BMC’s Austin and Morris light vans from the 1950s and ’60s

Posted by Chris Graham on 18th November 2022

Peter Simpson compares and contrasts BMC’s Austin and Morris light vans from the 1950s and ’60s, from a buyer’s viewpoint.

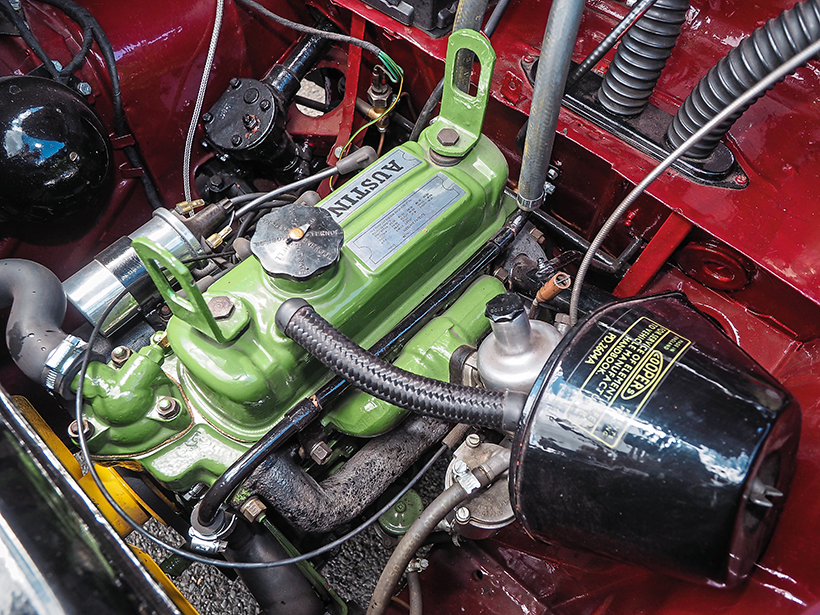

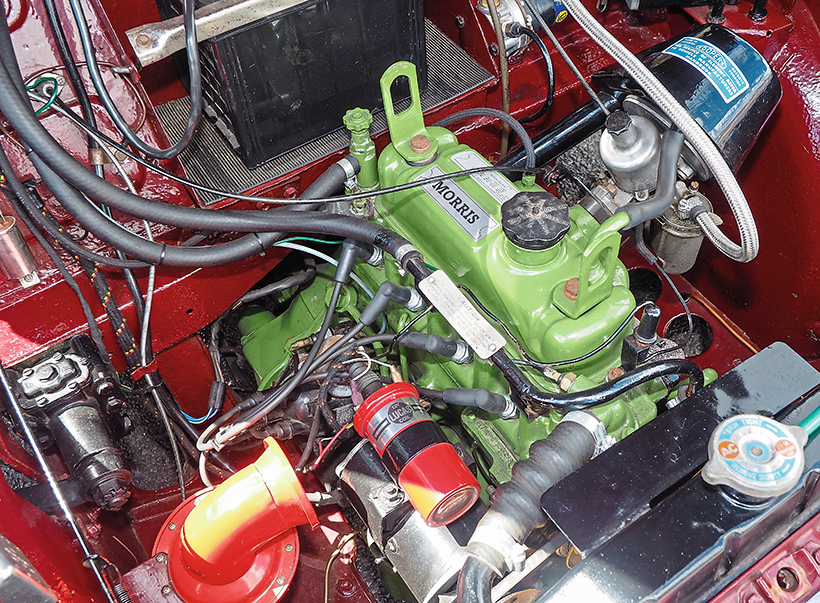

Austin and Morris light vans: This Morris 6cwt van dates from 1961 and has the 948cc A-Series engine.

For most of the 1950s and ’60s. the British Motor Corporation (BMC) was the overwhelmingly dominant force in the British car market. Yes, there were others, but BMC was the British make and, for most buyers, the natural choice. And in no sector was this more true than the light van market. GM/Vauxhall wasn’t in the sub-10cwt sector at all until 1964 and, until the Anglia-based van arrived in 1961, Ford’s light vans were pretty archaic, although, despite being limited to 30mph except on motorways, this wasn’t as big an issue as it may sound. Rootes had its Commer Cob family, but though a good van, this was a bit dearer than BMC’s offerings, and the dealer network was smaller.

