Amazing, between-the-wars images

Posted by Chris Graham on 6th December 2021

Jim Shaw showcases the amazing, between-the-wars images produced by official Panama Canal photographer, Ernest ‘Red’ Hallen.

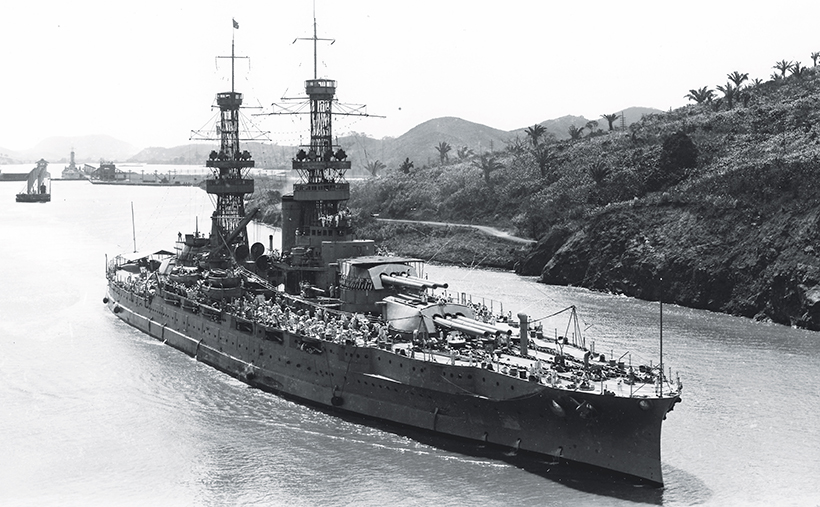

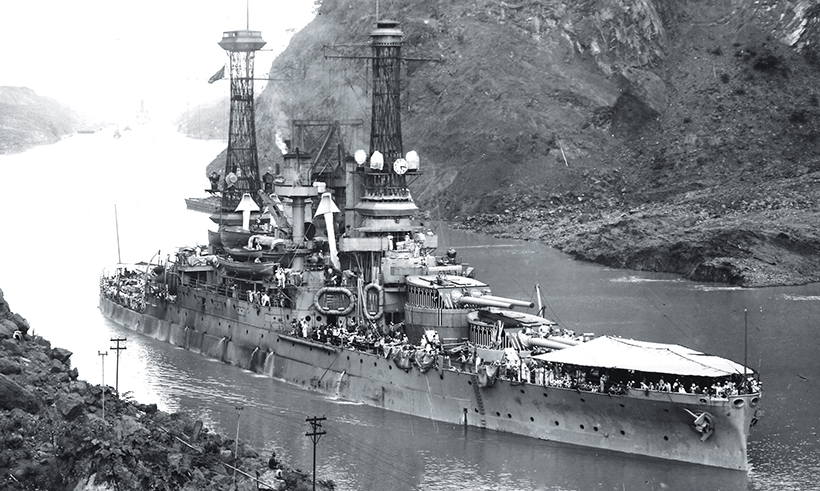

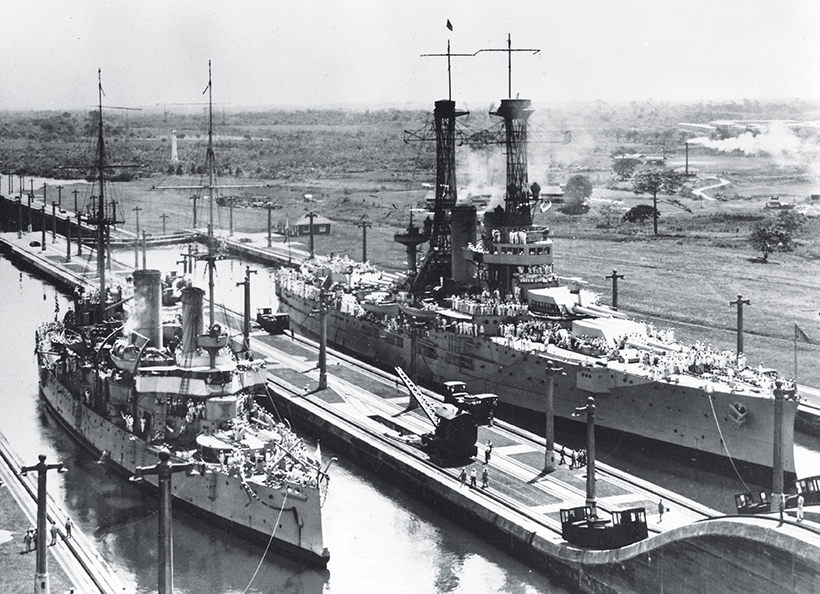

Amazing, between-the-wars images: The battleship Arizona was photographed by Hallen on February 23rd, 1921, while she was transiting with the battleships North Dakota, Delaware, Utah, Pennsylvania and Oklahoma from Callao, Peru to Guantanamo, Cuba. This was prior to a major refit in 1930, when the ship’s corrosion-prone cage masts, were replaced by new, tripod masts and two decades before the attack on Pearl Harbour, during which the American battleship was crippled by a massive internal explosion that killed 1,177 crewmen; almost half of the 2,403 lives lost on that day.

During the decades following the opening of the Panama Canal in 1914, the navies of the world became regular users of the waterway, some sending entire fleets through. The US Navy was paramount, of course, as the long trip around South America by the battleship USS Oregon during the Spanish-American War had been a major factor in America’s decision to build the canal. During the waterway’s planning it had been decided that photography should be used to document all phases of engineering and construction.

