Life and times of the pocket battleship Admiral Graf von Spee

Posted by Chris Graham on 19th December 2023

James Hendrie recounts the short career of the German pocket battleship, Admiral Graf von Spee, which sank nine ships before being stopped.

All photographs copyright Michael W Pocock/martitimequest.com

Admiral Graf von Spee was designed in such a way as to circumvent the limitations of warship design placed on nations by the Treaty of Versailles.

Over 90 years have passed since the keel of the battleship Admiral Graf von Spee was laid down, on 1st October, 1932, at Wilhelmshaven. Graf Spee was a Deutschland class Panzerschiff which entered service with the German Kriegsmarine on 6th January, 1936. Her design was constrained by limitations imposed by the Treaty of Versailles, but Graf Spee and others of her class became known as ‘pocket battleships’, primarily because of their powerful 11-inch guns.

The Deutschland class were not allowed to exceed 10,000 long tons, according to the Treaty. To overcome this, the designers used lightweight construction methods, including electric welding rather than traditional riveting, as well as economical diesel engines. The ships, including Graf Spee, were neither battleships nor cruisers, but something in between. But they had formidable armament and speed, making them a real attacking threat.

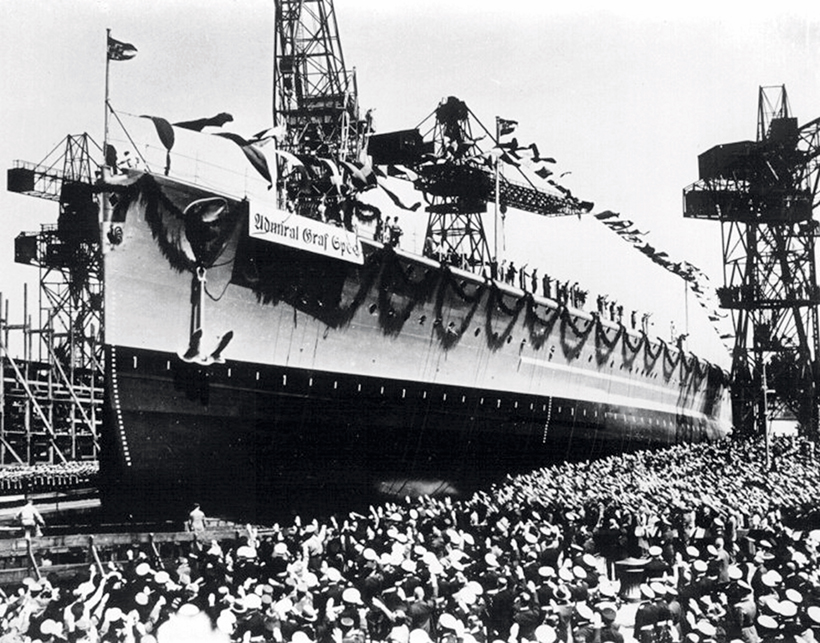

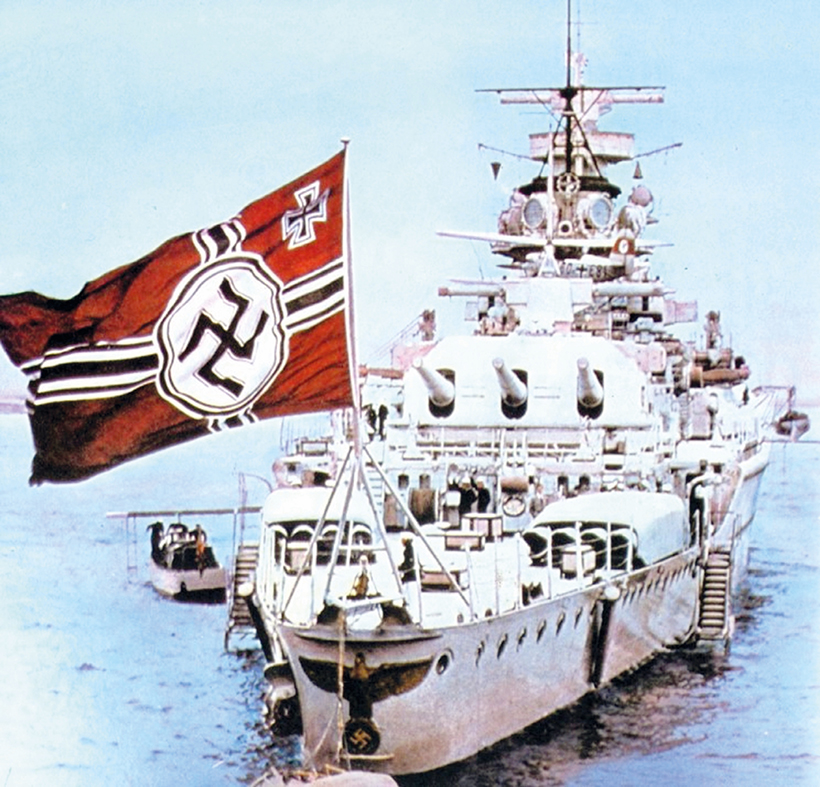

