The fascinating road/rail story

Posted by Chris Graham on 27th January 2020

Malcolm Bates discovers a fascinating batch of photos from the archives, depicting the UK commercial vehicle industry’s road/rail story

Now fair enough, there isn’t a lorry, or a ‘motor omnibus’ to be seen in this otherwise wonderful view of the outside Euston station, taken before the FA Cup Final at Wembley, in 1923, if the poster in the background is to be believed. The match between Bolton Wanderers and West Ham United was famous for attracting an estimated crowd of over 300,000 – although the official capacity of the stadium was only around 126,000. The exact reason behind why this image was taken by the official photographer working for the LMS publicity department (so we now know it was taken after 1923), isn’t known, as the famous Doric Arch (built in 1837 to herald the arrival of this new form of transport in the capital) at the entrance to the station was hardly in vogue, or ‘moderne’ by the time this photograph was taken. In fact, it was considered easy prey for demolition from the mid-1930s onwards, judging by plans for ‘A New Euston’ drawn up by the LMS in 1938, but never started because of – we assume – the outbreak of war. There was, in fact, an outcry from conservationists, the suggestion at that time being that it be moved, rather than demolished. Of course, the architects finally got their way in the 1960s, and all that remains of Philip Hardwick’s masterpiece today are the small side ‘lodges’ and ‘The Arch’ name, which now refers to some tacky, modern pub nearby

The Stevens-Stratten Archive includes numerous references to ‘railways’, which helps remind us that, for many years, it was considered good practice to ‘co-ordinate’ services between each mode, to reduce wasteful dead running and undue duplication of services. In other words, the exact opposite to the reality that is Britain today, where our bus services (if we still have any) no longer mesh with train arrivals and departures.

But there has also long been a notion that road vehicle engineering might benefit rail operation while, in other cases, road vehicles have been built specifically for the transport of new railway locomotives or rolling stock for export. We’re probably all familiar with the story of the Scammell Scarab and its predecessor, the ‘Mechanical Horse,’ but there’s more to this story than that…

It’s always the same, isn’t it? When you’re looking for something you can never find it. I’m not sure what the limitations of that statement might be but, in my case, it could cover looking for another car, job, house or partner. I might be on dangerous ground with that last one, but the universal rule seems to be, the harder you look, the less likely you are to find what you’re looking for. That certainly applies to lost car keys, but it also seems to apply to archive photographs!

The other day, I was searching my files for certain types of lorry bodywork to illustrate a Vintage Roadscene feature. Except the economics of producing an article for your enjoyment meant that I could afford, at most, a couple of hours to find what I was looking for, write the article and caption all the photographs with something entertaining and meaningful.

The latter isn’t so easy when the caption slip has been torn from the reverse by some over-jealous block-maker 60 years ago… Nope, I’m still half a dozen pictures short, without using something that we’ve already seen before, which is against the whole ‘mission’ of Vintage Roadscene.

But here’s a funny thing; while you’re looking for one thing, there seems to be some unwritten rule that you’ll find loads of other things that you weren’t originally looking for, but which are – none-the-less – interesting. And that’s what we seem to have here…

The subject that I was originally planning to cover was that of ‘Municipal vehicles’. Partly on the basis that it’s a subject that’s close to my heart, but also because I’d recently spent far too much money buying the remains of an archive from a well-known, but recently deceased enthusiast, at auction. I got a selection of municipal catalogues and photographs because, I suspect, the only other person bidding was Mr ‘Off the Wall’.

But, while I was sorting that out, several pictures of road vehicles with a railway connection appeared out of the woodwork. Not so much a whole batch of railway delivery vehicles – more of that another time, perhaps – but more a random selection of unusual, or oddball road-rail related pictures.