BMC’s dealer network, by contrast, was vast. When Austin and Morris merged to form BMC in 1952, both constituents had nationwide coverage with a dealer in every town and most rural communities. With the merger, 90% of these places found themselves with two BMC dealerships; one Austin, one Morris and, locally, these would still be competing for sales. As is well-known, BMC’s short-term solution for this – which lasted around 20 years – was to produce Austin- and Morris-badged versions of the same basic car, hence the Austin Cambridge and Morris Oxford, and the Austin- and Morris-badged Minis, 1100/1300s and 1800/2200s.

This 1967 Austin A35 6cwt van was built in the final year of production. The front doors appear to be from an earlier vehicle as the indentations were dropped in 1962.

When it came to vans, however, Austin and Morris dealership’ RWD offerings were definitely different – Austin dealers sold the A35 van, Morris dealers the Morris Minor-derived Morris ¼-ton van. Both also had Mini-derived vans with Austin or Morris badging as appropriate, and these were both known as Mini ¼-ton vans – presumably because Mini was new and exciting and/or to distinguish them beyond any doubt from the RWD versions.

So why was there any need for the old-school RWD 6cwt vans at all, when Austin and Morris dealerships both had access to a Mini-based van? Well, the issue was that FWD was still very new technology, and early Minis had quite a few teething troubles! Consequently, many van buyers decided front wheel drive wasn’t for them, and if BMC couldn’t supply a conventional option, they would have to look elsewhere. Thus, van versions of RWD cars introduced in 1948 and 1952 remained available, until 1972 and 1968 respectively.

Both vans had BMC A-Series engines of varying…

A bit of history

Though the Morris Minor saloon was introduced in 1948, it was to be another five years before the van version arrived, in May 1953 – by which time the ancient Morris sidevalve engine had been replaced by the 803cc version of BMC’s A Series. In 1956 a 948cc version of the same engine came along and, in 1962, it went to 1,098cc and stayed there until production ended in early 1972. With the 1,098cc engine, the payload was increased from 5cwt to 6cwt; for those of us brought-up on metric weights and measures, there are 20 hundredweight or cwt to an imperial ton. However, the Post Office (the biggest and best-known user of Minor-derived vans) stuck with the 803cc engine until 1962, when it went straight to 1,098.

Though clearly Minor car-derived, the commercials were totally different structurally, and had a separate chassis, though the torsion bar front suspension and rack-and-pinion steering were retained. Rear suspension, however, had telescopic rather than lever-arm shock absorbers. The cab and body were separate pressings, bolted to the chassis and with a rubber draft-strip between them. All-in-all, the Morris van was pretty advanced by the standards of the time. There were various detail changes over the production run, such as a single windscreen replacing the previous split-screen type with the engine size change in 1956, and larger rear windows from 1962, plus some changes that were required by legislation such as white and amber combined sidelights/direction indicators from 1964.

… but usually comparable capacities through the production run.

From April 1968, an 8cwt version of the Morris 6cwt van was offered – possibly in response to Ford’s new Escort-based van being available with 6cwt and 8cwt payloads, instead of the Anglia-based vans’ 5cwt and 7cwt. This upgrade was achieved through upgraded rear suspension and bigger tyres. The previous month (March), an identical – apart from the badging – Austin version of the same van was offered so that, Austin-only dealers would still have a RWD light van to offer after the A35 was discontinued. From 1971, the final few Austin- and Morris-badged vans had a combined steering column lock and ignition switch.

The A30 van arrived on the scene in August 1954 with, again, the 803cc version BMC A Series engine. Unlike the Morris, which had an SU carburettor (SU being owned by Nuffield/Morris), the A30 followed the Austin tradition with a Zenith carburettor. The A30 was very traditional Austin elsewhere, featuring safe but unadventurous engineering. One aspect was, however, old-hat already and would become increasingly so; the brakes were only part-hydraulic. At the front, the system was hydraulic, but the hydraulic circuit stopped half-way down with a single frame cylinder to which rods were attached to operate the back brakes. In truth, this system was probably fine for a very modest performance vehicle operating in typical 1950s road conditions, though it did need looking after. By the 1960s, however, it was something of an anachronism.

