Fascinating memories of the lime-spreading industry

Posted by Chris Graham on 21st June 2023

Alan Dale recounts his memories of the lime-spreading industry, and the now classic trucks that he and his relatives used for that work.

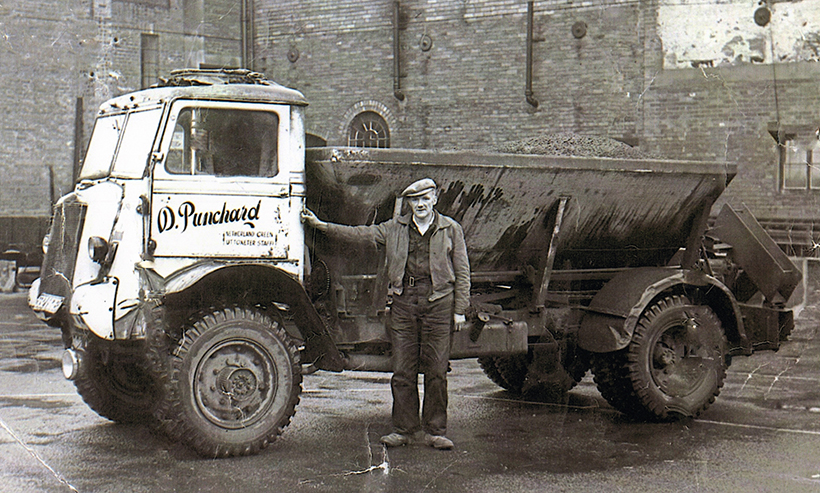

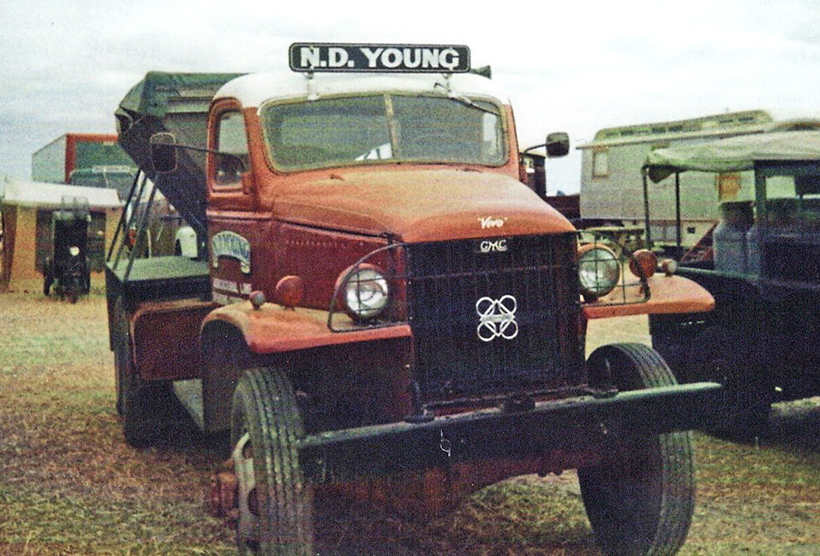

A 1951-52-registered GMC lime-spreader and my dad.

My little story begins during the last few years of the 1940s. The war had ended in 1945, leaving this fair Isle in dire financial straits. Export or Die was the government of the day’s slogan. Running right alongside the export drive was a desire – and need, actually – to feed our nation by growing the food the country required here in Britain, thus cutting down on costly importation. The government recognised that to achieve that aim, British farmers needed support in every way possible. One way that this target was furthered was the subsidisation of lime for the land and, as a result, the demand for ground limestone sky-rocketed.

I’m no farmer, however, my understanding is that ground over time can become acidic when being farmed for both arable products and grazed by livestock – I’ve heard it said that it makes the grass bitter for livestock. The ideal antidote to this acidity is lime, a calcium carbonate, or alkali. Crushed steel slag was also used which, in our area, was usually collected from Shelton Steel Works, in the Potteries.

And spreading begins, exhibition photograph, January 1957.

My dad, Frank, as a teenager was worked for a chap running a Thornycroft Sturdy. The company was engaged on farm deliveries – corn and the like – for the Stafford-based operation, Stubbs Meeson & Co. The Thornycroft was supplied new by Longton Truck Equipment, the local Potteries Thornycroft agents and had to cope with eight-ton loads according to dad, some 30% or so more than it was designed for. They also used a Vulcan which too was loaded with eight-ton payloads. Both vehicles were sold by their manufacturers as six-tonners.

