An unnerving underwater threat

Posted by Chris Graham on 27th January 2020

Mike Williams tells the fascinating story of how the suggestion of an unnerving underwater threat nearly proved disastrous for the British Navy in the apparently secure Cromarty Firth of 1914

An unnerving underwater threat faced the mighty dreadnoughts of the British Grand Fleet (GF), and was brought home in the most telling fashion conceivable on September 23rd, 1914. That fateful day the armoured-cruisers Aboukir, Hogue and Cressy – all of the 7th Cruiser Squadron – where sunk off the Mass lightship with the loss of 1,459 men, by Commander Otto Weddigen’s U-9. A single, small, coastal submarine had destroyed an entire squadron of capital-ships.

Admiral Sir John Jellicoe, in command of the massed GF, had the unenviable task of containing the German High Seas Fleet within its home waters. He set about this by imposing a distant blockade that demanded exposed cruiser sweeps of the contested North Sea. It was an exhausting process that weighed heavily on both men and machines.

U-boat threat

The enhanced and growing perception of the abilities and potential of U-boats to attack GF shipping wherever they went (even when in harbour), generated enough fear to drive even the mighty GF to an improvised base, at Loch-na-Keal on Mull, from its main Scapa Flow anchorage. This move followed a number of U-boat scares around the Orkney’s.

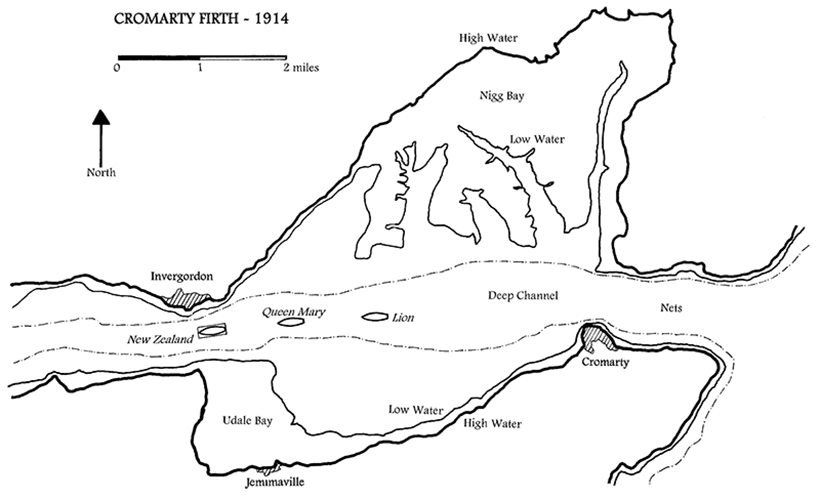

In late October 1914, the 1st Battle Cruiser Squadron (1BCS) of the GF, formed around the Flagship of the dashing Vice-Admiral Sir David Beatty’s Lion, along with Queen Mary and New Zealand, accompanied by their screen of light cruisers and phalanx of destroyers, which had been on yet another sweep of the contested North Sea, and were ordered to head for the supposedly secure and important forward GF base at Invergordon, in the Cromarty Firth. The purpose was to allow them to coal and get some much needed rest, with Scapa Flow still deemed too open and vulnerable to surprise attack after yet another submarine scare there on October 17th.

