The importance of ballast!

Posted by Chris Graham on 2nd September 2021

Bob Tuck takes a nostalgic look at the history and importance of ballast for heavy-haulage operators, and how its best contained.

The importance of ballast: Traditionally, the Showman’s world has long made use of ballasted tractor and trailer combinations. The law has allowed them to pull two or even three trailers, and enjoy a longer overall length limit than conventional artics or lorry and trailer combinations.

I can always remember the late Siddle C Cook talking about his frustration with carrying ballast. The conversation we had was probably about 40 years ago, but the point he made is still more than salient today: “What a waste of effort.” He did have a great idea to get around it which, as I’ll explain, was actually a development of what some box-tractor users already did, but – so far as I know – it’s never caught on. And yes, the industry has realised you just have to lump it – as you can’t get anywhere without it.

Seen on the A58 between Wetherby and Leeds, I’m sure this is the first ever photo that I took of a Scammell Junior Constructor. I’d been travelling with John Thompson and, after delivering a load of steel into the stockholder of Dunlop & Ranken, we were heading back for our home town of Consett. Seeing the Pickfords outfit coming towards us, John pulled onto the kerb with his Leyland Steer and I jumped out and ran across the road. John’s Leyland cab can be seen on the left of the picture. This shot is still a fantastic memory-maker for me.

Of course, the boffins will tell you that it’s simply the law of physics that hauling tractors which pull loads of weight do, in fact, need themselves to be weighed down with ballast so they can keep a firm grip of the roadway. It’s not rocket science, but what’s a pain is that the ballast carried by some heavy hauliers can mount up to 15, 20 or even 40 tons (or more) to ensure these vehicles can, in turn, haul two, three or even 400 tons of outfit.

The most stylish ballast box vehicle to be launched in 1945 must have been the purpose-built Scammell Showtrac. Bought new by Anderton & Rowland, ‘The Showman’ was the 17th – out of 18 – to be made specifically for the Showman’s world. Photographed by Peter Noble on The Stray at Harrogate in August 2016, it has been restored to pristine condition. (Pic: Peter Noble)

However – and this is the big one – it doesn’t mean that the way you carry this weight is something of an afterthought. Or, if you’re going to have a ballast box, let’s have a decent looking one at that. So, while you might not be surprised to hear how the following appreciation will end up with what I think is the finest ballast box combo’ of a motor you could ever want to find, I’m going to start with simply the most stylish period example of the genre. And I bet you never thought you’d read such words in Heritage Commercials. Yes, this is heavy stuff!

Built originally for wartime duties as a battle tank transporter, the Diamond T 980/981 subsequently proved a big favourite with many heavy-haulage concerns. We like how Pickfords modified its ballast box to make it more user-friendly. Because the T’s cab was so small, Pickfords also added a very small, tent-like compartment behind the cab, to provide space for the third man in its crew.

Made to measure

It was love at first sight. It must have been about 1958 when I first saw one of Pickfords’ Scammell Junior Constructors in the metal and, at that point, I was smitten as the streamlined, balanced look of this 6×4 ballast box tractor just took my breath away. True, I’ve since shifted those feelings to a huge variety of other creations but, of course, you never forget your first.

Not many vehicles were built specifically for civilian use during the Second World War, but Foden was to apparently build three specials capable of moving 100 tons. DDW 18 was to give Robert Wynn almost 20 years of solid service, as it was purpose-made to handle all manner of traffic.

In fairness, you could probably write this story on box tractors featuring Scammells alone, as that company built so many different types, but we promise a variety of appreciations to this versatile workhorse. However, there’s no time to dwell too long on the history of traction, with horses pulling a four-wheeled trailer but, of course, the historians among us will trawl up memories of traditional horse power being replaced by motorised tugs to pull those same/similar four-wheel drawbar trailers. In busy conurbations like London, you could always find short-haul examples like this and I always thought these tug and trailer outfits looked the part.

