Ruston steam shovels

Posted by Chris Graham on 3rd May 2021

Keith Haddock continues his A-to-Z of excavation equipment with a fascinating look at the extensive range of Lincoln-built Ruston steam shovels.

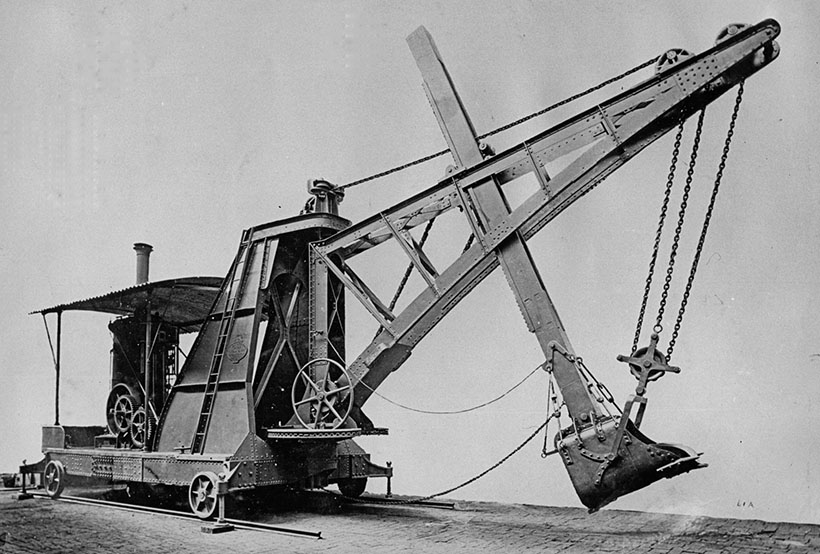

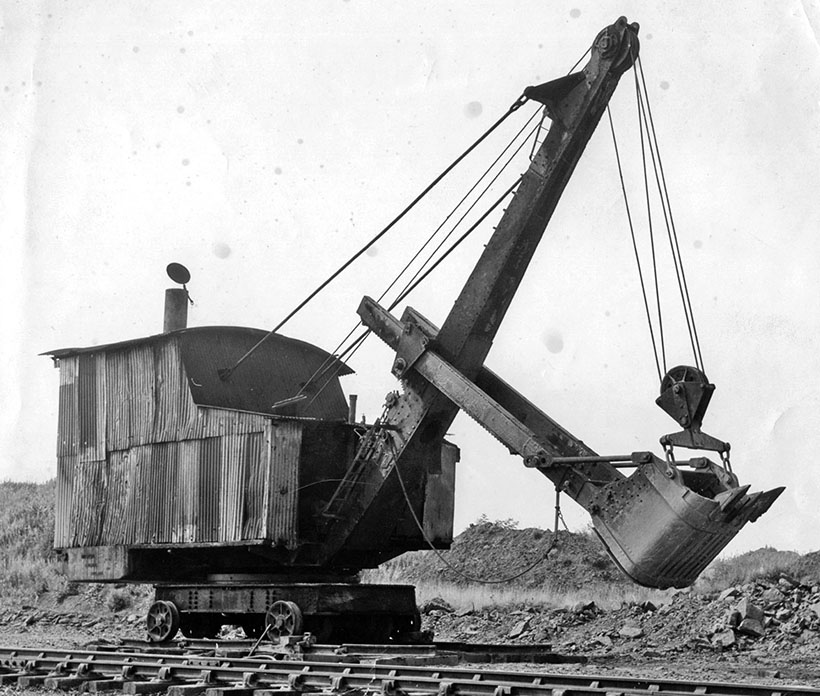

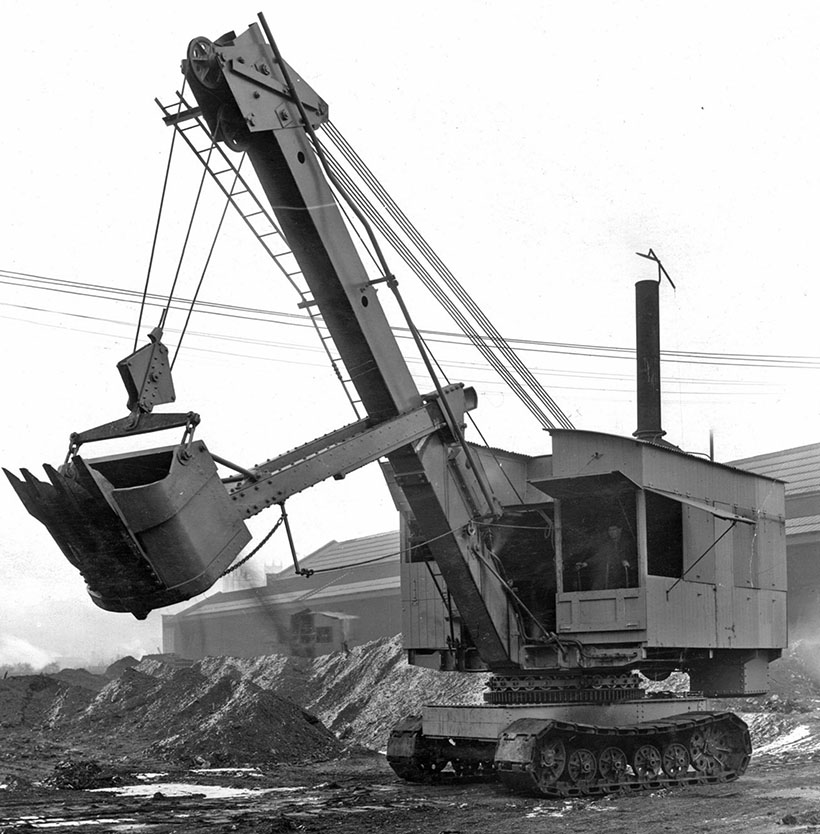

Ruston steam shovels: The first steam navvy built by Ruston, Proctor & Co was this Ruston-Dunbar, in 1874. Notice the hand wheel to operate the crowd motion!

