The amazing history of truck builder, Thornycroft

Posted by Chris Graham on 7th July 2023

Ed Burrows explores the fascinating history of truck manufacturer Thornycroft, that started life building Thames motor launches then warships!

Images: Ed Burrows and archive, Hampshire Culture, Thornycroft Register/Andy Ballisat

In civilian operation, the WW1 3-ton payload-rated Thornycroft J-type could carry six-tons.

Remarkably – though not so remarkable once the business is properly understood – at peak, 95 percent of a Thornycroft truck’s components were manufactured in-house by Thornycroft. Chassis, cabs, engines, gearboxes, axles, the lot. And each item superbly engineered with the emphasis on reliability achieved through an emphasis on simplicity, as anyone with mechanical familiarity with Basingstoke products would attest.

Although associated with the sprawling Hampshire factory complex occupied for the 71 years between 1898 and 1969, the marque’s history predates that. And trucks were also produced afterwards when – long after the 1961 AEC takeover – Thornycroft co-existed with Scammell in Watford under the Leyland Special Vehicles banner.

Between the first ‘commercial’ – the front-drive, rear-wheel steer No.1 Steam Van of 1896 – and the last Thornycroft in the late 1970s, total production exceeded 60,000 vehicles.

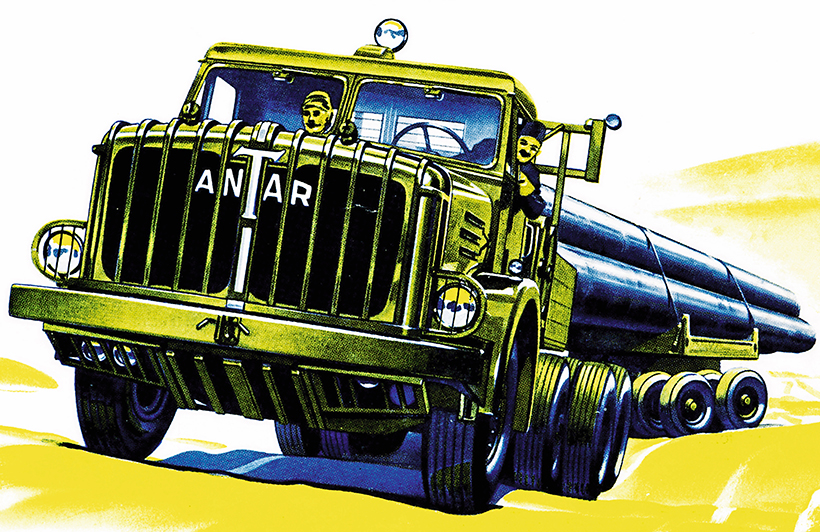

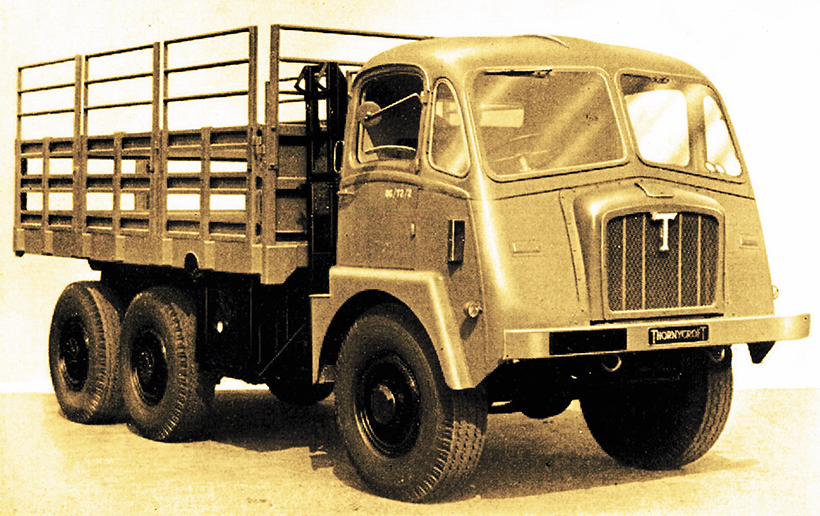

Mighty Antar: engineering tour do force that led European truck design and power outputs in a new direction.

