Royal Navy changes over the past 70 years

Posted by Chris Graham on 26th April 2023

Paul Brown takes time to assess the significant changes made to the Royal Navy during the second Elizabethan age.

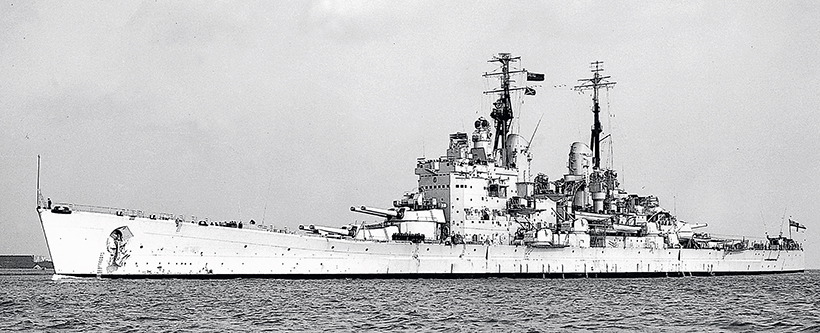

The Colossus class aircraft carrier Ocean. Her aircraft flew 7,964 sorties during the Korean War. Her Sea Furies were attacked by eight MIG15s, with one or possibly two MIGs downed, the only occasion when a piston-engined aircraft has shot down a jet.

Over the course of the 70-year reign of Queen Elizabeth II, the Royal Navy changed out of all recognition. Its status as a superpower navy with worldwide bases and operations was eclipsed, but it remained a powerful force because of its potency, if not its size.

The first four decades were dominated by the Cold War, while the wars and conflicts during the whole era included the Korean War, the Suez invasion, the Indonesian confrontation, the Cod Wars, the Falklands War, two Gulf Wars, the Balkan wars and the Libya crisis.

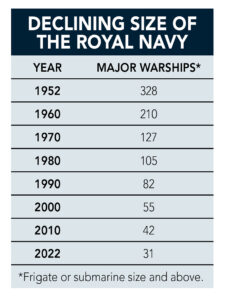

In 1952 the UK was still a global and maritime superpower with a large empire. It had the world’s second largest navy, the largest shipbuilding industry and the largest merchant fleet. The vast networks of seaborne trade routes linking dominions, colonies, and traditional trading partners (such as in South America and the Middle East) were policed by a Navy whose size and versatility meant that it was able to engage independently in most types of conflict. It operated 328 warships of frigate or submarine size or above, of which 147 were in reserve, and had over 400 smaller ships.

The last British battleship, Vanguard, served in the Mediterranean and Home Fleets in the early 1950s, and headed the lines at the 1953 Coronation Fleet Review. She was reduced to reserve in 1955 and scrapped in 1960.

Squadrons were distributed among five overseas fleets and stations, as well as in home waters. The home dockyards of Chatham, Devonport, Portsmouth, Rosyth and Sheerness were augmented by overseas dockyards in Malta, Singapore, Trincomalee and Simonstown, and bases at Portland, Harwich, the Clyde, Londonderry, Bermuda, Bahrain and Hong Kong.

Seventy years later, in 2022, the UK’s superpower role was much diminished, and its empire gone. The nation’s shipbuilding industry and merchant fleet were shadows of their former selves. There had been a dramatic reduction in the size of the Royal Navy, and its status as a major navy, with worldwide operations, had been lost. Spending on defence had diminished from 11% of GDP (in 1952) to 2.5%.

The big Navy

In 1952 the two big fleets, Home and Mediterranean, would deploy on several cruises a year, visiting the more exotic and attractive ports. It was different in the Far East because the Korean War was on, so a substantial fleet, including aircraft carriers and cruisers, was engaged in patrols and combat off the Korean coast.

The CO class destroyer Cossack served in the 8th Destroyer Squadron on the Far East station during the 1950s. During the Korean War she patrolled off the west coast of Korea as part of the allied task force.

In February 1952 British warships on station in the Korean War theatre included the aircraft carrier Glory, the maintenance carrier Unicorn, the cruisers Belfast and Ceylon, the destroyers Charity, Cockade, Concord, Constance and Cossack, the frigates Alacrity, Cardigan Bay, Mounts Bay and Whitesand Bay, the hospital ship Maine, and the headquarters ship Ladybird. The aircraft carrier Warrior was employed in carrying troops, replacement aircraft and stores from the UK to Singapore and Japan.