Anyway, it was while dad was working out of Stubbs Meeson’s as driver’s mate on the Thornycroft that he met and got to know Doug Punchard. The two got on really well, and a bond quickly formed that would last until Doug’s untimely death in a road accident. From my own memory, Doug was energetic, enthusiastic and really hard-working; all the attributes one needs to run and build a successful haulage business.

A Bedford QL recovery truck.

Those characteristics run through the Punchard family to this day, and are evident in the several businesses run by Doug’s grandchildren. All professional, committed hauliers, running spotless well maintained vehicles, to a very high standard. It’s unclear to me now whether Doug was already a haulier in his own right, when dad and he met. However, in any event he soon was, and encouraged dad to go and work for him. They were soon lime-spreading, initially as far as I understand for and on behalf of Ballidon Quarries Ltd, which was then a small quarry, to be found near the village of Parwich, about seven miles from Ashbourne, in Derbyshire.

It was how dad met my mum, who worked in the weighbridge at Ballidon! Mum talks of dad driving Studebaker lime-spreaders back then, but the only pictures I have from that time of dad seem to show him with GMCs. As Doug’s business developed, dad was to move onto more general haulage work, from tales told long ago driving a Dennis, and then a Leyland Comet artic, before Ford Traders became dish of the day. That left a vacancy within the small company for a lime-spreader driver.

This Commer Maxiload has just finished tipping lime on the ramps.

Dad thought my grandad, (his dad) would fit the bill perfectly. Known to all, family, friends, and even my gran as ‘Pop’, my grandad had spent the greater part of his lifetime working on the land. Luckily, during the Second World War, Pop had been trained as a driver/mechanic with the North Staffs regiment, and saw action as a Bren Gun Carrier driver and, while doing so, was injured by flying shrapnel in the arm. So it was that Pop became a lime-spreader driver. He loved his time ‘spreading’ and would never tire of telling his tales about bad ‘land,’ good and bad farmers, breaking down and never leaving a ‘mess’ in the field for the rest of his life.

Initially, Pop was to use a tractor and lime-spreader. So that was a seriously outdoors job, with zero protection from the cold and rain and, of course, the shovel was king, as all the lime was shovelled off the delivering lorries into the spreader, with the arriving lorry drivers all mucking in. I recall as a small child, Pop saying to me when he was shovelling a load of lime off a lorry, to dig yourself a hole in the lime then it’s much easier going, once you have a hole to work out of.

Dan Punchard’s Foden, now more than 20 years old.

Before too long, Pop was upgraded to an ex-Army Bedford QL, fitted with a lime-spreader body. They converted the QL back axle to twin tyres and wheels, instead of the military single rear tyre and wheel, and pulled the thirsty Bedford petrol engine out, forcing into its place the economical Perkins P6. Dad said that serious cab alteration had to take place to allow the P6 to fit around the QL cab floor. I believe the main problem to be the P6 was taller and longer than the Bedford petrol and, because of the position of the front axle diff, it wasn’t an easy conversion to undertake.

As an aside, the famous Sam Longson from Chapel En Le Frith, I’m reliably informed fitted four-cylinder Gardners to many of his Bedfords, instead of the more usual Perkins conversion. The army rated the QL for three-ton loads but, after the alterations, Pop was to carry six to seven tons on his QL.

Dad with Comet Tractor Unit QL and Austin.

Pop was an extremely conscientious fella, and many times he told me that when he arrived loaded with the QL at a new field to be treated, the first thing he would do was walk the ground and, if he judged it to be a bit ‘soft’, he’d take the sheet (or tarpaulin) off the load and, after laying it on the ground, would then shovel half the load (around three tons) on top of it. He’d then spread the remaining half load with the lightened vehicle, returning to shovel the waiting half-load back on to his QL, and off he would go again. I can’t imagine many drivers today volunteering for all that extra work, and just so that the QL didn’t make a mess of the land.