Thornycroft’s origins date to the marine engineering interests of John I Thornycroft. The business was constituted as John I Thornycroft & Co in 1866, following the success of a 36ft launch constructed by the founder. He also built its steam engine. It had the distinction of being the first Thames steam launch capable of keeping up with the eight-oared rowing boats in the annual Oxford versus Cambridge University boat race.

John I Thornycroft started the project in 1859 at the age of 16. Completed three years later, it was built in the Thames-side Chiswick, Middlesex studio at the home of his sculptor parents.

Although moving in elevated social circles, Thomas and Mary Thornycroft were most definitely not idle gentry. The best-known sculptural work of Thomas, John’s father, is Boadicea and Her Daughters, the monumental bronze of the rebel queen in her chariot located by Westminster Bridge and facing Big Ben.

Thomas had a strong interest in mechanical engineering and encouraged his son. This led to John studying engineering at Glasgow University after spending time with a shipbuilder and iron founder on Tyneside, after which he qualified as a Naval Architect.

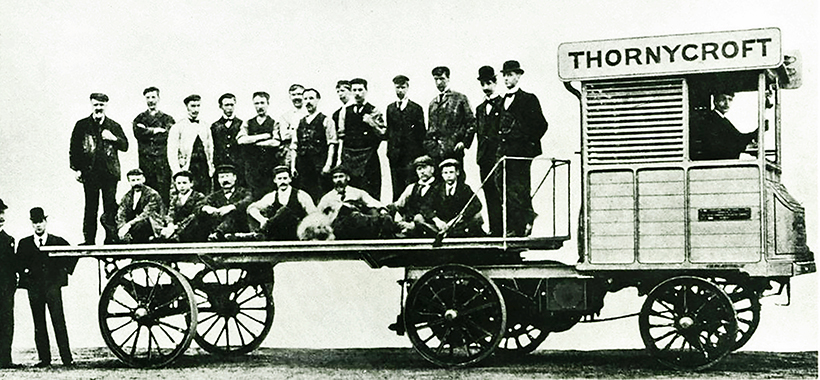

Did Thornycroft invent artics? No other make appears to have evidence that predates this 1898 steamer.

Like his parents, John had an artist’s eye for line, which was expressed in the design of the hull forms of a series of craft that secured the company’s reputation. And proof of his inventive turn of mind, between 1873 and 1924 he registered over 50 patents.

A boatyard was established in Chiswick. The tenth steam launch, built in 1871, attained a speed of more than 16 knots (18.4mph) – a new performance benchmark at a time when ocean steamships did not exceed 14-knots. Five years later Thornycroft added seagoing vessels to Thames launches.

The Royal Navy had begun arming ships with torpedoes. The Admiralty also sought a fast attack craft that could get within 600 yards of an enemy warship, launch a torpedo then rapidly exit the scene.

In 1877, Thornycroft delivered the Royal Navy’s – and the world’s – first motor torpedo boat, HMS Lightning, 80.5ft long and displacing 30-tons. Exceptional for the time, it had a service speed of 18 knots (20.7mph). Driven by the quest for speed, John I Thornycroft and his team experimented with hull forms and, later, on refining the shape of propellers to improve efficiency.

To ensure even weight distribution when loaded, chassis layouts available included set-back, set-forward and engine-above-axle arrangements.

By the time the No.1 Steam Van was completed in 1896, in the 30 years since its inception, Thornycroft’s Chiswick boatyard had delivered some 300 vessels. The largest built at Chiswick was HMS Speedy, an 810-ton torpedo gunboat, significant for being the first Royal Navy ship with water tube boilers, which reduced weight and increased speed.

The No1 Steam Van, a project led by John E Thornycroft – John I’s eldest son – took the business in a new direction, signified by setting up The Steam Carriage and Wagon Company.

The design of its water tube boiler type steam engine benefitted from Thornycroft’s marine steam engine knowhow. The back-to-front (rear-steer, front-drive) layout of No.1 was soon superseded by designs of conventional layout.

With Chiswick boatyard at full capacity, a new factory dedicated to vehicle manufacture was opened in Basingstoke in 1898. In the same year, though not proceeded with as a production model – but revived in the 1930s – Thornycroft built what could lay claim to being the world’s first artic.

