The history of Tata

Posted by Chris Graham on 4th May 2020

Ed Burrows delves into the history of Tata, which began life in 1954, as a Mercedes-Benz joint-venture.

The History of Tate: Tata Motors grew out of a 1954 joint-venture with Mercedes-Benz. The three-pointed star was replaced with the ‘T’ emblem when the JV ended.

Images: Rupert E Burrows, Tata Motors

From the beginning of this year, the Indian Government imposed a life cap of 20 years on commercial vehicles. This will make a big dent in old truck restoration in India – though, in this case, restoration has been to keep on trucking, as opposed to collectors saving classics for posterity.

The net effect will be to help manufacturers like Tata Motors, India’s biggest (and second biggest in the world when the lightest models are included). With an output running at around 180,000 units a year, Tata has over 40% of the country’s medium and heavy commercial vehicle market.

Tata strengths

So, what is Tata? Well, aside from Tata Motors being India’s fifth biggest company, Tata Steel is the ninth biggest, Tata Consultancy is the 11th biggest and Tata Power is the 43rd. But the group has many more constituent businesses than that. As well as being India’s largest conglomerate, Tata is the biggest overseas-owned industrial employer in Britain. It has had business interests here since 1907, the best known of which today is Jaguar Land Rover. And we can’t overlook Tetley Tea, part of a Tata business that ranks as the world’s second biggest tea producer. Anyone for a cuppa Tata?

Pedigree? You can say that again. Admittedly, the picture isn’t so rosy at the moment but, with remarkable speed – in 2008 – Tata rescued and re-energised Jaguar and Land Rover from the moribund state they were in at the time Ford cut its losses and sold out. As testimony to the quality of Tata’s management leadership, within four years of the takeover, Jaguar Land Rover turned in a profit of £1.7 billion. Deal or no deal? Damned near deal of the century. The fourth year profit was not far off £600 million more than Tata paid to take Jaguar and Land Rover off Ford’s hands.

A veteran, DIY-cabbed Tata 1210 12-tonner, quite similar to the original licence-built Mercedes model.

‘British-made’ used to stand for something – it was once a globally-respected hallmark of quality. Jaguar Land Rover is more than doing its bit to restore the country’s manufacturing reputation and industrial pride. With that essentially down to Tata, it’s a fair indication that, when it comes to trucks, in Tata’s case, ‘Made in India’ signifies quality in the sense of both the products and the business that stands behind them.

In entering the commercial vehicle business, Tata gave itself a head-start. Its commercial vehicle manufacturing activities began in 1954, on the back of a 15-year collaborative agreement for the production in India of Mercedes-Benz-designed, bonneted, medium trucks. In 1971, by which time the operation can be said to have reached engineering maturity, the Mercedes-Benz three-pointed star came off and, since then, radiator grilles have proudly featured the ‘T’ emblem.

In the beginning

The enterprise that’s grown into the Tata Group of today – embracing over 80 different businesses with interests ranging from salt to software – began life as a trading company founded in 1868, by Jamsetji Nusserwanji Tata. The reins of the family dynasty passed to Ratan Tata in 1991, and he finally stood down as head of the group in 2017. With a Harvard education tempered by a stint as a blast-furnace labourer at Tata’s Jamshedpur steelworks behind him, group patriarch Ratan Tata’s guidance of the flourishing empire over recent decades has been marked by a combination of entrepreneurial vision and feet planted firmly on the ground. Under his tutelage, the group seized opportunities created by India’s economic liberalisation that took place during the 1990s. The group’s resultant rate of growth exceeds any other comparable period in Tata’s 152-year history.

In India, three-axle rigids were as big as trucks were, until the highway infrastructure improvement programme got under way.