In all, 34 Royal Navy warships (including four aircraft carriers and six cruisers) took part in the war, as well as 16 RFAs, one hospital ship, nine Royal Australian Navy ships (including one aircraft carrier), eight destroyers of the Royal Canadian Navy and six frigates of the Royal New Zealand Navy. The Cold War was intensifying, with the USSR building up a large submarine fleet, and it seemed that the Atlantic might again become a theatre of conflict. Thus, the role of NATO, in which the UK was second only to the USA, was becoming more important, with exercises conducted regularly by multilateral forces.

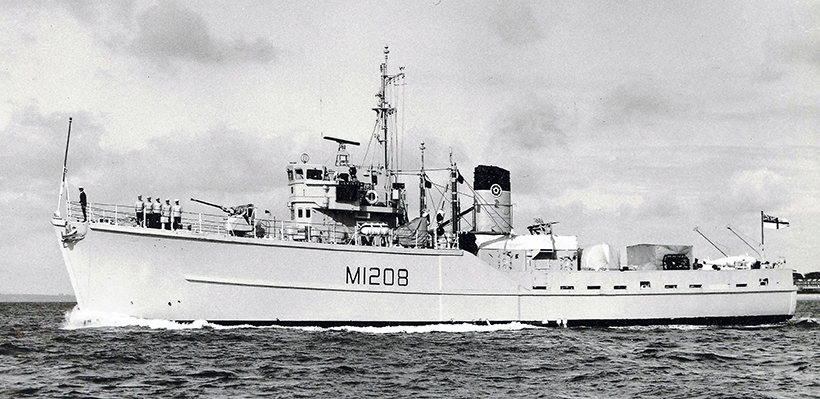

Completed in 1960, Lewiston was the last of 116 wooden-hulled Ton class minesweepers built for the Royal Navy. She is seen in her original form, with an enclosed bridge, one 40mm gun and twin 20mm guns.

Royal Navy personnel totalled 153,000 in 1952, and no women served at sea. This compared with 33,750 in July 2022, when women, who made up 11 per cent of personnel, were serving in both surface ships and submarines. Most of the ships serving in 1952 had been built during World War II, but there was still a small contingent of pre-war ships, including cruisers and auxiliaries. The surface warships were mostly steam-powered: steam turbines in the larger ships (from destroyer size up) and steam reciprocating engines in many frigates and most smaller ships.

The armament of these ships comprised guns, torpedoes and anti-submarine mortars. Sensor outfits, including radar, sonar and high-frequency direction finders, were fairly rudimentary. The era of the battleship had been eclipsed, with just Vanguard remaining in service. Submarines were diesel- and electric-powered and armed with torpedoes and, in some cases, a gun.

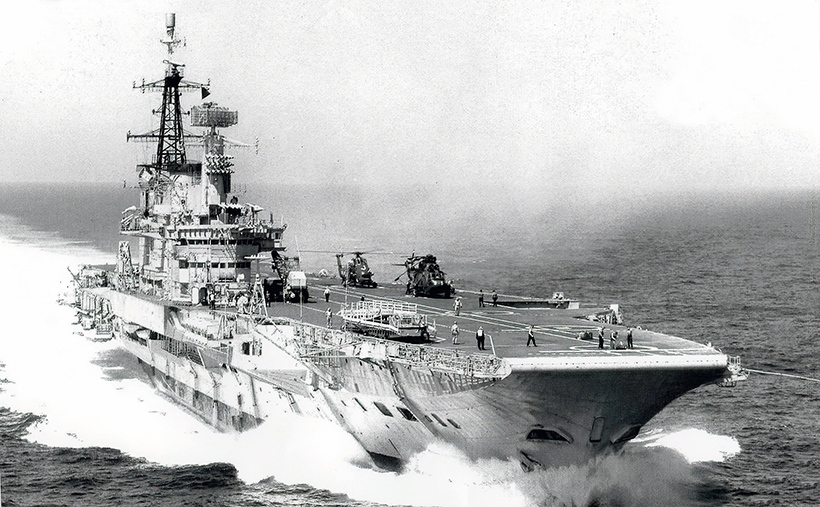

In the 1960s the newly upgraded Far East Fleet became more important, at the expense of the Mediterranean Fleet. In 1963 there was a rapid build-up in naval forces to deal with the Indonesian infiltration of Malaysia: the aircraft carriers Ark Royal, Eagle, Victorious, Centaur and Hermes and commando carriers Albion and Bulwark were all deployed, in a conflict which lasted three years.