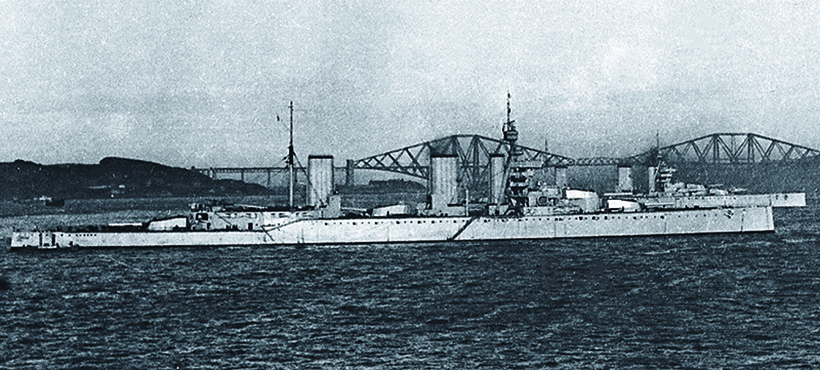

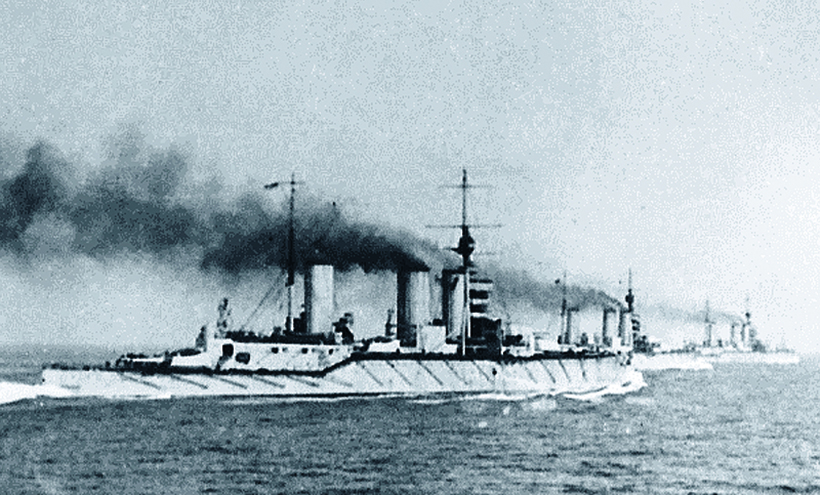

A striking view of the battle-cruiser Queen Mary, capturing her at the Fleet Review in late July 1914, just before the outbreak of the First World War

In relating what was to follow, it’s very fortunate for posterity that the telling, personal recollections of two individuals on board Queen Mary have survived. Serving under the command of Captain Rudolf Bentinck, Major Gerald Rooney (Royal Marines), and Midshipman Arthur Bagot, saw fit to record the ensuing events, and their accounts have been extensively incorporated into the fabric of this tale. I’ve drawn heavily upon these eye-witness accounts in my efforts to finally discover exactly what actually transpired.

Cromarty Firth arrival

On Sunday the 25th, Queen Mary and her companions entered Cromarty Firth during the morning watch, and moved up to lay-off Invergordon, where she anchored and allowed the collier Holmpark to come alongside with 1,600 tons of coal. In a letter, Beatty gave a very good indication of how well employed his ships had been since the outbreak of war, by mentioning that his squadron had steamed 5,400 miles at sea during August, and around 6,000 miles during each of the following two months. He also commented upon how his ‘Great Coal Eaters’ had required to undertake coaling evolutions on average every four days, because of this demanding time at sea.

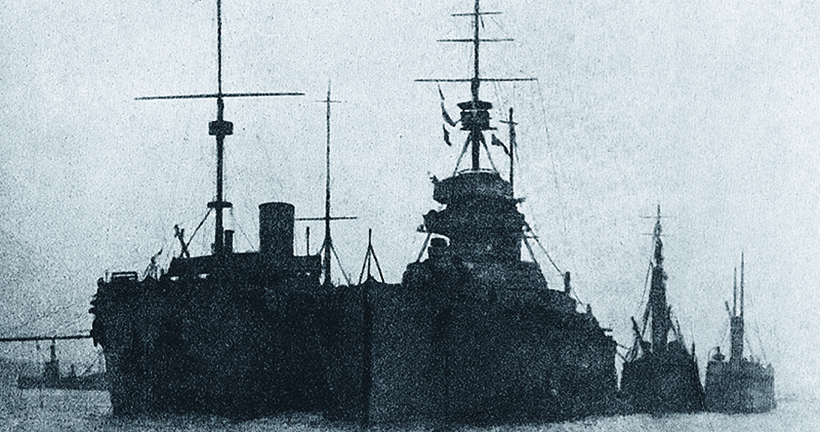

An unidentified Bellerophon-class dreadnought entering Cromarty Firth, as seen from the Sutors of Cromarty at the entrance. What the extent and nature of the hurriedly provided late 1914 defences were has been impossible to determine

On that distant Monday afternoon of October 26th, 1914, in the early phase of the First World War, there occurred a little-known incident that’s long forgotten for most. An event which clearly demonstrated the nervousness – and feeling of acute vulnerability – that the mighty capital ships of the GF felt regarding one arm of the elusive German Navy; its U-boats.

In this affair, paradoxically, the public’s very favourable perception towards the vigilance of the ships involved, and their capacity to defend themselves, was directly countered by the Royal Navy’s recognition of their inabilities to oppose such a threat, when the anchored ships of the 1BCS opened fire at a ‘sighting’ off Invergordon, in what would later become known to a select few as ‘The Battle of Cromarty’.