We’ve always liked what Robert Wynns did when it had the Pacific M26 converted for post-war heavy-haulage work. With crew cab and easy-access ballast box area, 192 was the first of these Wynns specials. Later, given the name of Dreadnought, it remained in service for more than 20 years.

In heavy haulage, the traction engine was long the ‘King’, and its hefty build meant it didn’t really need extra ballast to keep its wheels firmly on the ground. However, in 1929, that ‘Heavyweight crown’ was passed on when the first vehicle capable of carrying 100-ton loads was unveiled by Scammell and it, too, didn’t require any ballast as – shock, horror – it was an artic. But box-tractor lovers don’t despair as this was a one off (or actually a two off) so, while KD 9168 and BLH 21 gave more than 25 years of continuous service, the ballast-box tractors were gradually playing catch up.

In the bigger conurbations, many large concerns could find a role for the smaller, ballast-box tractor and trailer combinations on short-haul work.

Of course, the war-time years changed vehicle manufacturer’s priorities, and the civilian world had to make do with whatever it could get its hands on. A huge number of tractors were produced for the military to haul guns and battle tanks, and these were later to end up on Civvy Street. The classiest of the time was (I reckon) the imported Diamond T 980/981. Yes, while it may have the smallest, most awful driver’s cab you could inflict on what could be a three-man crew, the potential functionality of its ballast box hit the spot. Honest. Well, I say honest but, of course, I’m just an observer and have never had to climb up, sort out, get stuff down and get stuff back into this box of all sorts. How you appreciate something depends on whether you are a looker or a doer.

New in March 1958, the AEC Mandator YNN 724 must have been the most distinctive vehicle in the fleet of Westfield Transport. Regular driver Alf Mayle (seen on the left with mate Dennis Williamson), was able to do almost anything with a drawbar outfit. The AEC was saved for preservation by Alf’s grandson, Steve Mayle.

George Rotinoff was a man who was both a looker and a doer. So, when in the early ‘50s he decided to build his own massive, heavy-haulage Rotinoff Atlantics, he actually styled them on this Diamond T – albeit with a far bigger cab, And when it comes to the Rotinoff, the design of its running boards then formed a series of inbuilt steps to make the access to the ballast box as easy as pie.

When George Rotinoff decided to build his own special brand of heavy-haulage tractor, he based its creation on the Diamond T 980. However, he ensured that access to the bigger cab and the ballast box area was made a lot easier.

It helps a lot if the personnel who actually make the ballast box also have input from the people who will be using it and, when it came to transforming the Second World War Pacific M26 into a heavy-haulage tractor extraordinaire, Robert Wynn & Sons Ltd was to make a tremendous job of such a crew cab/ballast box conversion. Based in its South Wales heartland, these distinctive 6x6s were to criss-cross the UK carrying all sorts of phenomenal weights. They had to be self-sufficient so, as well as ballast weights, their massive ‘box had to carry all sorts of spares. And, being able to lift spare wheels or even spare axle parts down onto the road, or back up into the box, meant the addition of nifty hoists, as well.

The Thornycroft Antar was first built for the export market in 1950, but Chris Miller’s WHG 563V Mark 3A example was made in 1964 for the British Army. It was still in barely-used condition when bought by Chris in 1979, from the dealer GK Jackson of Morpeth in Northumberland. It did sterling work for Millers, including hauling 235 tons gross up the testing A62 over Stanedge, while enroute to the Dinorwic Power Station in North Wales.

Show regard

Before we leave the aftermath of the Second World War, we’ll make a stop off in 1945, when the most famous ‘Group of 18 box tractors’ was to make its first appearance. In certain circles, mention of the word ‘Showtrac’ is still spoken with due reverence but, back in the day, it just seemed like a good idea that the Bury St Edmunds dealer of Sidney Harrison Ltd (with its office at 26, Westley Road), would be given an exclusive to supply 18 brand new, purpose-built tractors into the showman’s world.

