The AEC story

Posted by Chris Graham on 8th March 2020

Malcolm Bates tell the AEC story using many, previously unpublished photographs of its lorries, from the Southall factory files and major distributor, Oswald Tillotson, in association with the Motoring Memories Heritage Museum of Ballygowan, N Ireland.

The AEC story: Here’s a great photo of an AEC Mammoth dropsider operated by transport contractor, HA Newport of Fordham, Cambridgeshire. Judging by the conveyor and the pile of stone in the foreground, it looks to have been delivering sacks of cement to a building site but, in fact, this was the site of a tram track relaying operation in Wood Green, London. The year was 1932 and, amazingly, the same Newport family is still in the road transport business today, as Newport Bus.

Love it, or hate it, that famous, triangular AEC logo has been fixed to the radiator of many iconic commercial vehicles, ranging from some of the very first ‘own brand’ diesel-engined bus chassis and the ground-breaking ‘Q-Type’ of the 1930s, to the ubiquitous RT and Routemaster of the post-war years.

But what about the lorries manufactured by ‘The Builder of London’s Buses’? One minute they were being exported to just about every country on earth. The next, they were being plastered with the corporate ‘Flying Plughole’ logo of arch-rival, Leyland. How did that happen?

Unanswered questions

You could spend a lifetime trawling through period transport magazines for answers to that question, and still not find any detailed explanation. In fact, dig a great pile of contemporary transport publications out of any archive (as I recently have), and the lack of any credible reason just makes the ‘merger’ of Leyland and AEC in 1962 seem even more… well, odd. True, there was much talk about ‘pooling of resources’, to help ensure British products had more support overseas, and that our impending membership of the ‘Common Market’ was a success, but…

Although this print is sadly damaged, it’s a great shot that could indeed be ‘period’ but, in fact, isn’t! The post-war Triumph motorcycles in the foreground give the game away. This AEC dropsider and dropside trailer, in W Marshall of Andover colours, wasn’t photographed in the mid-1930s, but during the HCVS London to Brighton run in 1994, according to the original caption.

Had it been a genuine ‘merger’, of course, things might have been different. But, aside from a few bland and meaningless statements by AEC chairman, William Black, such as: “No existing AEC models would cease production.” But that promise didn’t last, once Lord Stokes moved his troops in. The merger did nothing to address what the future would look like with two equally large manufacturers producing previously competitive ranges of lorries and buses on a model-by-model basis.

This all suggests that the ‘merger’ was either influenced by government intervention (something that was never suggested), that it was instigated by a secret acquisition of AEC shares by Leyland (quite possible), or that there was some disaster at AEC that caused the directors to panic and go cap-in-hand to Leyland for talks.

The commercial vehicle world is after all, a very incestuous place and the senior personal of any manufacturer would have been on first name terms with most of the competition. Equally, most component suppliers will have had close relationships with several chassis manufacturers. So, if you ever wanted to find out a secret about your competitor, a visiting sales rep would be the ideal person to ask over a drink at the golf club, old boy!

Here’s another pre-war AEC that has somehow survived into preservation, although after a flurry of activity, it hasn’t been seen for a while. It’s a real rare bird too, being a normal control Mammoth Minor, with single-tyred rear axle, in much the same vein as modern Scanias and Volvo 6x2s. It was photographed having completed the HCVS Trans Pennine Run by A C Peacock for the Stevens Stratten Archive.

Confidence running high

But looking back at the rise – and fall – of AEC with 20-20 hindsight, what stands out is that there’s no hint in the press of AEC being in financial trouble, either up to, during or after the merger. Both sales and profits were up, and confidence in the future was high. Although, as the fall of Guy Motors will remind us, the true state of the company accounts don’t always reveal everything publicly at the time.

Like Guy (and, indeed, ERF and Foden), AEC directors had seemingly invested heavily in setting-up overseas manufacturing facilities or, in other cases, taken a financial interest in foreign manufacturers, such as Willeme, in France. Arch-rival Leyland was doing the same, of course, but there was surely every reason to think that the world was a big enough place for Leyland and AEC to co-exist, in the same way that Mercedes and MAN, or Scania and Volvo have managed to in more recent years.