Onboard Queen Mary, hands had been called at 06.10 to clean ship, in preparation for what was thought to be yet another routine day in harbour. Lion had secured the store ship Calder alongside at 06.20, ready to embark supplies and casting her off again at 10.20. The general scene inside the wide expanse of Cromarty Firth on that day saw the three battle-cruisers of the 1BCS, undertake routine service and domestic matters, sheltered and at peace within the protected confines of this defended anchorage, with their own anti-torpedo nets deployed.

Uneventful start

From the viewpoint of Queen Mary, New Zealand was in the dry-dock, floating about half a mile away just to the west, off Invergordon Ferry, while Lion lay astern of her in the deep water channel to the south-east of the town. This morning had been an uneventful and customary one for the moored 1BCS, but all that was to change soon after midday.

Present at Cromarty on the day of the ‘Battle’, Lion, the renowned early war flagship of Admiral Beatty, which fought at all the major naval actions of the First World War in this celebrated capacity

At around 12.15, a signal was received on board Queen Mary from the Flagship, warning that a submarine was purportedly within the Firth. Speculation on the bridge noted that it might have followed a steamer into the anchorage, upon which Captain Bentinck ordered that red watch man her aft, 4in gun battery, nearest the Firth’s entrance. However, apart from this precaution, somewhat inexplicably, no further action taken at this stage.

Queen Mary carried 16 4in pieces in two, eight-gun batteries in single casements. Both these groupings where carried on the forecastle deck, in well-appointed firing positions, with a concentration of no less than six pieces ahead, four astern, and eight on either beam being possible. The only negative factor about this outfit was that many considered its 25-pound projectile to be too light to counter German torpedo-boats, although they were deemed more than capable of dispatching a U-boat.

Shortly afterwards, blue watch was called to man the forward 4in gun battery, but there was seemingly a great deal of delay in getting these guns manned. Two messages were sent to the quartermaster to have this piped, without any effect but, eventually, the guns were manned. By 12:30, all the Queen Mary’s secondary batteries (and supporting, spotting, five Maxim machine-guns) were closed-up on board the generally accepted crack gunnery ship of the 1BCS.

Slow reaction

This usually lackadaisical mood was in direct contrast to the predictable, extreme reaction that such a sighting in Scapa Flow had upon the GF, and the inevitably tremendous commotion it produced there. So, this initially slow reaction to the potential danger at Cromarty was particularly strange. The most obvious sign of a stirring within the Firth, was the raising of steam among the 40 or so supporting trawlers and drifters in the anchorage before the ‘action’ opened, with a marked discrepancy in times between two official sources.

Also present at Cromarty in late October 1914 was New Zealand, a much-valued gift from a loyal Dominion, seen here late in the war with a number of important physical changes to her structure

Queen Mary’s logbook records: ‘12.30 open fire with 4in guns on supposed submarine’, while that of Lion notes: ‘12.57 opened fire with 4in guns at an object which appeared to be a submarine’, before noting her cease fire at 13.03. No explanation for these marked discrepancies has been discovered, but a telling indication of the effect of such gunfire can be drawn from the following two personal extracts, which only confuse the entire chronological sequence of events still further.

‘I gave the 4in guns a range of 1,000yds, zero deflection, and the gunnery lieutenant came up and decided to put everything to zero, so as to get a flat trajectory. About 12.30 or 12.20, the signalman of watch called out, ‘there’s a submarine, sir’, the lookout reported it at the same time, and there was a general shout from below of ‘There she is’.

Submarine alert!

‘Over on the south side of the firth, about 900 to 1,000yds off, and heading straight up towards New Zealand in the floating dock, a submerged object, or a submarine, appeared. It was moving at about 10kts, and throwing up a jet of water from her periscope or conning tower, to a height of three or four feet. About 20ft abaft this, another spurt of spray was being flung up. Through glasses I could not discern any periscope, but the upper portion of a conning tower appeared to be throwing up the water in a forward direction. I gave the order to the signalman to fire the spotting maxim at it and, immediately, gave the order to sound the alarm, with the bearing ‘red 90’, and, about 10 seconds afterwards, open fire. The fore battery opened almost at once, also the after battery, under the first lieutenant. The rounds fell about halfway, 500yds off, and the guns got the range by degrees, but the firing was undoubtedly very bad, the ranges given being by no means good, so fire was much scattered’. (Rooney)

