Digging for China clay

Posted by Chris Graham on 30th March 2020

David Vaughan looks at the fascinating range of historic machinery that was involved in digging for China clay in what was a major Cornish industry

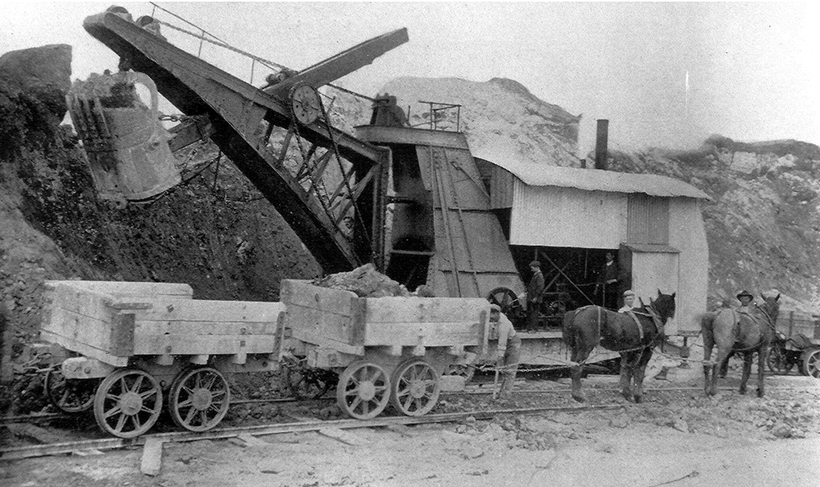

Digging for China clay: A Ruston Dunbar, believed ex-Manchester Ship Canal Co, in Dubbers Pit, c1908.

China Clay or, to use its correct name, ‘Kaolin’ is found in partially decomposed granite, an igneous rock which forms the prominent moorland Tors of Devon and Cornwall. The name Kaolin is probably derived from ‘Kao ling’ the Chinese for ‘high ridge’, because it was first found in the hills of Kiangsi province, in about AD 500. It was used to make high-quality porcelain, and the process remained a closely guarded secret until 1719, when it became known to the Western world, after which a search began for a suitable source in Europe.

William Cooksworthy, a Quaker chemist from Plymouth, prospected for the mineral and found a small deposit near Helston, and larger ones near St Austell. He took out a patent for the process of the manufacture of porcelain using ‘China’ clay, and opened a small pottery in Plymouth, in 1768. When the patent fell due for renewal in 1882, Staffordshire potters such as Wedgwood, Spode and Minton, took over the leaseholds of existing workings, and set up business in Cornwall.

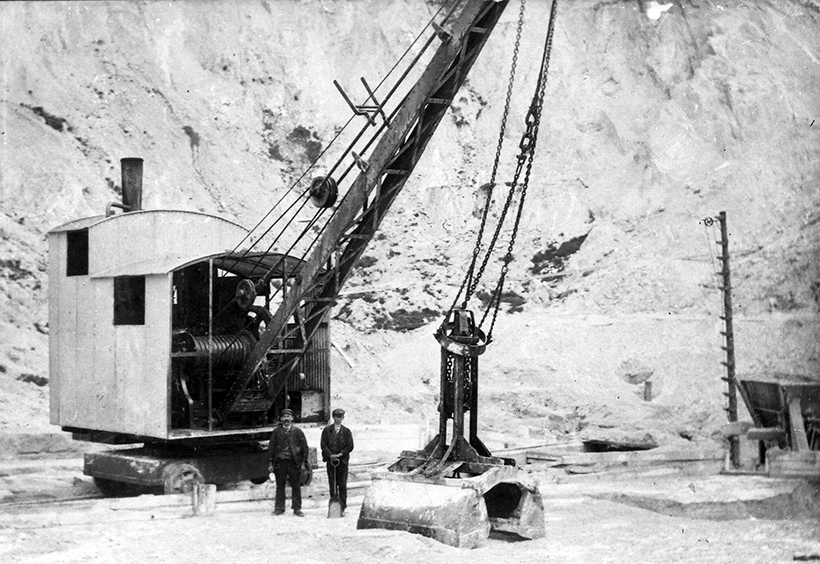

A 12hp Ruston steam navvy with a clamshell grab, also at Dubbers Pit.

Local operators

Although some of the earlier clay pits were operated by the Staffordshire potters, by 1840 most of these had withdrawn from this part of the industry, to concentrate on the design and manufacture of fine porcelain. This left the extraction and preparation of the clay to the Cornish, whose operations were undertaken by small mining consortiums known as ‘Adventurers’. By 1845, nearly 50 pits were being worked and, by the 1870s, some 120 small enterprises were engaged in the industry, producing 65,000 tons annually.

