Austin A30/35 commercials

Posted by Chris Graham on 11th September 2020

Peter Simpson tells the story of the popular Austin A30/35 commercials, and provides some up-to-the-minute buying advice.

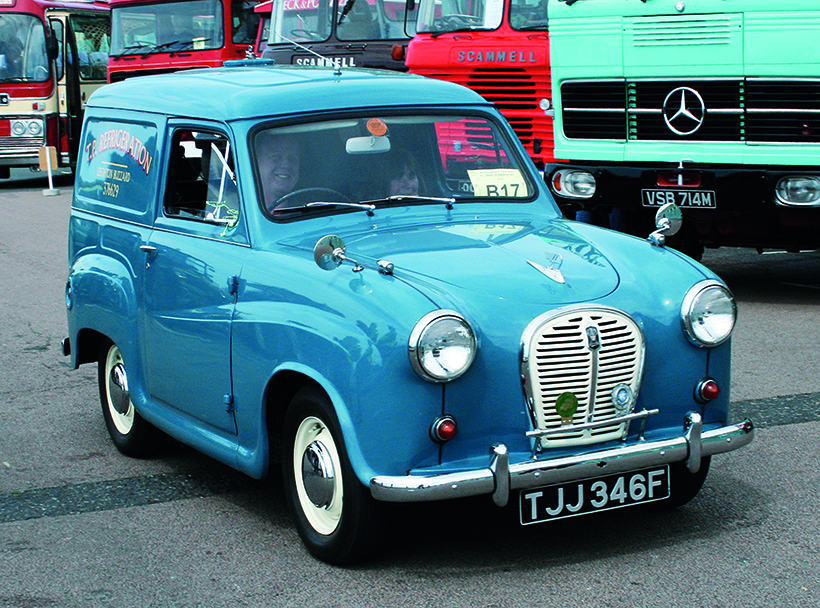

Austin A30/35 commercials: Richard Dracup’s fine and fully restored 1968 A35 crossing the finish-line on the 2016 HCVS Brighton Run. Production ended in ‘68 and, by that point, only the 848cc engine was offered by the factory, though this particular van has a 1,098cc unit. (Pic: Peter Simpson)

I will admit to having a strong affection for Austin A30/35 commercials – I had and A35 van as my very first car, back in 1977. 484KOG was a 1963 example – so 1,098cc – in Spruce Green. I owned it for just one year and it was scrapped not long after I sold it. Sadly, I have no photographs of it as I had no interest in photography then, or any inkling that I’d spend pretty-much my entire working life in a profession where such things might be useful. But as most people do, I recall my first car with great affection.

The A35 was chosen for several reasons. Obviously low running costs were a consideration, and a van was useful as I was already doing a bit of dealing. The primary consideration, however, was that it was cheap – bought via a shop-window postcard advertisement for £50 in running order, and with a long MoT. But it had sills that were unlikely to pass another, as the test had been upgraded in 1977, and the rules on structural corrosion and acceptable repairs were tightened significantly.

An A30 van – note chromed radiator grille. Originally fitted with an 803cc A Series engine, this one has, like many others, had an engine swap. (Pic: Russ Harvey)

Needless to say, the days when any A35 van could be bought for £500, let alone £50, have now gone for good. As has always been the case, however, A35 vans are still slightly cheaper than Minors in equivalent condition, and also rarer. Load space is, however, smaller, and though mechanical parts availability is generally OK, body restoration requires a lot more repair than renewal.

Basic design

Compared to a Minor, some aspects of the A30 and A35 are also a little, shall we say, ‘basic’. For example, there’s no key start, and thus no starter relay. The key-controlled ignition switch is a simple, two-position off/on affair. Once it’s on, you pull a starter knob on the dashboard, which links directly via a short rod to the high-power starter solenoid on the other side of the bulkhead. This makes the connection and starts the engine.

Short-lived factory pick-up was an attractive vehicle, but the loads pace was too small and inaccessible for it to be regarded as a commercial vehicle for tax purposes. (Pic: Russ Harvey)

Then there’s the braking system. This is hydraulic only at the front; the rear brakes are rod-operated, with a single, frame cylinder half-way down which converts hydraulic power into mechanical. This was old-fashioned even when the A30 was new, but the system is up to the modest performance of an unmodified A35, but does need regular maintenance. Of course, any engine power upgrade must be accompanied by upgraded brakes.