The excavator business at Lincoln traces its roots back to 1857, when an enterprising 22-year-old called Joseph Ruston became an equal partner in the firm Burton & Proctor, which was already established in the town. That same year, Ruston purchased Burton’s share, and the new firm became known as Ruston, Proctor & Co.

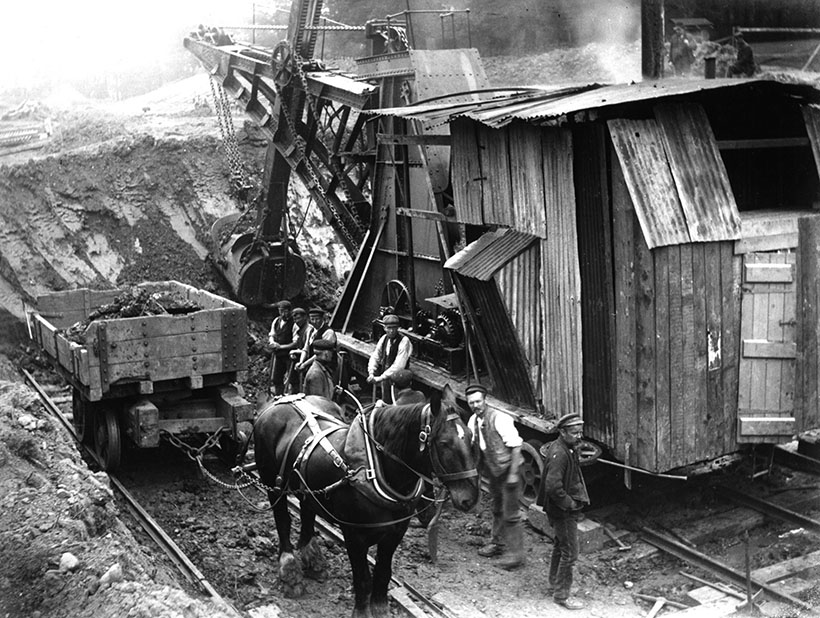

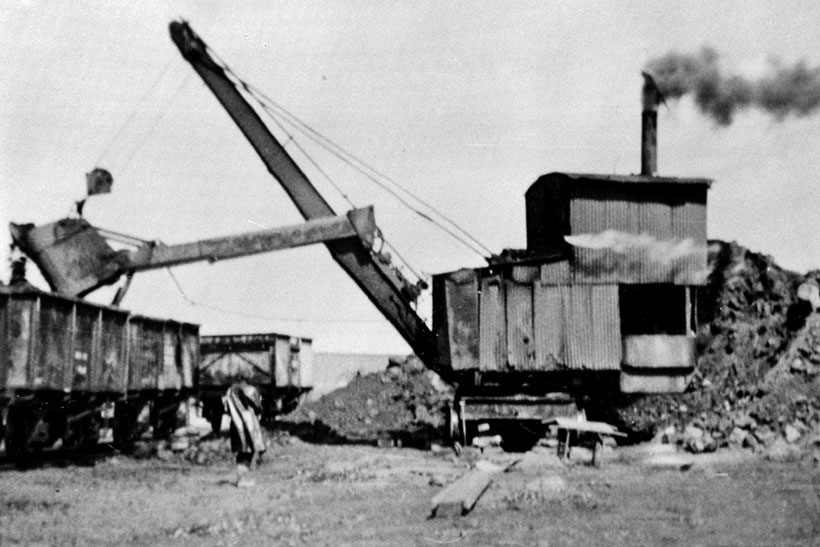

A Ruston steam navvy working at Wembley Park, during construction of the Great Central Railway.

Under Joseph Ruston, this firm rapidly expanded, manufacturing all manner of steam engines, boilers, agricultural machines and implements. By the time Proctor retired in 1864, employees numbered several hundred. In 1874, the company saw a commercial opportunity to add excavators to its existing product range, by purchasing the patent for a steam shovel designed by James Dunbar. As a result, the first Dunbar-Ruston Steam Navvy appeared the following year.