Graf Spee at her launch ceremony, on 30th June, 1934.

Graf Spee was 600ft overall and her design displacement was 14,890 tons standard, with a full load displacement of 16,020 tons, making a mockery of the official treaty limit of 10,000 tons. Propulsion came from four MAN nine-cylinder double-acting two-stroke diesel engines generating 54,000shp, and giving her a top speed of 28.5 knots. Six 11-inch SK C/28 guns mounted in two triple turrets provided her main firepower.

Graf Spee was constructed with a 3.9 in armour belt. She had one catapult, which was used to launch one of the two Arado AR 186 seaplanes carried for reconnaissance and spotting purposes. Graf Spee’s detection capability was also enhanced by the FMG G (gO) ‘Seetakt’ radar; she was the first ship in the German Navy to be so equipped.

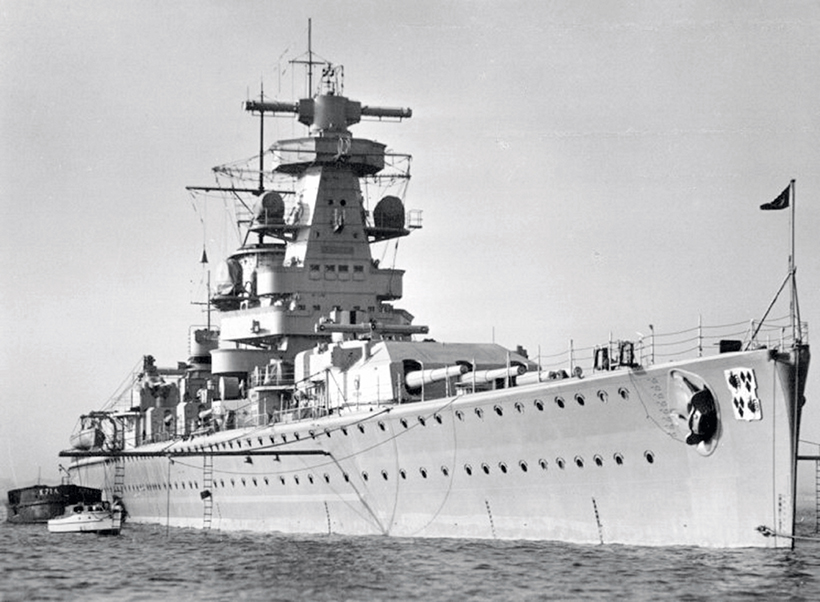

Graf Spee’s main armament comprised six 11-in chSK C/28 guns mounted in two triple turrets, one forward and one aft.

First duties

After commissioning in 1936 and following sea trials, Graf Spee became the flagship of the German Navy. She was tasked with carrying out patrols off the Republican-held coast of Spain. Graf Spee took part in the 1937 Coronation Spithead Review for King George VI, before returning to Spanish coastal waters. Just before the outbreak of World War II, in August 1939, Graf Spee sailed for the South Atlantic and ultimately her fate would be sealed there.