‘13.00 Wave seen moving up harbour abeam of us at 200 to 300yds, about 12kts. Opened fire, ditto Lion. Maxim gun hit straight away. Shots ricocheted into village and wood opposite. Fired about three or four rounds from each gun’. (Bagot)

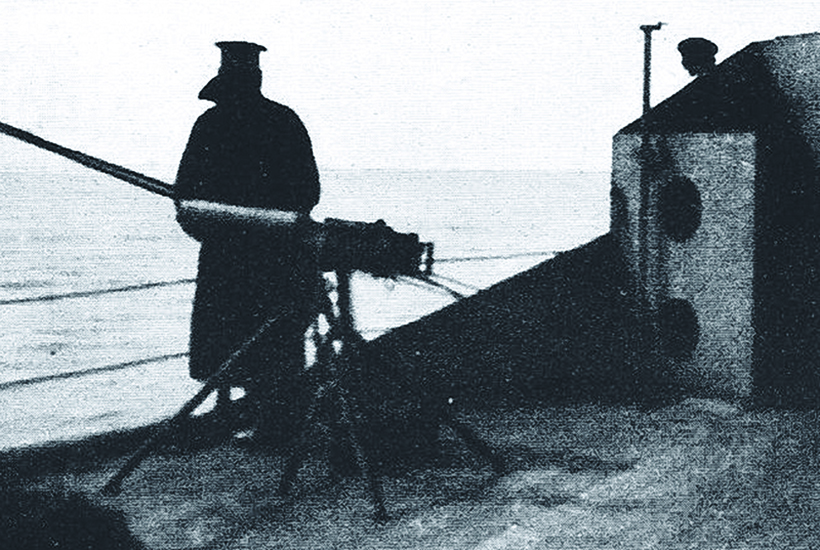

A rare image of a Maxim machine-gun on a rudimentary mounting on board a British capital ship in harbour, with the watch looking out for any threat. Examples of these guns were much employed for the spotting and direction of Queen Mary and Lion’s secondary batteries at the ‘Battle of Cromarty’

Midshipman Bagot’s observations appear to have had under-estimated the range, but indicates that approximately 30, 4in shells, were dispatched by Queen Mary’s portside secondary batteries at this ‘target’, guided by spotting machine-gun fire. Presumably, Lion’s fire was of a similar weight, in an estimated five-minute fusillade. Obviously, the poor performance revealed in Queen Mary’s secondary armament shoot earlier on the 8th of that month with New Zealand, had still not been corrected in the short span of time granted their crews. It was immediately accepted that this defensive fire had been badly directed with potentially very serious collateral effects ashore.

Inaccurate aim

‘The Lion also opened fire lamentably short at first, all the firing seemed wild. The Maxim also jammed, but its spotting duty was complete. The shots from the 4in ricocheted in shore, and commenced to burst on the beach, in the woods and on the hillside, in a dangerous manner, especially when the wash passed abeam. The shells apparently passed over or through the little village of Jemimaville’. (Rooney)

A nice postcard view of Jamimaville in the halcyon days of peace during 1920, capturing its quite charm. Presumably, little changed despite its shattering experience in late 1914 at the hands of the 1BCS

It is conveyed that Queen Mary ceased firing at 13.04, only as the wave of the ‘target’ disappeared, as concern was now directed towards the southern shore, especially where the ricochets and overs from the squadron’s fire had appeared to have fallen in and around the hamlet of Jemimaville; a small village on the northern coast of the Black Isle overlooking the Firth.

On the bridge of Queen Mary, Captain Bentinck, Commander Llewelyn, Lieutenants Scholtz, Cowan and Ewart, along with Major Rooney, had witnessed this dangerous ‘friendly’ fire landing on shore. Bentinck ordered a cease fire even as Lion purportedly continued, as he was inclined to think it was the wash of a destroyer which had passed up some time previously, but the majority on the bridge were still certain that the object was a submarine.

Firing orders

One vital issue needs to be highlighted, and that’s that no record mentions – or even alludes to – who ordered the firing to commence. It appears that Lion opened fire first, but there’s been no authoritative verification of this. Indeed, a query came from Lion to ascertain what had actually been fired upon, with the Admiral himself stating that he considered that it had looked like the wash of a destroyer, immediately confirming Bentinck’s impression, as the drama still continued but, this time, sanity prevailed.

