Classic mobile catering vehicles

Posted by Chris Graham on 18th October 2021

Peter Esposito looks at the foreign vans in use as classic mobile catering vehicles, together with some indigenous types.

Classic mobile catering vehicles: Seen in the grounds of Leeds Castle, Kent, recently, a pre-1964 Citroen ‘H’ van, with two-piece windscreen. This model isn’t particularly rare, as they had been in production for 17 years by then.

I’d like to add a few thoughts about the very interesting article about mobile catering vehicles that appeared in the May 2020 issue, which posed the question; why aren’t there more British vans represented in their ranks, compared with mainly the Citroen ’H’ and, to a lesser extent, the Peugeot ‘J’? May I suggest one reason for this is the sheer number of ‘H’-types built, compared with home-produced vehicles.

From 1947, until the last one rolled off the production line in 1981, a total of 475,000 ‘H’ vans were built in France and Belgium, together with small numbers in the UK, at Slough, where Citroen had an assembly facility. Comparable UK vans with similar carrying capacity of 20/25 cwt – the Morris PV and Austin K8 – could only muster totals of 16,000 and 26,500, respectively, albeit over a shorter time scale. But this was mainly due to their un-competitiveness on the open market.

A short-wheelbase model, showing the higher counter bodywork and the practical top-hinged flaps, providing weather protection, which was proving very useful on this occasion.

The lovely, cute Morris ‘J’, which also appeared at the same time as its UK counterparts could, itself, only manage 48,000 and it was just too small to be considered in this group. Try standing up in a ‘J’! The PV, (Parcel Van), was considered an advanced design at its time of introduction, with forward control, OHV four-cylinder engine, four-speed ‘box and hydraulically-operated brakes on all wheels.

However, after just 52 had hit the road, World War II stopped all non-essential vehicle manufacturing, and the Nuffield organisation went over to war production. With hostilities over, PV production recommenced but, by 1946, the once cutting-edge design of the late 1930s was showing its age, with an ash-framed body, aluminium sheeting and a canvas roof. It soldiered on until 1953 when the newly-formed BMC withdrew it from the market.

Another split screen model, showing the longer mobile version, seen appearing at a local event in Kent.

The other UK contender, the Austin K8, (Three-way Van), was of a more modern design, making its debut in 1947. It too was of a forward control layout, with a high driving position giving a commanding view ahead, hydraulic brakes on all wheels and a 2,199cc OHV petrol engine, which could easily be removed for overhaul.

Horses for courses: Seen in its native environment, a ‘proper’ shop as opposed to a ‘retro’ conversion. A market square in Belgium during the 1980s – notice that it’s forming a nice little group of ‘like-minded’ vehicles.

Its design brief was for a superior, nimble urban delivery van, at which it excelled with its compact, 7ft 9in wheelbase, wide driver’s door, wind down windows and the extra kerb-side doors that facilitated safe transfer of loads. Roller shutters were an optional extra. I always thought this was a good-looking vehicle and the nearest to a French van outline – perhaps a Peugeot?

A Citroen showing the flag – trying to change its spots? Seen at Walmer Green, Deal.

However, both these sound UK designs had a major drawback, in that headroom was compromised, because of their conventional construction utilising a high chassis frame. This wasn’t considered a problem at the time, as these vans were only designed for local delivery work. Even their successor, the excellent LD built from 1954-1967, still had the limited headroom of just over 5ft, making a working environment difficult as a mobile, unless fitted with specialised bodywork.

Also seen at Walmer, a Volkswagen Transporter T2 sporting a very clever conversion, possibly on a UK van.

This is where Citroen scored over the opposition, by using well-tried components from its successful ‘Traction Avant’ car. The ‘H’-type specification was light years ahead of UK products. It was the first mass-produced, front-wheel-drive van, combining chassis-less construction with a monocoque body made from corrugated sheeting which required only simple pressing tools; an idea first used pre-war by the German Junkers aircraft company.

Even the French go for something pre-‘H’, most likely a pre-war Renault with that bonnet? Photographed in the late 1980s.

Without the need for a cumbersome and heavy chassis, the van was light and easily adaptable, notably for extending the wheelbase and body without major redesign and, therefore, was cheaper to achieve. With its four-wheel independent suspension, rack and pinion steering, readily available spare parts and ease of maintenance, this made it a success from the start. Devoid of any unnecessary curvature, the square, angular bodywork gave both maximum internal volume and great strength to the floor, (supposedly able to carry a horse – alive, or perhaps in handily-size joints?).

Another clever conversion of an earlier VW van, seen at Kings Cross Coal Drop, attending a classic car event.

The independent suspension acting on the wheels, which were placed on the extremities of the body, gave a very smooth ride over both tarmac and rough farm tracks. The chassis-less construction and front-wheel-drive ensured an extremely low floor, ease of access from the rear via a small step, through two, low side-hinged doors, plus a top-hung one that also acted as a shelter against the weather while loading.

Also at Kings Cross, the other contender for a French classic mobile, a Peugeot ‘J’ Type.

This formula proved so successful that, other than various mechanical ‘tweaks’ through the years, the bodywork was virtually left untouched, with only the most obvious change; the twin front screen being replaced by a single glass, in 1964.

It can be done! A very nice conversion of a late Austin-badged LD, seen at Kings Cross last year. Was this possibly a former ambulance?