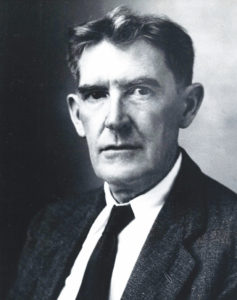

Born in Atlanta, Georgia, in 1875, Ernest ‘Red’ Hallen was appointed the official photographer of the Panama Canal by the Isthmian Canal Commission, in 1907. He retired after 30 years of service, during which time he and his assistant took nearly 16,000 glass plate images of the Panama Canal and its ships. He died in 1947, aged 72.

A 31-year-old professional photographer, Ernest ‘Red’ Hallen, was contracted to do the work. He arrived on the isthmus in 1906 and began using a large glass-plate camera to obtain the required print quality. When the canal was opened in August 1914, it was Hallen who recorded the first transits, although taking photographs of ships was not part of his normal work.

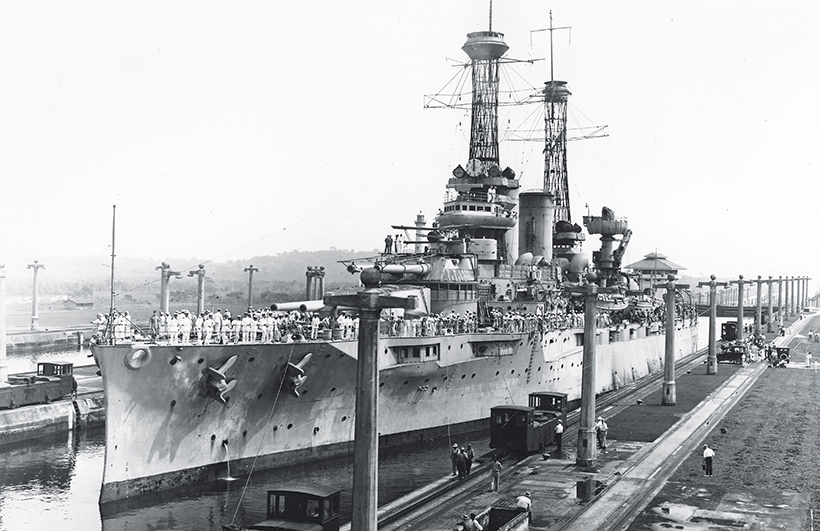

One of the few naval vessels photographed by Red Hallen that’s still afloat is the battleship Texas, which continues to serve as a floating monument at San Jacinto State Park near Houston, Texas. Hallen caught the ship at Gatun Locks in June 1919, as part of the large armada of US Navy vessels he had hastily returned to the isthmus to photograph. Noticeable in this view is a small aircraft perched on the vessel’s upper forward turret. The biplane had earlier been successfully flown off the turret by Lieutenant Commander Edward O McDonnell, thus bringing aviation to the US battle fleet.

