Sterling’s intriguing and ground-breaking trucks

Posted by Chris Graham on 22nd February 2022

Sterling produced a variety of intriguing and ground-breaking trucks between 1907 and 1953, as Ed Burrows explains.

Intriguing and ground-breaking trucks: With other trucks providing retardation force at the rear, a chain-drive Sterling eases a 70ft long 16in naval gun down a six percent gradient on its way to installation in 1939 as part of San Francisco’s Second World War coastal defences. Heavy-lift contractor Bigge is still in business.

Its trucks featured all-bolted, steel channel section chassis with seasoned oak inlays. It stuck with the traction advantages chain-drive – and was the first to exceed 500-bhp. The make was Sterling. Unsurprisingly, in its peak decades, it enjoyed a reputation as the ultimate go-to US-make for engineering integrity and rugged quality. Although takeover in the early 1950s resulted in it being retired to the Old Timers’ Hall of Fame, the make carried sufficient weight for a short-lived revival starting during the second half of the 1990s.

In the beginning, the trucks were badged Sternberg. Founded in 1907 by William Sternberg in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, in 1915 the name was changed in deference to growing anti-German sentiment in America even before US armed forces joined the fight in the First World War. In 1918, it became one of 15 manufacturers to build Gramm-Bernstein designed ‘Liberty’ trucks for the US Army. By the war’s end in November of the same year, it had delivered a total of 479 ‘Liberty’ model Bs.

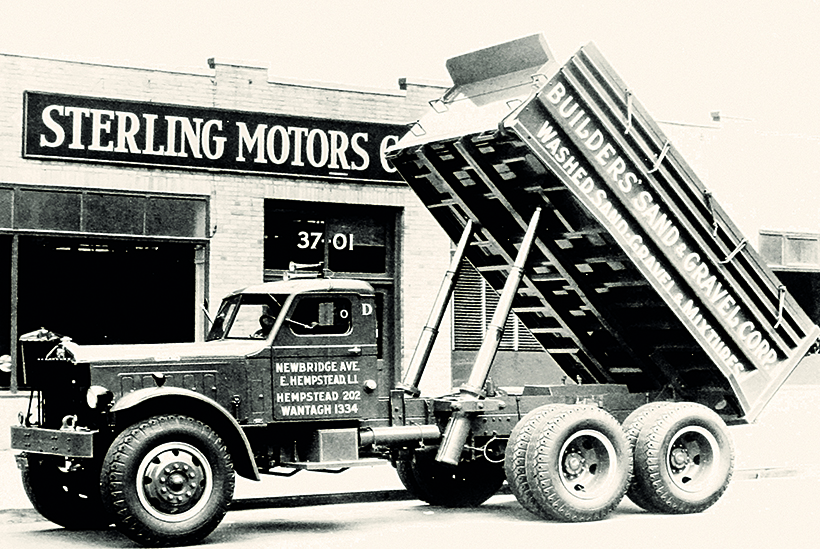

Early 1920s Sterling on solid tyres. Due to their proneness of punctures, pneumatics did not become the exclusive tyre fit until the early 1930s.

The early trucks were forward control, with capacity ratings between one and five tons. (Tons here are 2,000-lb US short tons, as distinct from the 2,240-lb of British ‘imperial’ tons).

Top of the range models had chain-drive. Specifications lower down the weight scale had worm drive. A total switch from forward- to normal-control was made in 1915, and the weight range extended upwards to a capacity of seven tons.

Unlike the riveted construction used by most other manufacturers, chassis were bolted throughout. The timber inlays minimised metal-to-metal contact, reduced frame distortion and absorbed road shock. All-bolted assembly was designed to overcome the proneness of rivets to work loose or shear. The concept was highly effective and patented by Sterling in 1922. This helps to explain why the technique was not adopted by other manufacturers. Timber laminated chassis continued to be the make’s signature feature until Sterling was killed off in 1953 following takeover by White in 1951.

Lighter Sterlings were variously produced with chain or propshaft/worm drive. As the 1930s progressed, concentration switched solely to heavier models.

Prior to introducing six-cylinder engines for heavier models in 1928, Sterlings used the company’s own four-cylinder gasoline units, the cylinder blocks of which were cast in pairs. The four-cylinder range was produced in three series. Models up to 2.5 tons had four-speed sliding gear transmissions, whilst 3.5- and 5-tonners had three-speed constant mesh transmissions. Both these ranges were available with propshaft/worm-drive or chain-drive. The 5- and 7-ton trucks – together with their 12- and 20-ton capacity semi-trailer tractor counterparts – had constant mesh six-speed gearboxes (and were chain-drive only). By this time, Sterling was also producing twin-axle back ends.