So, let’s have a closer look…

Staying with the LMS, this photograph thankfully does still have part of its original caption in place. This informs us that the location was the ‘Hackney Electrical Works’, showing ‘a Motor Lorry’ unloading what seems to be LMS ‘H Type Containers’. Three such containers were carried on a full drawbar trailer pulled by what looks to be a Beardmore tractor unit with ‘Multiwheeler’ load transfer coupling device. Fitted with a canvas-roofed cab and still using oil lamps (rather than electric side lamps), it must have been fun driving the thing at night. Note that at least four other containers were stacked-up behind the trailer, and the portable compressor to power jack-hammers is visible in the left foreground. Aside from the ‘sheer legs’, there doesn’t appear to have been any other material handling kit present, so chances are, quite a lot of hard labour was involved. Finally, we can just spot a legacy of the Victorian era by the radiator of the tractor unit, and the smartly-dressed site foreman, complete with bowler hat!

Here’s another photograph from the LMS publicity department files. It shows, we are informed, the ‘Spondon Container Terminal’ (or the word could be ‘facility’, it’s hard to read), showing what looks like a Sentinel steam lorry in the middle distance. It looks like they were in the process of transferring one of the loaded rail wagon ‘containers’ over on to the lorry chassis. As most British railway wagons didn’t even feature coupled brakes at the time, we have to assume that any winch or hydraulic power was provided by the lorry chassis, as there’s no other plant, or machinery visible. Although the wagon on the far right is of conventional design, it also carries the legend, ‘use for steam coal’. Odd, as the containers themselves appear to have been loaded with ballast. But if it wasn’t for permanent way ballasting (if so, why would it be transferred to a road vehicle?), what was it to be used for? A possible answer; the bulk load of crushed stone was being shipped from the nearest railhead for use in construction of a new by-pass, perhaps?

Here’s a more conventional method of transferring materials from rail to road – gravity! This satisfies the time-honoured British approach of never doing things properly, if you can save a few quid by doing it almost as well, (the British management mantra that would finally run-out of credibility during the design process of the Morris Marina). In this case, we see a rather down-at-heel ‘private owner’ rail wagon operated by Tarmac on the loading staithe, where material was being transferred into a pair of smart, new Armstrong Saurer tippers. The shape of the loading hoppers suggests that they were designed for some form of ‘bottom-dump’ wagons, so we can assume that the large handle on the side of the wagon was used to manually open the bottom ‘doors’ for discharge. The location was the Tarmac works in Ettingshall, Staffs., and the photograph was taken on January 5th, 1935

We need to er, ‘back track’ a couple of years here, to 1932, and this wonderful image of an AEC Regal, single-deck bus converted to a… Well, it wasn’t actually a ‘road railer’ was it because, clearly, there was no obvious provision of road wheels? So, in effect, it was an AEC ‘rail bus’. The absence of the ‘Oil Engine’ script on the radiator suggests that it still had a petrol engine, but here’s the interesting thing; although this photograph came from the AEC factory archives, it’s a ‘modern’, post-Leyland take-over print from the 1970s. The destination indicator panel above the cab features the ‘Regal’ model name script, which suggests this was an official product marketed by AEC, rather than a third-party modification.

The first Regals emerged in 1929, and the other significant new ‘factory’ product at the time was the Karrier ‘Road Railer’. So, does this suggest that the commercial vehicle industry generally saw the potential for modified road vehicles being used by the railway companies to reduce the cost of rural branch lines in a period of economic depression? If so, they were sadly wrong, but the caption on the back poses more questions such as, where was this Regal ‘rail bus’ being demonstrated? One answer seems to be ‘on the LNER line at Castleford’, as suggested in the pencil-scrawled caption on the reverse of the print. But, in brackets, there are the words ‘Guernsey Light Railway’ and ‘Isle of Wight, Regal.’ So, which was it? Or was it demonstrated to all three? Oddly, unlike the Karrier ‘Road Railer’ – which was the subject of several press events at the time, and was considered worthy of a comprehensive sales brochure – very little publicity seems to have come out of this venture, from AEC. This is ironic considering that it was AEC that went on to supply rail-cars to various railway companies over the following decades, not Karrier…

Here is the front cover of the amazing Karrier ‘Road Railer’ brochure. I mean ‘amazing’ in that, while designed by Karrier in 1930/31, when still an independent company based in Huddersfield, this brochure was actually produced in 1936, after Karrier had become a brand within the Rootes Group, and the whole operation had been transferred to Luton.