Graff Spee and others in the same class were known as ‘pocket battleships’ because of their speed and firepower.

Graf Spee attacked shipping in the South Atlantic using her radar, which assisted with ranging and had target detection as a secondary benefit. From the outset of World War II she was tasked with attacking Allied shipping. Initially, however, her Commander, Hans Langsdorff, would stop and search ships for so-called contraband, and then sink them, having ensured that all the crews had been safely evacuated. She was supported in this task by the German Navy supply ship Altmark.

In the early part of September 1939, Graf Spee avoided contact with Royal Navy ships, steaming away from a possible meeting with the heavy cruiser HMS Cumberland. The shackles were finally taken off Graf Spee on 26th September, when she was authorised to start seeking out and attacking Allied merchant shipping. It took only four days for Graf Spee to locate and sink the cargo ship Clement. She was not sunk, though, until her crew had been able to take to their lifeboats.

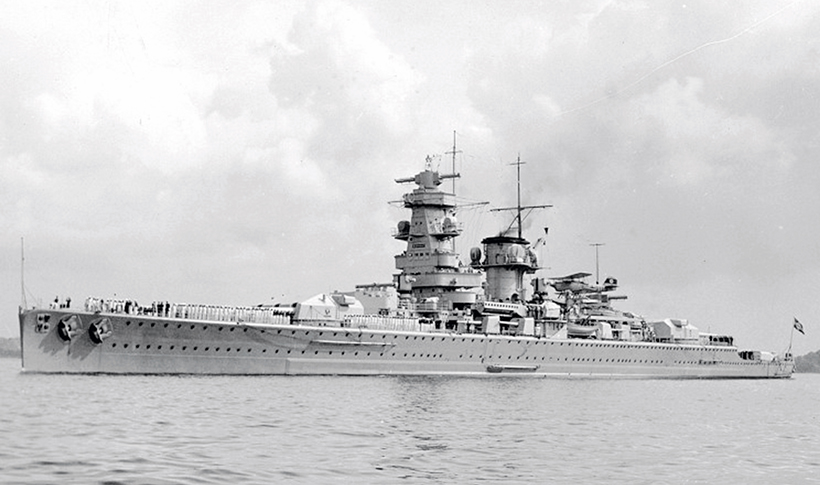

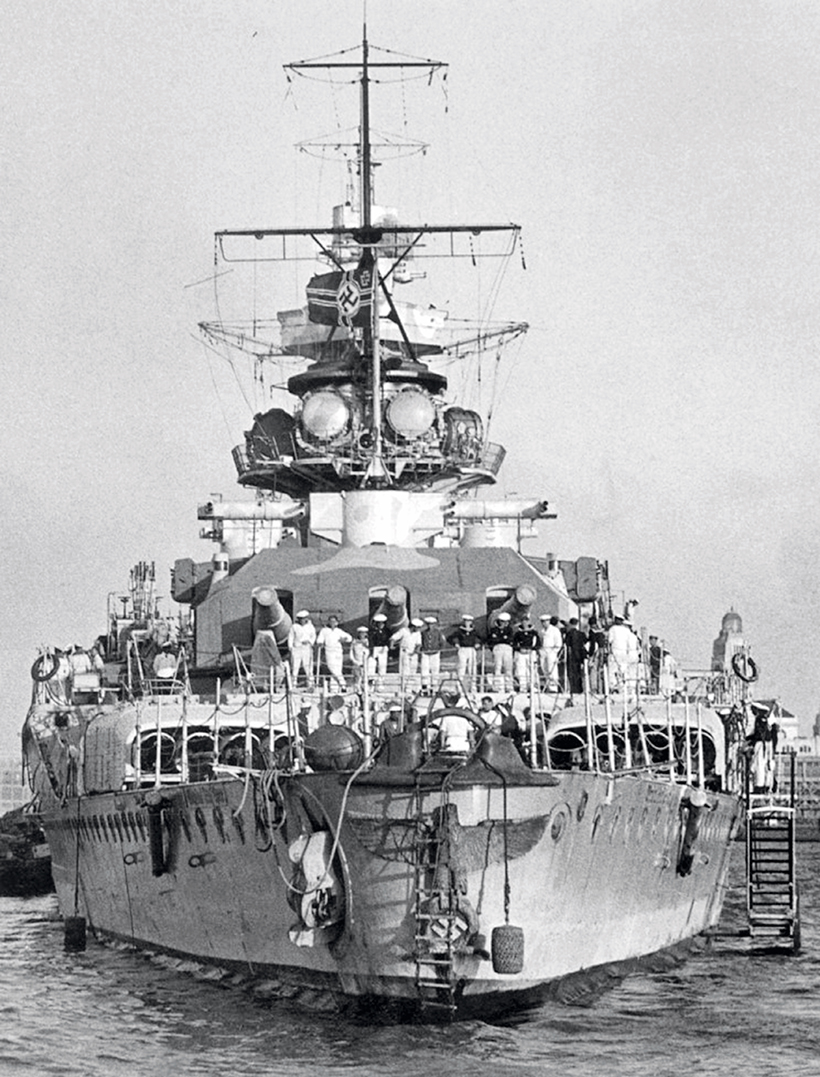

Graff Spee pictured at the 1937 Spithead Fleet Review for King George VI.

In response to the threat of Graf Spee, the Admiralty issued a warning to merchant shipping in the South Atlantic to make them aware that a German surface raider was operating there. Both the British and the French Navies sent their warships to attempt to track down and sink Graf Spee. The assembled ships included aircraft carriers, battlecruisers, cruisers and battleships, such was the perceived threat to shipping posed by Graf Spee.