At one time, people simply bolted on an all-hydraulic A40 Mk2 system but, nowadays, such parts are scarce, to put it mildly. Austin-Healey Sprite/MG Midget systems offer another alternative but, while wearing stuff is generally available, parts that don’t wear out can still be tricky.

Home-made A35 pick-ups – made by cutting a van down – weren’t uncommon. Though converted in the 1960s, this one remains in limited farmyard/commercial use today. (Pic: Brian Culpan)

The A30/A35 vans lasted longer in production than the cars on which they were based; the A35 saloon was effectively replaced by the Mini and A40 in 1959, but the A35 van was made right up to February 1968. There were two main reasons for this. Firstly, although Mini-based light commercials were available from 1961, many traditional van buyers had concerns about the reliability and repair costs associated with front-wheel-drive; concerns which were reinforced by a number of well-publicised driveshaft coupling and other failures.

Secondly, when Austin and Morris merged to form BMC in 1952, both companies bought with them a large dealer network, meaning most towns had an Austin and a Morris dealership. Locally, these were competitors, and that hadn’t changed because Austin and Morris had joined forces. Hence BMC’s extensive use of badge engineering with slightly different Austin and Morris versions of the same vehicle.

Genuine examples of the Countryman are now rare – this restoration project was spotted on the club stand at the 2012 NEC Classic Car Show. The best way of distinguishing a factory-built Countryman from a van conversion, is that the former doesn’t have a small opening air-vent in the roof. (Pic: Peter Simpson)

Morris dealers could offer Morris Mini and Morris Minor vans, so Austin dealers also had to have a small RWD van. This competing, in-house dealership situation lasted into the 1970s in some cases meaning that, when the A35 van was finally discontinued, BMC had to produce an Austin-badged version of the Minor Van to fill the gap until the Marina-based vans arrived in 1972 – and these, too, were initially offered with ‘Austin’ or ‘Morris’ badging.

Anyway, the A30 saloon was launched in October 1951, with the 5cwt van following just under three years later, in August 1954. Van upgrades included stronger rear springs – 11-leaf instead of eight – and 5.90×13 tyres rather than 5.20. The engine was the BMC A Series in 803cc form, the A30 being the first vehicle to use this engine which was to serve BMC and its successors for well over 30 years, though the 803cc version had many detail differences compared to later incarnations.

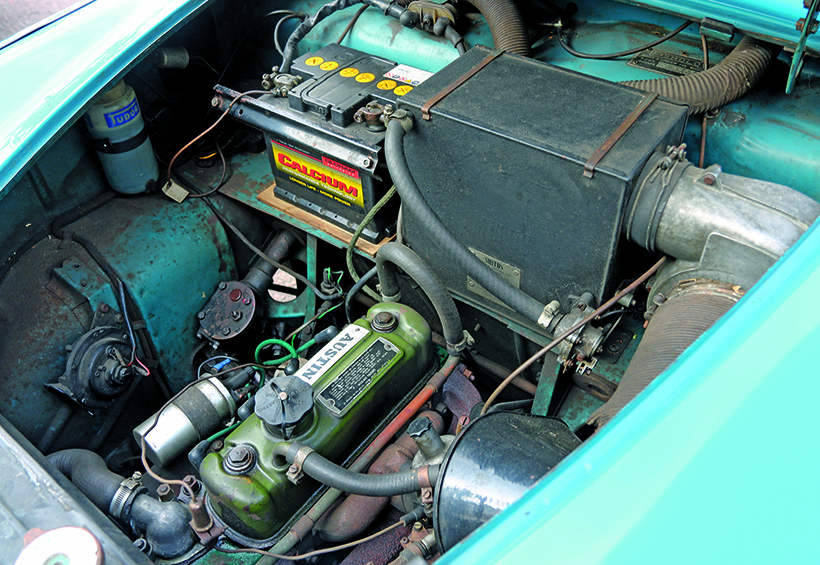

Engine sits well down in the bay, and there’s loads of space all round. (Pic: Nick Larkin)