But, even if that was the case, we need to dial-in the fact that Leyland directors would have had detailed knowledge of AEC accounts, as a result of the BUT joint venture company that both manufacturers had formed in 1948, to produce trolleybuses and diesel railcars. But that only poses even more questions. Like if BUT worked so well, with the two companies co-operating together as equal partners, why wasn’t it possible to, say, restructure the ‘ACV Group’ to promote the collective sale of AEC and Leyland (and of course Scammell, Albion and Thornycroft) commercial vehicles in global markets, without a corporate ‘merger’?

This, normal control AEC, features in a period factory shot of a Monarch fitted with a demountable furniture removals container, operated by Curtiss & Sons, of Southampton. ‘Special attention has been paid to providing good visibility for the driver…’ we’re told. In other words, the cab has larger-than-normal windows!

It’s a question that, the more you think about it, the more you wonder why it wasn’t the solution. And it makes you wonder (or at least, it makes me wonder) what the future of both AEC and Leyland would have looked like if they had stayed arch-rivals?

A merger or not?

The AEC-Leyland ‘merger’ was, of course, no such thing. It was a takeover, pure and simple. And that brings us to the point where the good and bad aspects of one company over another, tend to get compared. The vehicle range was almost exactly comparable, model-on-model. Except there was a glaring gap in the AEC passenger vehicle range in the early 1960s – a total lack of rear-engined, double-decker chassis. Which poses another question – how come? Especially as AEC engineers had already helped the Canadian Car Company (CCC) produce a transverse-engined single deck ‘transit bus’ for the North American market, confirming that a suitable drive train already existed. Plus, there was the heritage of the side-engined Q-Type.

But then, as it was hardly a commercial success, perhaps that was the reason why AEC directors didn’t sanction an advanced Atlantean rival? Even so, it appears to have been a remarkable blunder by AEC directors to have not taken into account the ramifications of the Bus Grant (promoting OMO double-deckers) coming in during the 1970s, doesn’t it?

For sheer road ‘presence’, there are few pre-war lorries that can top this 1932 Mammoth insulated box van, operated by Hay’s Wharf. It’s been seen before, but that unusual ‘Hygienic Meat Conveyance’ body, with recessed spare wheel – being fitted with a large low-pressure ‘balloon’ tyre, it wouldn’t fit under the chassis – is well worth closer study. And it makes an interesting contrast to the horse-drawn van parked behind it.

But it was on the lorry front that the greatest contrast existed, for all to see. On the one hand, the cabs fitted to AEC Mammoth Major MkVs were among the prettiest of any lorry cab of the era. But on the other? We’re not talking about a ‘proper’, all-steel, pressed cab like those available on Leylands, Bedfords, or even BMCs. Besides, the cabs fitted to AEC goods vehicles weren’t even produced in-house.

True, many were made by fellow ACV Group member, Park Royal Vehicles but, for whatever reason, those setting marketing policy at AEC seemed to resolutely hold the view that a lorry cab was a trifling, minor detail to be determined in the latter stages of a deal between the customer and the local AEC dealer. Not as a vitally important piece of marketing strategy, that could not only determine the long-term operational life of the chassis, but also the life of the driver in the event of an accident and, indeed, the ‘brand image’ of the end-product itself.

This AEC helps illustrate the sheer diversity of chassis that came out of Southall. It’s a special, drop-well machinery transporter designed specifically for Pickfords, in 1936. Based on the then-still-new Mammoth Major eight-wheeled chassis, it was christened ‘The Crocodile’, and was one of three built.

The cab debate

But, while the comfort and safety of the driver seldom seemed to be discussed in the 1930s (when most lorry manufacturers bought-in cabs made by a third party), from the mid-1950s on, drivers’ opinions on the suitability of their workplace started to play an increasing part in the purchase decision of many organisations. More to the point, the all-steel cabs fitted to German and Scandinavian (and Italian) lorries, tended to feature cabs with not only more comfort and safety, but better heating and ventilation systems as well.

In overseas markets, they were competing head-to-head with British chassis, fitted with cabs made out of fibreglass, aluminium and wood framing. A decent heater/demister was still just a distant dream. While only a few journalists on ‘The Commercial Motor’ voiced concerns that British commercial vehicles were falling behind at the time, those same well-equipped foreigners would soon be competing directly in the UK market as well, just as predicted.