The design department knew what was needed from the start. Citroen chose three model types from the beginning; a standard panel body, a pick-up and a special purpose, which catered for mainly what we would refer to as ‘mobiles’.

A wonderful conversion of a PV at a Goodwood Revival Meeting. A former West Riding County Ambulance (complete with bell), carrying an Appleyard body, dating from 1953. A great survivor!

The majority of the French resided in urban conurbations, but there was also a significant rural population, spread thinly around an area some two-and-a-half times the size of the UK. It seems that because of the distances involved between communities, there was a sound economic reason why market mobiles did their rounds, offering a wider choice of their wares that a small static local market could not.

A high-roof LD conversion, but lacking the ‘finesse’ and practicality of the ‘H’. Seen at a very wet Goodwood Revival Meeting, this was selling programmes, but closed up shop when the heavens opened!

Conversely, in the UK, the small numbers of mobiles reflected the high cost involved in converting standard panel vans by bespoke coachbuilders or, if available, converting an old bus for the purpose. Even then, these mobiles usually only worked singly on new housing estates, until more permanent shops were built, so mobiles were only seen as a stop-gap.

A Commer BF high-top conversion dishing out hot dogs and burgers to cold spectators, also at Goodwood.

We tended to prefer the jolly butcher, baker and milkman dressed in their striped aprons, whistling merrily and delivering to our front doors – could the British weather have played a part in this? For this type of service, a small standard van, the Morris ‘J’, Bedford ‘CA’ or perhaps a wheezing, archaic Fordson E83W fitted out for carrying trays would do nicely; no need for anything bigger and more expensive.

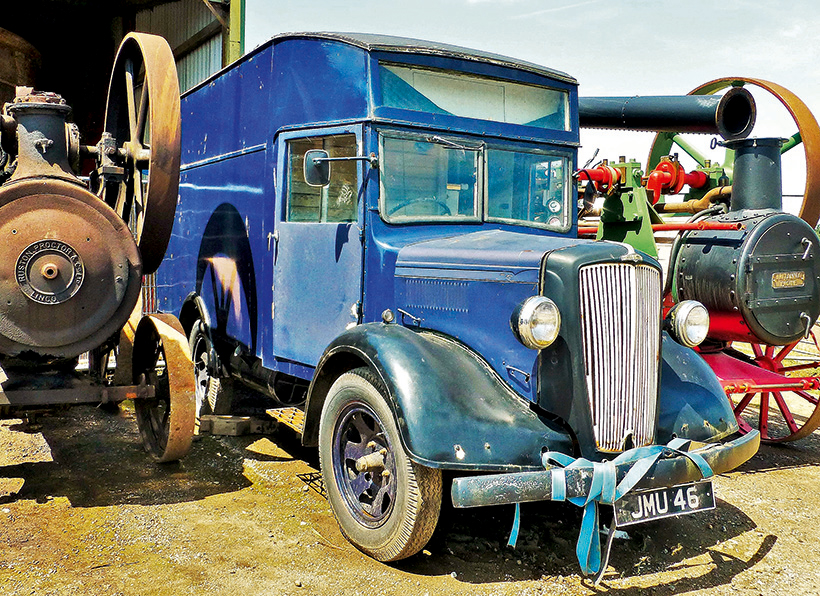

Another candidate for conversion? An LC waiting in the wings at Preston, Kent.

Put simply, the French had the culture of mobile markets well before World War II, and the ‘H’-type was just a continuation on a theme, leading to the great number of suitable vans which are available today, albeit in diminishing numbers – hence the need for ‘retro’ plastic models to satisfy demand, as reported in the May issue.

Seen at the much-missed Preston Steam Fair, in Kent, a lovely conversion of a Morris-Commercial LC, doing a very brisk trade during an extremely hot weekend.

I’ve always enjoyed walking through a rural French marketplace over the years, taking in not only the wonderful aromas of the foods on offer, but the sheer style of the vans plying their trade. Long may they live on.

You can stand up in a ‘J’, but only after a bit of work! This high-roof version was seen at South Bank, in London.

An early, split-screen Bedford CA, making a living at Kings Cross Coal Drop.

Small it may be, but perfectly formed. A Fordson with a bit of style at the first Goodwood Meet, in 1998, 50 years on from opening as a race track.

A newer Bedford CAL, proving a hit with hungry crowds at Preston Steam Fair, in Kent.

A Commer PB, 1500, Spacevan, or whatever you want to call it, trading at Kings Cross, next to the Regents Canal, during a classic car show.

Don’t forget the big boys! Former Routemaster RML type, not only selling food and drink, but also doubling up as the PA centre at Kings Cross.

I realise its ‘only’ an ice cream vending van, but what bodywork on this Bedford CAL, which I believe is a stylish ‘Morrison-Electofreeze’ conversion, seen at Leeds Castle, in Kent.

They don’t get much smaller! A ‘Stop Me and Buy One’, pedal-power, seen at Brooklands Motor Circuit.

They don’t come much larger! Apparently, this is a 1947 Diamond T 509 tractor unit, with a mobile bar and burger bar trailer, seen at the Goodwood Revival Meeting.

Another ice cream vending van, but a great historical survivor, still plying its trade. One of the very few remaining Karrier BF ‘mobiles’ dating from when the soft ice cream revolution hit the streets in the hot summer of 1959.

For a money-saving subscription to Vintage Roadscene magazine, simply click here