We’ve always liked this 1953 view of a brace of Antars which are being put through their paces by Robert Wynn. The Thornycrofts were built for the Snowy Mountain Hydro-Electric scheme in Australia but, before they were shipped Down Under, they were tried out and used to pull and push this girder trailer with a 120-ton stator on its back. Apparently, when they finished work as heavy-haulage tractors, the two Antars ended their days converted into dumpers.

At the time, with all the prevalent wartime shortages, buying one of these must have been like winning the lottery. Based on what Scammell called its ‘20 MU’ – a motive unit capable of handling 20 tons of load – what’s so surprising is how different they all eventually ended up. With the ability to travel on tarmac and – apparently – the soft of a show field with two or three trailers in tow they did, of course, carry a factory-made ballast block, and some even had a winch for self-recovery. However, also adding weight onto the axles was the presence of a huge dynamo. This meant they were self-sufficient in electric generation – via a PTO from the Scammell’s Gardner/Meadows engine – to power the showman’s rides. I’ve no idea why only 18 were built because, subsequently, many, many more ‘Showtrac’-style conversions were produced using secondhand Scammell tractor units of all ages.

When Consett-based Siddle C Cook bought the ballast-box 6×6 Scammell Contractor SPT 600 in 1955, it was an example of the biggest heavy-haulage tractor then in build. He recalled paying £7,300 for it.

There was nothing really revolutionary in the Showtrac, but snowballing all the showman’s basic requirements into one little tractor was the creation of a highly versatile package. I’m not sure when the Consett-based Siddle C Cook first cottoned on to this specialised little tractor although, in the early ‘50s, he invested heavily in three much bigger, brand new Scammell tractors. RUP 900 and 200 APT were four-wheel Mountaineers, while SPT 600 was a 6×6 crew-cab Constructor – that was then the biggest heavy haulage tractor built by Scammell. There was certainly a lot of kudos in owning such a head-turner and, while Pickfords probably had half a dozen similar 6x6s, not everyone liked dealing with this offshoot of the Government-owned British Road Services, so there was plenty of work to keep Cooky’s 6×6 (and regular driver, Walter Tomlinson) busy.

Siddle Cook was to get far better utilisation from his big Scammell once he’d converted it into an artic. And, of course, it no longer had to carry 10-15 tons of ballast every time it went out for a load.

I’m not sure when the inefficiency of heaving so much ballast weight onto this Scammell crept into Siddle’s mind but, over the passage of time, he came up with quite an idea. Of course, you need weight to ensure a box tractor keeps traction, but why not carry some (really heavy) engine/electrical generator power systems of the type used by Showmen? But, rather than use that electricity when static to power the showman’s rides, Siddle had the idea to pipe the electricity into the heavy haulage trailer. This, in turn, would have (some of) its wheels fitted with electrical motors to take that generated power and so enhance the overall propulsion/traction of his outfit. It struck me, when listening to him, that the huge plant/construction world do have a similar system, where a dumper’s engine is actually used to create electrical power which, in turn, operates compatible motors fitted to drive each of the truck’s wheels.

As I said, I don’t think anyone developed this brainwave thought of by Siddle, but he did devise something else which everyone in the heavy-haulage world was destined to copy.

