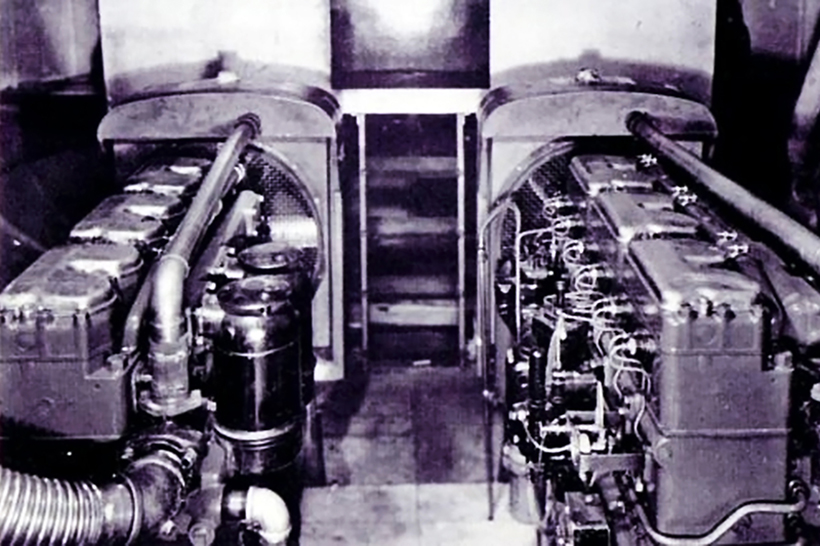

General Electric and Cummins were responsible for the diesel-electric drive system. Eliminating the space that would otherwise have been taken by a gearbox, propshafts and axles, drive was taken to the wheel-hub traction motors by electric cable. Installed in an engine compartment below the ship-style chart room, a pair of naturally-aspirated 112kW/150hp, six-cylinder Cummins diesels drove a GE generator. The four hub motors were each rated at 56kW/75hp.

The engine bay’s twin Cummins diesels – combined 300hp output – drove a General Electric generator set from which power was fed to the electric hub motors.

Tyre problems

The 12-ply, 10ft diameter, low-pressure Goodyear tyres were of a type previously produced for swamp buggies of the sort used for prospecting in the Louisiana swamplands. Each tyre had a two-square-foot contact patch, and could run at between 2.5 and 15psi inflation pressure. Though expedient given the novelty and timeframe, the decision to use tread-less rubber was to prove a serious error of judgement; the conditions encountered in Antarctica required grip the tyres simply didn’t possess.

All four wheels steered – with the same turn angle, or crabwise at opposite angles front and rear. To allow for tobogganing across crevasses with a flat underbelly, the wheels were retractable. The front wheels retracted until the front of the underbody was at the other side of the gap, at which point the rears were retracted and the front wheels were lowered and powered the vehicle out. That was the theory, anyway.

