A much-cherished 1938 Ferguson Brown still going strong!

Posted by Chris Graham on 22nd January 2024

Willie Carson enjoys the chance to discover more about James Adams’ beautifully original and much-cherished Ferguson Brown.

Ferguson Brown: Having been on the same farm for 86 years, this tractor has seen the change from horse-drawn implements to three-point linkage equipment.

Harry Ferguson was fed up with working the land on his Co Down farm with horses. “There had to be a better way,” the young man reasoned. It took a while but, eventually, he designed a tractor which would change world agriculture forever, and that machine was the Ferguson Type A; better known as the Ferguson Brown.

Ferguson began a close association with the tractors of the Edwardian era when he was asked to demonstrate and promote the introduction of agricultural mechanisation to increase the nation’s wartime food production. With this experience in the field, his developing mechanical genius and his skilled salesmanship, it was little surprise that he took an agency for the Overtime tractor from America.

A real drag!

Soon it became evident to Ferguson that the tractors of the time were handicapped by the physics of simply dragging a plough through the ground with a chain. While doing this, tractors relied on their own weight to provide sufficient traction, most of which had to be concentrated over the rear wheels to ensure adequate grip. But Ferguson appreciated that this design approach was inherently flawed, due to the weight needed over the front axle, which was essential to prevent the tractor from rearing up should a hidden obstacle be struck by the implement. To eliminate these compromises, a new approach was required.

The tractor was demonstrated without mudguards. They were included in the purchase price and delivered at a later date. Strangely, they were never actually fitted and remain in James’ possession.

While the arrival of the Fordson Standard improved the power-to-weight ratio, Ferguson was working on a more unified approach to the combination of tractor and implement. His early Eros plough was followed by the Duplex hitch design, and then, in 1925, he applied for a patent for his system of draft control. The initial designs were based on two top links and one lower link, but these were soon reversed to create the more familiar arrangement we’re all familiar with today.

Ferguson and his engineers first designed an arrangement with lower link sensing, but this led to complications that were to be solved when the top link did the sensing, and the lower ones did the lifting and lowering. With that arrangement established, all they then required was a tractor that could incorporate the new designs. In 1932, Ferguson began to draw up plans for a new machine, and this process resulted in the prototype ‘Black Tractor’, from which the Ferguson Brown – appearing in 1936 – was derived. It had only taken 19 years!

Family farming

James Adams has farmed in Co Down since his youth. “My father, also called James, farmed 130 acres here in partnership with his brother,” he told me. “They grew cereals, vegetables and early potatoes, with the vegetables going to market in the centre of Belfast, about 14 miles away. They needed five horses to keep the farm running, and that, of course, meant that they had to set aside quite a lot of land for grazing, to make hay and to grow oats just to keep the horses fed.

‘Design is the art of making complex things simple’, according to Sir Alec Issigonis, the creator of the Morris Minor and the Mini. Harry Ferguson had already worked out how to put this maxim into practice.

“When my father left school at 14 years old, his father would send him into the market with produce loaded onto a horse’s cart, and this remained the way things were done until 1926 when he bought his first lorry – a Ford Model T which could carry a one-ton load. In 1936, he bought a Model A lorry, which was classed as a 30cwt (1.5-ton) lorry, but that one regularly carried two tons, so there were a few blown tyres over the years!

“After the war, he bought an ex-army fire engine; a Ford with a V8 engine that ran so sweet that you could hardly hear it! He removed the pump (which was powered by another Ford V8) and built a load body on the back. He drove that vehicle until the engine was done, at which point he swapped it with the V8 engine that had been used to drive the fire engine’s water pump. That kept the lorry going for a few more years,” James explained. He then apologised to me for taking the conversation away from the subject of his Ferguson Brown, oblivious to the fact that his recollections were providing such an interesting glimpse into the world of farming in the 1920s and ‘30s.