While the Luton factory was located alongside the Midland Railway main line from Bedford to St Pancras, there are no photos of it on the tracks at that location, although it’s possible that one shot used inside might have been taken in the former London to Birmingham works yard, at Wolverton, near Bletchley. This would have probably been the nearest LMS facility with a carriage works and paint shop. Does that suggest that ‘The Carriage Works’ built the body? But while the suggestion was that the Karrier Road Railer was built ‘in co-operation’ with the LMS, how come no more were ordered? Calculations regarding unladen weight and complexity would have been obvious from day one, so that can’t have been the reason. And, if it was just down to cost, even with a petrol engine, it must have still been cheaper to build and operate than a steam locomotive and several carriages. Perhaps it was that well-known Achille’s heel of rail buses; poor ride quality?

Inside the Karrier ‘Road Railer’ brochure, the centre spread gives us the whole nine yards. It’s not so much a brochure, more a detailed treatise! Reading the copy helps us understand where the original design brief went a… well, a touch ‘off the rails’, in that the whole concept seems to have been designed around the assumption that the Karrier Road Railer would be operated on a railway built to the British Standard Gauge which, as every schoolboy knows, is 4ft 8½ins. The problem with that? Well, while Britain invented the modern railway, not everyone in the world was as clever as your average British schoolboy.

Indeed, in many parts of the world, where perhaps a Road Railer would have been the ideal tool for lightly-loaded rural lines, the gauge might be anything from 3ft (or one metre in the case of foreigners who insist on being difficult), up to 3ft 6ins. This applied in South America, Africa, some Indian hill railways and those in Australia and New Zealand. All of which might well have been potential markets for this versatile British product. The problem? A narrower gauge just wouldn’t enable rail wheels to slot into the chassis without a major redesign.

In Great Britain, there may have been another element at play – ‘NIHS’, the dreaded ‘Not Invented Here Syndrome’. Railway companies were used to designing and building all the kit they needed, from entire steam locomotives to lorry bodies and cabs in many cases. So, even if someone in the motor trade came up with a really good idea, the chances were that it would be shot down in flames, thanks to NIHS. So, was this the ultimate reason that the Road Railer project failed? It certainly wasn’t through the want of trying on the part of Karrier.

But, while the Karrier brand was soon demoted to that of ‘municipal and works transport specialist’ under Rootes control after 1934, the Road Railer continued to be marketed for at least another couple of years after Rootes took control – presumably in an effort to make a return on what must have been a significant investment, in design terms. But it was all to no avail. The prototype bus, with unique dual-sided, mid-entrance bodywork (to enable passengers to alight on to a platform on either side of the vehicle when in ‘rail mode’), stayed ‘unique’, although a further, normal-control, 26-seater built to a slightly different design, was supplied to Rotterdam Tramways.

While the prototype, 26-seater bus had the initials ‘LMS’ emblazoned down the sides, and was tried on various branch lines (including the Stratford-on-Avon Joint that ran from the former Midland main line to St Pancras at Ravenswood Junction, westwards to Broom on the also former Midland line from Gloucester near Alcester), there was also at least one lorry version, which was operated in the North of Scotland on the West Highland Line, by the rival LNER.

Described in the brochure as ‘a freighter for track maintenance purposes’, it was a two-axle, forward-control chassis with a dropside body and, seemingly, would have been even more useful than a passenger-carrying bus, as it could take crews and materials by the shortest (or fastest) route by road, then transfer to the rails at the nearest level crossing or goods siding to where the track work was located. If there was a problem with the design – other than complexity and cost, that is – it had to be weight. The specification for the LMS bus gives the unladen weight as 7 tons 2 cwt when fitted with a 37hp, six-cylinder engine, which surely suggests the ‘top speed’ of 60mph in road-going form was a bit optimistic for a vehicle that would have weighed about 10 tons when loaded with passengers