‘An alarm was now raised from the upper deck, that the ‘submarine’ was visible again, still to the southward, passing down harbour, and the guns were trained in that direction, but the captain gave the order, very wisely, not to open fire without his permission. Invergordon pier was now crowded with town folk, and all the shipping crowded with men, picket boats were swarming around, and tugs and destroyers stood by the floating dock to beat of any attack. But nothing more appeared’. (Rooney)

It’s striking to note the telling discrepancies in rendered times clearly noted in all official and private sources. But, from weighing-up all accounts, it’s perhaps reasonable to conclude that, after an initial sighting around 12:15 – presumably from Lion – the ships of the 1BCS went to man the secondary armament in a markedly measured fashion by 12.30. They eventually opened fire on a fleeting and elusive ‘target’ that was slowly travelling up the Firth for an approximately ragged five-minute barrage shortly after 12:55, with all fire ceasing by 13:05 as the object faded. I believe this to be a credible summation of this incident’s timeline.

Captain Bentinck stood by his contention that it was a wash; he saw no periscope. But Engineer-Commander Rattey said he actually saw one foot of periscope, while Commanders James and Pennell actually ‘observed’ a torpedo and Lieutenants O’Manny and Ewart only spotted wash on a bank. But Cowan was certain it was a submarine, while the enlisted signalmen, and lookouts on the bridge, were also all convinced it had been a submarine.

A superb study of Queen Mary’s near sisters, Lion and Princess Royal at anchor off Rosyth, the famous lair of Beatty’s ‘Big Cats’, the GF’s battle-cruisers. These three capital ships were very similar and are difficult to differentiate, but Queen Mary from the building programme following her sisters possessed a far more ‘rounded’ central funnel than the ‘flat’ example in the others as perhaps her most prominent distinguishing external feature

Damage ashore?

A landing party from Queen Mary was eventually mustered and sent ashore at 15.30, where they found a few villagers and quickly established what had occurred at Jemimaville. Critically, the village, although hit, had miraculously escaped serious damage and, more importantly, there were no fatalities. However, there was one, very serious casualty. A couple of the houses had perforated upper-works and, in one case, a 4in shell had gone through the apex of the roof and passed out the other side, sending slates flying everywhere.

But herein lay a very personal tragedy; an individual whose life was to be inexorably changed through the events of that day, and the effects of this one shell. Had it not been for the consummate skill of the local doctor, the incident would have ended in tragedy.

Baby Alexandria McGill, just 10 months old, was lying in her cradle when the shell arrived. Fortunately, the cradle included a sturdy, wooden hood and, when the whole second floor of the house fell in, the cradle withstood the weight of a hearthstone that fell across it. When the child was found, neighbours feared the worst as one of her legs was hanging off. But the doctor took charge, cleared her lungs and, later that day, sewed on her little leg, just below the knee.

She had a scar all her life, and one leg was shorter than the other. She never danced, wore a swimsuit or went bare-legged, and remained very self-conscious about the disfigurement throughout her life. The only acknowledgement from the Navy in that pre-compensation age, was a small silver rattle that was shaped like a ship’s bell which was sent. It was inscribed: ‘A present to Baby McGill from HMS Lion, October 1914’.

Wayward shells

This rogue shell that had caused so much damage at the McGill’s house, finally detonated over the road, showering the area in fragments, holing walls and breaking every window in the vicinity. Another couple of wayward shells ploughed their way into the fields about 100yds south of the village, cutting up furrows before bursting. Fortunately, though, the majority of the errant shells fired in the ‘action’ landed harmlessly in nearby woods to the south, or to the edges of the village. No shell fragments could be found by the initial inspection parties, and it was later discovered that relic hunters were quick to descend on the scene after the bombardment, collecting every single piece over the course of the same afternoon.

So ended the incident as far as the Royal Navy was concerned but, within the 1BCS, there was some soul searching regarding an explanation about what had actually happened. Manifest to all within the 1BCS, was the palpably poor level of accurate 4in defensive gunnery displayed and, to correct this, an improved degree of gunnery training and practice shoots was arranged soon afterwards. So, there was, at least, one positive and noteworthy service benefit derived from this fiasco.

Given that day’s events in the in the Cromarty Firth, the story continued within the 1BCS, especially on the lower deck where endless yarns arose, all based upon a supposition that the submarine was imbedded in the mud bank to the south in Udale Bay, and would eventually come to light one day.