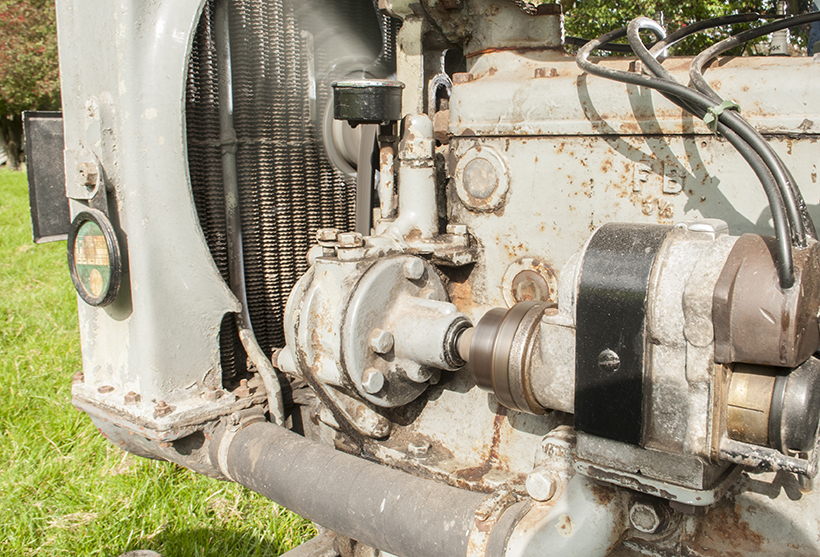

The early style of radiator construction and the magneto are typical of the engineering of the period. Despite its age, James’ Ferguson Brown engine bursts into life willingly.

Time for a change

“Anyway, going back to 1938,” he continued, “my father had become fed up with working the land with horses so, in March that year, and after completing his business at the market, he walked down May Street towards Harry Ferguson’s showroom, to take a closer look at the new Ferguson Brown tractors on display there. According to family folklore, at 11 o’clock the next morning, a demonstration driver from the dealership arrived in an Austin 16, towing a trailer that was carrying a tractor and plough. What’s more, Harry Ferguson himself followed in his own car!

“The demonstrator driver operated the tractor at a steady pace, but before long, Ferguson stepped in and said that he would take over and show what the tractor could really do, and proceeded to plough a few more rounds with a bit more speed. My father knew that the bottom corner of the field was wet and had warned Ferguson about that. He suggested that, as there was no other tractor available on the farm to pull him out, he should keep to the drier part of the field. But Ferguson carried on regardless, until the tractor came to a halt.”

James doesn’t know how the Ferguson Brown was extricated from its sticky position, but since there were five Clydesdale horses in the yard, a fertile imagination might jump to its own conclusions! The issue was compounded by the fact that, on these early Fergusons, the hydraulic pump was driven off the transmission, and so required the wheels to be turning before the lift arms could be raised. Might this have been the day when Harry Ferguson decided that the hydraulics should operate independently of the rear wheels? We’ll never know.

A traditional outing in a very traditional setting! James regularly takes BZ 5710 to the Ferguson Working Day at the Ulster Folk Museum in Cultra, Northern Ireland.

“Anyway, my father bought the tractor that day. I still have the farm account books from the period, which show that the tractor cost £225, the plough was £25 and there was a delivery charge of £2. There’s another entry from a few weeks later, which shows that £50 was paid for a grubber and a drill plough for the potato ridges. The note of the £2 delivery charge reminds me of a neighbour who bought a new Fordson Standard at about that time.”

Wheels and lugs

“He was known to be careful with his money and, given that £2 was probably more than a working man’s weekly wage, had decided to drive the tractor home from the other side of Belfast himself. The tractor was ordered with steel wheels and spade lugs, so the lugs were removed for driving on the road and stored in a hessian bag on the footplate.

However, the rough ride over the stone set cobbles soon wore a hole in the bottom of the bag, and the spade lugs began to fall out onto the street. Fortunately, the neighbour had a friend who was a lorry driver in the city, and he spotted the trail of steel lugs and, knowing about the recent purchase of the Fordson, picked them up as he went and returned them all to a grateful farmer that evening!

The evenly-spaced spark plugs indicate that this is the later, in-house, David Brown engine. The earlier Coventry Climax engine had its plugs arranged in offset pairs.