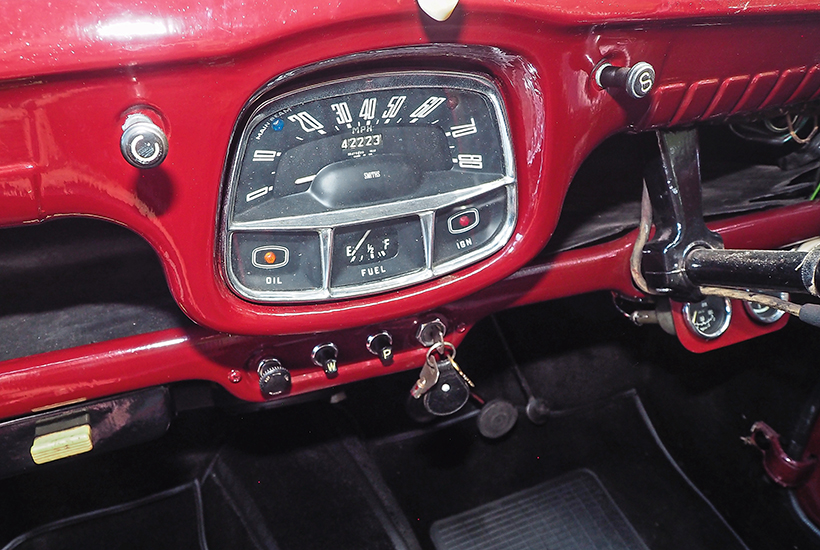

Both vans have centre-mounted instruments; this was common on low-cost vehicles as it makes manufacturing LHD and RHD versions rather more straightforward. This is the A35 – the starter switch (right of speedo) is a pull-knob acting directly on the high-power switch on the other side of the bulkhead; there’s no starter solenoid, and the key-switch just turns the ignition on and off.

The A30 gave way to the A35 in October 1956 when, like the Morris van, the Austin received the 948cc A-Series engine and, with it, a shorter and more precise remote-action gearchange. Unlike the cars, however, the A35 vans retained semaphore-style direction indicators. Outside, the big change was that the A30’s chrome radiator grille gave way to a painted one. In 1959 the A35 saloons were discontinued – replaced by the Mini and, for those who still wanted RWD, Farina-styled A40. However, the vans (and the van-based Countryman estate car) remained in production and, in February 1962, were given a slight facelift – plain side door exterior panels replaced the previous design with two indentations, and flashing direction indicators finally arrived. That September, however, a bigger change was made when the 1,098cc A Series engine replaced the 948 unit, with the drivetrain modified to suit. At the same time, BMC replaced the bought-in Zenith carburettor with its in-house SU.

Despite being a low-compression engine, and perfectly happy on two-star petrol, the 1,098cc A35 van was the fastest of all the A35 family – a top speed of 80mph was claimed. This didn’t go unnoticed by one potential fleet buyer, Great Universal Stores, but not for the right reason – it was considered too fast, and the company requested a less powerful version for local delivery work. BMC responded with an 848cc version which went on general sale from August 1964. Though the 848cc A Series was very familiar as the Mini’s base-capacity unit, this was the only RWD version made, and it seems odd that BMC would bother engineering this at all without something else in mind – a RWD Mini-type car perhaps? For just under two years, the 848 and 1,098cc options ran alongside each other, but the 1,098cc version was dropped in May 1966, with 848cc A35 van production ending in February 1968.

The Minor van’s cab is slightly wider than the A35’s, giving a little more elbow room. Extra instruments were a common addition by enthusiasts back in the day; neither the Minor or the A35 came with a temperature gauge.

In total, around 326,000 Minor commercials were made, compared to 236,622 A30/A35s. Interestingly though, out of 210,575 A35 vans, 122,820 were made between 1960 and 1968, after the cars had been discontinued in 1959. 1960/61 was the van’s best-selling year of all, with 34,257 sold that year. After that, of course, the Mini van was also available.

Business buyer’s choice

As noted a moment ago, the key reason for BMC producing Austin- and Morris-badged versions of almost identical vehicles was the still-separate dealer networks, and many places having locally-competing Austin and Morris dealers. There was also a lot more dealer-loyalty back then anyway and, of course, the core market for light vans would be local businesses, the proprietors of which would quite likely mix in the same social circles as the owners of the local dealerships. ‘Connections’ and ‘unusual’ handshakes would often play a significant part!

From a driveability point of view, the Morris wins hands-down – well in most respects, anyway! The steering is more precise, the handling feels better and, of course, the all-hydraulic brakes are superior, though actual braking performance when new and in perfect condition isn’t as different as might be expected. The 1,098cc A35s do, though, score in one respect – speed! Both 1,098cc vans had 45hp on tap. But with a kerb weight of 686kg compared to the Morris’s 779kg, the Austin’s power-to-weight ratio was significantly more favourable. This also gave it marginally better economy on paper, although the real-world difference was probably more down to load and driving style.

The Morris’s loadspace, and a non-original but very nice floor covering. Good, but having the spare wheel fitted inside could be a bit awkward is a puncture occurred when the van was fully loaded.