The early 20th Century saw some consolidation, but there were still around 70 companies all competing for the same market. Competition was fierce, corners were cut and there was little in the way of capital investment or product development. Working conditions were poor and wages were low. The First World War saw a large proportion of the workforce enlisted in the armed forces, and demand for fine china fell away, resulting in over capacity.

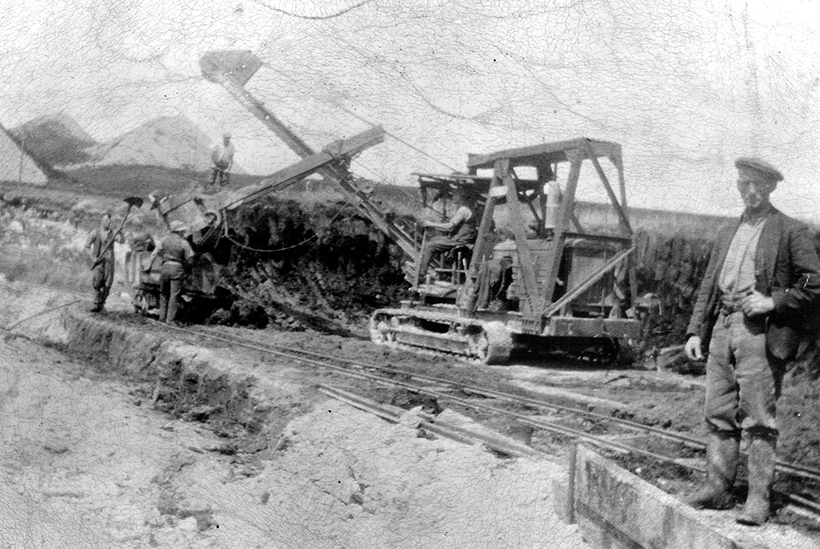

A Ruston No.3 Universal petrol-engined excavator. The jib could be slewed and was capable of being fitted with all types of bucket. It’s seen here working at Great Treverbyn.

As a direct result of this, April 1919 saw the amalgamation of three of the largest producers; Martin Bros, The West of England China Clay & Stone Co and the North Cornwall China Clay Co. Together, these three formed English China Clays (ECC), which accounted for around half of the industry’s output at the time. Soon after this, the firm of HG Pochin acquired JW Higman, taking it to third place in the industry, after ECC and Lovering China Clays.

During the inter-war years, despite China Clay becoming a major supplier to the paper industry (as a whitener for newsprint), the industry’s output fell by a third, and ECC started losing money. The solution was a merger between the three leading companies, with ECC as a holding company for a new operating company – English Clays Lovering Pochin.

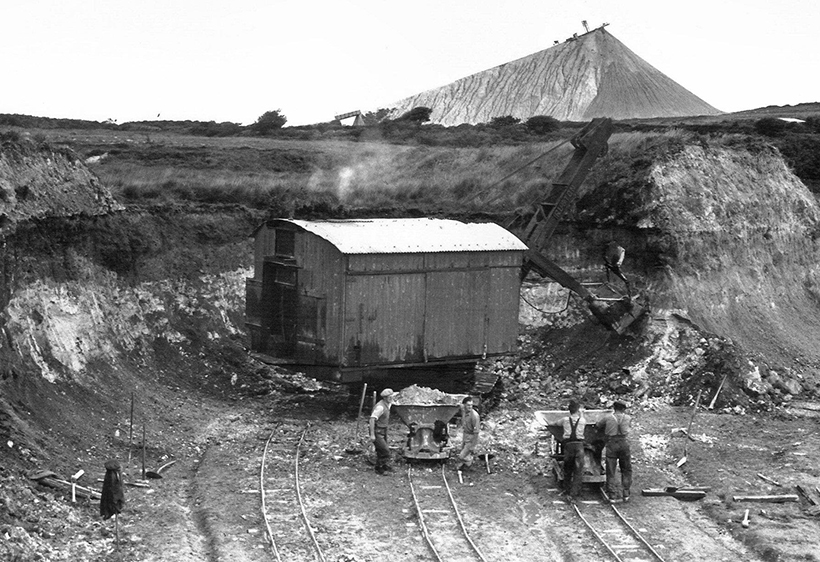

A Ruston No.10 oil-engined shovel, at Melbur Pit, loading V skips.

