The sinking of the German battlecrusier, Scharnhorst

Posted by Chris Graham on 5th June 2023

Conrad Waters recounts the sinking of the German battlecrusier Scharnhorst in the final action between capital ships in European waters.

The German battlecruiser Scharnhorst in late 1939. By this time she had been fitted with a lengthened ‘Atlantic bow’ that improved her sea-keeping abilities. (Pic: US Naval History & Heritage Command NH101559)

The early afternoon of Christmas Day, 1943, saw seasonal festivities well under way aboard the German battlecruiser Scharnhorst. The ship was secure in the Altafjord, in Northern Norway, and her crew was making the most of a festive relaxation in normal routines. Some had even been ashore skiing that morning. But the relaxed mood was abruptly interrupted when the unwelcome order to prepare for sea was relayed through the loudspeakers. Christmas decorations on the mess decks were quickly tidied away as Scharnhorst was readied for imminent departure.

The unforeseen urgency had been driven by the sighting of a British convoy of merchant ships bound for the Soviet Union. The life-and-death struggle in the east was going badly for Germany, making the prospect of disrupting the flow of allied supplies an attractive one. Recent convoys on the Arctic run had completed their voyages unscathed, adding pressure on Germany’s Kriegsmarine to make a decisive intervention. A plan – Operation Ostfront – had been drawn up to intercept the vital supply route.

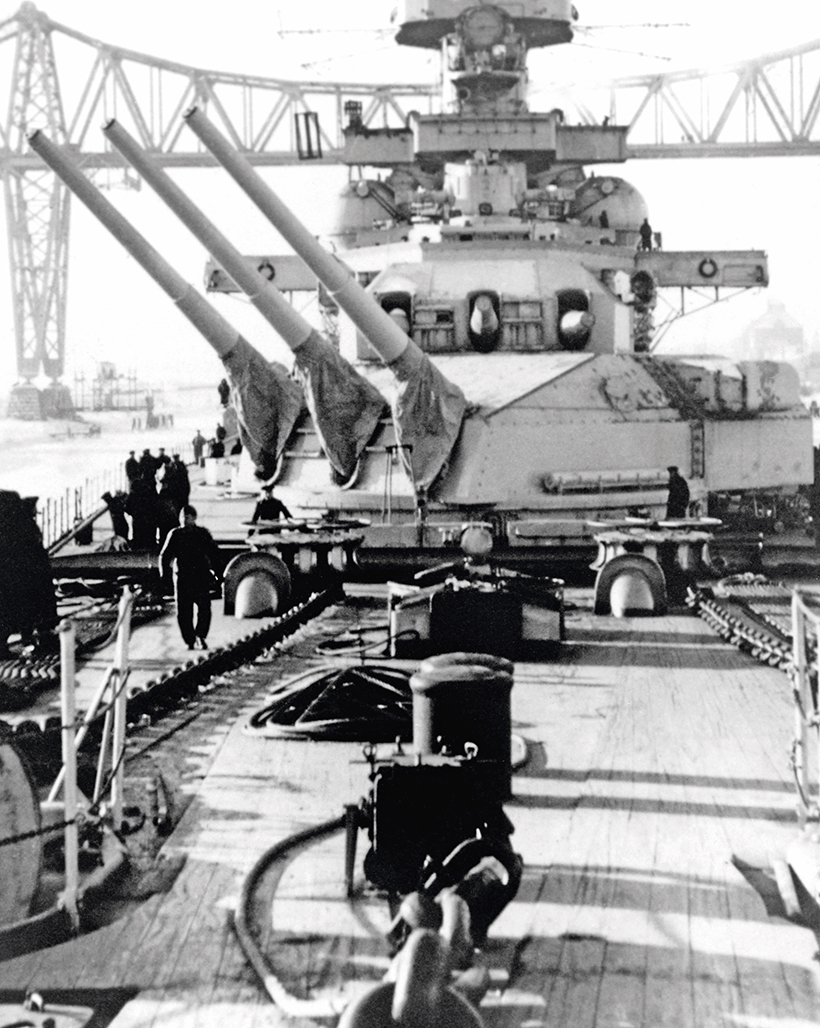

Scharnhorst’s triple 11-inch ‘Anton’ and ‘Bruno’ turrets. The battlecruiser’s main armament was relatively weak compared to that of other capital ships. (Pic: US Naval History & Heritage Command NH 101571)

That evening, with Konteradmiral Erich Bey and his staff embarked, Scharnhorst weighed anchor and proceeded out of the Altafjord into winds that were approaching gale force. Accompanied by five large destroyers, the battlecruiser was regarded as having a fair prospect of success against the Royal Navy cruisers and lighter forces that had been identified as the convoy’s immediate escort. Less certain was the nature of any additional opposition the German ship might face.