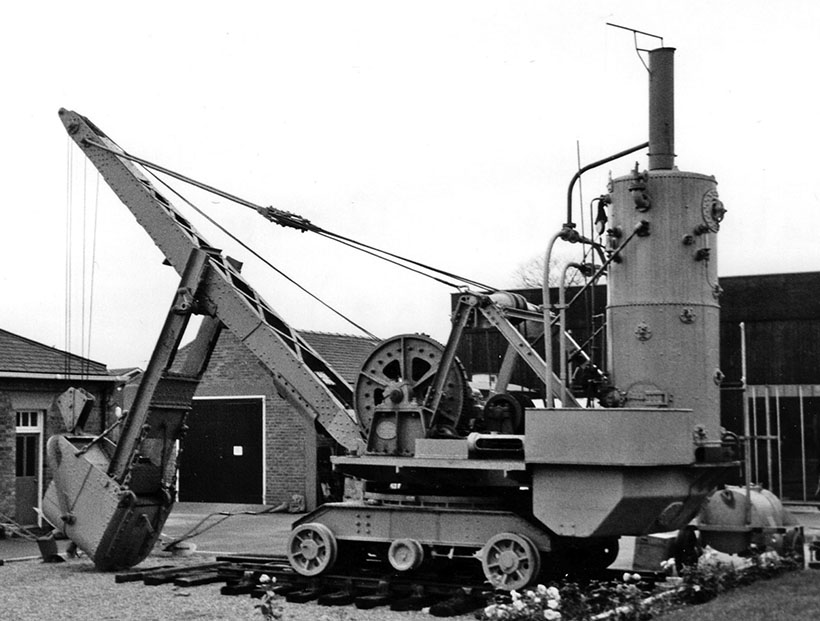

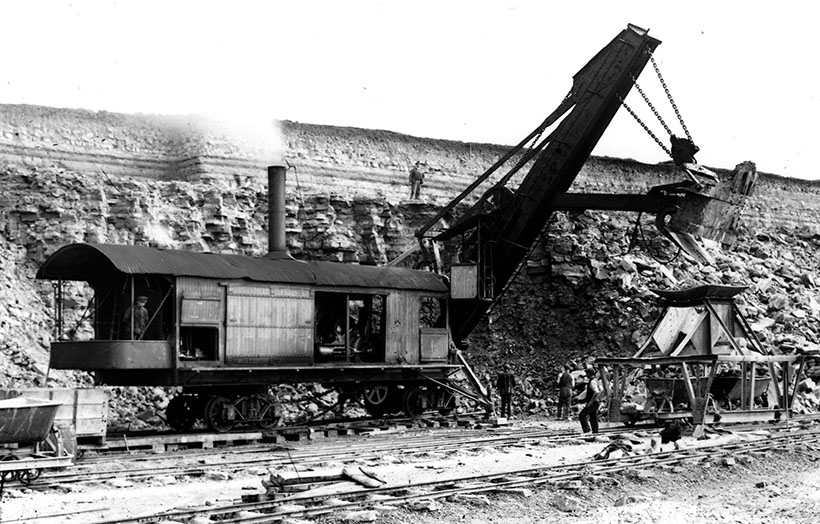

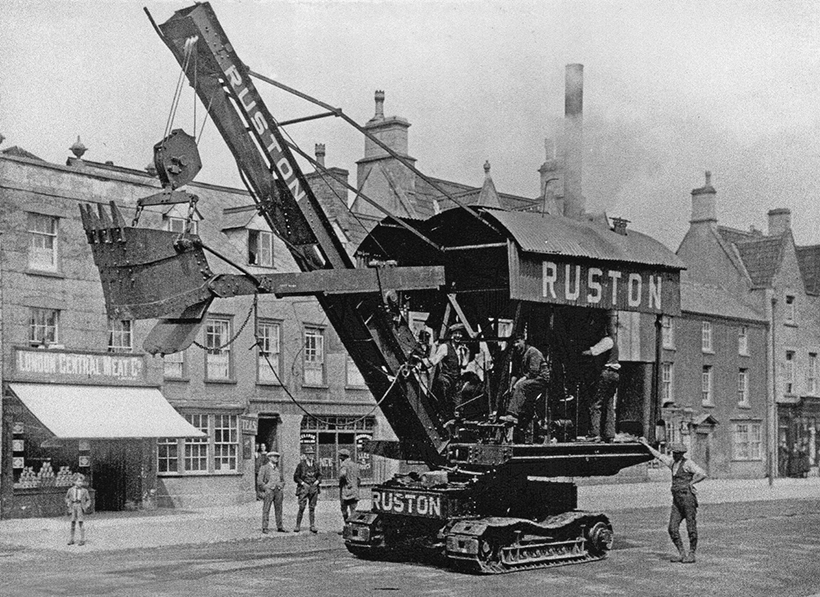

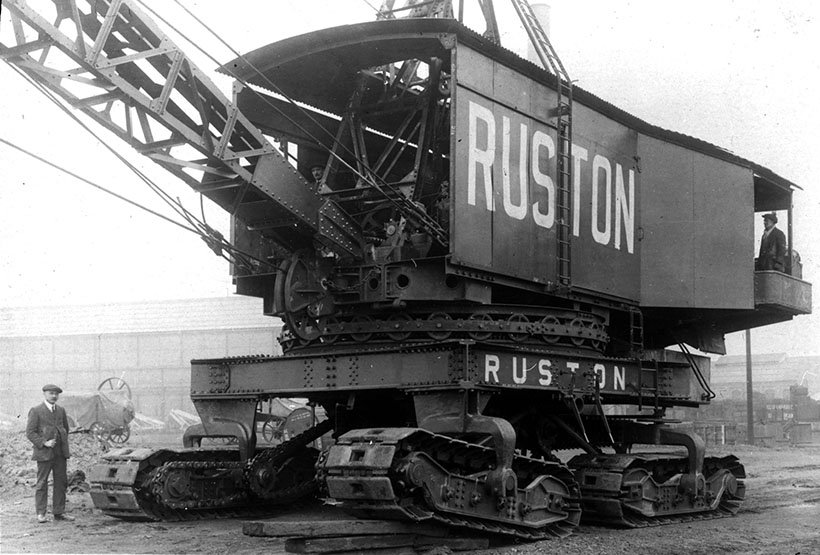

The Ruston Proctor ‘12-Ton Crane Navvy’ built 1909 and preserved at the Museum of Lincolnshire Life by Ray Hooley. First appearing in 1902, it was the company’s first, fully-revolving shovel.