Thorough overhaul

In the early 1950s, ECC acquired full ownership of the operating company, which resulted in a thorough overhaul of the business and created four operating divisions. These were: China clay (production and sales); building; quarrying; transport. This restructuring brought huge benefits in efficiency and production, and put the whole industry on a firm footing.

Until this re-organisation, the providers of quarrying and earthmoving plant – as well as internal and external road transport – had been shared by various small concerns, each with their own, varied fleets, depots and maintenance facilities. The increased size of the pits, some up to 400 ft deep, and their associated waste tips, meant an ever-increasing need for more and larger plant and machinery. So, in 1952, the company sub-division ‘Western Excavating’ came into being, alongside pit-to-port haulage by the ‘Heavy Transport Co’ and countrywide haulage by ‘Western Express’, with its fleets of tippers, rigids and artics in a familiar blue and white livery.

Par Harbour in 1963, showing Western Excavating cranes used to load ships. Par was a main point of shipment for China Clay along with Fowey and Charleston, and was also home to the little Bagnall saddle tanks, Alfred and Judy, now preserved at the Bodmin & Wenford Railway.

‘Western Excavating’ was, at one time, believed to be the largest, individual operator of earthmoving plant in the UK and, over the years, operated plant from all the major manufacturers, including Ruston-Bucyrus, Euclid, Michigan, Bray and Caterpillar, alongside many other well-known makes. At one time, it operated one of the largest fleets of Foden dumpers in the UK and manufacturers, seeing the potential of profitable sales, were always keen to send demonstrators of their latest earth-movers or dumpers for trials.

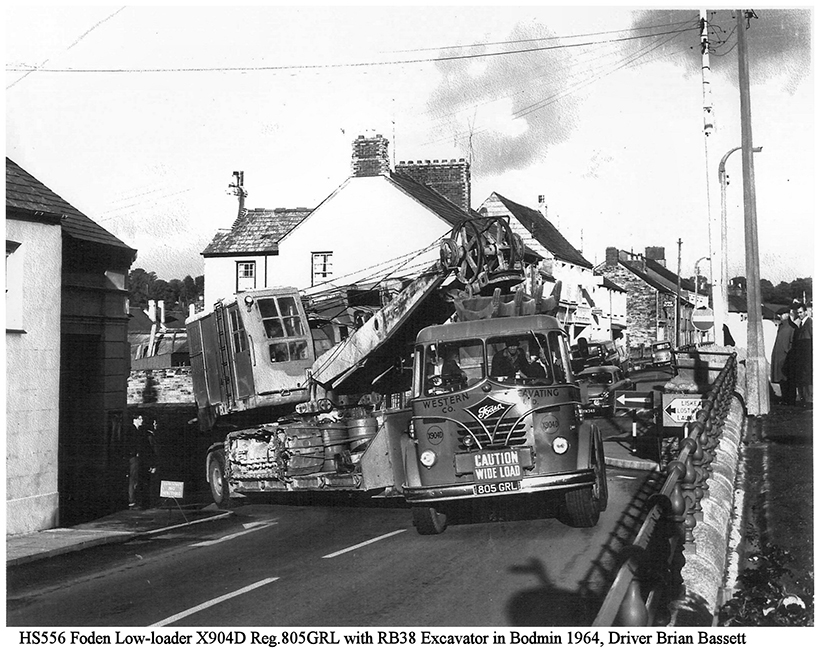

Western Excavating’s Foden S20, with low-loader and 38RB excavator, threads its way around a tight corner in Bodmin.