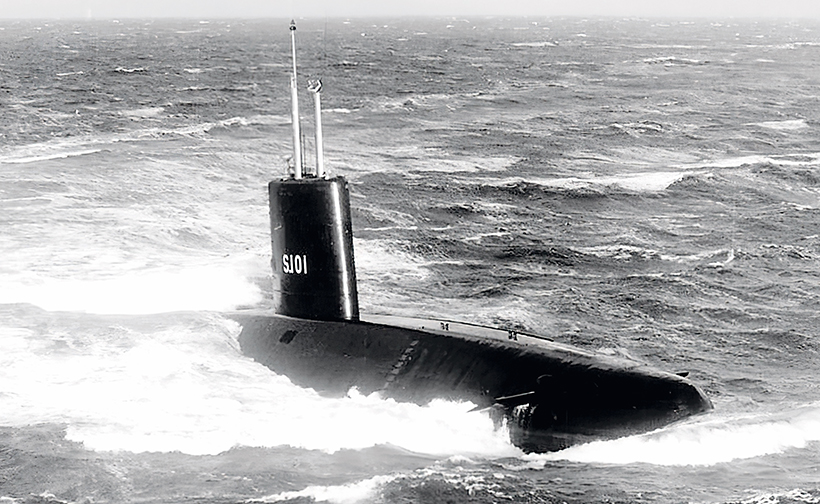

Dreadnought was the first British nuclear-powered submarine and was completed in 1963. She had a submerged speed of 28 knots and a surface speed of 20 knots. In March 1971 she became the first British submarine to surface at the North Pole.

RN ships employed during the conflict included five aircraft carriers, two commando carriers, one cruiser, four guided missile destroyers, six other destroyers, 16 frigates, seven submarines, 18 minesweepers, four seaward defence boats, and six other warships, as well as RFAs. By early 1965 the Far East fleet consisted of some 80 ships, including RFAs and Commonwealth Navy warships, an all-time high, and the largest fleet in the Navy, headed by the carriers Victorious and Eagle.

Falklands and after

The 1982 Falklands war presented the biggest challenge to the RN during Elizabeth’s reign. A large task force was sent to the South Atlantic to reclaim the islands that had been invaded by Argentina. The conflict lasted 72 days and claimed the lives of 236 British and 649 Argentinian servicemen, plus 19 British civilians from the Merchant Navy, and RFA and islanders. It was the largest naval and air combat operation between modern forces since the end of World War II. Reclaiming the islands was a remarkable achievement for the British forces, which had had to organise an 8,000-mile logistical train, and were pitched against powerful and determined air forces. The Royal Navy lost five ships: the destroyers Sheffield and Coventry, the frigates Ardent and Antelope, and the landing ship Sir Galahad, as well as the requisitioned transport Atlantic Conveyor. There were many lessons learned from the conflict, perhaps the most important being the need to improve radar and weapon systems (and the training of their operators) to enable them to cope more effectively with fast sea-skimming missiles like Exocets, fast and low-flying aircraft over sea and aircraft flying low over land.

The Leander class frigate Argonaut was modernised in Devonport Dockyard in the late 1970s and equipped with Exocet missiles. In the Falklands conflict she was damaged by two bombs dropped by Argentinian Skyhawks. (Pic: Crown Copyright/OGL)

The requirement for effective close-in weapon systems, as a last-ditch defence against aircraft and missiles which got through the outer rings of defence, was also highlighted. Many of the cuts planned in the 1981 Defence Review were reversed, allowing the Navy to keep all three Invincible class aircraft carriers and the two Fearless class assault ships.

The Cold War threat shaped the Navy until 1990, and helped ensure that the fleet was maintained at a reasonable size in the 1970s and 1980s. After that the ‘peace dividend’ led to frequent ‘salami slicing’ of the fleet’s size. The threat from Russia was returning 20 years later, its military collapse having been reversed since 2008, with massive increases in defence spending. The start of the Ukraine war in 2022 may have marked the start of a new cold war, and has revitalised NATO and European security consciousness and had a unifying effect on the West.