The first of many

The original machine weighed some 22 tons, carried buckets of 1-1½ cubic yard capacity, and was powered by a standard, Ruston 10hp double-cylinder steam engine. It was claimed to be the first land excavator built by a British company. The machine was on rails with boom and shovel attachment mounted on the front of the carriage. It was able to swing about 200 degrees, in similar fashion to the earlier, American-built Otis excavators.

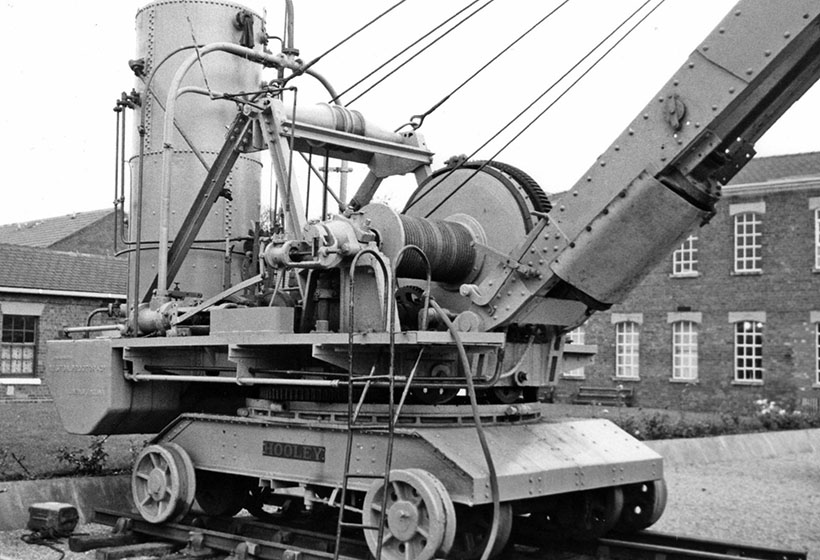

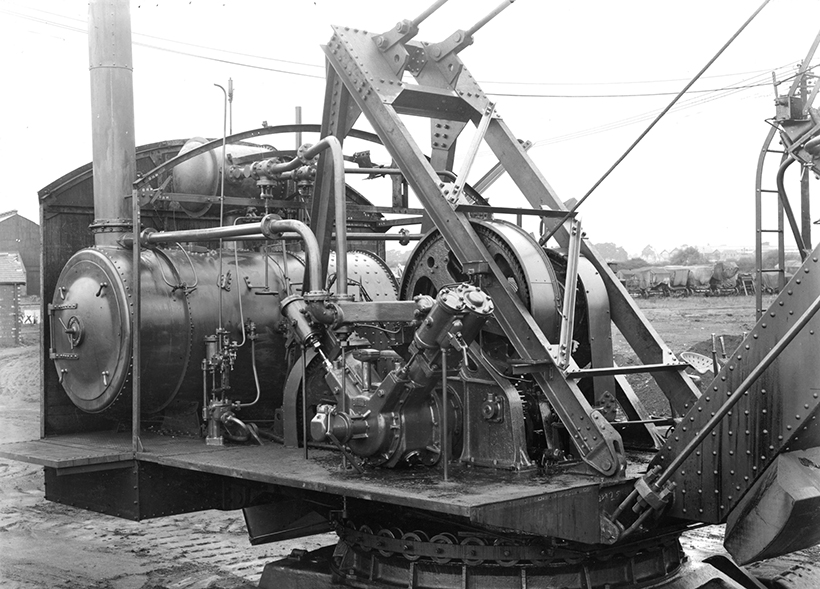

A Ruston Proctor ‘12-Ton Crane Navvy’ showing the draw works and boom-mounted steam cylinder, to operate the crowd mechanism by rack and pinion.

While the hoist and swing motions were powered by the steam engine, the crowd motion (depth of cut) was controlled by a large hand wheel connected to the shipper shaft via a chain. This almost startling feature meant that the second operator, positioned on the rotating boom, had to perform the dangerous task of controlling the shovel’s crowding action, in addition to opening the bucket at the right moment. No doubt he soon learned to keep his hands clear of the spinning wheel when the bucket encountered a sudden obstruction!

More than 200 Ruston No.20 steam shovels were built between 1913 and 1931. About 100 of them were sold to iron ore mining companies

Manufacture of Ruston-Dunbar excavators continued at a steady pace, receiving a boost from the Manchester Ship Canal construction, which began in 1888. By the time the canal was finished, 57 Ruston steam excavators had been purchased for the project. The canal was actually the first, recorded project to use large fleets of mechanised earth-moving equipment.

The 2¾-yard Ruston No.20 was the ‘standard’ steam shovel in the opencast iron ore mines of the English midlands. Here’s the last one working in 1964. (Pic: Lorne Hibbard)

As well as the Rustons, the project employed 19 fully-revolving excavators by Whitaker and Wilson, eight bucket chain excavators of French and German manufacture, 124 steam cranes including 18 Priestman grab excavators, 173 steam locomotives, 6,300 rail wagons and some 17,000 workers! An estimated 54 million cubic yards of earth and rock were moved over the six-year construction period. The contractor was TA Walker.

