White Star Line’s Olympic, Titanic and Britannic liners investigated

Posted by Chris Graham on 8th February 2023

Simon Mills delves into the fascinating history of the White Star Line’s fabled Olympic-class ships Olympic, Titanic and Britannic.

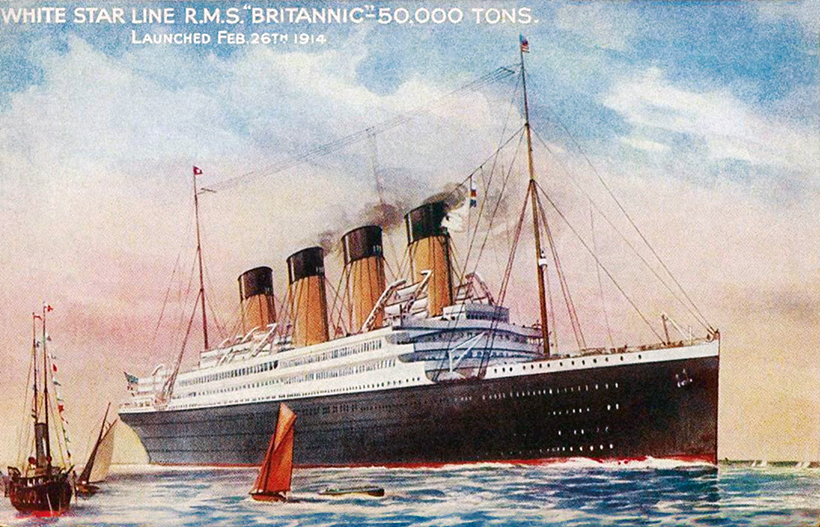

A White Star Line publicity postcard for Britannic, based on the 1914 oil painting by Charles Dixon. (Pic: Simon Mills Collection)

White Star’s most famous ships haven’t always been as much a part of the public consciousness as they are today. In fact, it’s curious to think that, in light of the considerable interest in Titanic, until the 1950s the story of the ship had been largely forgotten. It was only the release of Twentieth Century-Fox’s film Titanic in 1953, starring Clifton Webb and Barbara Stanwyck, combined with the publication of Walter Lord’s A Night to Remember three years later, that the story of the legendary White Star liner fired the public’s imagination.

This 40-year lapse may explain how some of the facts associated with Titanic have been related through numerous fables, legends and myths. Much of what we read on the Titanic is often ‘apocryphal, or at least wildly inaccurate’, but, while the more dedicated Titanic buffs can see through the historical haze, for ship enthusiasts with less of a fixation on the White Star behemoths, or even the general public who may even see the story of Titanic as more of an event, rather than a ship, it probably comes as no surprise to see them taken in by the attractive myths surrounding the ship.

Leaving aside the Olympic/Titanic switch conspiracy theories, the legends actually start at the beginning of the story, with the notion that the White Star Line had always proposed a trio of ships to compete with Cunard’s Lusitania and Mauretania. The reality, however, is that the historical documentation shows this not to be the case.

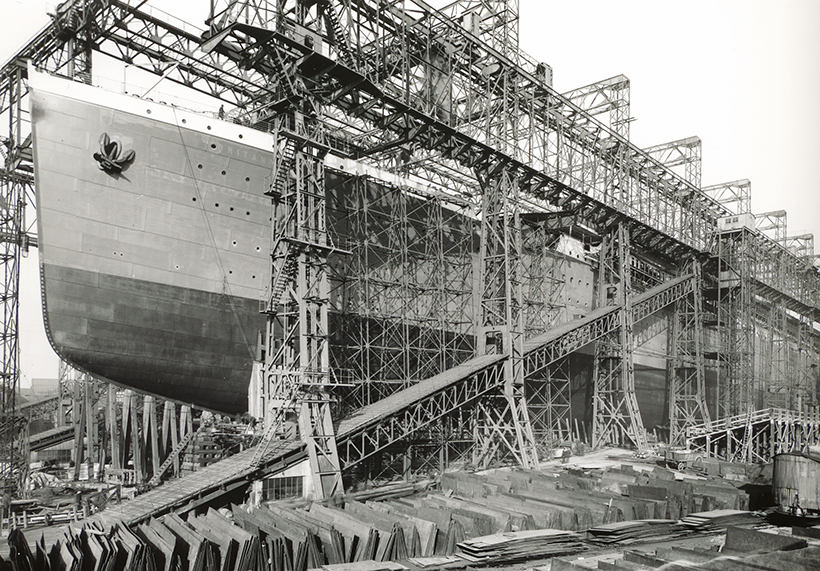

Britannic ready for launching on slip No.2 at the Harland & Wolff shipyard in Belfast. (Pic: Harland & Wolff)

When the two Cunard sisters entered service in the autumn of 1907, White Star had nothing remotely comparable in terms of size and speed. As a result, the company had little option but to respond in kind. However, while Harland & Wolff’s approved design for the Olympic class (Design ‘D’) was signed off on 31 July 1908, the initial order extended to only two vessels: Olympic and Titanic.

With these two ships, White Star Line would once again be in a position to compete with Cunard, operating the largest and most luxurious ships on the North Atlantic, if not necessarily the fastest. The reality is that Cunard liked what they saw in the Olympic class design so much that, barely two months after Olympic’s launch, the contract for Aquitania had been awarded to John Brown & Co. With the German Hamburg Amerika Line planning an even larger trio, White Star had to proceed with the construction of its third Olympic-class vessel in order to remain competitive.

The order to proceed with a third vessel was confirmed in June 1911, before Olympic had even made her maiden arrival at New York, which straight away brings us to the legend that yard no.433 was originally intended to be named Gigantic, in order to complement the nomenclature of her two older siblings. It is an attractive idea, but in fact none of the engineering records at Belfast show any evidence of the vessel’s name being revised due to any perceived embarrassment following Titanic’s sinking. In fact, 433 was always intended to be named Britannic.