“Some of the horse implements were converted for use behind the Ferguson Brown, including the Albion binder, the McCormick reaper finger bar mower and the hay tedder; all of these were ground-driven, but some equipment was made specially for the tractor, like the hand-tipping trailer and the flat roller. The horse roller was two barrels wide, but there was one made with three barrels to make better use of the tractor’s extra power.

“The first memories from my childhood days are of my father opening drills for the potatoes with the tractor. The potato seeds were all planted by hand, and then the drills were closed with the Ferguson ridger. This was all very precise work, but the tractor’s steel front wheels gave good, accurate steering.”

The Ferguson Brown crankshaft runs in white metal bearings, so James has fitted a Smiths oil pressure gauge for his own peace of mind.

Tyre swap

During the war, tyres for agriculture were in short supply, but eventually, a rear set was acquired for the Ferguson Brown, although they didn’t stay on the tractor for long, as James explained. “In 1942, my father bought a Fordson N on steel wheels with spade lugs. Since it was quicker on the road – and it ran on TVO, which was cheaper than petrol, plus there was a shortage of tyres – he took the tyres off the Fergie Brown and put them onto the Fordson for the remainder of the war.

“Later, he was able to buy secondhand tyres for the Ferguson’s rear wheels, but she had steel wheels on the front for many years. In fact, they remained on the tractor for so long that the front wheel, which runs in the furrow while ploughing, wore right through and simply collapsed one day. Fortunately, the local blacksmith was able to put the wheel back together again, after which it lasted for many more years. In fact, I still have it in the shed today!”

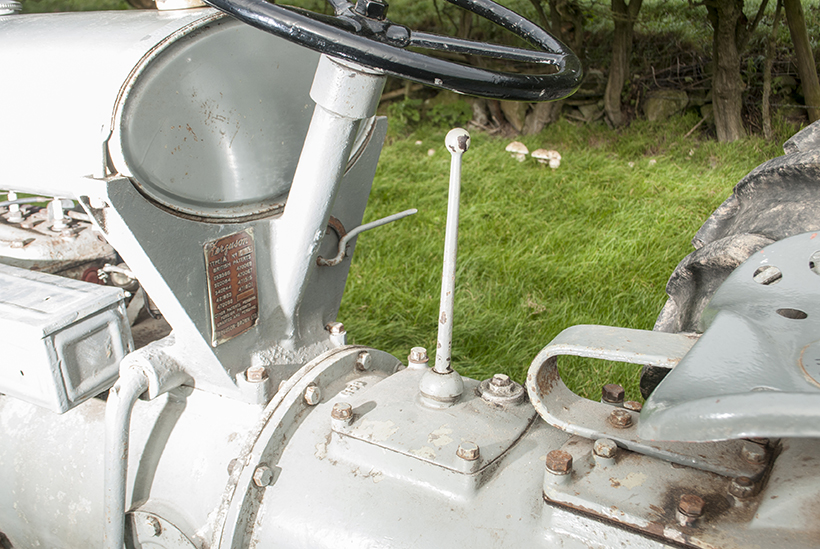

Although Ferguson experimented with power-take-off systems throughout the era of the Type A, this basic tractor has a very simple back axle casting.

Given his early experiences with tractors from the First World War era, Harry Ferguson was determined that his tractors should be lighter. With this in mind, he decided to build his machinery from materials which offered strength without unnecessary weight. The distinctive, cylindrical gearbox, for example, was made from an alloy which saved weight. However, there was a limit to its structural strength, as James was to find after the tractor had given a decade of good service. “The strain of all the work caused the top cover to break, and the threads for the bolts pulled out of the housing. This resulted in the tractor being parked in the shed for a couple of years.

“In 1949, my father bought a replacement Ferguson – a TE-A 20 – which was the petrol-engined model. It hadn’t been here for very long when he let me drive it up the lane, and that was the start of my tractor driving. I must have been about nine or 10 years old at the time. My father had lots of driving experience, right back from the days when he bought his first lorry, but it was easier for a younger person to learn tractor-driving skills. So it was often the case that farmers’ sons found themselves in the tractor driving seat at an early age.”