Truck demand has, in part, been fuelled by the Golden Quadrilateral project; a 3,600-mile orbital highway network linking India’s biggest metropolitan conurbations, including New Delhi in the north, the Kolkata to Chennai corridor on the east coast, Bangalore in the south, Mumbai on the West coast and Jaipur in the north-west. The Golden Quadrilateral has been one of the key priorities in the country’s physical infrastructure development programme. Vast stretches have been upgraded from four lanes to six. Completed in 2012, the project is a giant step – though the fact remains, almost half of India’s roads are still unpaved.

Construction models account for a large slice of Tata sales. The split-windscreen cab preceded the present range.

Economic growth demands more trucks. And more trucks – plus the efficient distribution of goods – require better highways. Tipper- and dump-bodied construction trucks, and in-transit concrete mixers, thus spearhead infrastructure development, from quarrying the enabling raw material and onward to the construction of highways – and the built environment that follows in their wake.

Whether long-established stalwart models, or the latest designs with sophisticated European-influenced features, construction trucks front most commercial vehicle ranges sold in India. Other factors powering the market are tighter enforcement of legislation (for example, until recently, overloading has been the rule rather than the exception), increased availability of vehicle finance and an aging commercial vehicle parc – hence the newly-introduced 20-year age cap. Trucks that are 10 or more years old account for around 40% of India’s total.

New legislation in India bans trucks over 20 years old, reducing the number of trucks like this re-fettled rather than replaced SE 1613.

Numbers and risks

Although as a breed they are on their way to scrappage, comprehensive rebuilds, with ornate embellishments proclaiming immense pride of ownership, have been a common sight. Although the population is 20 times the size of Britain’s, there are only around six times as many motor vehicles. Yet the risk of being killed in a road accident is two-and-a-half times greater.

It’s surprising the carnage isn’t even worse. In the mayhem of motorcycles, scooters, three-wheel rickshaws, cars, trucks and pedestrians, every individual road user appears to harbour an inalienable conviction that they alone have the right of way. The only things drivers, and the frenzied two-stroke hoards, defer to are meandering, hump-necked zebus. In India, cattle are sacred. It’s human life that’s cheap.

Looking pristine after a repaint, is the position of Tata ‘T’ emblem an attempt to deflect attention from the lopsided bodywork?

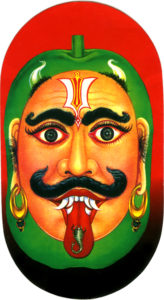

The image of Drishti Bomma, a Hindu talisman that protects against bad energy, is painted on many diff housings.

Many own-account truck drivers recognise that for the preservation of life, limb, truck and livelihood, extra measures are called for. They invoke the help of Dhrishti Bomma, a talisman that protects against bad energy (such as other road vehicles). The image is usually painted on the diff casing, clearly visible to a following driver.

As a consequence of the past lack of the blacktop suited to the operation of heavier commercial vehicles, the archetypal Indian truck – disregarding light commercials – has been a two-axle chassis grossing between 11 and 16 tonnes. Often owner-driven and with a locally-built or DIY, timber-framed cab structure, it’s an icon of Indian entrepreneurial culture. The classic of the Tata range, in production for decades, is the ubiquitous, short-bonnet SE 1613 4×2 16-tonner, that’s available in full-cab and chassis/cowl guises. With cab styling that retains an echo of Tata’s original Mercedes-Benz-based, medium-tonnage commercial, in the land of the bullock cart, the bonneted SE 1613 had long been regarded as the workhorse of choice at the medium-weight, cheap-and-cheerful end of the Indian road transport vehicles market.

Plenty of choice

The overall Tata 16-tonner range comprises both SE 1613 bonneted and LPT tilt-cab and chassis/cowl forward-control counterparts. Collectively, including the uprated LPT 1615 variant, the specs cover four wheelbases and a variety of ready-to-go, fully-built bodywork and equipment options. These extend from reefer, tipper, skip-truck, hook loader and truck-mounted crane to road sweeper, water tanker and garbage compactor.