Overstretch

By 2022 the fleet was reduced to 31 warships of frigate or submarine size or above, which included two large strike aircraft carriers and the strategic nuclear deterrent of four Trident-armed submarines. The Navy had a much-reduced capacity to protect trade routes, its commitment in the Persian Gulf being a rare example of this.

Devonshire, the lead ship of the County class guided missile destroyers, was equipped with Sea Slug and Seacat air-defence missiles. She is seen during her second commission, when she was deployed to the Far East, 1965-66.

Having long since retreated from its powerbase in the Indo-Pacific regions, the Navy was now trying to re-establish a modest presence there, with two patrol ships on station and periodic task group deployments to the area. This reflected concerns about the growing military might of China, which was seen as a potential and formidable threat to global security.

The Navy’s NATO role in the eastern Atlantic remained a dominant commitment. An RN presence in a few small British Overseas Territories was still required – in Gibraltar, the Falklands and the Caribbean. The Navy could not mount an independent operation of the size seen in the 1982 Falklands conflict, not least because it lacked the numbers of surface escorts and submarines required. Thus, in any major conflict, it would have to rely on its allies to complement its resources.

The aircraft carrier Hermes served as a helicopter carrier in the seventies. She had been completed in 1959, being equipped with a fully-angled flight deck, steam catapults, mirror landing aids and Type 984 radar. (Pic: Crown Copyright/OGL)

However, what it lacks in numbers of ships the Navy partly compensates for through the potency of its forces, which include two large aircraft carriers and nuclear-powered submarines, which can launch nuclear-armed ballistic missiles or cruise missiles and torpedoes, and it has managed to cling on to an amphibious warfare force. There is, however, a need for more escorts and attack submarines to make a balanced force.

Guided missiles are now the main armament of the larger surface ships and are complemented by guns, homing torpedoes and helicopter-borne weapons. Sensors and systems, such as radar, sonar and electronic warfare systems, are highly sophisticated and complement the computerised automated weapon systems.

The aircraft carriers Prince of Wales (foreground) and Queen Elizabeth were assembled at Rosyth and commissioned in 2017 and 2019 respectively, replacing the three smaller Invincible class carriers. (Pic: Crown Copyright/OGL)

Most of the larger surface ships have gas turbine propulsion, and all the submarines are nuclear-powered. The ships are of varying ages: some Type 23 frigates, the remaining Trafalgar class submarine and the Hunt class minehunters are over 30 years old. Replacement of ships and submarines with new vessels comes at a glacial pace, with craft often being delivered years behind schedule, as with the Astute class submarines. If the seventh and last boat is completed on time in 2026, the commissioning of the class will have been spread over 16 years.

The first Type 26 frigate, Glasgow, will have taken ten years to build if it is completed on schedule in 2027, and the last of the eight ships will not be completed until 2037. The last of five Type 31 frigates, ordered in 2019, will probably not be completed until 2030. The current minehunters, which double as patrol vessels, are not being replaced with ships capable of such roles, but instead autonomous systems are being deployed in small launches. Thus, the number of seagoing ships is being further reduced.

The Swiftsure class nuclear submarine Sceptre in the Clyde area in 1996. She was commissioned in 1978 and served until 2010. In 1981 she suffered extensive damage in a collision with a Soviet submarine. (Pic: Crown Copyright/OGL)

Government talk of a bigger Royal Navy has yet to translate into anything tangible. After more than 70 years of steep decline any increase in size seems likely, at best, to be very modest. Five more frigates, of Type 32, was the stated aim by the mid-2030s, but the funding for both these and the planned multi-role support ships has now been suspended. We can only ponder what the next 70 years will bring, not just whether the Navy will be bigger or smaller, but what the effects of technological change will be, with modular shipborne systems, unmanned aerial, surface and submarine vehicles, laser weapons, electromagnetic rail guns and hypersonic missiles already in the development stages.

This feature comes from the latest issue of Ships Monthly, and you can get a money-saving subscription to this magazine simply by clicking HERE

Previous Post

How about a classic ULEZ city beater?

Next Post

Important alternative fuel trials update for steamers