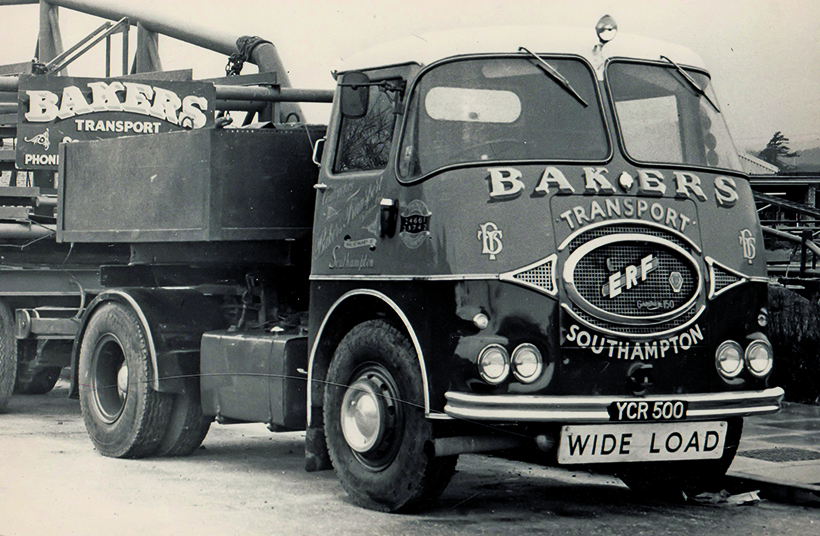

Even in black and white, it’s easy to tell how stunning the livery was that adorned the Bakers of Southampton fleet. Sadly, the temporary ballast box on this fifth wheel ERF artic unit didn’t merit the same attention.

Best of both worlds

Ballast can come in all shapes and forms and, while you could even use (a lot of) water if you wanted, steel and concrete are generally the industry’s favourites. When ordering new, an operator often specified the likes of Scammell or Foden to supply a set amount of ballast weights into the factory-made box when the vehicle was being built. And it’s still great to wander round the rally field and try to spot some of these original blocks. As time has passed, operators may have just transferred old ballast onto new vehicles or, of course, made concrete block ballast themselves to use as and when required.

During the 1960s, Atkinson was to build a variety of ballast-box tractors specifically for use by Pickfords.

The best of both worlds came into Siddle Cook’s mind when he decided to cut off the ballast box on his 6×6 Constructor and turn his vehicle into an artic. No big deal you might think, as the first 100-tonner of ’29 was, of course, an artic. But the trick is that, when a job came up that required a ballast tractor, then the original box – and its weights – could be easily craned back into position.

Of course, every modern-day heavy-haulier now has this option up his sleeve, as it’s almost the norm to spec’ vehicles both with fifth wheels (for semi-trailers) plus a drawbar trailer towing hitch for when it’s ballasted up. The bottom line is that you get two different roles for the price of one tractor, albeit with the warning of not to overload the drive axles(s) of the tractor unit when loading up your artic semi-trailer. That can be a real bone of contention.

Most ballast-box tractors had front-mounted tow hitches and air line connectors so they could turn round and push their trailers around ‘on the nose’.

I’ve no idea whether Siddle’s SPT 600 was the first biggie to do this, but the conversion wouldn’t have taken long or cost very much. Another set of air line/electrical susie connectors was needed, of course, while the driver always had to remember what sort of outfit he was controlling. When pulling a drawbar trailer, the steering geometry generally allowed the trailer to follow almost perfectly in the tractor’s wheel tracks. However, if you were hooked up to a semi-trailer – especially one with four wheels in line mounted right at the back – then those wheels could easily mount the kerb/pavement when turning any sharp corner, which could be frightening.

British Nuclear Fuels operated its flask-carriers between Sellafield and Chapelcross for something like 50 years. During the 1980s, a brace of MAN Jumbo ballast-box tractors did this work. Gross train weight was around the 94-tons mark.

The road haulage world had long championed such multiple use of its vehicles, as we related in Mike Ponsonby’s story (Heritage Commercials December 2020) when working for the Richards & Wallington crane and plant hire concern. When it was still common practice to tow all manner of assorted un-braked trailers/scrapers/power screens, Mike recalls how the company’s six-wheel Guy dumpers would always move this style of scraper round the country with – of course – a bit of spoil as ballast in the tipper’s body.

I was reminded of such efficiency during my Police days, when a colleague called me to Teesport in the late ‘70s, where an arrival from Scandinavia had caught his eye. The outfit must have weighed 80-90 tons, but the Scania 140 six-wheel rigid seemed well up for the job of shifting the nine-row drawbar trailer. The ruse the outfit was trying to pull was that, instead of being weighed down with ballast, the pulling vehicle was simply loaded with about 15 tons of general cargo. His intention was that, after delivering the abnormal load, he’d drop the empty trailer and then deliver the general cargo somewhere else in the UK.