With the weather hindering effective reconnaissance, little was known about the whereabouts of the Royal Navy’s capital ships, which were known to provide distant cover to the Arctic convoys. This was to prove a justified concern. In the course of the next 24 hours, the German ship would be brought into action by the battleship Duke of York and, of Scharnhorst’s complement of about 2,000, only 36 survived the engagement.

Scharnhorst had enjoyed a brief but distinguished career. The lead ship of a pair of new capital ships ordered during Germany’s rearmament in the run up to World War II, she was built at the Kriegsmarinewerft at Wilhelmshaven and commissioned in January 1939. Along with her sister, Gneisenau, she formed the heart of the Kriegsmarine when hostilities erupted.

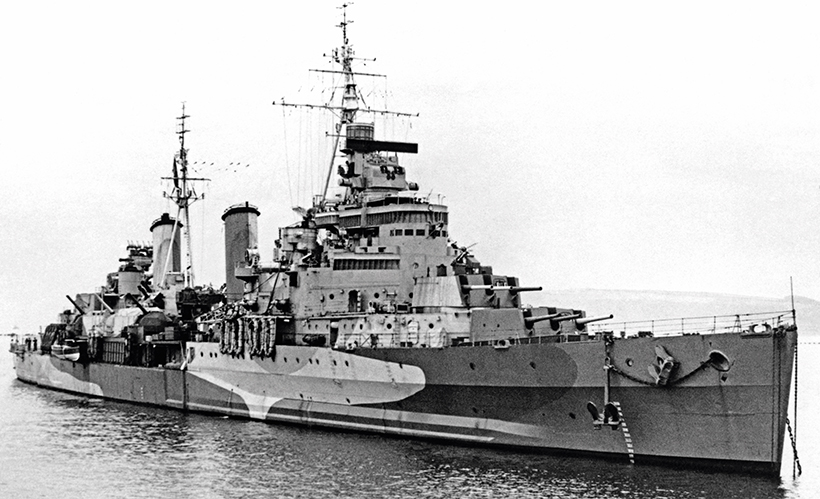

The ‘County’ class cruiser Norfolk secured two important early hits on Scharnhorst, putting her forward radar set out of action. This photograph dates from June 1943. (Pic: Admiralty)

Displacing around 35,000 tons in standard condition, Scharnhorst was similar in size to many contemporary battleships, and was initially designed to counter France’s Dunkerque class ships. However, an important limitation was her relatively weak main armament, consisting of nine 28cm SK/C34 guns in three triple turrets. This was partly a legacy of previous treaty restrictions. Her hull design showed poor seakeeping abilities on entering service, but this was largely resolved by modification with a raised and lengthened ‘Atlantic bow’ before the end of 1939.

Scharnhorst played a prominent part in the early years of the war, typically operating in company with Gneisenau. The two battlecruisers sank the armed merchant cruiser Rawalpindi in November 1939. An inconclusive engagement with the Royal Navy’s Renown at the start of the Norwegian invasion in April 1940 was followed by the destruction of the carrier Glorious and her two escorting destroyers at the end of the campaign. Scharnhorst did not emerge unscathed from this action, however, suffering a damaging torpedo hit from Acasta that put her in dockyard hands for much of the rest of the year.