So, could the urgent need for an new all-steel tilt cab have been the expensive stumbling block that led to AEC directors seeking a shotgun wedding with Leyland? Could the mounting cost of designing and producing an all-steel, pressed cab have been a project that the elderly directors (with memories of drivers having no more than a windscreen and an old sack to keep them warm) simply refused to sanction? For perspective we need to note that the cost of tooling-up production of the MGB in 1962, was said to be over £500,000, at a time when a new lorry chassis cost about £1,200.

This is rare photo of an early Mammoth Major eight-wheeler – the very oldest in existence, we’re told. That’s ‘rare’ because it’s an exhibit owned by our National Science Museum. In other words, it ‘belongs’ to all of us. So why, you may wonder, does it spend its life locked away in an aircraft hanger, so none of us can see it without an appointment? A good question.

Who designed the Ergomatic cab?

Here’s an interesting ‘conspiracy theory’, for you. Look more closely at the ‘Leyland’ Ergomatic cab. Was it really a Leyland design, as publicity at the time had it? Are you sure? Look at the space for the logo under the front screen. Notice how on AEC-badged models, the angles all match the logo. Now look at a Leyland-badged Ergo, where they don’t. In fact, the ‘Leyland’ name seems to have been wedged into a space that was never designed to take it.

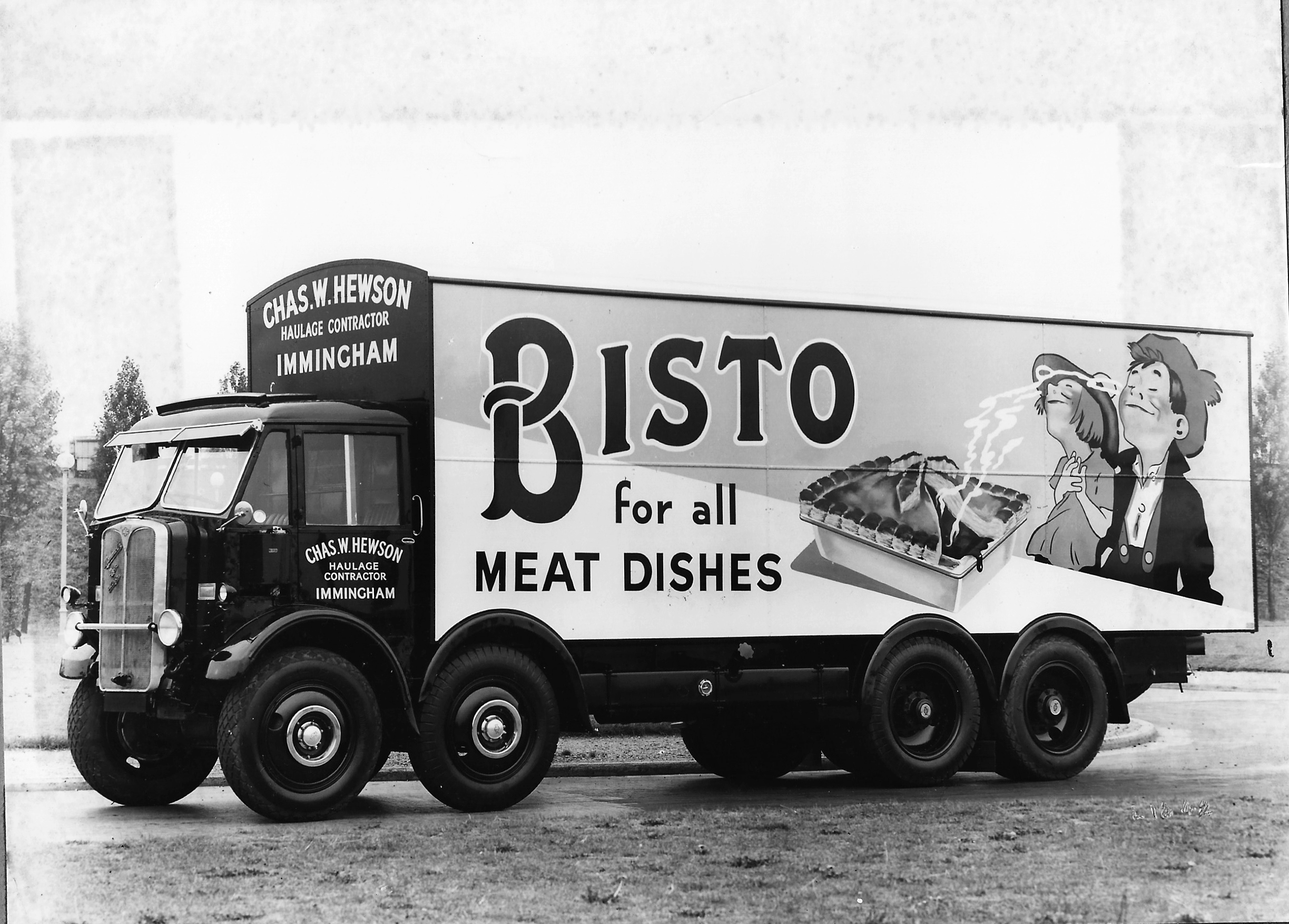

Aah, Bisto! Quite whether this Mammoth Major was loaded-to-the-gunnels with the famous stock cubes, we can’t confirm. But wouldn’t it look great restored and in original colours on today’s roads? Note the driver’s cab has some interesting features, including glazed exterior sun visors and, by the looks of it, a sliding sunroof. A luxury cab on an AEC?

In contrast, the ‘A-E-C’ lettering looks fine in that lower grille, doesn’t it? Like it was designed specifically for it, in fact. So, could the Ergo cab have originally been designed by AEC (no single designer’s name is credited in the launch publicity) but then, thanks to mounting costs (or bottling-out by the old-guard directors), the project stalled until Leyland got to hear about it? AEC – The Lorries from Southallexplores that time line.

The AEC that won World War II? Well, maybe. The trusty Matador was so tough, many went on to act as breakdown lorries for decades after VE Day. In fact, quite a few are still in service today! Most were 4x4s but this one, photographed by Steve Greenaway, seems to have grown a third axle.