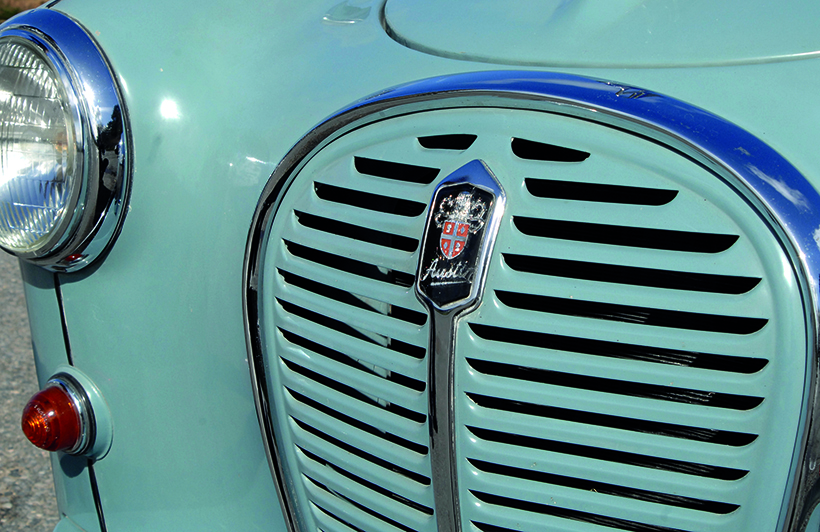

In September 1956, the A30 range – cars and van – was upgraded to the A35, with the main difference on the van being an engine capacity increase to 948cc (low-compression, and quite happy on two-star petrol), plus a remote gearchange instead of the long, direct-acting and much less precise A30 arrangement. Externally, the radiator grille was painted (body-colour) rather than chrome. However, while flashing direction indicators replaced the A30’s trafficators on the A35 saloons, the A35 vans – somewhat surprisingly – retained trafficators right up to February 1962. Who else recalls tapping the door pillar to persuade a sticking one to operate?

Commercials continued

As already noted, the A35 saloons were replaced in 1959. In theory, the successor was the A40 but, in practice, many buyers chose a Mini instead. The A35 van, however, remained in production alongside the Countryman, which had been introduced, in A30 form, in September 1954, developed into an A35 Countryman alongside the saloon. This was, in effect, a van with factory-fitted rear windows, rear trim including a full-length headlining and a fold-down rear seat of better quality than the one that could be specified with a van.

Central-mounted instrument clusters were common on cheaper vehicles, as they made production of LHD and RHD versions easier. (Pic: Nick Larkin)

The van was upgraded twice in 1962; first in February when, as well as finally acquiring flashing direction indicators, the wheels and grille were finished in Old English White – the wheels had hitherto been black and the grille had matched the body colour. Additionally, the front doors which had hitherto incorporated pressed-in sections, became plain, and a thin, bright metal waist strip was added.

Then, in September 1962, the 948cc engine was replaced by a 1,098cc version. A stronger gearbox was also fitted, along with a higher-ratio rear axle, and the Zenith carburettor was replaced by an SU unit. While this change was prompted by the A40 and Morris Minor also moving to 1,098cc and the 948 A Series being discontinued as a result, the A35 van engine had different pistons and was, therefore, a lower compression unit and still happy on two-star petrol. Even so, the 1,098cc van was the fastest A35 of all in standard form, with a top speed of 80mph, and a 0-60 time of 23 seconds.

The rear door retained indentations throughout the van’s production – presumably for added strength – but they were deleted from the front doors in 1962. (Pic: Nick Larkin)

With this change, the A35 van’s official payload was raised to 6cwt, and a few other minor upgrades also carried out – for example the kingpin and stub axles were strengthened slightly. An interior light and windscreen washers were also fitted as standard from this point; the latter because they were about to become compulsory under Construction & Use regulations. At the same time the Countryman version was dropped.

Two years later, in September 1964, something slightly surprising happened – the A35 van was offered with a 34bhp 848cc engine as an alternative to the 45bhp 1,098cc unit. This was initially done at the request of Great Universal Stores, which wanted to buy a fleet of A35 vans for local delivery work, but felt the 1,098cc engine was too powerful. Although the 848cc A Series was very familiar in the Mini, the A35 van was the only time it was ever offered in RWD form and, though it’s unknown what size of order GUS had suggested, reworking the 848 into a RWD engine does seem a massive amount of work for just one fleet buy. It would surely have been easier to simply restrict throttle movement in some way; unless, of course, BMC had something else in mind for an inline 848cc A-Series.