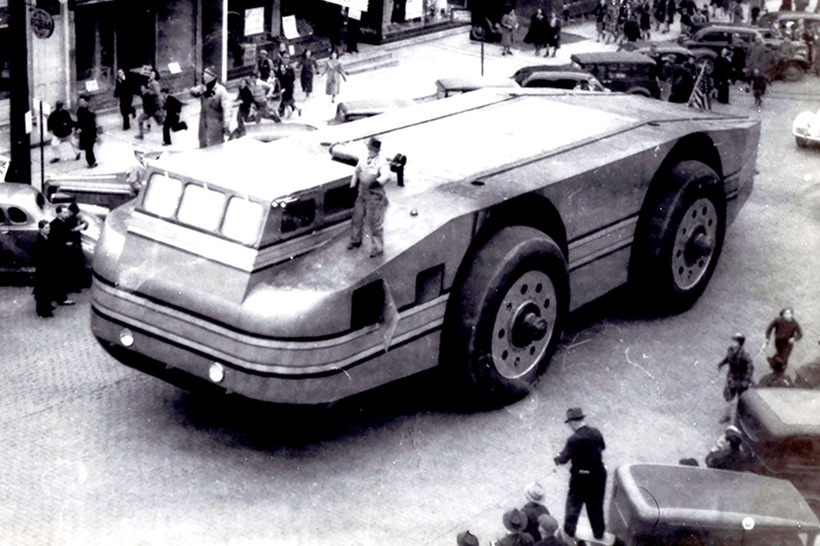

Leaving Chicago on October 24th, instead of the envisaged eight days, the 1,021-mile journey to Boston took nearly three weeks. Often, the road was barely wider than the Snow Cruiser. Generating massive excitement all the way, it crossed bridges with fractions to spare and, at one stage, caused a 72,000-vehicle tailback. The Snow Cruiser’s somewhat clumsy progress was watched by an estimated 2.5 million people. Incidents en route included a collision with a truck, hitting the corner of a bridge and careening downhill and coming to rest in the middle of a cow pasture, nose buried in a mud bank!

The 1,021-mile journey from Chicago to Boston, for shipment to Antarctica, caused traffic hold-ups for much of the way.

The Army Wharf, Boston, was finally reached on November 12th. Ooops! The Snow Cruiser was wider than the beam measurement of the expedition’s ship, necessitating the removal of nine feet from the tail section that housed the two spare tyres.

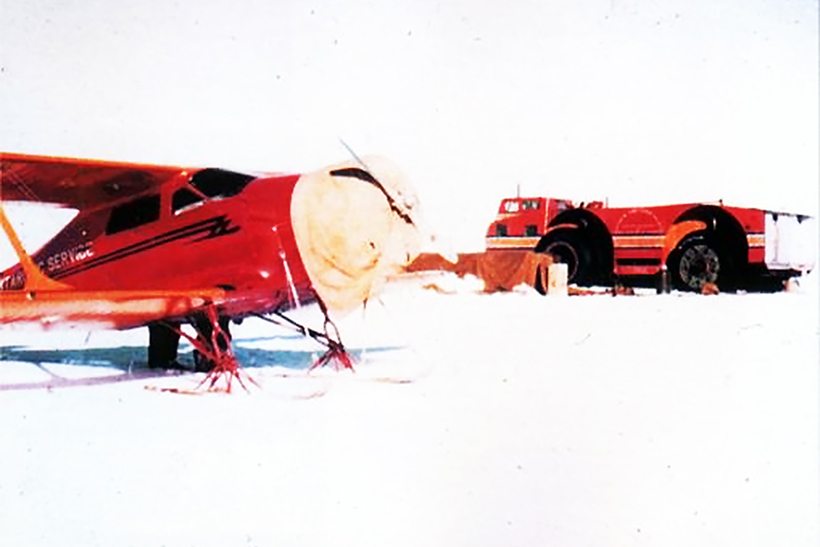

Colour photography was in its infancy in 1939 and this print may have been processed in the kitchen-cum-darkroom. The Snow Cruiser was wider than the ship’s beam. Once on board, the tail section had to be cut off.

Rather than in cabins on the ship, expedition members slept aboard the Snow Cruiser and, during the two-month voyage, were kept busy installing equipment there had been no time to fit before departure.

Although the distance from the ledge of sea ice where the Snow Cruiser disembarked wasn’t great, its deficient mobility was soon found out. To improve traction, the spare tyres were fitted to the front wheels and chains to the rears. Never performing as hoped, the Snow Cruiser was finally parked near one of the base camps and used as living quarters, never to move again. In late 1940, the expedition itself was abandoned, a year before America entered the Second World War.

Mechanical options

For operation in the polar regions, which is best, wheels or tracks? And big wheels with electric drive – or more conventional transmissions? History records 1955 as the year each of these was put to the test.

In the Antarctic, exploration got going again, with a highly successful expedition jointly mounted by the UK, the US, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa. Four-track Sno-Cats were the primary mode of transport. Built by the US Tucker Sno-Cat Corp of Oregon, power was provided by a 180hp, 5.4-litre, twin-carburettor Chrysler Hemi V8. Today, Tucker continues to build bonneted and cab-forward evolutions of its original four-track design.