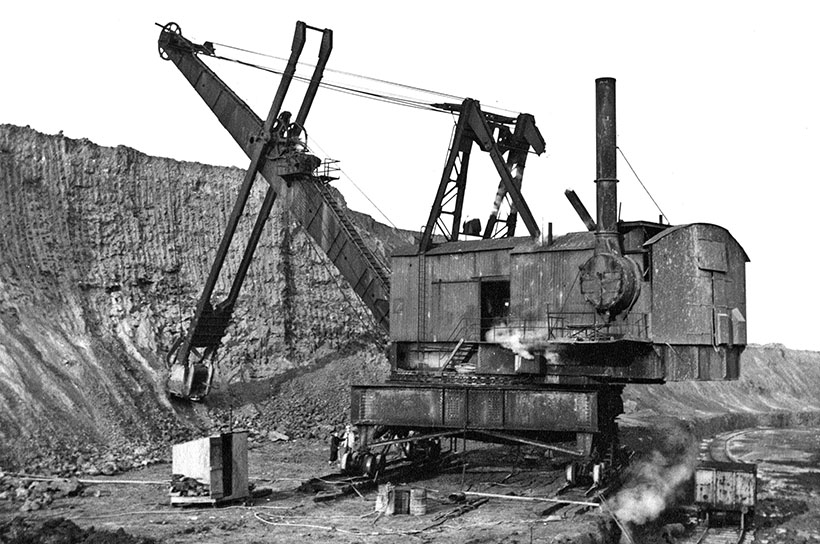

A few railroad shovels were built by Rustons. This No.30 was purchased by Kaye & Company for its cement quarry at Rugby.

In 1889, Ruston, Proctor & Co was employing 1,600 men, and its product range included steam rollers, traction engines and railway locomotives as well as excavators. That same year, Joseph Ruston decided it was time to go public, and became chairman of the new company, Ruston, Proctor & Co Ltd. Joseph Ruston died in 1897, but the family interest was carried on by his elder son, Joseph Seward Ruston.

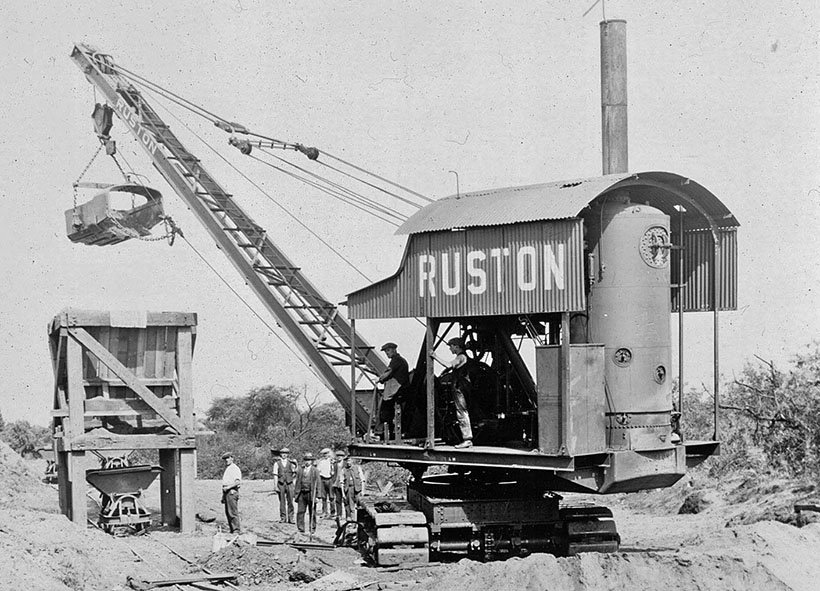

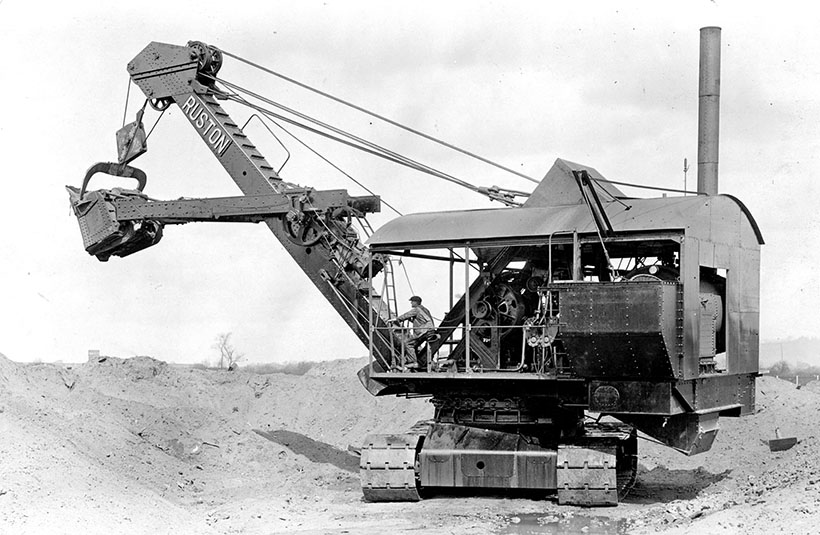

The Ruston No.10, introduced in 1921, was one of the first to be offered with crawler tracks as standard.

Full-circle shovel

Ruston’s first full-circle excavator was introduced in 1902, as the ‘12-ton Crane Navvy.’ As with the part-swing railroad shovels, tonnage classifications referred to lifting capacity, and not the overall weight of the machine. The mobility and dumping advantages of a digging machine able to rotate 360° were immediately recognised and, since a power crowd (thrusting) device was included, the machine could be operated by one driver, dispensing with the cranesman normally positioned on the boom.

Here’s another No.10, this time on test at the Lincoln works.