Nevertheless, in 1919, when it was announced that a major portion of the US fleet would be moving through the canal from the Atlantic to the Pacific, Hallen, then on leave in the US, volunteered to record the event. When he could not find a commercial sailing available to return him to Panama, the Navy provided him with a berth on the destroyer USS Ward, a ship later to gain fame during the 1941 attack on Pearl Harbour.

Also transiting the canal in August 1919 were a number of US four-stack destroyers, including USS Badger (DD-126) and USS Schley (DD‑103). During World War II, Badger served largely as an escort vessel in the Atlantic and Caribbean but Schley, which was at Pearl Harbour when the Japanese attacked in 1941, went on to see action in the South Pacific after conversion to an attack transport (APD-14). The ship narrowly missed being hit by kamikazes that mortally struck her sistership, Ward (APD-16), in 1944. Both Schley and Badger survived hostilities, but were broken up for scrap only a few months after being decommissioned in 1945.

Favourite spots

Once Hallen arrived back on the isthmus, he immediately set out with his equipment to find the best vantage points for capturing the naval ships as they transited. The canal, running on a northwest-southeast axis though jungle-clad mountains and across two lakes, presented a number of difficulties, but Hallen soon identified the most promising locations.

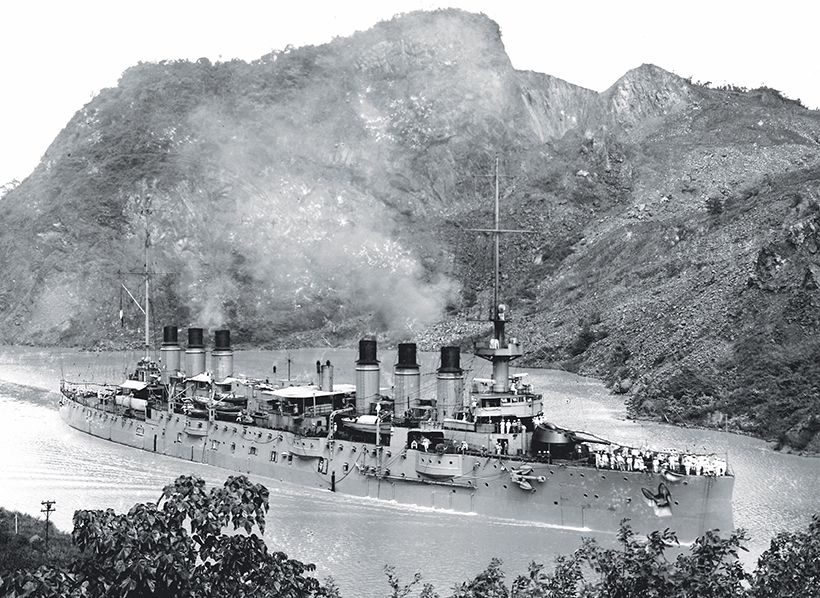

Considered the first of America’s dreadnought battleships, the 1908-built USS Michigan was photographed between Gold Hill and Contractor’s Hill on June 13th, 1920, while she was on a training voyage with her sistership, USS South Carolina. Both vessels mounted eight 12-inch guns, along with 22 3-inch guns and, in tropical weather, used serpent-like canvas ventilators to catch air for their crews below. The lattice-style masts were designed to limit damage by shell fire, but proved susceptible to corrosion and were removed from later ships. The circular dial on the forward mast indicated to other vessels in the battle line what Michigan’s target range was, while the target bearing itself was indicated by the degree marks on the turrets. A victim of the Washington Naval Treaty of 1922, the 16,257-ton displacement ship was broken-up in 1924.

The locks were natural sites because they provided close-up views of vessels as they remained almost motionless, and he seemed to have had a preference for Pedro Miguel Locks. This was quite possibly because of the Locks’ proximity to Gaillard Cut.