From the mid-1920s, most weights were available with the choice of worm- or chain-drive, although for heavier specs – which became Sterling’s exclusive focus during the course of the 1930s – chain-drive was the norm. The key factor here was the company becoming an early adopter of Waukesha’s new 12.8-litre six-cylinder gasoline engine. This developed 186bhp at 2,100rpm – impressive numbers for a non-diesel. Introduced in 1930 – and coinciding with the almost total abandonment of solid tyres as an option – the Waukesha was the highest output truck engine produced in the US up to that time. At the heavy truck end of the market, it propelled Sterling to king of the hill status.

A beautifully-restored, late 1930s chain-drive twin bogie heavy tractor restored by Joseph Equipment, which specialises in new and classic truck sales.

Reflecting new legislation governing vehicle lengths and weights, in 1935, Sterling reintroduced a forward-control option (cabover, in US parlance). The configuration allowed a longer loadbed in rigid chassis guise – and enabled tractor units to couple a longer semi-trailer. Sterling’s all-new two-axle GD195 semi-trailer tractor featured an 11-litre Cummins diesel as standard, with the option of Waukesha gasoline units. Way ahead of its time, its standout, feature was a tilt cab – but like no other tilt cab since.

The front panel, with sloped ‘V’ windscreen and angled quarter windows, remained fixed. For engine access, the main structure – comprising back-panel, sides and roof – tilted rearwards on hinges at the back-panel’s base. Clever – but superseded two years later by a replacement that tilted forwards in manner subsequently copied by others. The standard engine of the revised G series launched in 1937 was a 125bhp Cummins. Specifications spanned rigid trucks, tractors and tandem rear axles.

If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it: as this rear end view shows, chains don’t look too robust – but in Sterlings case, don’t be deceived by appearances.

Credit where it’s due: although Sterling ceased to be before it could properly exploit its tilt cab models, it was a definite pioneer of the trend that led cabovers to become the most popular configuration for US ‘big rig’ heavies over the 1950-1980s period.

In 1939, Sterling acquired the assets of Oakland, California-based Fageol, which had ceased trading. The manufacturing assets were sold on to T.A. Peterman, who reformed the operation to create Peterbilt truck business. Astutely however, Sterling retained the former Fageol-owned sales network. This gave Milwaukee-based Sterling a presence on the western side of the US, which proved receptive to the company’s higher-powered Waukesha and Cummins models for over-the-highway haulage and the rigours of logging.

Sterling ended the 1930s with the introduction of an all-new V-windscreen cab for its normal control models. This replaced the one-piece flat glass windscreen cabs fitted for the previous 20 or so years.

Belying the size of the drive sprocket, Sterling’s Super Traction chain-drive system handled the 186bhp of a 12.8-litre Waukesha gasoline engine with dependable ease.

The new two-piece windscreen cab was fitted to two distinct model ranges, both characterised by noticeably long engine hoods. The heavier H models had an impressively massive traditional cast radiator shell – and their standard specs were chain-drive. The lighter J models had dual- or single-axle propshaft transmission with worm-drive diffs. They were distinguished by an ornate sloped-back radiator grille similar to the style typical of American automobiles of the period.

In double-drive bogie tractor form, J models had a maximum combined gross of 34 tons. Specs were available with either diesel or gasoline engines. Although weight-saving alloys were used for parts that were not subject to severe stress, the channel-section chassis main members continued to be seasoned-oak lined in Sterling’s time-honoured manner.

Sterling’s biggest Super Traction drive wreckers were 40 tonners, principally used by the US Navy for clearing crashed or wrecked aircraft.

In continuing with the use of chain-drive for its heavy-duty twin-axle bogie H models, Sterling promoted the system as Super Traction. While one might question the efficacy of what might appear to be an infernally complicated final drive arrangement, in practice, the system combined extreme reliability with exemplary agility. Power was delivered individually to each wheel’s drive chain by a combination of three limited-slip differentials and concentric jackshafts. The transmission system ingeniously functioned in synch with the inverted semi-elliptic spring and radius rod suspension setup. When operating off-highway, the Super Traction system automatically directed power away from any wheel tending to spin though lack of traction. It compensated for this by delivering maximum power to the wheels with most grip. On surfaced highways, the Sterling Super Traction system had the additional benefit of reducing rolling resistance due to power-sapping tyre scrub.