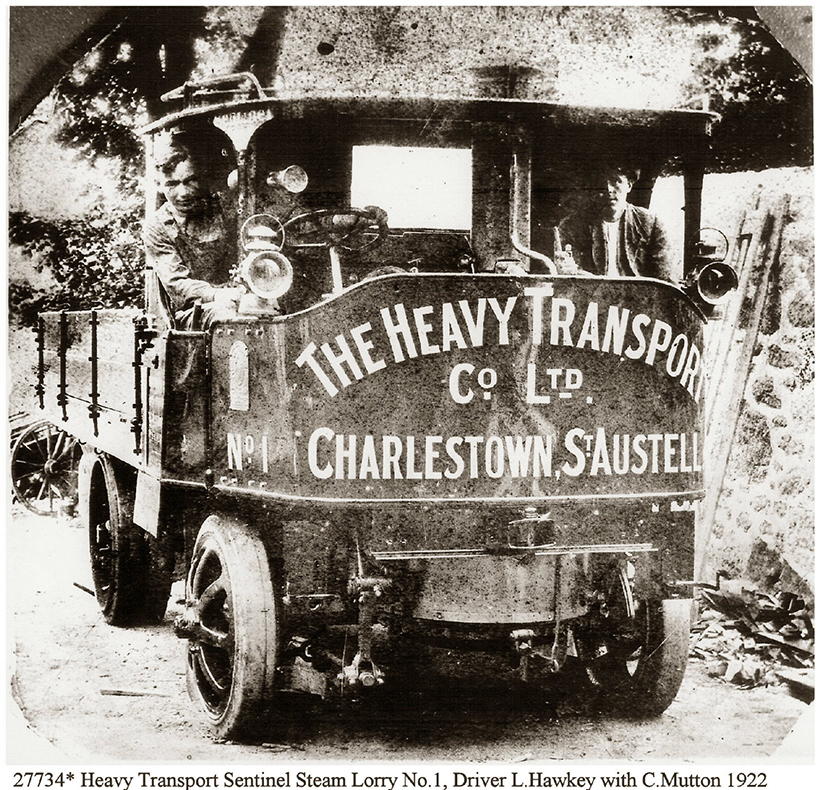

The photographs included here show some of the early excavators used by some of the smaller operators, before the formation of Western Excavating, and working with various tippers and dumpers. Haulage to the docks at Par and Charleston was undertaken by horse and wagon until the First World War, but some companies had already started to use steam lorries and a small selection of these is also included.

I’m grateful to The China Clay Heritage Society and Wheal Martyn Museum, for the use of photographs from their archives, and to Ivor Bowditch, ECC’s communications manager, (now retired) for his help.

This posed publicity shot shows the large fleet of Foden dump trucks, with some of their drivers. Note the various styles of cab and dumper bodies.

No. 1 in the fleet of Heavy Transport, then based at the port of Charleston, was this Sentinel waggon. The firm became the main haulier for ECC, and its lorries could be seen all over Cornwall, and further afield, until the 1990s.

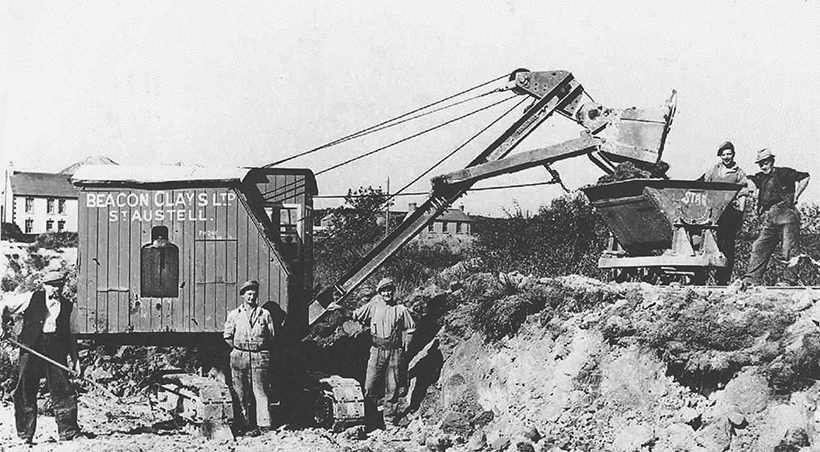

This Priestman Cub was operated by Beacon Clays of St Austell, one of the companies later absorbed into ECC. It’s seen loading a rather battered Dodge tipper, with a Muir Hill dumper in the background.

Another Beacon Clays Priestman, this time loading a Hudson V skip on temporary, 2ft-gauge track.

This photo illustrates the conditions at the clay pits. The clay is being washed out with a high-powered water jet, down to the sump where it’s separated from the sand/mica. A 22RB is loading a Foden six-wheel dumper with non-clay-bearing rock.

A Ruston 10RB, newly-painted in Western Excavating orange livery, photographed just after the division was formed. It’s preparing to load a couple of Bedford OW dumpers that had probably been converted from former military vehicles.

A 38RB face shovel loads a Foden FE six-wheel dumper. Nominally rated at 9cu/yd, these often worked with higher payloads. Western Excavating operated the largest fleet of Foden dumpers in the 1950s.

Another Ruston-Bucyrus 38RB, seen here loading a Euclid R15 dumper – similar to the Dinky Supertoy version, but with a flared-sided quarry body.

This Smiths of Rodley shovel is loading a Bedford O series short wheelbase tipper, belonging to Rawlings of St Mawgan.

To subscribe to Old Glory magazine, simply click here