Bonneted specification options like this tipper included a set-back steering axle with cantilevered engine.

In 1904, Thornycroft took over a shipyard at Woolston, Southampton. Six years later the Chiswick yard was relinquished.

Two years prior to Basingstoke opening, an Act of Parliament withdrew the requirement that horseless carriages required a pedestrian carrying a red flag to walk 60 yards in front. This was later reduced to 20 yards. Also, the speed limit for road-going locomotives was raised to 14mph from 2mph in populated areas and 4mph elsewhere.

Thornycroft’s immediate response was the No.1 Steam Van prototype.

The early years of the twentieth century witnessed John I Thornycroft applying his intellectual powers to challenging erroneous theories about the principles of hydrodynamics. He also led the progressive development of water-tube boilers, which were substantially more efficient than the conventional locomotive type.

In WW2, some 5,000 4×4 Nubian three-tonners served with the British Army and the RAF. With an 85hp petrol engine, it could climb – and stop and restart – on a 1-in-2 gradient.

In that era, the Royal Navy was the world’s largest. Thornycroft being the pioneer of motor torpedo boats and fast naval craft, the relationship with the Admiralty was close. Attempts to keep up with the best won exports to other navies, ranging from Spain, Russia and Japan to countries in Scandinavia and Continental Europe.

In tandem with developing automotive and marine petrol engines, between 1903 and 2013 motorcars were produced, with 10bhp/two-cylinder and 20bhp/four-cylinder petrol engines. A year later the cars were joined by 2-/2.5-ton capacity lorries, with the first oil-engined 2-/2.5-ton goods vehicles appearing in the same year.

Interest in steam wagons and tractors was heightened in the early 1900s by winning a War Office trial, followed by steamers being purchased for the British Army. These served in the Boer War in South Africa.

Capitalising on the performance of the steamers in South Africa, ‘Colonial’ models was produced with larger boilers and stronger frames. These won export sales to West Africa, the Congo, India, Burma, Singapore, New Zealand and the European mainland.

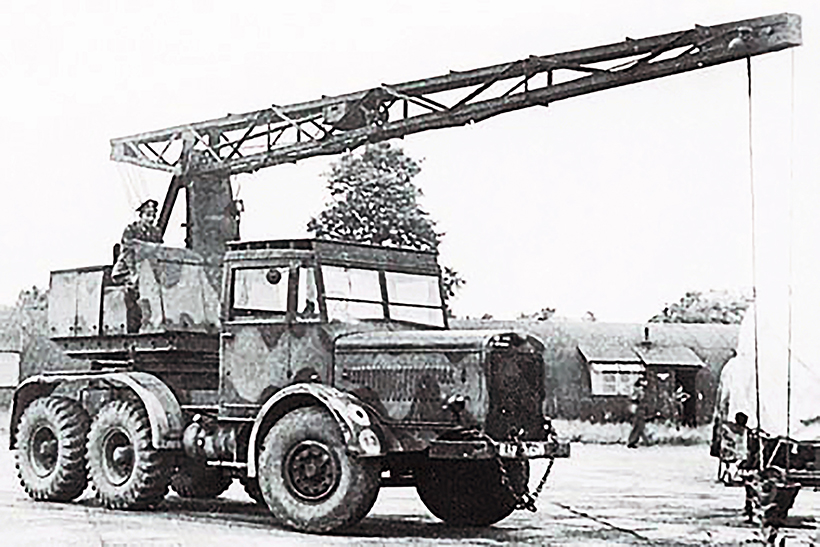

Mostly serving with the RAF, during WW2 Thornycroft delivered 2,000 Amazon 6×4 chassis for Coles six-ton airfield crash rescue cranes.

Next down the production line were buses and coaches, a Thornycroft market until WW2.

Neither PSVs nor ships are in Heritage Commercial’s orbit, but with the latter a main driver of the Thornycroft business, it merits coverage – especially a vessel as such as WW1’s HMS Teazer, which during trials in 1917 exceeded 40-knots (46mph). With 29,000 horsepower propelling its 1,100 tons, its performance was without precedent for a naval vessel.