The Second World War brought contracts for special types for service with the US military, and principally the Navy. Production was largely concentrated on Waukesha powered 7.5- and 10-ton shaft-drive 6x6s, variously equipped as wreckers for clearing crashed or damaged aircraft from runways or with airfield fire crash apparatus.

To counterbalance the Gar Wood crane lifting at maximum reach, the 6×4 Sterling HCS 330 was fitted with massive steel plates at the front of the vehicle.

Biggest of all were 40-ton gross model HCS 330 6x4s fitted long fixed-boom Gar Wood cranes, again chiefly used for lifting crashed or damaged aircraft. The specification included a six-cylinder, 186bhp Waukesha gasoline engine and tandem rear chain-drive, together with Fuller main gearbox and auxiliary transmission system that combined to provide twelve forward speeds.

Massive 14.00x24s tyres dwarfed the cab and engine hood sheet-metal. The front-end was heavily ballasted to counterbalance the Gar Wood’s long-reach boom.

In terms of power, in US Second World War military wheeled vehicle inventories, Sterling HCS 330s were second only to the US Army’s 240bhp Hall Scott engined Pacific M26 ‘Dragon Wagon’ tank transporters.

Interesting as Sterling’s maverick approach to truck engineering was to this point in its history – you ain’t seen nothing yet…

Towards the end of the Second World War, US Army planners became greatly exercised by the problem of underpowered wheeled transportation assets, particularly at the heavy end of the spectrum.

Second World War military production comprised chain-drive 6x4s and propshaft drive chassis like this 6×6. They operated as either wrecking cranes or as airfield fire crash tenders.

With its record for delivering ultra-dependable special-duty heavy vehicles under its belt, in 1944, Sterling was awarded a prototype development contract for a 12-ton rated heavy truck designated the T26. It was arguably the world’s first-ever heavy 8×8, and the first truck with more than 250bhp. No less remarkable than the vehicle itself, it was designed, built and delivered within the space of nine months.

On paper, the T26’s technically ambitious combination of propshaft and chain-drive transmission to all eight wheels and high-articulation suspension made the concept appear complex in the extreme. But thanks to an alliance between an inspirational project manager, US Army Lieutenant Hodges, and Sterling’s engineering team, the concept not only worked, the mobility demonstrated by the T26 in proving trails set new performance benchmarks for wheeled heavy all-terrain trucks.

The project straddled a time when US Army planners were bitten by the bigger-is-better bug. Momentum was propelled by the emergence of heavier next-generation tanks, primarily the 70-ton T29 and the turretless 95-ton T-28/T-95, designed to out-fight Nazi Tiger IIs. The problem was, the US Army’s M26 ‘Dragon Wagon’ was designed for hauling tanks and material weighing a maximum of 40 tons.

Just prior to the Second World war, Sterling replaced its long-serving flat windscreen cabs with an all-new ‘V’ design, but retained cycle-style fenders and traditional cast radiator shell.

After peace broke out in 1945, programmes like the T26 began to be wound down. But as might be expected, a lot of US Department of Defence folk were having so much fun with their big boys’ toys experiments they fought a rear-guard action to prevent development being terminated. But eventual surrender was inevitable. In 1947, the axe fell on the overall T26 programme – which also embraced the Cook Bros. eight-ton rated wagon-steer T20 and T20E1 8x8s, the Corbitt T33 and T33E1 8x8s – which had conventional steering and transmission – and the Sterling T28, T29, T35 and T46 (of which more anon).

Mechanically, the T26 was distinctive in the extreme. Chain-drive all round was not even the half of it. The tandem front axles were mounted on a turntable platform bogie, with steering operated in the manner of a drawbar trailer with a pivoting front axle arrangement. To accommodate the front bogie, the chassis was of stepped-frame, swan neck configuration. Tyres were 20-ply 14.00-24s, with duals at the rear and fitted either as singles or duals at the front. Suspension all round was by inverted semi-elliptics.

Lighter J models featuring an automobile style grille and fulsome fenders were exclusively propshaft/worm-drive diff transmission, with single axle or dual-drive back ends.

The nine-metre long T26 was powered by a 12.3-litre, 275bhp American LaFrance V12 petrol engine with a torque maximum of 562-lb.ft at 2,000rpm. Power was transmitted via a twin-plate clutch, five-speed main gearbox, two-speed auxiliary box and two-speed transfer box. With the 17.03 to 1 ratio of the drive chains, the overall transmission system gave lowest drive ratio of a stop-at-nothing 373 to 1. Small wonder in a test involving travelling through a mud pit, equipped with dual tyres front and rear (which themselves were fitted with grouser-type wheel-pair traction devices), the T26 was able to complete the course ahead of an M6 tracked high speed artillery tractor. (For expedience, the T26 was fitted with a tracked high speed tractor type cab).