I’ve always liked this shot of the ex-Magnaload duo (painted up in Mammoet Econofreight’s colours) toiling up the old A1 southbound at Croxdale, on a circuitous route to a paper mill in Prudhoe. There’s about 130 tons in the drum on the Scheuerle eight-row trailer. Although both vehicles were later cut up, the ballast box on the Volvo was saved and utilised for continued use.

That seemed a great idea, but this mix and match was, of course, totally illegal. And while he was allowed to deliver the load on the back of the Scania, he then had to contact the locally-based Econofreight (I think) to supply a ballast box tractor to haul the abnormal load as, without any weight on the back, the Scania couldn’t do that job.

Which is best?

It’s almost impossible to compare the virtues of a ballast box tractor in relation to one fitted with a fifth wheel, and decide which is best. However, if there was to be a vote for the best ever/most versatile ballast box tractor, then my choice would be Econofreight’s XTM 546X. Heavy-haulage devotees will be well aware of ‘The Caravan’, as it was nicknamed, and we promise we’ll come back another time to give you chapter and verse on this great servant – which is still in one piece at 40 years old.

With its ballast box incorporating three bunks and mod cons like a fridge, I reckon that XTM 546X – ‘The Caravan’ – must be the best ballast tractor you could have. We promise to cover its full story at a later time.

But, as explained, the best situation is where you can have both of these capabilities built into one vehicle, as Mike Hetherington recalls when Econofreight took delivery of six new Daf 95 6x4s in the early 1990s: “Actually, we referred to these as Dafells because they were based on the Scammell S26 design, but had the Daf cab and engine rather than a Cummins. They were a really handy motor as they came with ZF torque convertors and were rated as 200-tonners. All of them arrived as artics and Econo’ ballasted them as needed. All the ballast boxes were recycled in one form or another, and were interchangeable between the tractors. Two of the boxes started life on the ex-Magnaload F89 Volvos, and a smaller one was used first on Sunters S26 B327KVN. The ballast in them varied between 15 and 20 tonnes, and would have been the weights first owned by JD White Crane hire. After I finished in Abu Dhabi and worked for ALE in Stafford for a year, the first job I did in 2003 was in Tunisia. I could hardly believe it as the tractor they sent out to do the job for me was an old Econofreight Dafell, although that had an ALE-built box on it by then.”

Yes, the days have long gone when you could justify having a line-up of huge (Scammell perhaps) ballast box tractors sitting in the yard waiting for work as – simply put – versatility in heavy-haulage is now the name of the game. But what about in general haulage?

Mike Hetherington recalls that, in the early 1990s, Econofreight took delivery of six, very similar 6×4 artic tractor units that were used in ballast-box form as and when required. And the ballast box used in this Bill Kirsop photograph started life on an ex-Magnaload Volvo F89. Mike recalls they referred to these specific tractor units as Dafells, as they were built on similar lines to the Scammell S26, albeit with a Daf rather than a Cummins engine.

Well, you might think I’m crazy for saying that as, apart from one or two showmen who still utilise box-tractor road trains, who would want to use a ballast box tractor unit and drawbar trailer for general haulage? That’s just daft, right? Well, Lincoln-based Dick Denby for one wasn’t daft, and the time he spent poring over the law books in the 1990s produced some positive gems. So much so, Dick could operate box-tractor and trailer combinations of up to 57 tonnes gross at a time when artics were still stuck at 38/41 tonnes, all up. There was nothing illegal and, while the outfit was certainly bigger than a top weight artic, there was actually far more fee-earning payload being moved. And that included having to shift the required ballast dead weight.

Siddle C Cook would have loved what Dick thought up, and who says you could never teach an old box (tractor) some new tricks?

For a money-saving subscription to Heritage Commercials magazine, simply click here