In 1956, a pioneering convoy of 164-tonne gross Mack LRVSW tractor/65-ft trailer rigs trekked 1,500 miles over virgin territory, to the fringes of the Arctic Ocean.

In the 1950s, Antarctic exploration resumed using a fleet of highly successful, four-track Tucker Sno-Cats.

Again in 1955, following earlier tests with proof-of-concept vehicles, a new-generation, diesel-electric leviathan with hub-motor drive – the LeTourneau V-22 Sno-Freighter – set forth, this time northbound towards the fringes of the Arctic Ocean. Operated by Alaska Freight Lines under contact to the US military, its mission was delivering material to Distant Early Warning radar chain construction sites. The DEW Line, one of the Cold War’s biggest single defence projects, employed an estimated 25,000 people working in the electronics, civil engineering, construction and transportation sectors. The chain comprised some 60 radar units stretching 3,000 miles across Alaska and Northern Canada – and extending to Greenland, the Faeroes and Iceland. It roughly followed the 69th parallel, nearly 200 miles inside the Arctic Circle.

With electric hub traction motor drive, the LeTourneau V-22 Sno-Freighter power car/five-trailer outfit was designed, built and tested in only six weeks.

Thanks to Texan earthmoving plant innovator RG LeTourneau’s modular custom-build engineering techniques and flexible manufacturing system, the VC-22 was designed, fabricated and tested in just six weeks. The structure was all-welded, steel and, to save weight wherever possible, aluminium. Comprising a four-wheel power car and five 25-ton payload, 40ft long, four-wheeled trailers, it ran on 88in diameter/38in tread width tyres. Overall train length was 274ft.

Power car spec

The power car’s twin 400hp Cummins units powered an LeT combined AC/DC genset, from which power was taken to the VC-22’s 24 wheel-hub traction motors. The power car’s living and sleeping accommodation provided for a crew of four. The coupling system was designed so that, despite five trailers, the rig left only one set of wheel tracks.

The Sno-Freighter ran on a 400-mile trail, pre-prepared by a team of Caterpillar D8 bulldozers. The trail was subsequently widened, and easy going enough for a convoy of 32 Kenworth linehaul outfits to make the trip. A construction schedule requiring the DEW Line to go live only three-and-a-half years after it was conceived, also demanded other transportation resources. Most impressive was a fleet of 11, specially-built Mack LRVSW tractors hauling 65ft long semi-trailers. In this instance, the convoy’s 1,500-mile trail – largely through virgin landscapes – was blazed by its own bulldozers travelling immediately ahead.

Alaska Freight Lines was again the contractor. The overarching consideration was beating the 1956 spring thaw. Surface conditions dictated the haul was only feasible in winter because, during the spring thaw, the tundra – the area roughly between the tree line and the 75th parallel – becomes an impassable bog of grasses, sedges, lichens, and willow shrubs.

The LRSVW 6x4s were moved 2,500 miles by rail, from Mack’s Allentown factory to Alaska Freight Lines base in Seattle.

The LRVSWs were ordered in November 1955, and Mack’s engineers pulled out all the stops. Nine weeks after the order was placed, the trucks were moved by rail and reached Alaska Freight Lines’ Seattle base, 2,500 miles from the Bulldog’s manufacturing plant in Allentown, Pennsylvania.

The tractors were the prime mover derivative of Mack’s 34-ton payload LRVSW 6×4 off-highway dump truck. Between 1954 and 1961, Mack built a total of 209 LRVSWs – so, rare beasts, though few other trucks boasted 600hp at the time.

The LRVSW tractor unit weighed in at 22 tons. Its main dimensions were: length 27.5ft; wheelbase 16.8ft; front track 8.3ft. Overall width across the extremities of the rear tyres, 11.5ft. Height to the top of the cab was 10.8ft. The chassis was an all-welded, tapered-frame structure utilising wide-flange, 14.25in deep I-beam main members, for maximum torsional rigidity.