Pop’s work was mainly around Warwickshire, as they were contracting for an organisation called Warwickshire Farmers. Many farmers would ask in particular for Pop to treat their land, because they had been so impressed by his care when he visited before. On the other hand, during the season the QL would be left down in Warwickshire often at night and Pop would return home with the last lorry driver to deliver lime, which was usually dad. When Pop finished his spreading for the night, then he saw it as his duty to grease round the lorry and spreader, clean the windows, and make any essential repairs. This, to dad’s great annoyance – he being in his twenties – all had to be done at breakneck speed. The two of them were like chalk and cheese really, and even in my teenage years the same stories were retold, of Pop mucking about wasting time at night when all dad wanted to do was get back home.

Lime-spreading with a tractor.

Many years later, I was told a story regarding Pop and ‘his’ QL by a member of the Punchard family, and it went something like this. One morning Pop was loaded and rolling towards Warwickshire with a six-ton load of lime on the QL. On reaching the Happy Hour Cafe at Bassetts Pole, where the A38 crosses the A453 and the A446 starts, Pop was pulled over by the law for a routine logbook and vehicle safety check. The police officer wasn’t overly impressed by the somewhat work-worn looking QL, and things become even more hostile when the ‘bobby’ felt the free play present at the steering wheel, which apparently was a full half a turn of the wheel. Pop, cool as a cucumber, drawing on his experience of Sergeant Major types in the Army, said: “Of course it’s got half a turn of play in the steering wheel, it’s been specially set like that, it’s a bloody lime-spreader.” The law wasn’t convinced!

Pop and dad with the Perkins-powered QL.

Pop continued: “Well, this vehicle has to travel on ploughed land, just you imagine what the whip would be on that steering wheel over furrows, if there was no play in the steering, it would break my wrists.” Pop was cool, confident and convincing and the somewhat crest-fallen PC’s response was: “OK, driver, on your way.”

Of course, in reality the steering was ready for a bit of attention, I don’t think today’s DVSA guys would have been so easily pacified as that Bobby was.

A model of the BRS Bedford QL lime-spreader.

In all, Pop spent around 10 years spreading lime, however, in the early 1960s my gran was becoming increasingly ill, and the long hours Pop was away from home didn’t help so, reluctantly, he left the growing Punchard operation. Mum and dad also started their own business, which didn’t involve lime-spreading.

In the late 1960s, however, dad returned as a self-employed haulier to work for Ballidon Quarries, and again resumed carrying lime to the quarry company’s own lime-spreaders. By then things had moved on a bit, and Ballidon was using Bedford ‘RLs’. Or, in my speak, four-wheel-drive ‘S’ types. I think they were running three of those, all bought new from the Bedford dealers. The shovel was still a much-used implement, but not exclusively by now as the lime-spreaders carried sets of ramps which the delivering lorry backed up, in order that the lime could be tipped directly into the lime-spreader body.

Pop and his Bedford QL.

Usually, the lime-spreader driver, after selecting a suitable spot in the field, would dig a small hole for the back wheel of his Bedford to go into, obviously making the top of the lime spreader lower, too. The ramps would be perhaps, from memory, two to two-and-a-half feet high, with a short level piece at the top, for the rear wheels of a four-wheeler to sit on, but because the ramps were quite short, the angle of ascent was acute.

In the 1990s, one lime-spreading contracting guy was still using ramps and I can confirm from my own experience that backing up these structures to attain the height necessary was ‘proper scary’. If I looked at where I was going, I always stopped short, then the ramps were so steep you couldn’t set off back any more, without cooking the clutch. I had to look only at the spreader driver directing me back to attain the correct position, and then all was well. Dad was a whizz at backing up these ramps.

Lime how it was… exhibition photo dated Jan 1957, shovelling lime.

In the late 1960s early 1970s, he had a Commer Maxiload fitted with a York third axle, plated for 22-tons gross, which meant it could legally carry just a smidge under 15 tons. However, the geometry of the axles meant that as soon as the York rear axle started the climb up the ramps, the Eaton drive axle was relieved of almost all of the weight it was carrying, and thus drive was lost. In normal, ‘off road’ conditions the York axle was configured to actual press down on the drive axle, when it ran over higher ground than the drive axle, but these ramps were so steep that the drive axle was lifted clear of the ground within a foot or so of the climb starting.