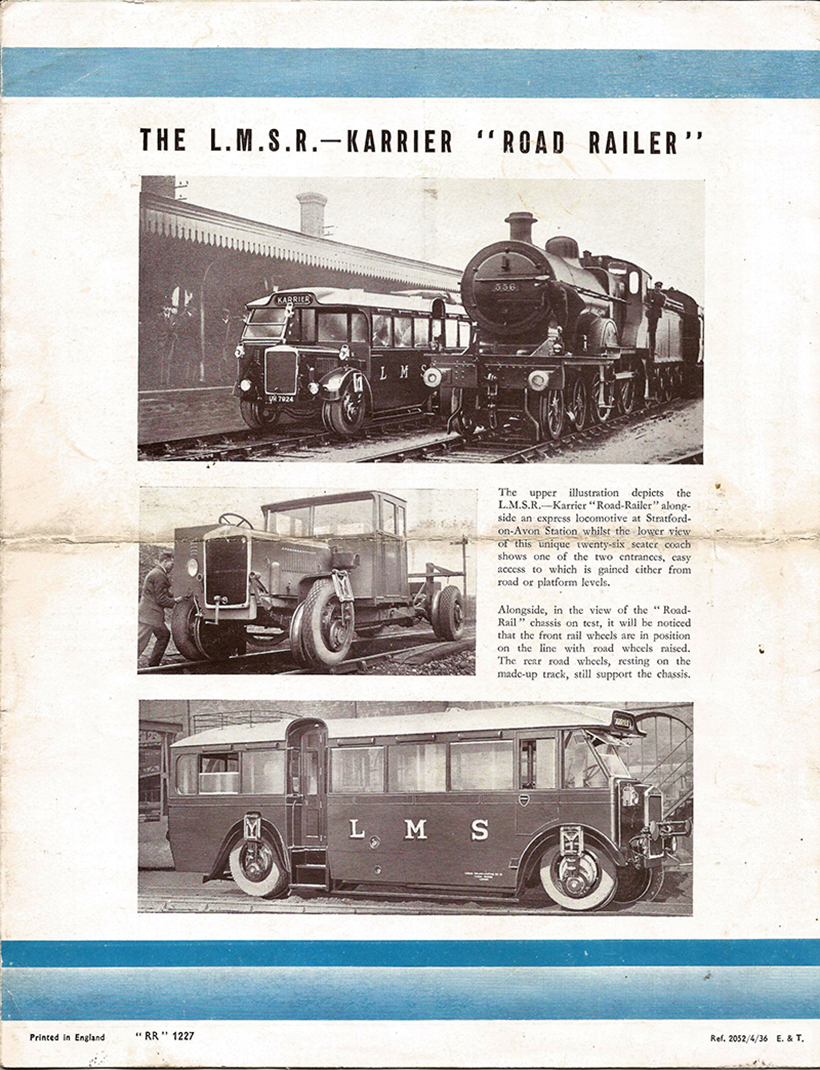

On the back page of the brochure (published in April 1936), we find a specially-posed photograph of the Road Railer ‘on the wrong road’ at Redbourne station, on the Harpenden to Hemel Hempstead branch, together with what’s claimed to be ‘an express locomotive’. It might well have been one in Midland Railway days before 1923, but 3P class 4-4-0 number 556 would have been well down the pecking order by the 1930s.

The Karrier Road Railer was the subject of several press releases, and appeared in a number of books and magazine articles at the time. The suggestion was that it would be used to ferry well-to-do passengers direct from the nearest LMS station, to the Welcome Hotel in Stratford-on-Avon, which was (and indeed, still is), located some distance out of town. What’s not explained, though, is how long all that took, and how frequently the service ran. But hang on, what did the passengers do in the meantime, while the road-to-rail process (or vice-versa) took place? Were they allowed to stay on board, and what happened to all their luggage, as they would surely have a lot of it for a stay in a posh hotel in Stratford-on-Avon? And up to 26 passengers suggests quite a pile of it.