Or was it simply the fact that AEC marketing was falling behind in terms of spend and effectiveness? Ironically, although The Leyland Motors Group (before it became bogged-down with the politics of British Leyland), was much more marketing-orientated than AEC (and already had all-steel cabs, of course), Leyland didn’t survive that much longer as a manufacturer of lorries and buses on the global stage after the AEC take-over did it?

Originally a foam tender at Esso’s Fawley Refinery (a regular run for Xzit (GB) Limited’s Commer QX box van during the author’s formative years), this smart Mammoth Major was still in use in 1990, when photographed by Steve Greenaway for the Stevens-Stratten Archive.

The final irony? DAF, the one-time Dutch manufacturer of horse-drawn farmers’ carts and lorry bodywork, owed its future to Leyland, as the supplier of diesel engines for a new lorry range. Yet, once in control of ‘Leyland DAF’, DAF management went on to rip Leyland to pieces. AEC killed-off Maudslay. Leyland killed-off AEC. In turn, DAF killed-off Leyland. Who says the commercial vehicle world is a friendly place to forge a career?

Bowyers, of sausage and pork pie fame, was one of many household names that entrusted in-house transport and distribution to a fleet of AEC lorries. Here, we see AEC Mercury, 287 CMW, photographed by the official AEC photographer for possible use in a press release as a follow-up to an article on the company in The AEC Gazette. The parked cars include an original Vauxhall F Series Victor (complete with bonkers exhaust pipes exiting from inside the over-riders) and a Mk 3 Zephyr. Passing in the opposite direction is the widest car then built in Great Britain, the Mk 10 Jaguar (for younger readers, that’s almost the same width as a modern so-called BMW ‘Mini’). Parked by the kerbside is what could well have been the photographer’s own Vauxhall HA Viva. A ‘vintage roadscene’ indeed!

The bottom line? More than 50 years after the Leyland takeover, the story of AEC still poses unanswered questions. But never mind all that, thanks to the generous co-operation of Raymond Walls of the Motoring Memories Heritage Museum of Ballygowan in Northern Ireland, AEC – The Lorries From Southall is packed with hundreds of stunning archive photographs of AEC lorries from the very first, through the 1930s, ’40s and ’50s, to the ‘Ergo’ era and some of the last examples to be built at the Southall factory before it was closed by Leyland. Many have not been seen in print before.

An interesting pair of AECs in preservation. NTM 744 (left) is a Mercury built in 1954, while 680 GTM is a Mercury Mk II, built in 1962. According to Peter Quinn (who took the photograph for the Stevens-Stratten Archive), this was one of 41 Mercurys fitted with air suspension.

You can subscribe to Vintage Roadscene magazine by clicking here