With a government car at his disposal, Hallen could easily photograph a ship from several vantage points in the Cut and then drive down to Pedro Miguel for close-up views as the ship was locked through. Pedro Miguel and the Miraflores Locks were also favourite spots for local photographers from Panama City, who came out to take pictures of the ships and their crews. Their results, often colourised for postcards, would be on sale to the sailors by the time their ships docked at Balboa.

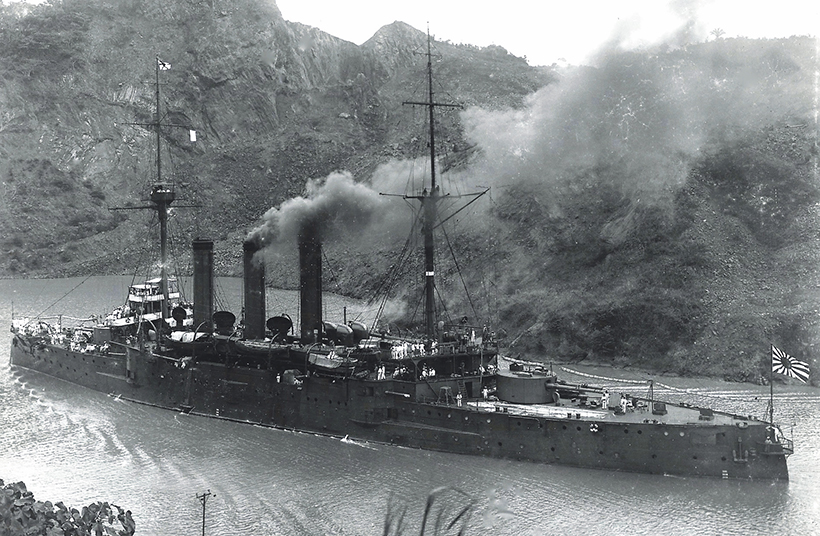

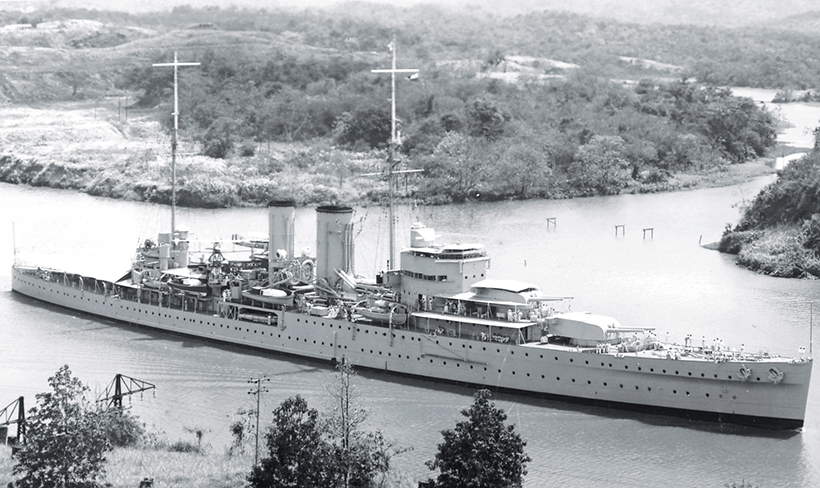

One of a number of obsolete Japanese naval ships that were sent through the canal between the two world wars on training voyages, the three-funnelled cruiser Iwate had been laid down by Britain’s Armstrong Whitworth in 1898, and was completed in 1901. The coal-burning ship took part in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-05, but played only a minor role in World War I. Thereafter, she was used mainly for training purposes and, towards the end of World War II, was sunk in shallow water by American aircraft and later scrapped at Kure.

Gaillard Cut

Gaillard Cut, now known as Culebra Cut, where the canal had been excavated through Panama’s continental divide, became a premier spot for taking views of ships as they steamed from one ocean to the other. Unless dredgers were present, the Cut was devoid of human activity and transiting vessels were alone.