‘In the dark’

While such rumours where tolerated within the 1BCS, it became accepted by all service personnel concerned that, as far as possible, the general public was to be kept ‘in the dark’ about this particular, embarrassing naval episode. Nothing was to be said about it, even in the Admiral of the GFs usually detailed post-war coverage of the First World War. Accordingly, he only dedicated a very brief and dismissive passage to this entire event: ‘On the 26th, a submarine was reported inside Cromarty harbour, but Sir David Beatty, who was there with the battle-cruisers stated, after investigation, that he did not consider the report was true’. (Jellicoe)

Indeed, the very brief logbook entries from Lion and Queen Mary, were all that was officially penned by the bridge personnel; strangely inconsequential and non-informative, given the extremely unusual nature of the whole episode. But, obviously, such highly-visible goings on could not be completely covered up, especially among the many civilian witnesses. That very evening, in fact, the stop-press column of the Inverness Courier carried the first public mention of the event.

Here it was announced that a number of reports had reached the paper’s office from Invergordon and Dingwall, to the effect that German submarines (note the plural) had broken into Cromarty Firth, and where subsequently heavily engaged by British warships. It was also believed two of the hostile submarines had been sunk.

Press interest

Although it was admitted that no official confirmation of the report was available, there was undoubtedly heavy firing going on in Cromarty Firth for several hours (although just five minutes seems likely from my investigation), and that great excitement reigned not only in Invergordon, but all the towns and villages along the Firth. It was confirmed that the paper had elicited these ‘facts’ from several independent eye-witnesses, one of whom added that he understood considerable damage was done to buildings on the Cromarty side of the Firth by the firing; a vital and correct point among many speculative and second-hand accounts.

The Inverness Courier persisted with its investigations into this important local story and, the following day, it ran a far more revealing piece titled, ‘Rumoured Submarine Attack – Excitement in the North’. This included plenty of general praise and pleasure from the locals about how the 1BCS had proved to be so vigilant and, apparently, very effective in the manner in which it had performed.

Obviously, the confused and inaccurate firing by the battle-cruisers was not apparent to those on shore, only the general impression of the ships beating off the enemy in a proficient fashion, as it appeared to the distant, civilian observers.

However, there was, by then, some understandably fervent official discomfiture over the event. Major Rooney wrote: ‘A full and wonderful account appeared in the Inverness Courier, headed ‘The Battle of Cromarty’, which was promptly suppressed. Also, a tacit understanding that the less said about it the better. But who knows’. From this telling concluding comment, it is perhaps appreciated that while being shrouded in secrecy at that time for obvious profound service considerations during the war, this perceptive participant realised that it should be related in some fashion one day. It now has, due principally to his and Bagot’s invaluable private diary entries.

Unnerving presence

The threat established by enemy submarines, torpedoes and mines was certainly real and would inflict significant if not fatal damage upon many a fine ship of the Royal Navy throughout the First and Second World Wars. The direct physical impact of such nefarious instruments of destruction were palpable and obvious. But not so apparent was the insidious, psychological influence inherent in such a hidden, underwater menace. The way this could affect minds and, ultimately, the abilities of personnel to perform under such continuous pressure was significant. The submarine threat made it far more difficult for ships crews to act normally. The risk of breaking under the pressure, or acting in an uncharacteristically flustered manner when U-boats were thought to be near – as displayed by the apprehensive and fatigued crews on board the 1BCS at the forgotten ‘Battle of Cromarty’ – was a very real one.

Readers might also like to know what happened to the characters whose experiences and evocative recollections have been so deeply involved in this article, and some of the other identified members of Queen Mary’s crew. In March 1916, Midshipman Arthur Bagot was posted to the sloop Pantranion for service in the Mediterranean, later seeing action in the new destroyer Tirade, sinking UC.55 off the Shetlands in 1917.

Captain Bentinck and Lieutenants Cowan and O’Manny also left Queen Mary for other posts over the following months and undisclosed fates. Regrettably, Major Rooney, Commander Llewelyn, Lieutenants Scholtz and Ewart, where all lost along with this battle-cruiser and 1,266 members of her crew, leaving just 21 survivors after her explosive demise at Jutland, on May 31st, 1916.

Generally credited as being the last photograph to have been taken of the Queen Mary, this evocative image captures a number of interesting points on her last day at Jutland

To subscribe to World of Warships, click here