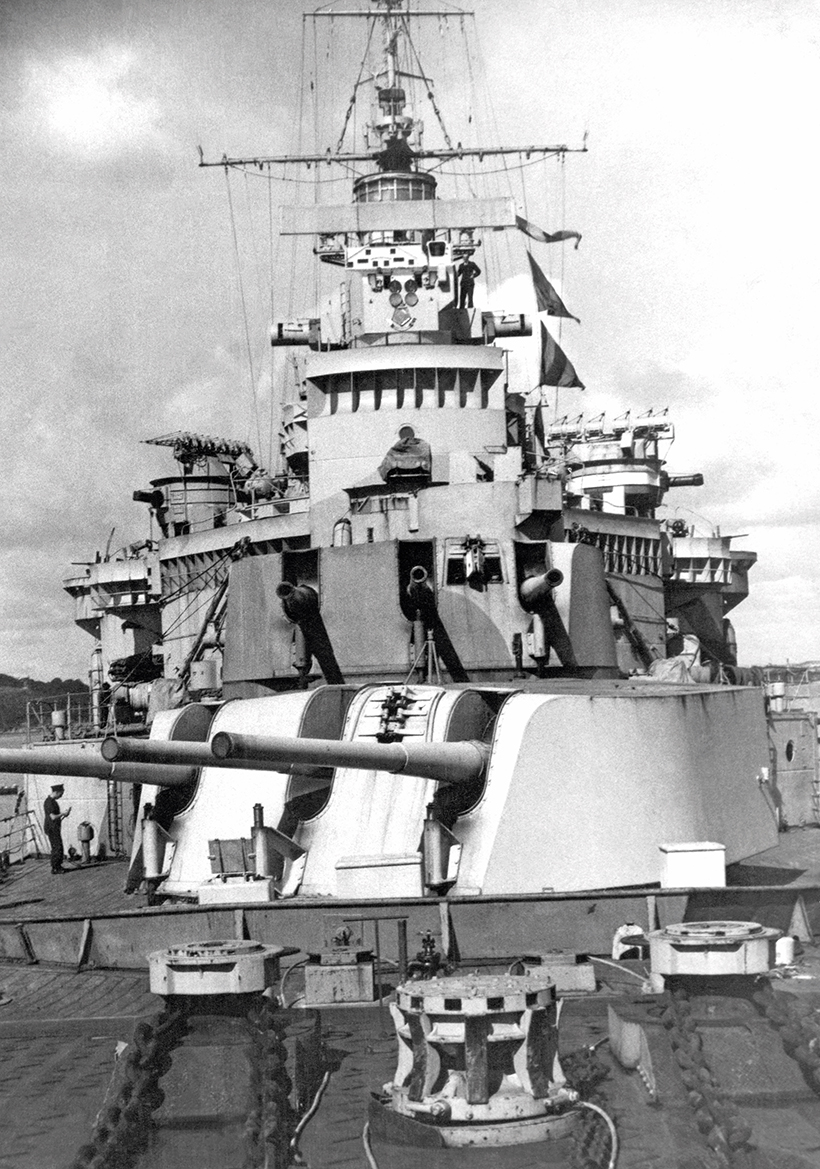

This forward view of Sheffield’s six-inch guns was taken at Devonport in 1943. Sheffield was part of Vice-Admiral Robert-Burnett’s cruiser force at the battle. (Pic: Author’s Collection)

In 1941 the two German battlecruisers were dispatched to raid the Atlantic supply lanes but suffered increasingly from bombing attacks on their French bases. This prompted their return to Germany in the famous ‘Channel Dash’ of February 1942. Subsequent bomb damage to Gneisenau meant the two sisters were never to operate together and, in early 1943, Scharnhorst deployed to Norway to reinforce operations against the Arctic convoys. Here, her service was largely uneventful before the Battle of the North Cape, and was largely confined to a raid against the Norwegian garrison at Spitzbergen, in September 1943.

A trap is set

In spite of the relative lack of German surface activity in the Arctic theatre, the British Admiralty assessed that the resumption of supply convoys to Russia during the autumn of 1943 would likely elicit a response. Heavily assisted by ‘Ultra’ intelligence, they hoped to turn the expected German naval operation against the supply route to their own advantage.

After previous convoys had escaped attack, it seemed likely that the late December convoy – code-named JW55B – would be a prime target for interception. The Royal Navy was already waiting when Scharnhorst began her sortie.

The British plans for defending the convoy were focused on two separate naval forces. Force 1, travelling westwards from Russia, comprised the cruisers Belfast, Norfolk and Sheffield. Its role was to support the returning empty convoy RA55A before closing with JW55B at the point of maximum danger.

The cruiser Belfast served as flagship of Vice-Admiral Robert Burnett, the commander of Force 1 during the Battle of the North Cape. (Pic: Admiralty)

Force 2, commanded by Home Fleet C-in-C Admiral Sir Bruce Fraser, comprised the battleship King George V, the cruiser Jamaica and four destroyers. It was to head east from Iceland so as to be in the optimum position to ambush Scharnhorst between the convoy and its Norwegian base.

The cruisers engage

The battle commenced at 0840 in the morning of Boxing Day, December 26th, 1943, when Belfast, flagship of Force 1, picked up Scharnhorst on radar at a range of about 20 miles to the northwest. The German ship was searching unsuccessfully for the convoy and had already detached its accompanying destroyers to extend the searchline. They were to play no part in the action that followed, ultimately returning safely to Norway.

The cruiser Jamaica is widely credited with firing the spread of torpedoes that finally sent Scharnhorst to the bottom. This photo was taken at Scapa Flow, in 1944. (Pic: Admiralty)

The range dropped rapidly as Force 1 closed in on Scharnhorst, with Belfast opening fire with starshells at 0924, with the range about 10,000 yards. Only Norfolk fired with effect in the brief engagement that followed, landing at least two eight-inch hits on the German ship. One of these destroyed Scharnhorst’s forward radar set, leaving the battlecruiser partly blind in the prevailing Arctic conditions. It provided the British with a decisive advantage.

Scharnhorst quickly broke off this initial engagement, using her superior speed to open the distance from the Royal Navy cruisers and break radar contact. However, the lure of the convoy proved too much of a temptation and Belfast again picked up the German ship at 1205.