Yet there was nowhere on the bus-type body for luggage, except an exposed roof rack, as the brochure has already informed us that the front rail buffers needed to be removed and stowed in ‘a special compartment arranged in the chassis’, together with the rail lamps and tools needed for the transfer process to be effected. The rear buffers were fixed to the chassis, and it was suggested that there was a rear coupling for towing a ‘trailer’, although no photographs show this. What looks like another ‘freighter’ chassis featured in the brochure was, in fact, the prototype bus on test. It was fitted with a mid-mounted ‘saloon’ (which looks like a lorry cab), to allow railway management to ride in comfort while testing the claimed 75mph speed potential, without losing their hats!

This is one of the best views of the interesting Karrier Road Railer, as it shows it taking on what looks like a full load of passengers. The road-registered ‘UR 7924’ (a Hertfordshire registration, like many LMS road vehicles), Karrier Road Railer is seen about to set off for a journey to Blisworth, where a connection could be made with mainline trains on the former LNWR line from London to Rugby. Oddly in this shot, the front buffer beam hadn’t been attached, although the rail lamps had. The sales brochure suggested that the road-to-rail transfer operation could be undertaken within a few minutes but, again, we weren’t told what happened to the passengers while this was going on. But who wouldn’t want to be one of the school children in the photograph, being given a chance to see the process first-hand, eh?

The clue really was in the name. Without doubt, it was the rising cost of keeping horses and finding staff to look after them 24/7, which was ‘the driving force’ behind the development of the ‘Mechanical Horse’. But while that phrase makes it sound easy, the truth is, a horse is a remarkably clever and adaptable animal, being powerful, available as standard with automatic torque-proportional gear-less transmission, and power steering allowing it to turn within little more than its own length. True, ‘articulation’ was already a feature of the road transport scene, but the concept of a rapid exchange of trailers, enabling one ‘tractor unit’ to operate with several trailers throughout the shift was very much an operational advantage first spotted by the railway companies.

Having swiftly come to the conclusion that an internal combustion-engined ‘tug’ could operate much faster than a horse, the lack of brakes on existing Railway-owned horse drays (or ‘lurries’), soon dictated that purpose-built semi-trailers were required. But here’s where it got a bit complicated. Scammell had taken over the Napier prototype in 1933 and, as a manufacturer of heavy-duty trailers, worked on its own ‘automatic’ coupling. Karrier, meanwhile, kept true to the original concept that had the tractor axle slotting inside the road wheels of the trailer although, on purpose-built trailers, these became the trailer landing legs.