In 1911 – three years before the start of WWI – the War Office made what then the momentous decision to move from dependence on equines and introduce motorised transport vehicles. (Nonetheless, during the Great War the armies of Britain and the Commonwealth employed over a million horses and mules, used to pull supply wagons, artillery and for many other duties).

After 1911, the War Office introduced the Subvention Scheme. Under this, for specific types of lorry – selected after a series of tough military trials – civilian operators were paid a subsidy conditional on the vehicle being requisitioned in the event of war.

A 1948 62hp, 3,865cc, four-cylinder side-valve petrol-engined Sturdy five-/six-ton tipper, restored to retain the patina of age. It’s hard to believe that the design of the radically advanced Mighty Antar commenced the following year.

Thornycroft was a prominent supplier of subvention vehicles and direct War Office purchases. In all, around 5,000 Thornycroft J-types saw military service. Although their rated civilian payload capacity was higher, they were classed by the War Office as three-tonners.

The shaft-drive, 4×2 J-type was powered by a four-cylinder Thornycroft petrol engine driving through a four-forward speed/1-reverse gearbox. Output was 44.5bhp at 1,800rpm. With a 4.5in bore and a 6in stroke, capacity was 6.256-litres.

The inlet and exhaust valves were on opposite sides of the head. While the arrangement was falling out of favour at the time with other makes, it gave excellent low speed pulling power and made access easier for routine maintenance.

This 1956 Trusty represents the first generation of Thornycroft eight-leggers. Max gross rigids do not appear to have been in the line-up prior to WW2, and didn’t survive the 1960’s AEC/Leyland realignments.

Basingstoke’s three-tonner was readily identified by its distinctive wheel design, which contrasted with the spoked wheels of almost all other Allied military types. To lighten the conical casting, the wheels had eight large circular cut-outs. Rear wheels were larger diameter, sometimes fitted as twins. With an unladen weight of 4.45-tons, main dimensions were: 22.24ft long, 13.96ft wheelbase and 7.25ft wide.

Alongside the main general service cargo truck, bodywork variants included mobile workshops and anti-aircraft artillery platforms, equipped with ground jacks to counter gun recoil.

In the years after WW1, unlike manufacturers who found it tough to compete with war surplus disposals, The Basingstoke business was reasonably secure, thanks to the reputation earned by the J-type for durability and reliability. Reconditioned examples were popular, and the firm benefitted from the introduction of the X type three-tonner, essentially a cheaper, de-militarised J type. Pre-war foresight in building exports also contributed, with sales through branches or agencies in Commonwealth and other countries. Load capacities were between two- and six-tons, and specs included both normal and forward control options.

Big Ben 6x4s were produced in forward control and normal control versions, the latter sporting adapted Antar Mk3/3A cabs and bonnet panels.

The UK goods vehicle market was not exactly booming, and in 1924 received a boost in the form of the introduction of a revived Government subsidy scheme. A qualifying vehicle was the 1.5-ton payload Thornycroft A1, introduced the same year. A 25% subsidy on the purchase cost new was paid by the Government over three years if the vehicle was properly maintained and available in the event of a national emergency. Powered by a 36bhp ‘four’, the A1 was nippy and, rather than sole reliance on the subsidy scheme won sales on its own merit. Two-ton capacity versions were added in 1926.

During this period, the engineering team gained a substantial leg-up in knowhow by courtesy of a contract to build five-ton gross Hathi 4×4 open-top artillery tractors. Reflecting the fact that British manufacturers were behind others in developing all-wheel-drive, an Army workshop had assembled a prototype of a vehicle on these lines from captured German components. Covering a run of 25 vehicles, the contract placed with Thornycroft filled the gap in the company’s previous all-wheel-drive transmission experience. The Hathi also raised Basingstoke’s game on the engine front, following its development of its 90-/100-bhp, 11.3-litre petrol ‘six’.

A 1955 Sturdy Star, representative of four-, six- and eight-wheelers of the period. Versions of the cab also featured on the three-axle Nubian and Mk3/3A Antar.

A Hathi could tow five tons up a 1-in-4 gradient, restart on a 1-in-5 and maintain 22mph for over two hours. The driveline was mechanically complicated, but some of the 25 were still in service at the end of WW2.