Tata signed an engine manufacturing joint-venture with Cummins in 1993. While the forward-control LPT 1615 has a 5.9-litre, 159hp Cummins ISBe, 119/125hp Cummins units in the lighter models have been replaced by a 136hp Tata diesel. Gearboxes are a Tata six-speed manual. Military-spec, three-ton-rated 4×4 variants have been exported to armed forces in countries in Africa and elsewhere.

In the land of the bullock cart, when it comes to trucks, the SE and LPT 1613 variants have long been the workhorses of choice. Given that the popularity of the short-bonnet SE, it’s perhaps surprising that bonneted trucks have not been adopted by Tata – and its indigenous competitors – for more recent designs. Instead, virtually all new, indigenously-produced truck designs have been Euro-style cabovers. Given the state of the roads – and the searing heat of the climate – logic suggests bonneted trucks would be preferable.

In production for three decades, at the time of its introduction the 407 series was the first Tata truck design to be less reliant on Mercedes-Benz DNA.

On the seesaw theory, because the driving position is behind rather than above the front axle line, the ride is potentially more comfortable (especially when niceties like a Bostrom seat are sacrificed to strip-out cost). Likewise, the cab interior is likely to be less hot – heat rises, and the driver of a bonneted truck is not seated directly above the engine (and if air con is fitted, it may not have to be as powerful). Finally, in crash-on-regardless driving conditions, a bonneted layout offers the potential safety benefit of the cab being further from a front-impact accident (a fact that Tata recognises in the sales blurb for the SE 1613 military version).

While vehicle length is obviously a mitigating factor, on comfort and safety grounds – setting aside the scope for better aerodynamics and, therefore, fuel savings – instead of taking a lead from Europe, Indian legislators and manufacturers might have been better off following America in ditching cabovers in favour of ‘conventionals’. Put it another way; is there a gap in the market for a product designed from first principles, as a ‘tropical world truck’?

Light-commercial dominance

The early-1970s vintage SE 1613 was joined in production in 1986 by the Mercedes-based forward-control Tata 407 light truck series. A third of a century on, Tata’s light commercial continues to have a dominant share of the two-tonne+ market. Sold in 15 Asian and African territories, and with military truck spin-offs, it’s been the beneficiary of progressive evolution, evinced by the introduction of a CNG fuel option in 2009, and a common-rail diesel in 2010. The bewilderingly wide range includes full forward-control and short-bonnet versions, with 85hp turbo-intercooled, three-litre Tata diesels. Gross weights are up to 6.25 tonnes.

Like this SFC 709, Tata offers the option of complete vehicles. And isn’t this the cleanest gully and cesspool emptier you’ve ever seen?

Next, come two ranges of light-to-medium weights, with grosses spanning nine- to 16-tonnes, and with 123hp. The LPT series has a cab with flatter styling, the other, the Ultra series – of more recent design – is about as curvaceous as a truck could be, within the limitations of an almost flat windscreen. All of these models are available as chassis cabs or in fully-built specs that roll out of the factory doors ready to go straight to work.

Going up the weight scale, Tata produces a comprehensive range of forward-control, middle-weight and heavy-duty rigids, tippers and tractor units, from 16 tonnes and upwards to 55 tonnes for the biggest, three-axle tractor spec.

Standard Tata Prima tractors are up to 49 tonnes gross, though the 296hp ‘Increased Load’ variant is 55-tonne rated.

There are five product groups, within three generic series – Signa, LPT and Prima. The lightest LPT has a cosmetically more macho variation of the cab fitted to medium truck siblings; the heavier LPTs have a shorter bumper-to-back derivative of the Signa unit, with a full-width grille panel that gives it a different ‘face’.

The 37-tonne GVW 10×4 Signa 3718 is Tata’s heaviest standard tipper. The heavy tipper range also includes Prima models.