The steam-powered Ruston 12-ton machine was mounted on railway-type undercarriage, and fitted with a 2¼-cu/yd bucket. A direct-acting steam cylinder located on the lower part of the boom actuated the crowding device, which controlled the movement of the bucket arm by a rack and pinion system. This provided a stroke of only three feet but, on later, improved versions, the boom cylinder was replaced by a double-cylinder racking engine giving a stroke of six feet. Hoisting and swinging motions were controlled by separate, double-cylinder engines working through friction clutches.

The No.6 steamer joined Ruston’s roster in 1921.

NB: One of the Ruston 12-ton Crane Navvys survives to this day, at the Vintage Excavator Trust’s museum at Threlkeld, in the Lake District. Originally built in 1909 and restored to working order by Ray Hooley at Lincoln, the preserved machine first spent many years at the Museum of Lincolnshire Life in Lincoln, before being transported to Threlkeld.

The Ruston No.6 was the first ‘universal’ excavator, convertible to seven different front ends. Here it’s equipped with a backhoe attachment.

The success of the full-circle excavator didn’t, however, put an immediate end to sales of the part-swing Ruston-Dunbar excavator. Generally larger, and noted for its stability and reliability, this heavy-weight machine was still preferred by customers faced with tough construction or quarry operations. But, with improved design features and reliability in the field, sales of the full-circle Ruston 12-Ton Crane Navvy had surpassed those of the Ruston-Dunbar part-swing machine by 1908.

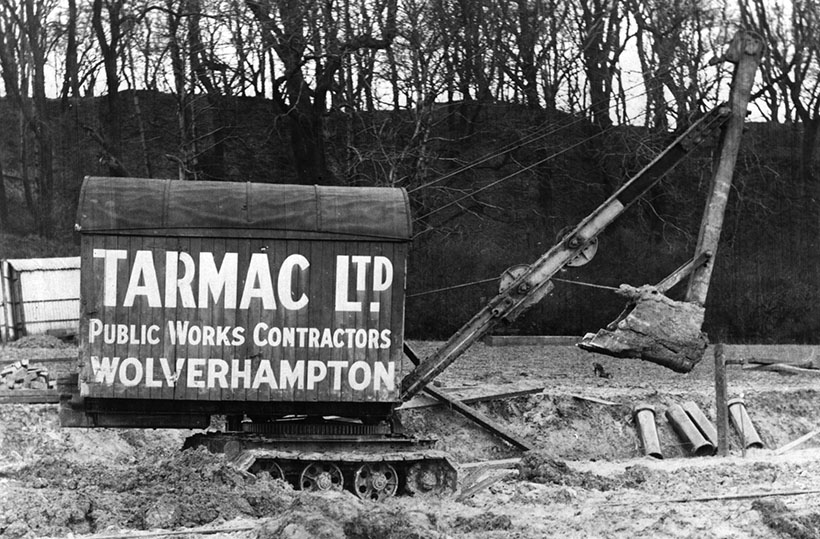

No doubt about who owns this No.4 excavator, that’s busy on a drain pipe job.

The last Ruston-Dunbar machine left the Lincoln factory in 1913. This date also marked the final delivery of the ‘Ruston Light Steam Shovel’; a smaller, part-swing railway-type shovel of ¾-yard capacity, introduced in 1907. The fact that only 12 of this model were recorded as sold, indicated that future markets of excavators in this size range would be for the fully-revolving types.

The No.4 was the most popular Ruston excavators, with 936 sold. This one’s working as a skimmer; one of seven available attachments.

Excavator range expanded

With the clear success of the Ruston 12-Ton fully-revolving excavator, several different sizes were added to the company’s roster over the next decade or so. First was the 8-Ton Crane Navvy introduced in 1909, with 1½-yard bucket and tipping the scales at 30 tons. Built on a similar design to the 12-Ton, more than 60 of this model were produced.

The ‘quarry and mine’ heavy-duty No.25 was introduced in 1928. Only eight were made, with the last three built as Ruston-Bucyrus machines after 1930.

Other models of various sizes were designed and built: 2½-yard 15-Ton in 1910, followed by the 16-Ton (1911), 18-Ton (1912), and 20-Ton (1913). At about the same time, the models began being referred to as model numbers instead of tons capacity, eg the 8-Ton became the No.8, 20-Ton became the No.20, etc. The 3½-yard No.30 followed in 1918, but only five of this model were built.

Showing the draw works of the steam-powered Ruston No.25.

If the Manchester Ship Canal gave the British excavator industry a boost in the latter part of the 19th century, the English ironstone opencast workings gave the industry its most important boost during the first part of the 20th century. Nearly all new developments of excavator design were directed towards this industry, and the many private companies involved were quick to experiment with – or purchase – different types of excavators. Ruston, Proctor & Co Ltd, and its successor, Ruston & Hornsby Ltd, took by far the lion’s share of this market. The latter company was formed in 1918 when Ruston, Proctor & Co. Ltd merged with Richard Hornsby & Sons of Grantham.

A Ruston No.75 steam dragline on test at the Lincoln works, demonstrating the flexibility of its four-crawler undercarriage.

The popular No.20

The steam-powered Ruston No.20 became the standard excavator in the ironstone surface mines. Just about every company purchased at least one, and some of the larger companies owned extensive fleets. The standard No.20 was mounted on rail wheels, weighed 62 tons and carried a bucket of 2¾ cubic yard capacity on a 26-foot boom. The very first machine was shipped to Sydney, Australia. The first in the UK was purchased by Midland Ironstone Company Ltd for work at Frodingham, Scunthorpe.