Over the course of the 1920s and 1930s, although concentration was on two- to eight-tonners, listed specifications included eleven-ton six-wheelers and, although sales were poor, articulated types. And no manufacturer had a wider range of chassis options. In the interests of optimal weight distribution, there were cabovers variously with the engine directly above the axle, set-back axle and set-forward axle. Normal control specs offered a choice of engine over the axle or cantilevered out front of the steering axle. The range also included single- and double-drive six-wheelers. Engines were petrol fours and sixes, with diesels coming to the fore as the 1930s progressed.

A 26-tonne gross Mastiff six-wheeler with glass-reinforced plastics cab exported to Australia in late 1960. The original 130hp T hornycroft diesel was later replaced by a 180hp Gardner 6LXB.

In the build-up to WW2, British Army 6×4 ‘General Service’ cabovers gave way to contracts for 5,000 Nubian three-ton 4x4s, a type that became the basis for post-war off-highway developments. Powered by an 85bhp, four-cylinder petrol engine, the Nubian could climb a 1-in-2 gradient and hit 40mph, so could probably claim superior performance to Bedford and other British Army three-tonners.

Basingstoke’s wartime output also included 8,230 Bren Gun-type Carriers and over 2,000 Amazon 6×4 chassis for Coles six-ton airfield crash rescue cranes.

In 1948, the Basingstoke business was reconstituted as Transport Equipment (Thornycroft) Limited, clearly separating it from the shipbuilding side.

1960s Nubian 6x6s were supplied to oilfield operators. The type was trialled by the British Army, but no contract was awarded.

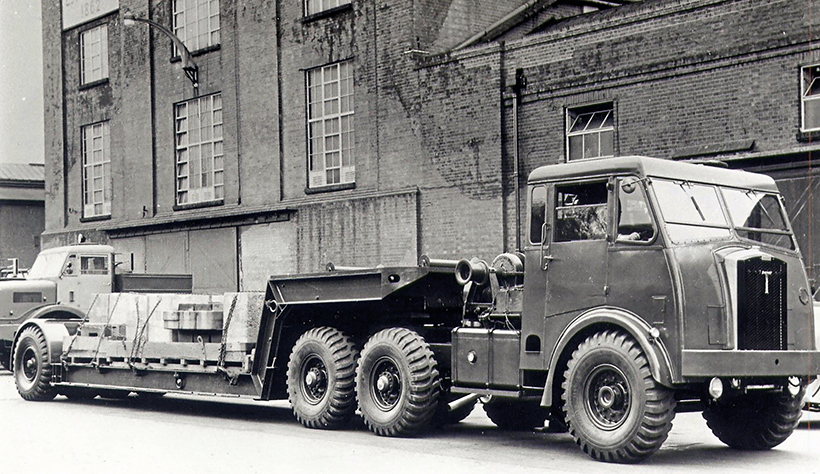

Having previously specialised in robustly engineered light/medium weight trucks, in 1949, with the Mighty Antar, Thornycroft reinvented itself as the UK truck manufacturing industry’s heavyweight champ.

Flexing their muscles below the Antar were forward and normal control Big Ben and Nubian rigid trucks and tractors, and a full range of regular goods specs – including Thornycroft’s first eight-wheelers, a configuration it does not seem to have been produced prior to WW2.

The 6×4 Antar was designed at the instigation of civil engineering contactor Geo Wimpey, which had been awarded a contract for the construction of a pipeline in Iraq. The Basingstoke team took only ten months from the initial order being placed to commencing service in 1951 transporting pipeline sections over a 350-kilometre route across stony desert.

Serving with the RAF and many overseas airport fire and rescue authorities, successive generations of Nubian Major 6×6 C-F-R foam appliances progressed from front- to rear-engined layout as tonnages increased.

Each Antar hauled over 60 tons of 93ft long pipes. Between them, five trucks carried the sections required to construct a kilometre of pipeline. With an unladen weight of 15.5-tons, the Antar had a bogie capacity of 36 tons and a rated maximum gross combination weight of 100 tons. Power was supplied by an 18-litre Rover Meteorite V8 diesel driving through a four-speed dog box and three-speed auxiliary. Catalogued outputs were 250bhp at 2,000 and 728-lb/ft at 1,250rpm. The Meteorite was developed from the Rolls-Royce Merlin V12, the WW2 engine that powered RAF Spitfire, Hurricane, Mosquito, Lancaster and other warplanes.