Even while this formidable force was being assembled, Graf Spee was having more success against merchant shipping. The steamer Newton Beech was captured and used for a short period to house prisoners of war, steaming alongside Graf Spee. However, Newton Beech was too slow to keep up and Commander Langsdorff ordered her to be sunk and the prisoners to be taken aboard Graf Spee. The previous day – 7th October, 1939 – Graf Spee had sunk the merchant ship Ashlea.

Captain Hans Wilhelm Langsdorff commanded Admiral Graf Spee; born in 1894, he received the Iron Cross 2nd Class during World War I for his actions at the Battle of Jutland. He committed suicide in Buenos Aires.

On 10th October another steamer, Huntsman, was captured and used to transport prisoners until she and Graf Spee rendezvoused with Altmark. On 17th October the prisoners were transferred from Huntsman to Altmark, and Huntsman was sunk. Another steamer, Trevanion, was also sunk before the end of October, at which point Langsdorff ordered Graf Spee to sail for the Indian Ocean. His thinking was twofold; he was hoping that this action would divert the large number of warships in the South Atlantic searching for Graf Spee away from there and, secondly, to cause confusion among the Allies about what his intentions were.

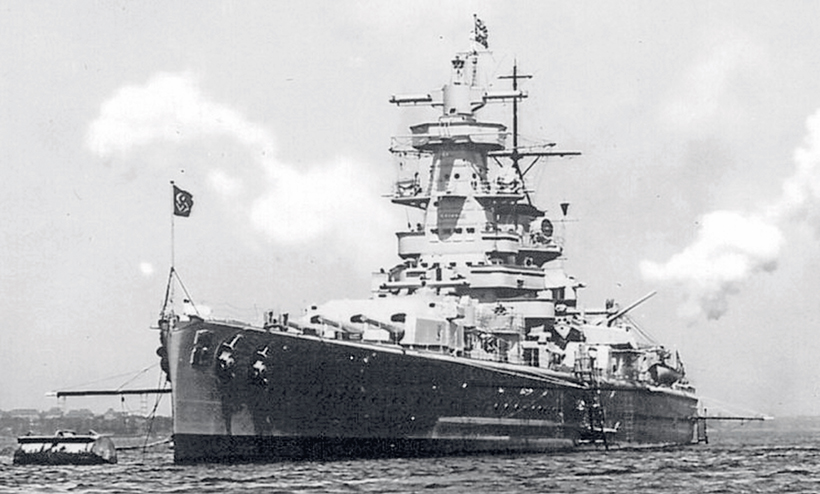

Admiral Graf Spee proved very successful, attacking and destroying Allied merchant shipping during her spree in the South Atlantic during 1939.