The T26 was trialled in both cargo truck and fifth-wheel tank transporter tractor guises. In the latter form, it was capable of a gross train weight of 90 tons. The maximum road speed was an impressive 35mph and gradeability in low range was theoretically 110 degrees. Thanks to the high mounting of the engine resulting from the elevated front section of the swan neck chassis, the maximum fording depth was in excess of five feet.

But even bigger things were to come

The T26 truck and tractor trials vehicles were so successful that shortly after the Second World War ended, Sterling was awarded a follow-on contract for a series of further 8×8 developments, the T26E1 cargo truck and T26E3 fifth wheel prime mover – with an unladen weight of 28 tons – and the gargantuan T26E2 wrecker. Equipped with a Gar Wood single boom crane, at maximum boom retraction the T26E2 was capable of lifting 17.5 tons.

Sterling was a pioneer of forward-control trucks with tilt cabs. G models like this were introduced in 1937. They replaced the design introduced two years earlier which had a fixed front panel but rearwards tilting doors, roof and back panel structure.

The swan neck chassis/super Traction transmission T26Es were powered by Ford V8 GAA 18-litre, 525bhp DOHC petrol engines that otherwise powered tanks. The follow-on trucks differed from the earlier T26 in having a front-end incorporating a full width engine hood ahead of a soft-top driving compartment. Research suggests these were the first ever trucks to exceed 500 horsepower.

The apparent gung-ho, size-is-everything attitude of US Army planners led to further Sterling contracts for as series of experimental 6x6s, with a front-end similar in appearance to the T26E trucks. The baby of the bunch was the 290bhp, eight-ton payload rated T28. Its bigger siblings, both built in 1947 as fifth wheel prime movers, were the 20-ton rated T29, powered by Ford’s GAA V8 tank engine, and the 770bhp, 25-ton rated T35. That’s worth repeating. 770bhp: monstrous even by today’s standards. The T35 had a 27-litre Ford GAC V12 petrol engine (from which the GAA V8 was derived). The design of the Ford GAC was reputedly influenced by the Rolls-Royce V12 Merlin aero engine.

With rear and turntable mounted front chain-drive bogies, the ultra-radical 1944 Sterling T26 performed with unprecedented agility. With 275bhp, it was more powerful than any previous wheeled vehicle.

The T26, T28, T29 and T35 might convey the impression that Sterling was on a roll. In reality, the business was on a hiding to nothing. Awesome as they were, the experimental US Army 8x8s and 6x6s did not mature into production vehicles, which helped precipitate the company’s short-lived existence after White’s takeover in 1951.

Discontinuation of the Sterling make in 1953 was influenced by the fact that new owner White had secured a deal under which it sold and serviced Freightliner trucks. Also, Autocar had become part of the White stable. Sterling and Autocar products more or less paralleled each other. Result: Sterling, with declining sales at that time, was the one selected for the chop. Between 1907 and its closure, a total of some 12,000 trucks rolled out Sterling’s Milwaukee, Wisconsin, manufacturing facilities.

Few trucks for the civilian market were produced during the Second World War. Built in 1944, this preserved H series Sterling is a rare exception.

History is full of perverse twists and interlocking loops. In 1997, Freightliner acquired Ford Motor Company’s heavy truck division. To re-badge the trucks, in a deal with Volvo, which by then owned White, Freightliner revived the Sterling name. Fast forward a dozen years. Sterling trucks again ceased to roll off the assembly lines, shut down this time by Freightliner’s parent – Daimler AG (aka Mercedes-Benz) in response to the 2008-2009 global financial meltdown.

Freightliner-era Sterlings comprised two heavy series with set-back front axles, one with set-forward axles and a medium duty range. Rigid specs grossed up to 36 tons, tractors up to 53 tons, and engine options included Mercedes, Detroit Diesel, CAT and Cummins units with outputs from190- to 550bhp.

The US Army’s big boys’ toys T26 experiments culminated in the scaled down 1948 E28, a 6×6 with Super Traction drive. It did not proceed to production.

Anyhow – there you have it. Sterling trucks. Oak-lined and bolted. And in the annals of automotive history vastly more interesting than the 1987-1991 Rovers that were re-badged as Sterlings – the Austin-Morris-MG-Jaguar-Triumph-Rover conglomerate’s last throw of the dice in its failed attempt to reverse its declining exports to the US.

For a money-saving subscription to Heritage Commercials, simply click HERE