The 600hp of the LRVSW was almost unprecedented for a truck 65 years ago – it’s still pretty awesome today!

Massive power output

Power was provided by a 28-litre Cummins VTA28 turbocharged V12 diesel, a 40° V-design developing maximum outputs of 600hp and 1,600lb/ft of torque. Transmission was through a Mack two-lever manual shift Duplex gearbox, with eight forward speeds and two reverse. Drive was taken to a Mack Planidrive dual reduction axle bogie, with inter-axle and differential power dividers. The rear suspension system incorporated upper and lower semi-elliptic spring packs, and allowed both axles a maximum upwards travel of 9in. Suspension of the undriven front axle was by semi-elliptics, assisted by shock absorbers. Tyres were 16.00x25s all-round, with chevron-treads and an outside diameter of 5ft. Wheels were suitably sized versions of Mack’s trademark, eight-spoke, rim-bolted arrangement.

In conditions that guaranteed progress for the most part would be at crawling pace at best, a prime mover/semi-trailer combination with a specified maximum grossing of 164 tonnes traversing 1,500 miles of nowhere, would inevitably require vast quantities of diesel oil. Notwithstanding a planned fuel stop 500 miles into the mission, the impossibility of refuelling at the final destination meant having to carry enough diesel for a round trip of 2,000 miles of tough going, plus adequate reserves. Ingeniously, fuel was carried in belly tanks under each trailer’s load platform.

Get out of that! It did – but everything had to be unloaded from the trailer when a rig got stuck.

In the 1950s, the regular mode of surface transport in the Artic region was a dog team and sled, reckoned to be capable of hauling a load of up to 200lb. Far into its 1,500-mile, off-highway trek across deep frozen hell, the convoy chanced upon a lone Inuit hunter with his dogs and kills-laden sled. From the vantage point of the front step grating of one of the tractors, he surveyed the convoy’s sheer scale and might. Touching the chromed Mack bulldog mascot crowning the radiator cap, he put what he was witnessing into Inuit perspective. “Many dogs,” he said, “Many dogs.”

Shown the Mack bulldog radiator mascot, the Inuit, who’d never seen a truck before, expressed the power and scale of the convoy as “Many dogs”.

Over and above the need for forging ahead day and night, temperatures far below freezing necessitated keeping the big Cummins running 24 hours a day. The only stops were for servicing, filling churns with ice or snow for fresh water and, weather permitting, mail and fresh vegetable deliveries by light aircraft. The downside to stopping meant the transmission cases had to be heated by blow torch so the gears could be shifted to get moving again.

Today, certainly for transporting medium and heavy equipment, the go-to manufacturer is Canada’s Foremost. Founded in the 1960s by Bruce Nodwell and his son Jack, the company’s pedigree derives from the Nodwell 110, introduced in 1957 and still in the Foremost line up alongside high flotation-tyred, frame-steer 4x4s, 6x6s and 8x8s, and 2- and 4-track transporters. Payload capacities range from 10 to 40 tonnes.

The Nodwell 110 began life as a five-tonner in 1957. Over six decades on, Foremost’s present evolution carries a 10-ton payload.

The original Nodwell 110 carried five tons. Its 32in wide flexible tracks – 40in wide on the 10-tonne payload current spec – ran on four pneumatic tyres on each side. Tracks running on wheels shod with pneumatic tyres remain the Foremost formula for ultimate, low ground pressure mobility over terrain you wouldn’t want to put your foot in. Between standing and walking, a man of average build exerts a ground pressure of between eight and 20 pounds per square inch. That compares with 4.3-psi at 6in penetration for Foremost’s Nodwell 110, at its maximum 25-tonnes GVW.

(Pics: Joel Dirnberger Archive, Foremost Industries, hankstruckpictures.com and Steven T Szalus, RG Letourneau University Museum, Mack Trucks Historical Museum, Tucker Sno-Cat Corp.)

To subscribe to Heritage Commercials, click here