Even while doing this, Graf Spee still engaged and sank merchant shipping. The ship returned to the South Atlantic, in mid-November, for another meeting with Altmark to transfer prisoners. During this period, attempts were made to ‘disguise’ Graf Spee, by adding a dummy gun turret and another funnel. The idea was to change the silhouette of the ship to confuse the Allied ships which were searching for her.

Last victim

Graf Spee’s last victim was the freighter Streonshalh, which she sank on 7th December. Langsdorff, acting on information retrieved from Streonshalh, set sail for the coast off Montevideo. On 13th December, Graf Spee encountered British warships in the form of HMS Exeter and a number of cruisers. Langsdorff decided to engage, and he took Graf Spee’s crew to battle stations and closed in on the British ships at speed.

Graf Spee’s Eagle and Swastika crest was recovered from her wreck.

Langsdorff ordered Graf Spee’s main gun battery to be focused on HMS Exeter and the secondary guns on HMS Ajax and HMS Achilles. Commodore Henry Harwood, who was in charge of the British ships, ordered his ships to sail apart to split the gunfire from Graf Spee. In the battle that raged, and in just half an hour, Exeter was hit three times. Her two forward turrets were knocked out and her bridge and aircraft catapult were destroyed, and fierce fires broke out onboard.

Graf Spee at Montevideo, before her scuttling on 17th December, 1939.

Ajax and Achilles tried to divert the fire by sailing closer to Graf Spee. The ploy was partially successful, as Langsdorff, fearing a torpedo attack, laid down a smokescreen and broke off the engagement. This allowed Exeter to withdraw, with another gun turret out of action and a number of dead and wounded crew. Such was the importance of this battle, however, that Exeter returned to the fray, but further hits forced her final withdrawal.

Ajax then had her aft gun turrets put out of action and, after about two hours of gunfire exchanges, both sides broke off the action. Graf Spee headed for the River Plate estuary, while the British ships remained outside it to prevent her leaving. Both the British ships and Graf Spee had suffered damage and crew losses from this engagement. Langsdorff decided to head into Montevideo port to set down his wounded and dead crewmen, as well as to carry out damage assessment.

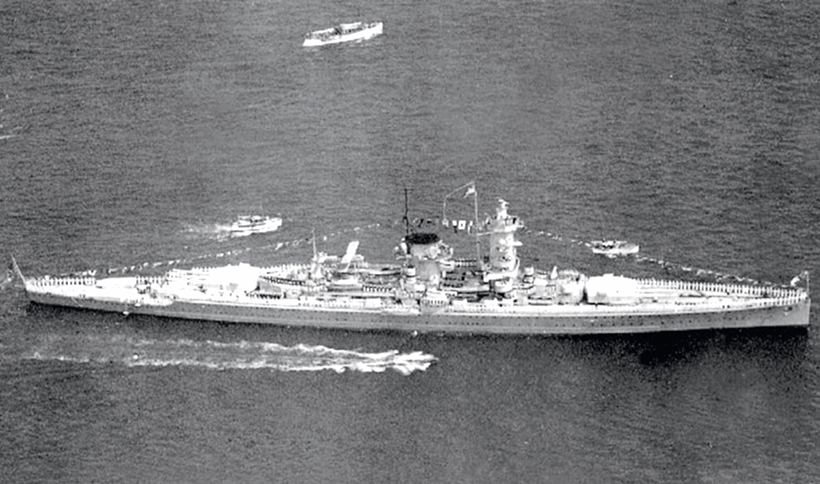

Graf Spee in the Kaiser Wilhelm canal, in 1938.