Like several other navies, the US Navy often used obsolete warships as training ships and such was the case in 1922, when the elderly cruiser USS Olympia (CA-15) transited Gatun Locks in company with the battleship USS Florida (BB-30). Famous as the flagship of Commodore George Dewey at the Battle of Manila Bay during the Spanish-American War, Olympia was on her final training cruise. She survives as the oldest steel-hulled American warship still afloat, at Philadelphia. Florida, lead ship of her class, served in Europe during World War I and remained in service until 1930, when the London Naval Treaty dictated her demolition.

From the heights of Contractor’s Hill, panoramic views akin to aerial photography could be accomplished while the ships transited majestically below. The Hill’s main view-point was where Hallen chose to record some of the first large naval transits, often with dredgers in the background.

Many of Hallen’s prints, in fact, contain views of the Cucaracha Slide, one of the passage’s most notorious walls of moving earth. Even during the French period of excavation, this slow-moving mound of rubble caused problems and it continued to plague the canal well after construction was completed.

Of unique profile, and the only ship of her class, the French armoured cruiser Jeanne d’Arc was photographed in Gaillard Cut in late 1923 while making a goodwill visit to the isthmus in connection with the unveiling of a French monument at Panama City. Completed in 1903 by Arsenal de Toulon, the 11,445-ton displacement vessel made use of three, four-cylinder triple-expansion steam engines, each driving a single, three-bladed propeller, to achieve a speed of 21.7 knots on trials, 1.7 knots less than expected. Although involved in action during World War I, the ship was normally employed for cadet training and, when replaced by the newer 1911-built cruiser Edgar Quinet in 1933, she was sold for demolition in 1934.

Locks and cranes

Other locations along the waterway offered different perspectives of shipping, and Hallen managed to make use of almost all of them. At Gatun Locks, on the Atlantic side, a tall lighthouse provided a platform for elevated views of lock operation, something that was not available at the Pacific locks of Pedro Miguel and Miraflores.

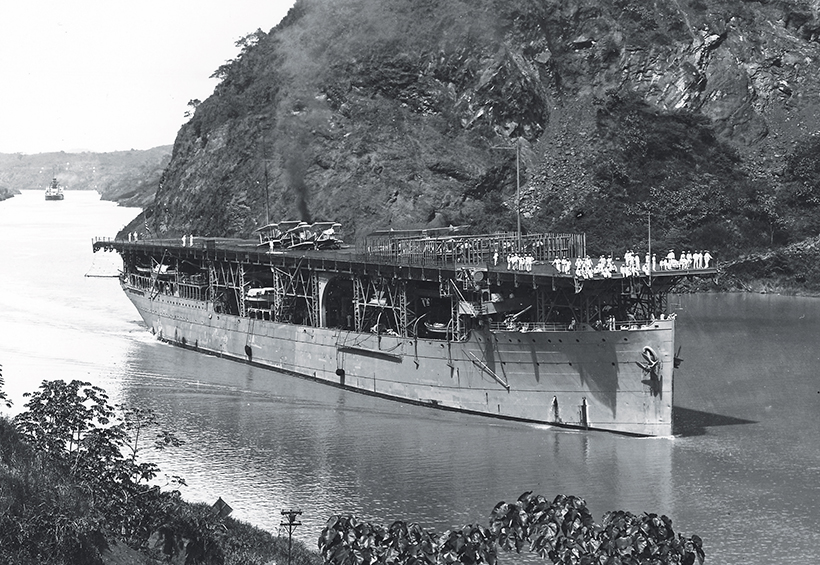

On November 16th, 1924, Hallen photographed America’s first aircraft carrier as the 12,700-ton displacement USS Langley transited from the Atlantic to the Pacific while heading for San Diego, California. Built as the collier USS Jupiter in 1912, the turbo-electric-powered ship, a first for the US Navy, was converted into an aircraft carrier by the Norfolk Naval Shipyard in 1920. The vessel was then used to train pilots for the Navy’s next two aircraft carriers, Saratoga and Lexington, before being converted into a seaplane tender in 1936. It was in this configuration that the 30-year-old ship was destroyed by Japanese aircraft on 27th February, 1942, while she was carrying a deck load of 32 P-40 fighters to the Dutch East Indies.