Britannic, in her role as a hospital ship, takes on wounded at Mudros. She was operated as a hospital ship from 1915 until her sinking near the Greek island of Kea, in the Aegean Sea, in November 1916. (Colourisation by Andrey Alekseev)

Nor was Britannic enlarged as a direct result of the double skin incorporated into the design following the Titanic disaster. A double skin had been retrofitted into Olympic during the winter of 1912-13, supposedly to render the ship impervious to the damage that overwhelmed Titanic, so it seemed logical to assume that the same modification in Britannic, which was only framed to the height of the double bottom by the time Titanic sank, would account for the additional 18 inches in her beam.

However, the records at Belfast indicate that the increased beam had been approved months before Titanic even left Belfast. Olympic’s reconstruction had not simply addressed the addition of a double skin and higher watertight bulkheads, but it also resulted in a much stiffer hull, necessitated by a number of flexing and structural issues which had become apparent during the ship’s early commercial operation. The additional beam also gave Britannic better structural integrity.

All of which brings us neatly to the issues of alleged design flaws and the use of poor-quality materials. Allegations of brittle steel and low-quality wrought iron rivets are not new, but is there really much evidence to suggest that Titanic was lost due to poor workmanship? It would be pointless to claim that there were never any structural issues; after all, by the early 20th century there had never been a vessel even closely approaching the size of Olympic and Titanic.

Olympic in the floating dock at Southampton, in September 1924. The dock was built by Armstrong Whitworth, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, and was capable of lifting 60,000 tons. The completed dock was moved to Southampton in April 1924, and was the largest floating dry dock in the world when it was officially opened by HRH Prince of Wales on 27th June, 1924. (Pic: Getty Images)

Harland & Wolff was always working with many unknown factors when addressing the more serious structural issues in Olympic in her later years, and conceded that the building of such large ships had always been ‘experimental’. The Board of Trade later acknowledged that some of the more serious defects in the design ‘ought to have been foreseen’.

Perhaps the best evidence of the quality of Harland & Wolff’s turn-of-the-century workmanship can be seen today in the wreck of Britannic. For over a century the ship has lain on her starboard side in 390ft of water at the bottom of the Kea Channel, yet, despite the superstructure being largely unsupported, practically everything remains in situ.

More impressive is the sight of the giant 100-ton boilers preserved in near-pristine forward boiler rooms, and the towering 40ft reciprocating engines, each weighing many hundreds of tons and yet still attached to the tank top in spite of their almost horizontal angle. Everything that has been seen, both on and inside the wreck, indicates nothing but the finest workmanship.

In the open sea, Titanic heads for New York via Cherbourg and Queenstown. (Pic: Vasilije Ristovic)

Even in death, Britannic has been unable to escape the legends surrounding Titanic and, in many ways, she has become the victim of other equally scurrilous conspiracy theories. Wartime allegations of the ship being used to carry illicit contraband and troops during World War I – a serious violation of her protected status as a hospital ship – have also not helped.

Perhaps it is understandable in a time of war, when truth is questionable on most sides, that even the merest sniff of a scandal resulted in additional claims of the wreck being deliberately misplaced by the Admiralty in order to help conceal their terrible secret.

Once again, the official records provide facts which are somewhat less controversial. Far from confirming that the wreck had been deliberately misplaced, Britannic’s log – an open document since the 1960s – clearly records that the ship sank in the area reasonably close to where Jacques Cousteau eventually found her in November 1975.

Olympic’s maiden arrival at Pier 59 in New York. The scarred paintwork on her bow is a testament to the superior speed of White Star’s new flagship. (Pic: US National Archives)

As to the allegation that the wreck had been deliberately misplaced, admittedly the symbol on the old charts was a good 6.75 nautical miles from the location given by Cousteau, but the question arises as to why it was ever linked to Britannic in the first place? Subsequent investigation of the Kea Channel has revealed no fewer than three other unmarked wrecks, two from World War I and another from World War II, with HMS Louvain, sunk in January 1918, closest to the charted position.

The recent discovery of the fourth vessel completes the list of the four known wrecks in the Kea Channel, namely Burdigala, Britannic, HMS Louvain and Città di Tripoli, yet somehow the position was only ever associated with Britannic.

Nor have the Germans been able to evade the intense scrutiny of the conspiracy theorists, with allegations that Britannic, a hospital ship, was deliberately torpedoed, even though the records clearly indicated the ship was victim of a mine laid by the U73. The mine evidence was confirmed in September 2003, when fragments of the mine barrier were located with sonar and later photographed.

An early advertising poster for the Olympic class, before many of the details had been fine tuned. (Pic: Getty Images)

The legends surrounding Titanic and her sisters have always been attractive, but it is only through a closer look at the Olympic class as a whole that it is really possible to put the story of Titanic into its full context, while at the same time laying to rest some of the myths. In a way it is sad to be thinking along these lines at all.

The incredible story of Titanic needs no embellishment – it never has done – but while some may mourn the loss of the more fantastic elements of the story, the story of the Olympic class as a whole will always continue to fascinate future generations. And who would want to change that?

For the full story of White Star Line’s famous trio, see the author’s book ‘Olympic Titanic Britannic: The Anatomy and Evolution of the Olympic Class’.

Olympic having returned to her berth at Southampton after the mutiny of April 1912. (Pic: Getty Images)

This feature comes from the latest issue of Ships Monthly, and you can take advantage of a money-saving subscription to this monthly magazine simply by clicking HERE

Previous Post

Gradall Hydraulic Excavator; a world first!

Next Post

Ultra-rare 1984 Simca van – the last UK survivor!