Superficial damage

Despite the intensity of the gunfire between the British ships and Graf Spee, she suffered only superficial damage. The worst of it was to Graf Spee’s oil purification plant, which was needed to prepare the diesel fuel for her engines. Her desalination plant and galley were also destroyed. Langsdorff knew that this damage would take at least a couple of weeks to make good and that, unless repairs could be effected, there was little prospect of Graf Spee returning to Germany.

At this stage, British Intelligence effectively fooled Langsdorff into thinking that a large force of British ships was moving into the area and would soon be in position to engage and destroy Graf Spee should she attempt to break out of the port. This led to discussions with his superiors back in Germany. There were few options available. He could try to break out and get to Buenos Aires, in Argentina. If this had been possible, then his ship and crew would have been interned there for the rest of the war. The other option was to scuttle Graf Spee in the River Plate estuary.

Although she was powerfully armed, Graf Spee avoided contact with Allied warships until the Battle of the River Plate.

Having discharged the wounded, dead and prisoners, and being unwilling to risk further loss of life to his crew, Langsdorff decided to scuttle Graf Spee. He had little choice given the amount of damage to his ship, and the fact that Uruguay was neutral but friendly with Britain, and they would probably have let the British examine Graf Spee once it had been interned there.

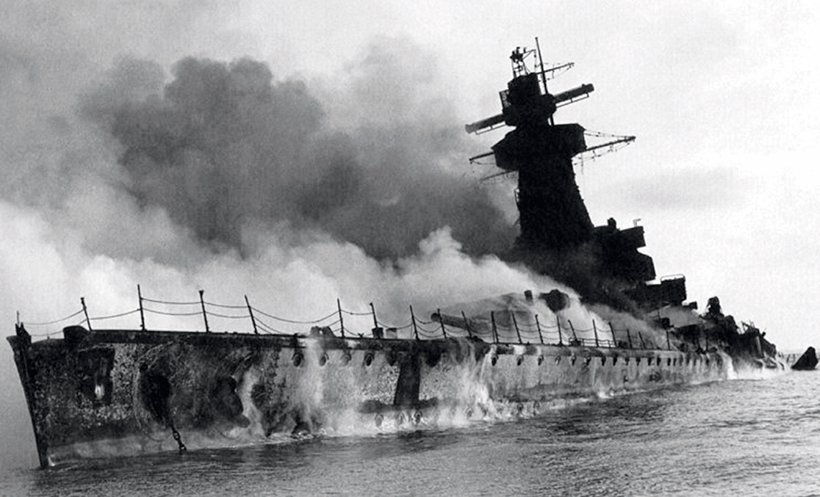

Graf Spee ablaze after her scuttling in the River Plate estuary.

On 17th December, 1939, Graf Spee left port and was scuttled, and Langsdorff ensured all the ship’s sensitive equipment had been destroyed. Three days later, in a Buenos Aires hotel, Langsdorff shot himself. His crew were interned in Argentina for the rest of the war. Between 1942 and 1943, the wreck of the Graf Spee was partially broken up, but much of it remained visible, as it lay in only about 36ft of water. Salvage rights, through a piece of subterfuge, ended up with the British, who used the information they gained from exploring her wreck to help discover how her guns had been so accurate.

The wreck of Graf Spee.

It took until 2004 for further salvage work to take place, as the wreck had become a hazard to shipping. This salvage saw her gunnery range-finding telemeter and – perhaps more controversially – the Eagle and Swastika crest of the Admiral Graf Spee being recovered. One can only speculate what impact Graf Spee might have had during World War II had her participation in it not ended at Montevideo.

This feature comes from a recent issue of Ships Monthly, and you can get a money-saving subscription to this magazine simply by clicking HERE

Previous Post

The Fordson Dexta is my passion!

Next Post

1926 Renault OS discovered 45 years ago, then restored