By this time, Force 1 had been reinforced by four destroyers from JW55B’s close escort, considerably strengthening its capabilities. Nevertheless, this time Scharnhorst got the better of the engagement, hitting Norfolk with two 11-inch shells. These put her ‘X’ turret out of action and disabled all but one of the radar sets, as well as starting a fire that took several hours to extinguish.

The battleship Duke of York at sea in 1942. She acted as flagship of the Commander-in-Chief of the Home Fleet, Admiral Sir Bruce Fraser, during the Battle of the North Cape. (Pic: Admiralty)

Despite this success, Scharnhorst now gave up on the plan to attack the convoy. Instead, she retired southwards, shadowed at distance by the British cruisers. These kept Duke of York and the other ships of Force 2 regularly informed of the German battlecruiser’s movements, allowing it to maintain an interception course.

Enter Duke of York

Shortly after 1615, Duke of York’s surface warning radar picked up Scharnhorst at a range of 25 miles, identifying Belfast shadowing at a distance astern shortly after. The range closed rapidly and, just before 1650, the two Royal Navy ships illuminated the battlecruiser with starshells. Appearing of enormous length and of silver-grey colour to British observers, Scharnhorst – with her main armament trained fore and aft – had seemingly been taken completely unawares by the arrival of the British capital ship. Both Duke of York and Jamaica opened fire at around 12,000 yards range.

There followed a long eastwards chase. Duke of York scored hits with her early salvos, most notably disabling Scharnhorst’s ‘A’ or ‘Anton’ turret, and forcing the partial flooding of ‘B’ (‘Bruno’) magazine. However, the German ship’s speed was undiminished and the range between the opposing forces steadily opened. An atmosphere of frustration and disappointment enveloped the British ships as it seemed increasingly likely that Scharnhorst would get away.

The destroyer Musketeer, pictured here in 1942, was one of a number of ships involved in the final melee that resulted in Scharnhorst’s destruction. (Pic: Admiralty)

Despite these concerns, Duke of York’s radar-directed fire had proved remarkably accurate and a series of damaging hits had been scored. One, which hit just as the British battleship checked fire around 1820 due to the ever-increasing range, detonated in Scharnhorst’s No.1 boiler room, temporarily reducing her speed to just 10 knots. This allowed the accompanying British destroyers to launch a series of torpedo attacks.

A number of these weapons found their mark, permanently crippling the German ship. However, the fighting was not all one-way. The destroyer Saumarez suffered considerably from the attentions of Scharnhorst’s secondary armament, losing 11 of her crew to splinters after a shell passed through her director.

A rare photo of Duke of York taken shortly after the Battle of the North Cape. The engagement effectively marked the end of the battleship era in European waters. (Pic: Author’s Collection)

Scharnhorst was, however, now clearly doomed and the British ships closed in for the kill. The battlecruiser was pummelled by gunfire and subjected to a series of further torpedo attacks from the cruisers and destroyers as her speed slowed to a crawl.

It is widely believed that it was two hits from a triple spread fired from Jamaica’s starboard tubes at 3,750 yards at around 1940 that finally sent Scharnhorst to her doom. However, a number of ships launched torpedoes at this time, so it’s difficult to be sure about which ship landed the fatal blow.

A brave ending

Obscured by smoke, Scharnhorst finally slipped beneath the waves around 1945 on the evening of December 26th. While many of her crew managed to escape the vessel, their chances of survival in the Arctic waters were slim and few survived, none being more senior than an acting petty officer. By contrast, British casualties and materiel harm had been slight, and the damage to Duke of York was only superficial and limited to her masts.

The destroyer Saumarez – seen here on completion in 1943 – suffered 11 fatalities in the course of the action against Scharnhorst. She later played a leading role in the destruction of the Japanese heavy cruiser Haguro in the Battle of the Malacca Strait. (Pic: Admiralty)

Scharnhorst had fought a brave last battle against unbeatable odds. In addition to the Royal Navy’s numerical superiority, the British ships’ technological prowess – particularly in the field of radar – had provided a significant advantage. The Battle of the North Cape also marked the end of an era. Never again would battleships face-off against each other in European seas.

Scharnhorst |

| Namesake Gerhard Johann von Scharnhorst (1755–1813) |

| Builder Kriegsmarinewerft, Wilhelmshaven |

| Laid down 15.6.1935, launched 3.10.1936, commissioned 7.1.1939 |

| Displacement circa 35,000 tons standard displacement |

| Dimensions 234.9 m x 30m, draught 9.9m |

| Power circa 160,000shp, three Brown, Boveri & Co geared steam turbines |

| Speed 31 knots |

| Complement circa 1,900 plus supernumeraries and flag staff at the time of the Battle of North Cape |

The feature comes from the latest issue of Ships Monthly, and you can get a money-saving subscription to this magazine simply by clicking HERE