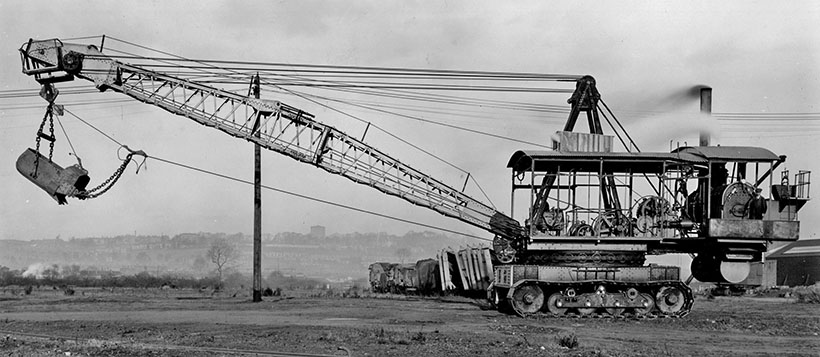

The Ruston No.75 was introduced in 1923, as a two-cubic-yard, purpose-built dragline.

Several different variations of the No.20 were offered, including stripping shovels with lattice or solid booms up to 55 feet long, and some with unusual front ends, such as a combined shovel and grab attachment. When crawler tracks became available, they were adopted as standard mounting for the No.20. Aided by the many combinations to meet varying working conditions, sales of the No.20 steam shovel totalled more than 200 during its 1913-1931 manufacturing period. Of these, about 100 worked in the English ironstone quarries.

The first Ruston No.135 striping shovel began work in 1925, at the Pitsford Ironstone mine. (Pic: Greg Evans Collection)

Unlike most long-established American shovel manufacturers, very few half-swing railroad-type shovels were built by Rustons; but they weren’t entirely forgotten. About 10 3½-yard No.30 Railroad Shovels were sold to British users between 1916 and 1923. Limestone quarry owners Kaye & Co at Rugby and Aberthaw & Roose at Aberthaw, were among the customers. A larger railroad shovel – the No.40 – was developed for a special order to work on the Takoradi Harbour project in the Gold Coast Colony, Africa. Three of these heavy-duty shovels with 3½-yard buckets, were delivered to the project between 1922 and 1923.

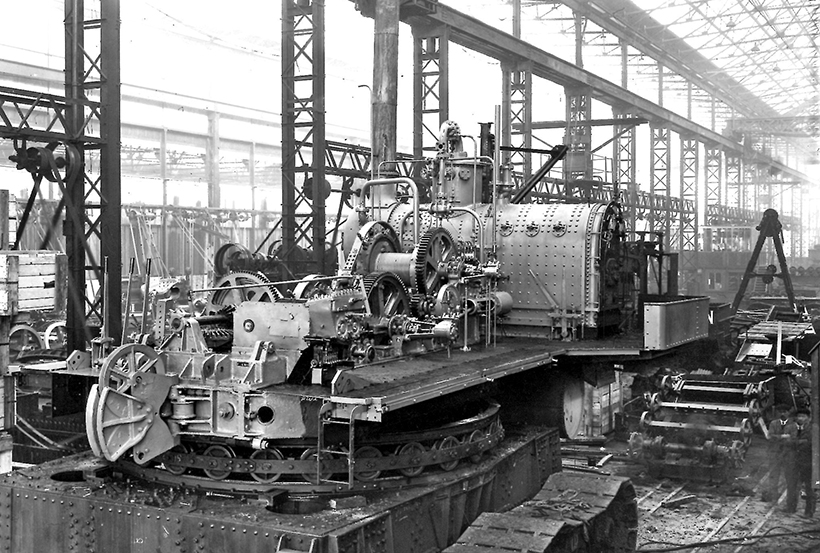

Assembly of a Ruston No. 135 steam crawler excavator at the Lincoln works.

In 1918, Ruston acquired the competitive business R Hornsby & Sons, based at Grantham, Lincolnshire, and the new company name became Ruston & Hornsby Ltd. The Hornsby company had built up a world reputation for quality products, and was famous for its pioneering work in developing the diesel engine. In 1896, it produced the world’s first oil-engined tractor then, in 1905, it built the Hornsby Chain Tractor, one of the earliest fully-tracked vehicles.

Both larger and smaller

The 1920s was a busy decade for Ruston & Hornsby, with the company’s range of excavators being expanded both upwards and downwards in size, encompassing all sizes from the smallest fully-revolving machines to the giant, stripping shovels; some of the world’s largest at that time.

The former No.8 steam shovel was re-designed as a more versatile machine, and introduced in 1921 as the No.10. Convertible to shovel, dragline or crane, it worked with buckets from 1¼ to 1¾ cubic yards, and was crawler-mounted in standard form. Power options were steam, oil-engine or electric. Also in 1921, the Ruston No.6 was launched with standard bucket of 7/8 cubic yard capacity.

This machine was regarded as the first truly ‘universal’ excavator, a common-base machine with a choice of power that was easily converted to shovel, dragline, backhoe, crane, grab, pile-driver or (later) skimmer. Both the No.6 and the No.10, together with the No.15 and No.20, would remain in Ruston & Hornsby’s product line until 1930. That year, the company’s excavator interests were merged with Bucyrus-Erie Company from America, to form the new jointly-owned operation, Ruston-Bucyrus Ltd.

Ruston No.300 steam stripping shovel – the largest in Europe – built in 1930 and owned by South Durham Steel & Iron Company. (Pic: Marshall Fayers Collection)

The small, ½-yard No.4 universal excavator, introduced in 1926, played a major role in changing the way excavation was done – from manual labour to mechanical machines. The No.4’s capability to convert easily to any of seven front ends, and with power choices including steam, electricity, petrol or diesel, guaranteed the model’s popularity.