Dad’s answer to this conundrum was to reverse at speed so that the drive axle regained traction on the ramps before momentum was lost. The major skill here was to stop at the top of the ramps before the lorry’s rear trailing axle fell off the top of the ramps, with all sorts of catastrophic results on the cards, including the rear of the Commer actually in the lime-spreader body. Anyway, as far as I’m aware, that never happened, although it was something to watch. It was normal and accepted procedure for the lime-spreader driver to ‘arrow the road up’ with lime to guide the delivering lorry drivers to the fields to be treated, and this procedure worked incredibly well before the age of mobile phones. Arrows of lime would be sprinkled on the little lanes, showing left or right turns, or straight arrows if the fields were ahead. I vividly recall going with dad one Saturday morning, perhaps around 1977, after I’d become a haulier in my own right, with a load of lime, the destination being within spitting distance of Silverstone racing circuit, in Northamptonshire.

Pop lime-spreading.

There was a six-wheel ERF he was interested in buying in the Black Country, the idea being if a deal was done I would drive the ERF back. At the time he had an S39 Foden 24-ton gross eight-wheeler, a truly classic-looking motor. Anyway, we made our way up ‘Markfield’ on the M1, (between junctions 23 and 22) which fetched us down to around 25mph, with some lovely fast changes down the legendary Foden 12-speed ‘box completed as the gradient stiffened. Down past Leicester and Lutterworth, with the Gardner on song at about 52mph, and plenty of Foden vibration (I kid you not) and eventually we homed in on the field where the lime-spreader was, following his arrows.

Well we were on a tiny lane just dropping down through some trees when what looked like a long narrow branch was lying across the road. As it got closer we both realised in unison that it wasn’t a tree branch at all, it was a bloody snake, 6ft long at least, almost across the entire lane, and it wasn’t moving. I think we both just sat there for a few seconds with our mouths open, then dad said, “Go and give it a kick, Alan, see if it’ll bugger off.” I can tell you, that was never going to happen, more likely was for me to take up residency on the Foden cab roof, until it had ‘buggered off itself’.

A preserved GMC lime-spreader.

Anyway, dad eventually got brave and grabbed his shovel after jumping from the driver’s seat, arms outstretched he poked the reptile with his shovel, but it was dead and a danger to nobody. Dad scooped now no longer Hissing Sid to the side of the lane, and normal business resumed. I can only assume that it was somebody’s exotic pet, that had escaped, or had been dumped in the countryside, and had perhaps been run over by a car, after becoming lethargic with the cold.

QL still wearing its army ‘uniform’.

In the 1990s, I did a fair amount of lime to spreaders myself on behalf of a company called Croxton & Garry Ltd, which ran the fabulous Middleton Mine operation, where pure limestone was mined rather than quarried. This mine is massive, sadly closed now, however, huge dumpers ran backwards and forwards within. The ground limestone (which was so fine it ran like water in the lorry body) stockpile was actually inside the mine and, to be loaded, lorries had to go inside the mine, turn right at the third addict, and then drop down almost underneath the haul road the big dumpers were travelling. It was a truly amazing experience, especially on a hot day, when underground it was so much cooler.

Sad to see, the entrance to Middleton mine, photographed in 2022.

By this time, the majority of the lime delivered to the fields was tipped by the lorries in the field, the spreading contractors picking it back up again with Hiab-type grabs, with the exception of the one guy mentioned above still using ramps. Most of the lime Croxton & Garry supplied was delivered to the Staffordshire and Shropshire rural areas, the busiest period being from perhaps August to when the ground got so wet nothing could travel on it, around the end of October or so.

Steetley’s idea to save labour in the field.

I loved the work actually, there wasn’t any time constraints, no deadlines to meet, such a relaxed environment to work in. It was by no means unusual to load for Market Drayton or similar and get to the farm at five or six a clock at night, the farmer to give you directions to the field, and off you go, master of your own destiny, nobody else to please but yourself. The farmers by and large were very helpful, the biggest danger being getting bogged in a soft field, or worse ‘catching’ a gate post when travelling through a narrow slippy gateway. I always carried a ‘D’ link and chain, and there was always a tractor to extract you from your dilemma.

The business end of the GMC.

This feature comes from the latest issue of Heritage Commercials, and you can get a money-saving subscription to this magazine simply by clicking HERE

Previous Post

TS Queen Mary benefits from £1 million donation

Next Post

1920s Dennis ‘pirate’ bus superbly restored