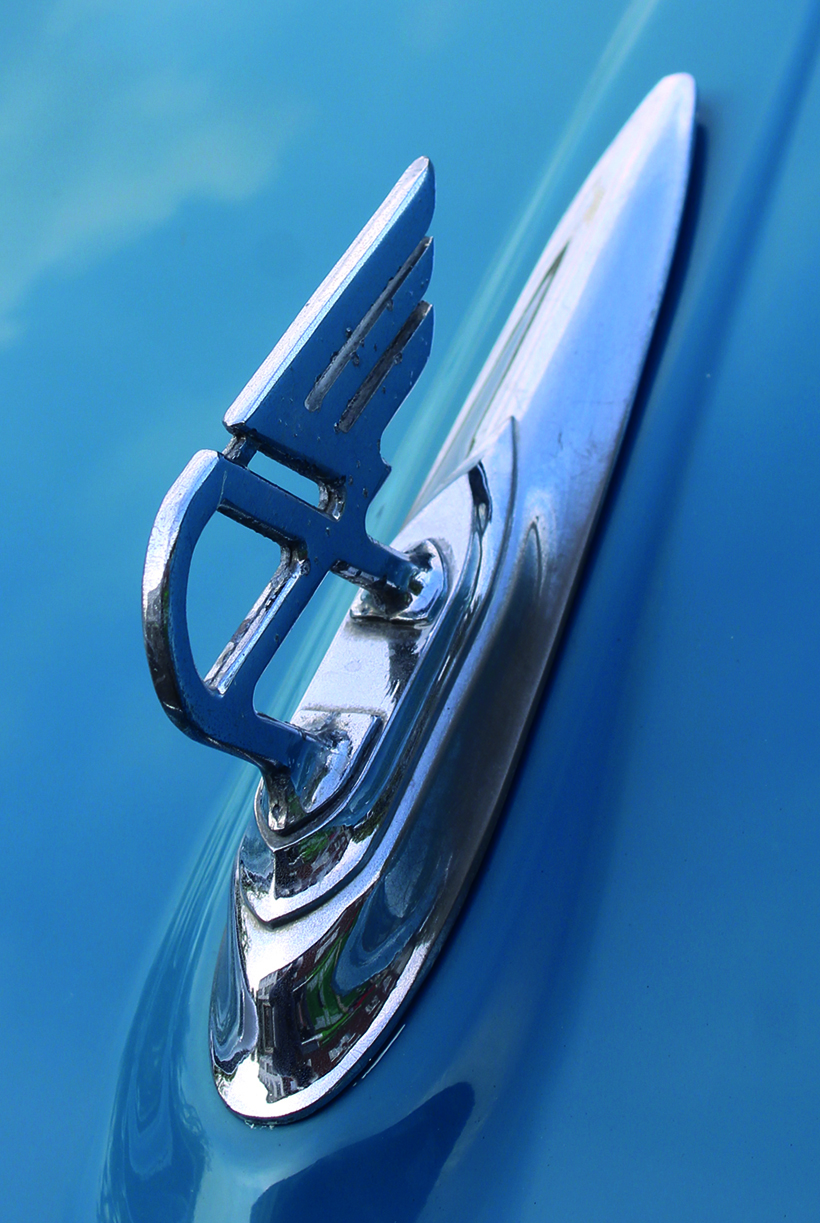

The ‘Flying A’ on the bonnet actually conceals the bonnet release. (Pic: Nick Larkin)

In the event, GUS bought just 200 848cc A35s but, having put the smaller engine into production, it made sense for it to be offered as an option to anyone and, accordingly, customers had a choice of 848 or 1,098 power from September 1964 until May 1966, when the 1,098 version was dropped. This left the 848 as the only option until production ended in February, 1968.