At the settlement of Gamboa, a short drive from Pedro Miguel, Hallen would climb up the booms of giant floating cranes to capture passing ships, the resulting view looking similar to that from a low-flying aircraft. Another location used to advantage because of its height was the signal station near Gamboa, where the Panama Railroad ran along the canal’s edge.

A photographer from Panama City positions his glass frame camera to capture crew members aboard the 1904-built German light cruiser Hamburg, as the warship transits Miraflores Locks in April 1926 while on a training voyage. Hallen took this view from the lock’s control tower, and also managed to capture one of the canal’s six rotatable emergency dams in the background. These could be rotated across the lock entrance to drop metal shutters that would block any loss of water.

Retirement

After Red Hallen retired and left the isthmus in 1936, his camera was handed over to his assistant, Manuel Smith, who continued to use glass-plate exposures until late 1939, when most photography became restricted. By the time plastic-film came into official use at the canal during World War II, over 16,000 glass-plate negatives had been exposed, some dating all the way back to a small collection left by the French in the late 1800s.

On 7th February, 1928, the Panama Canal was introduced to the size of the modern aircraft carrier as the 43,055-ton USS Saratoga transited two weeks ahead of her sister, USS Lexington. Completed in 1927 from a hull originally designed for a battlecruiser, Saratoga carried four twin eight-inch gun turrets before and aft the island. After surviving numerous combat operations during World War II, the pioneering ship was sunk during atom bomb tests off Bikini Atoll, in 1946.

However, once the required photographs had been printed, most of the plates were stacked away and forgotten. They were rediscovered by chance in the mid-1960s, after which they were cleaned and sorted, then shipped off to the US National Archives in Washington DC. Although of excellent quality, only a few hundred contain views of ships, but these offer a rewarding glimpse back through the years when the world’s navies were the great strategic weapons of the era.

Like America’s Houston, the Royal Navy’s heavy cruiser Exeter would be lost off Java in early 1942. Hallen managed to capture the ship from the Gamboa signal station on 8th March, 1935, as the cruiser was returning to Bermuda from a goodwill trip along the west coast of South America. A scaled-down version of the Country class cruisers, the York class Exeter carried six 8-inch guns and these were put into play several years later when the 8,390-ton ship took part in action against the German pocket-battleship Admiral Graf Spee off the River Plate. The British cruiser was sunk on 1st March, 1942, by Japanese torpedoes off Bawean Island.