For a commercial buyer, price is an important consideration, and here it’s quite hard to make an accurate comparison as there are so many variables and options; even a top coat of paint was an option. Not everything that could be had or not had was listed either! However, from looking at contemporary advertisements and so on, it seems that like-for-like, the Morris was slightly more expensive. In 1961, a 948cc A35 van cost £368.10 on the road, and the comparable Morris just under £400. However, the Morris also has one big advantage; thanks to its chassis-based construction, it could be bought as a van, pick-up, or as a chassis cab unit (with or without a cab back) for fitting with specialist, bespoke bodywork.

From a practical point of view, both vans had good and bad points. Loadspaces are roughly comparable at 50-60cu.ft – the 10cu.ft difference being down to whether you count space released by choosing not to have a passenger seat. The Morris’s, however, was wider and probably easier to access through the two doors.

However, the A30/A35 had one advantage which anyone who has had to change a wheel on a laden van just once would probably give a lot of credit for; its spare wheel is stowed neatly in its own compartment under the load floor and immediately accessible with the rear door open. The Morris’s, by contrast, sits inside the van and, although it comes out through the cab, that’s likely to be far more awkward with a loaded vehicle.

The A30/A35’s loadspace is a similar size overall, and here the spare wheel sits underneath.

At the end of the day, it was horses for courses, and buyers would no doubt choose the one that met their needs best, or the one offered by the dealer they knew best. The point, though, is that in stark contrast to BMC car buyers at the time, van buyers had a genuine choice of genuinely different vehicles.

The choice today

Today, the Morris is more plentiful in preservation, and certainly enjoys the stronger commercial support – in fact it’s better than for some modern vehicles! Pretty-much anything can be obtained – even a new chassis – and there is a choice of suppliers. But having said that, the A30/A35 range is also well-served, and the range of parts is very, very good indeed. In fact, at least one long-established Morris Minor parts specialist – ESM Morris Minors of East Sussex – now supply A30/A35 stuff as well. The main difference is that whereas new panels are often available for Minors, with the Austins it’s generally a case of using repair panels to restore what you have or, finding a better secondhand item to repair.

The single-piece A35 van’s rear door featuring the ‘Austin of England’ logo.

In terms of actual restoration, the big problem area for both is corrosion around the guttering; it might not look like much, but welding this back up is skilled stuff! On the Morris, the chassis itself can corrode, along with the body supports, floorpan and inner wings, plus the van body lower sections, inner arches and load floor at the outer edges, especially at the back. With A30/A35s, the unitary construction means the sills are 100% structural, and other common problems include the front panel either side of the grille, low down at the back, floor corners and rear spring mounting points. Look at a list of available repair sections for a complete list of the typical rot-spots! Mechanically, both vehicles are pretty similar and pretty durable, though the rear axles are different, and the A35 half-shafts can fail at the inner end where they slot into the differential unit; fitting another shaft when free play and clonking starts is easier than waiting until it breaks, when you’ll probably have to take the diff out in order to extract the broken-off end.

The Minor van had double rear doors. The rear windows were enlarged from 1962.

These days, a lot of Minor and A30/A35 vans have been upgraded, and there’s quite a lot that can be done. 1,275cc A-Series engine conversions are common, though these days sourcing a suitable engine might be the hardest part. Because it was designed with a flat-four engine in mind, the Minor engine bay can take a wide variety of alternative power sources. Upgrading dynamos to alternators is also straightforward, and recommended if additional electrics are fitted. Many people have also chosen to upgrade A35 brakes, and this is essential if any power upgrade is being considered; there are various ways of doing this; at one time the go-to method was to bolt on an A40 Mk2 system, or adapt and bolt-on MG Midget brakes, but again, the parts to do this aren’t now as easy to find as at one time.

The famous, ‘Flying A’ symbol on A35 bonnets doubles as a bonnet-release handle.

So which is best? Both vans have their plus and minus points, and now, just as it was when the vans were current, the choice will probably come down to personal preferences. Some may regard the slightly quirkier looks and character of the A35 – together with its relative scarcity – as more than cancelling out the slightly poorer driveability and marginally more difficult ownership experience. Others may prefer something that’s nicer to drive and with a choice of parts and service suppliers only a keyboard or phone call away. But there is a real choice here that goes far beyond different badges.

This feature comes from the latest issue of Classic & Vintage Commercials, and you can get a money-saving subscription to this magazine simply by clicking HERE

Previous Post

1940s steam tug nears end of the line

Next Post

Sentinel steam wagons return to a famous site!