Trials in the UK, quickly followed by exemplary performance in harsh desert conditions, led the UK Ministry of Supply to recognise it had an almost off-the-shelf solution to the Army’s need for a tank transporter for its new – and technically world leading – Centurion tank. The first UK military orders were placed in 1951.

The Antar Mk3/3A followed a decade later. An extensive rework, it was spec’d to move the Centurion’s heavier successor, the Chieftain Main Battle Tank. Power was supplied by Rolls-Royce’s magnificent 333bhp C8SFL supercharged straight-8 diesel.

All told, Thornycroft delivered an impressive total of over 750 Antar tank transporters, oilfield flatbeds and tractors of various types.

Thornycroft continued to offer oilfield specials derived from the Mk3/3A Antar at both the higher performance and medium weight ends of the spectrum. The former included desert tractors running on 21.00x25in low pressure balloon tyres. The latter comprised Big Ben three-axle rigids and tractors grossing circa 25-/30-tons using adapted Mk3/3A front ends and powered by 165bhp Thornycroft turbo-supercharged diesels. Below these were five-ton rated Nubian 4×4 and Nubian Major 6×6 forward-control chassis from which evolved a highly successful airfield fire-crash-rescue (C-F-R) range.

In 1961, Thornycroft was taken over by AEC’s parent the ACV Group. This was followed by the latter’s reversal into Leyland Motors, which precipitated the stripping out of the goods vehicle range and concentration on C-F-R chassis and other on-/off-highway custom-builds. Then, as the British Leyland conglomerate approached its denouement, the core engineering team were reversed into Scammell in Watford, which was then operating as Leyland’s Special Vehicles Division. C-F-R chassis continued to evolve, with the power and weight progressively upped to match the increasing size of airliners.

This continued after the Unipower takeover of the Scammell business, whose final C-F-R specs included 710-bhp 8V92TA V8 Detroit Diesel power.

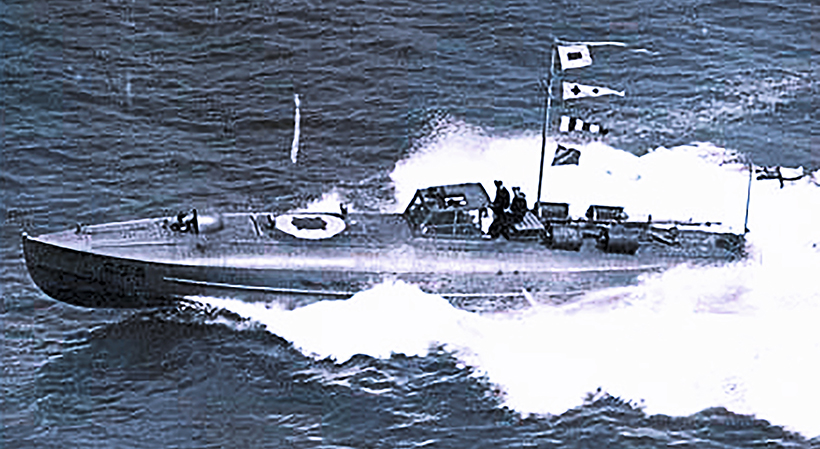

Nautical heritage: way ahead of contemporary truck power and performance, WW1 Thornycroft coastal patrol boats like this had 500hp and were capable of 33 knots (38mph).

And the shipbuilding side? In the 1960s, it merged with the equally legendry warship builder Vosper to create Vosper Thornycroft. It’s now part of the BAE Systems, Britain’s leading defence contractor.

For most of its history, Thornycroft’s bread and butter comprised relatively unspectacular, well-engineered medium weights.

What astonishes is that Basingstoke’s most original design – the Mighty Antar – did not appear for a century after John I Thornycroft’s first flourishes of creativity. Nothing like it in size, tonnage and capability had ever been seen before. Credit where it’s due: the Antar was Europe’s first modern, all-new super-heavy truck design.

This feature comes from a recent issue of Heritage Commercials, and you can get a money-saving subscription to this magazine simply by clicking HERE