While the 26,047 A30 vans – out of a total A30 production of 222,823 – represented only around 15% of total production, the A35 vans actually sold better overall than the cars and, of the 353,850 A35s made, 210,575 (or nearly 60%) were vans. Clearly, the much longer production run (nearly 12 years compared to three for the saloons and six for the Countryman) was a consideration here, though numbers dropped significantly each year from 1963 onwards, going from 22,247 in 1962/3 to just 3,773 in 1967/8. That’s not really surprising; compare the A35 with its part-mechanical brakes with the Mk1 Ford Escort van, which was introduced just two months after the A35’s demise, and it’s easy to see just how much things had moved on.

The rare one

There was, of course, another A35 commercial variant; the factory-made pick-up. This was made between September 1956 and November 1957 only and is, as is well-known, now an extremely rare and sought-after A35 variant. It’s completely different from the car and van from the doors back. The cab was fully enclosed, and the 15cu.ft loadspace was surrounded by curved, rear bodywork with the spare wheel mounted on the back. There was no opening tailgate, and the small loadspace included a pair of open, occasional seats. It was these seats, however, along with the small and relatively inaccessible loadspace, which sealed the A35 pick-up’s fate; HM Customs & Excise said it wasn’t a commercial vehicle and was, therefore, subject to Purchase Tax which, unlike VAT, was a tax which couldn’t be reclaimed. The exact number made is uncertain, but the total is thought to be around 475, with many dealers ending up registering and using them themselves.

Somewhat surprisingly, the A35 van retained trafficators right up to 1962, though the car had flashers from 1956. (Pic: Russ Harvey)

Buying one

As usual with light commercials, most that have survived long enough to be preserved have done so through being exceptions to the usual life-cycle. A survivor may, for example, still be around because it was used privately, or on unusually light work, or because, rather than being scrapped when no longer viable, it was ‘set aside’ in a barn where it remained for long enough to become rare and sought-after.

Most will have had some repair or restoration, even if they’ve been off the road for some time and, generally speaking, the longer a vehicle like this has been out of circulation, the more likely it is that any repairs will need redoing. In part this is because of natural aging, but it’s also true that it’s not that long ago that values didn’t really justify major work. Panel availability is, of course, patchy and, in most cases with things like wings, it’s a case of using repair sections to mend what you already have, rather than fitting replacement panels.

The painted grille on A35s was body-coloured until 1962; after that it was Old English White on all models. (Pic: Nick Larkin)

Generally speaking, A30/A35s go in the usual places for unitary construction vehicles – inner and outer sills, floorpans, spring mounts and so on. The bottom of the rear wing/wheelarch section is also a common and very noticeable rot-spot. Fortunately, A35s don’t generally hide problems that much, so the rot you see from a normal eyes-open inspection tends to be the rot there is. As usual with unitary construction vehicles, though, the sill closing sections are under the front and rear wings, and a bit of visible rot here always means more severe problems underneath. Also, as usual with commercials, look out for rot in the roof guttering; this can be repaired, but it’s not easy to do yourself, or cheap if tackled professionally.

The mechanical side is straightforward, with parts generally easy enough to find; the fact that much of the A35’s mechanical set-up was also used on the Austin-Healey Sprite and MG Midget is a great help here. Some A35-specific stuff, such as brake master cylinders and the frame cylinder that operates the mechanical rear brakes, are scarce, and it’s often a case of repairing or refurbishing what you already have or, as already noted, upgrading the entire system. Improved brakes are essential if any mechanical upgrade beyond the 45bhp 1,098 A Series is envisaged, and it’s relatively easy to make these vans go better by fitting more powerful engines, or tuning what’s already there.

A35 van on the move. It’s not widely known, but the 1,098cc van – available from September 1962 to May 1966 – was actually the fastest of all the A35 family. (Pic: Nick Larkin)

Price-wise, running and showable vans currently seem to start at £7,000-8,000; anything less than this is likely to need some work at least. Top dealer price for excellent though not concours examples are around £15-16K. As has happened to so many other car-based LCVs, van values have overtaken cars.

Restoration projects are scarce and tend to be snapped up quite quickly and by word of mouth rather than through being advertised. This makes giving accurate values tricky but, as a very rough guide, we’d suggest £1,500-£2,000 as a starting point for something that’s complete and viable for full restoration.

For a money-saving subscription to Classic & Vintage Commercials magazine, simply click here