Blacksmith to the rescue

“While the blacksmith was in the yard one day looking at the Ferguson Brown, he mentioned to my father that he might be able to fix it. Aluminium isn’t easy to work with, but the blacksmith was happy to take on the challenge, and so the tractor was moved to his shop. He managed to weld it all together satisfactorily, after which the tractor remained in regular use on the farm until the mid-1950s. “Around that time, the TE-A 20 was converted to run on TVO since it was ‘thirsty’ compared to the Fergie Brown. Five gallons was enough fuel for a full day’s work on the old tractor, but the TE-A 20 used much more. The conversion kit was produced by a firm called Taggart, but it wasn’t the best. The small petrol tank was mounted on the radius arm where the tool box was, and if you weren’t careful to make sure the fuel tap was turned fully across when you switched over to TVO, the fuel would run backwards into the petrol bowl, then on into the petrol tank. Then, if you stopped the tractor, you had to drain the wee tank and walk back to the yard for more petrol before you could start it again.

Before the invention of this ingenious adjustable front axle, which appeared on the Ford-Ferguson 9N, the wheel width was adjusted for row crop by using spacers.

“Time had moved on, and the Ferguson Brown’s limitations were obvious when you compared it to a TE-A 20 which had more power, more speed and a PTO which was becoming ever more important. So the old tractor was retired and parked in the shed until the 1970s.”

Other machinery from Ferguson and Massey Ferguson appeared on the Adams farm, including another TE-A 20, which had been converted to run on TVO, this time using a Fishleigh kit (a more satisfactory arrangement with the small petrol tank beside the battery), an MF 165 in 1967, an MF 31 combine with an 8ft header and, finally, an MF 575. Sometime later, James handed the reins to his son David, who now runs the farm.

This is a very basic operator’s platform. A steering wheel, a gear stick, a throttle and a seat; what more do you need?

Sympathetic restoration

Back in the early 1970s, when the vintage movement was taking off, James decided to assess his old Ferguson Brown. “It had been driven until, one day, it just stopped. So it was clear that it would need an engine rebuild. The first Ferguson Browns were fitted with a Coventry Climax engine, but this one has the later – but very similar – David Brown motor, with the spark plugs spaced equally along the head (unlike the paired plugs of the Climax engine).

“Since the engine uses white metal bearings, it wasn’t just as simple as fitting new shells. The block had to have the new bearing material applied, then it had to be line-bored to finish the mains to the correct size. We couldn’t find the correct replacement pistons, but managed to source a set which fitted once the tops had been milled to the correct dimensions. Next the valve seats were recut and new valves and guides were installed. There was never a great oil feed to the governors on the Fergie Brown engines, so that needed a rebuild and I fitted an oil pressure gauge for peace of mind.

This tractor was new in 1938; the driver was new in 1939. Both are still in very sound condition, and capable of a day’s work!

“The clutch plate had to be re-lined, but the transmission itself was fine, and the blacksmith’s repair on the hydraulics still held. It was painted at the time of that repair but, given that that was nearly 50 years ago, the paint has faded and is flaking in places. But that’s the way I intend to keep it.

“The tractor still has the original top link and the original pins to go with it, but there’s another story to tell there. One of the top link pins was lost when we were ploughing a field with the tractor during its working life. The field stayed in grass until we ploughed it again 40 years later, and it was during that process that the pin was spotted in one of the furrows. Amazingly, despite being buried in the ground for all those years, it reappeared with the original chrome as good as new!”

This ground is drier than the field where Harry Ferguson first demonstrated the tractor to James Adams senior. Here, James demonstrates the capabilities of this remarkable example of Ferguson design history.

James has done a bit of match ploughing with the tractor in recent years but, nowadays, takes it to local working days and gives it a day’s work, just as Harry Ferguson intended. However, he’s careful to keep a better eye out for the wet corners!

This feature comes from the latest issue of Classic Massey & Ferguson Enthusiast, and you can get a money-saving subscription to this magazine simply by clicking HERE

Previous Post

What’s to be found in the excellent Dover Transport Museum?

Next Post

The latest diecast and resin models of classics to collect