It was such a good seller, in fact that, after the formation of Ruston-Bucyrus in 1930, the No.4 was the only excavator to continue in production from the former range of Ruston excavators. From 1926 to 1934, 936 No.4s were recorded sold, making it the most popular of all Ruston excavators.

Large stripping shovels

The 1920s decade was also marked by Ruston’s entry into the large stripping shovel market, for opencast mining. Some American machines of this type had already appeared in the English ironstone mines as early as 1916, so potential sales for stripping shovels larger than could be provided from a standard two-crawler excavator, appeared promising.

The first was the Ruston No.250, two of which were delivered in 1923. One of these steam giants wasn’t actually a shovel, but a dragline exported to the Sutlej Irrigation Scheme in India. It swung an eight-yard bucket on a 120-foot boom, and weighed some 300 tons. The second No.250 was a stripping shovel for Lloyds Ironstone Co, to work at Corby. It carried a bucket of six cubic yards on an 80-foot boom, providing a dumping radius of 94ft. 6in. By 1924, two more of the No.250 excavators had been shipped to India.

An even larger steam excavator followed in 1924, when the Ruston No.300 became available with an operating weight of 386 tons. Again, it appears the overseas market dominated shipments of these large machines. Of the 10 No.300s built up to 1930, only two worked in England. Of the others, six went to India, one to Nigeria and an electric version was sent to Australia to strip coal at the Morwell surface mines in Victoria.

The last steam shovel built was this Ruston-Bucyrus 52-B, that was delivered in 1935 to Alpha Cement Co. in Oxfordshire, photographed here by the author in 1969.

Of the two UK machines, one went to the London Brick Company in Bedfordshire, with a 10-yard bucket and a 90-foot boom, while the other was purchased by South Durham Steel & Iron Co. at Irchester, Northamptonshire. It had a 5½-yard bucket on a 95-foot boom.

An engineering masterpiece

The No.300 was a masterpiece of engineering and, with similar-sized machines built in America by Marion and Bucyrus, these stripping shovels were some of the largest, steam-powered machines to move on land. They ran on twin, parallel rail tracks with a four-wheel bogie mounted at each corner of the base. To prevent distortion of the base when moving, the two bogies on one side were connected to a beam pivoted at its centre to the main frame. This allowed the bogies to move vertically to compensate for track unevenness. The steam boiler was 20 feet long by 6ft 6in in diameter. The main hoisting engine had twin cylinders with 14x16in bore and stroke. The rotating engine was 11x10in bore and stroke.

The first of a smaller steam stripping shovel – the No.135 – was delivered to Pitsford Ironstone Co in 1925. Weighing about 60 tons, it was equipped with a 2½-yard bucket on a 75-foot boom, providing a maximum dumping radius of 85 feet. The No.135 was available as a dragline or shovel, and with a choice of rail or crawler mountings. A total of 10 No.135 excavators were shipped from the Lincoln factory, with three being steam-powered. The others were either straight electric or oil-electric powered by a Ruston vertical oil engine driving a 120kw generator.

The rail-mounted electric 250-ton No.135, with four-yard bucket, delivered in 1930 to the London Brick Co. at Bletchley, Bedfordshire, held the distinction of being the last excavator to bear the Ruston & Hornsby name. Two more were built to special order in 1934 and 1937 but, naturally, these carried the Ruston-Bucyrus name.

In 1923, two purpose-built steam draglines appeared; the No.60 carrying a 1½-yard bucket on an 80-foot boom, and the No.75 with bucket rated at two cubic yards on a 60-foot boom. Pivotal four-crawler mounting was standard on these machines, though early ones were rail-mounted.

The 52-B – the last steam shovel built – is seen here on demonstration at the Leicester Museum. (Pic: R Bracegirdle)

Another notable steam machine from the 1920s was the Ruston No.25, designed for heavy-duty quarry work. With a dipper of 3½ cubic yards, the shovel weighed 112 tons in service, and moved on a standard, two-crawler mounting. The first started work in 1928 for the Oxford & Shipton Cement Co. After this, four more No.25 shovels were shipped before 1930.

Then, as a result of the Bucyrus-Erie merger, this model was replaced by the 100-RB of the same capacity, but of American design. However, at this time there were part-built No.25 machines at the factory and orders to fill, so three more of this model were shipped carrying the Ruston-Bucyrus name. A No.25 shovel in working order can be seen at the Beamish Museum, near Durham.

When Bucyrus-Erie merged with Ruston & Hornsby in 1930, the steam excavator era was just about over. One lone steam-powered Ruston-Bucyrus 52-B shovel was ordered in 1935, and sent to the Alpha Cement Company Ltd’s quarry at Kidlington, Oxford. It was equipped with a 2¼ cu yd dipper and weighed 84 tons. In 1971, this last steam shovel built in the UK (and probably the world) was donated by its owners to the Abbey Pumping Station Museum, in Leicester, where it’s been restored to working condition.

For a money-saving subscription to Old Glory magazine, simply click here

Portions of information for this article were gathered from publications including: Excavating machinery by William Barnes (1928), Excavating machinery in the Ironstone Fields by William Barnes (1942), and Lincoln’s excavators – the Ruston years 1875-1930 by Peter Robinson (2003). The latter is one of four volumes containing detailed histories of Ruston and R-B machines, and is highly recommended.