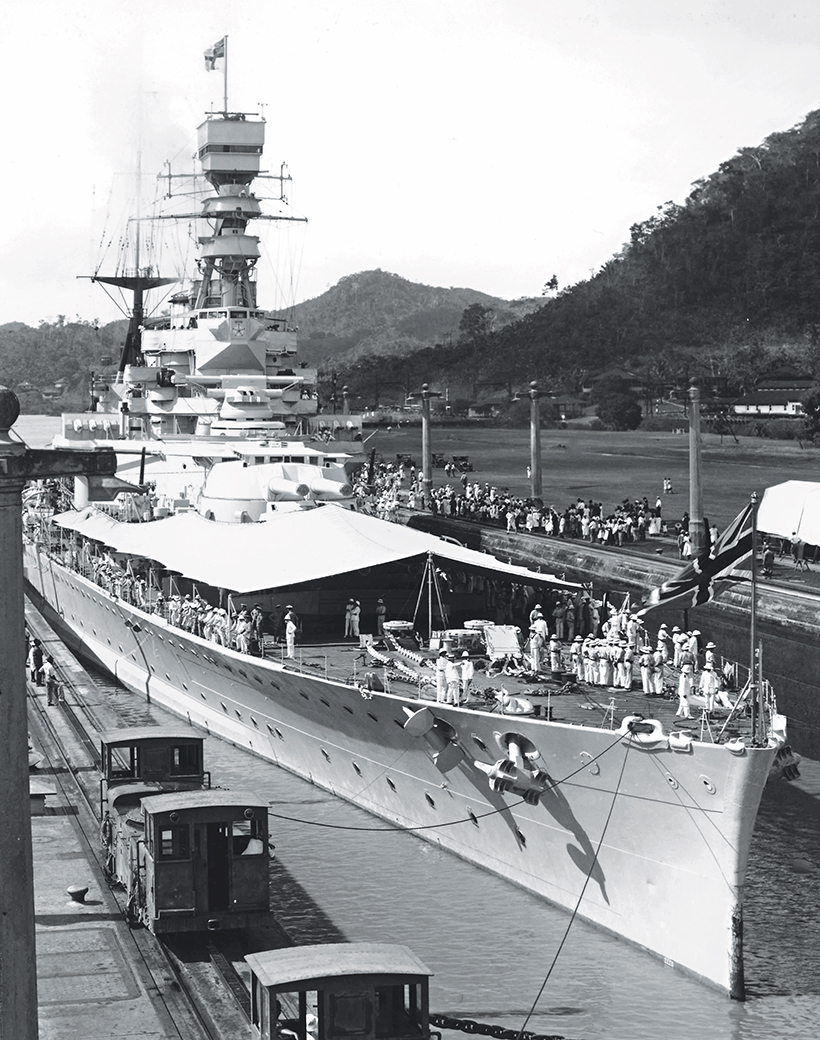

Rigged for tropical weather, the Royal Navy’s HMS Renown pauses in Pedro Miguel locks on 25th January, 1927, during a voyage from the UK to Australia and New Zealand, with the Duke and Duchess of York on board. Completed by Fairfield at Govan in 1916, the British battlecruiser had undergone reconstruction several years earlier, which had added significant armour plate to the hull, increasing her beam measurement from 91.6ft to 103ft and her loaded displacement to 36,600 tons. After surviving extensive campaigns in the Atlantic and Indian Oceans during World War II, Renown was placed in the reserve at war’s end, and sold for scrap at Faslane in 1948.

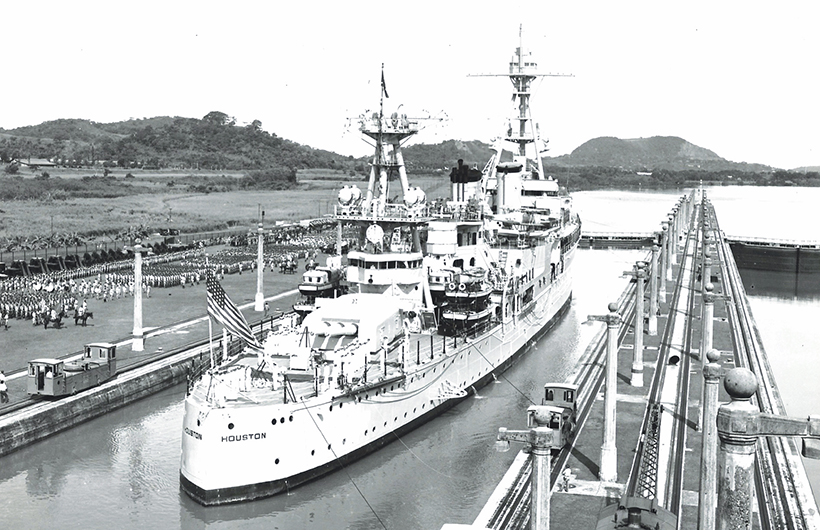

To be lost early in the war, the American heavy cruiser Houston pauses in Miraflores Locks on 11th July, 1934, while military honours are rendered shoreside for President Franklin Roosevelt, then aboard along with Assistant Secretary of the Navy, Henry L Roosevelt. Both men had embarked at Annapolis, Maryland, for an extended cruise through the Caribbean and on to Portland, Oregon, via the Hawaiian Islands. Commissioned in 1930, Houston was to make her final transit of the canal in

1939, after which she was posted to the US Navy’s Asiatic Fleet, only to be lost in the Battle of Java Sea during 1942.

For a money-saving subscription to Ships Monthly magazine, simply click here