Top-of-the-line is described as the ‘Increased Load Range’, with higher capacity axles. There are 13 base truck and tractor specs, variously with a 134hp Tata diesel and 178hp, 230hp and 296hp Cummins ISBe engines. Gross weights are in 19-, 28-, 35-, 40-, 42-, 46-, 48-, 49- and 55-tonne increments. The separate tipper range is headed by a 37-tonne-rated 10×4. Standard tractors are up to 49 tonnes; rigids at up to 37 tonnes. Specifications offer reefer and other body options, and Tata also produces semi-trailers.

The top-of-the-range, first-generation, purpose-designed Tata tractor was the 227hp LPS 4923 6×4, grossing 49 tonnes.

Pushing-on

Tata dramatically upped its game, and widened its international horizons, in 2004 with the acquisition of the commercial vehicle manufacturing assets of Korea’s Daewoo, then in bankruptcy. Daewoo’s Czech Republic subsidiary, Avia, was simultaneously acquired by Tata’s Indian arch rival, Ashok Leyland. Tata quickly worked its magic and, within months, was able to debut the Daewoo Novus line-up. The Novus range – now discontinued – comprised comprises diesel-, LNG- and CNG-fuelled tractor, rigid, dumper and mixer chassis, with two-, three-, four- and five-axle variants. Power at the top tractor end was supplied by a 480hp, 15-litre turbo-intercooled Cummins ISX in-line six. The 10×4 rigid, with 420hp, had a gross vehicle weight rating of 45 tonnes. Overall engine options started at 215hp, and offered up to Euro III compliance. Novus export markets included South Africa and Russia – those sold in the latter were badged ‘Tata’.

Launched shortly after Tata took over Korea’s Daewoo, in 2004, Novus heavies are no longer sold in India.

With Daewoo securely embedded, Tata then brought its muscles to bear on the development of its premium-segment world truck family – the Prima series – which has been progressively expanded since its initial launch in 2008. Engineered and spec’d to European standards, the range embraced Euro III- and Euro IV-compliant trucks and tractors with 180-560hp. Heading the weight spectrum was a mining dumper grossing 75 tonnes. The overall range spanned wide and narrow cabs, with day, rest and sleeper length options in regular roof, low dome and high dome configurations. Air con and GPS were standard, automatic transmissions and air suspension were on the options list. Make no mistake, with its Prima range, Tata was showing itself to be a very determined global player. To ensure state-of-the-art engineering, design and development was a collaborative effort bringing together teams in India, Korea, Italy (where the Prima cab was styled) and Tata’s Warwick-based European Technical Centre in the UK.

The Korean products are now badged ‘Tata Daewoo’. The Novus range is no longer in Tata’s Indian line-up, though some Prima specs remain in the portfolio of models sold into the Indian market.

Tata’s current range of logistics and special-role army trucks spans 4×4, 6×6, 8×8, 10×10 and 12×12 chassis variants.

Tata is a long-entrenched supplier of tactical and logistic trucks to the Indian Army and the military of other nations. More recently, it’s positioned itself alongside the established makers of big military trucks with high mobility, multi-role 8×8, 10×10 and 12×12 platforms, supplementing all-wheel-drive two- and three-axle chassis. The 12×12 has 525hp and a chassis with three axle pairs, with both front and rear pairs steered.

Will Tata trucks come to the UK? If the pricing and quality were right, it might squeeze in somewhere – but with battery-power and hydrogen-fuelled developments on the horizon, long-term, it would probably be a no-no. That said, might the all-electric tech Jaguar has developed for its new XJ flagship – due for launch this year – work in a truck?

Despite the Tata group’s ownership of Jaguar – which took over Guy in 1961 and launched the Big J – Tata would be most unlikely to revive the badge of Wolverhampton’s finest. And not because the war-bonneted Indian chief emblem is the wrong kind of Indian. The Guy trademark is owned by Paccar, parent of Kenworth, Peterbilt and DAF.

For protection against ‘bad energy’, Drishti Bomma is painted on many diff housings. Mind you don’t get brake tested!

To subscribe to Heritage Commercials magazine, simply click here