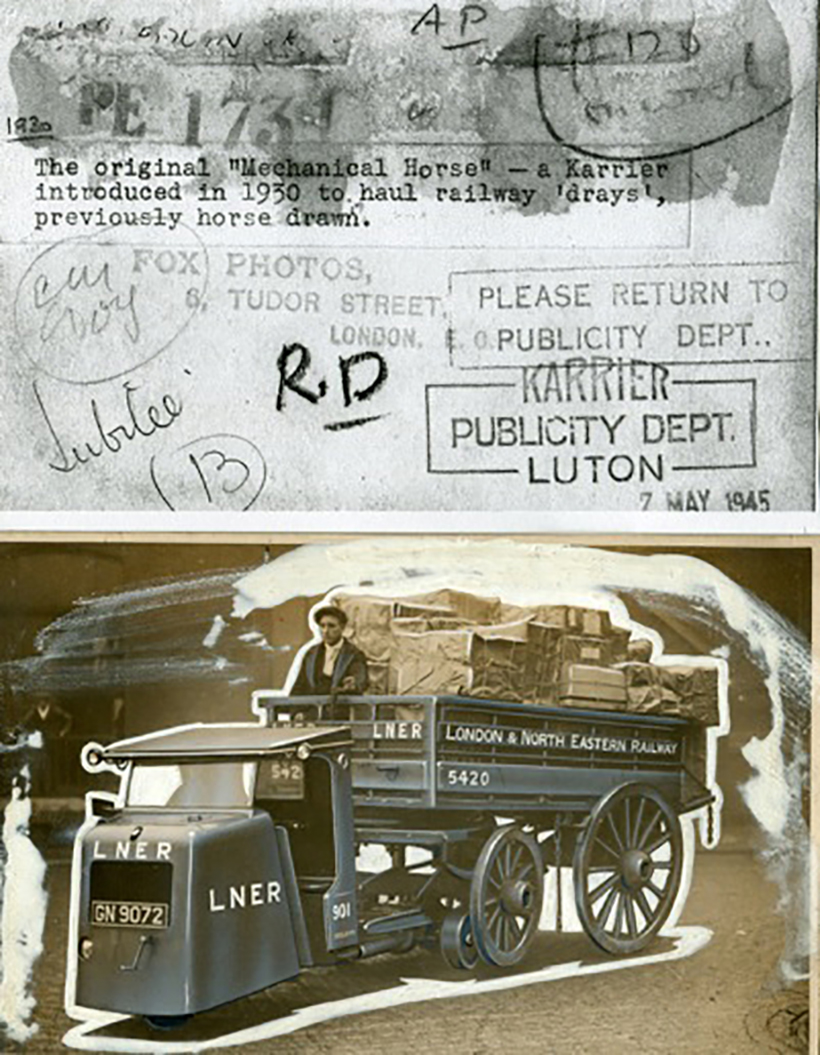

The downside was that the narrow track of the tractor unit must have caused stability issues, let alone braking concerns with heavily-laden trailers! The caption on this press release photo tells us that this was ‘the original Mechanical Horse’. It was used as part of a Karrier press release in 1930, and clearly shows how the rear-axle was designed to slot under the turntable of a horse-drawn wagon. The location of the ‘van boy’ up in the actual wagon itself was not a feature that would stand the test of time!

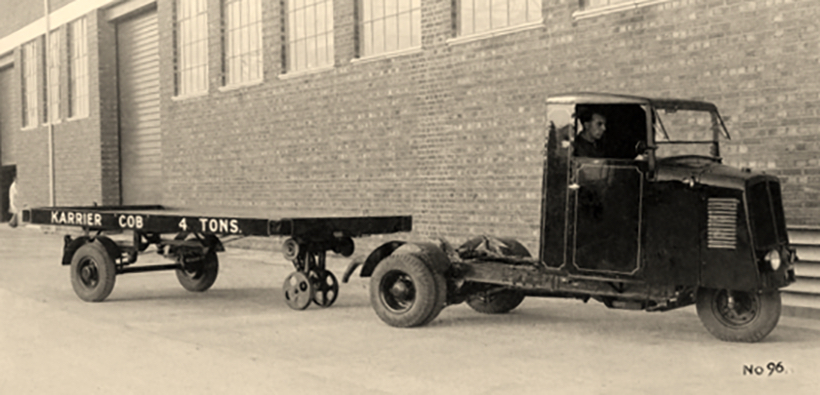

The Karrier ‘Mechanical Horse’ grew-up to become the Karrier ‘Cob’, and the original narrow axle and coupling gave way to the adoption of the rival Scammell automatic coupling system, as seen here on the newly-announced ‘4 ton’ model, with twin rear wheels posed outside the Commer factory at Biscot Road, in Luton. Directly behind the photographer was the former Midland Railway main line from Bedford down to St Pancras. A single headlight and ‘half’ cab doors with no window glass, might sound rather austere but, compared with sitting up on an exposed, horse-drawn cart seat with little more than an old sack for protection against the weather, it was bliss!

Here’s how the Germans did it. Or to be more accurate, the Austrians. This photograph shows an Austrian Railways freight wagon being transferred to a road-going trailer on which rail tracks have been incorporated into the load deck. There are at least 16 wheels, with the four centre axles on twins and the rears steering. It was designed to take goods directly to a factory when there was no rail siding connection. The ‘transfer’ process looks simple enough, but it did rely on the tractor unit being able to winch the rail wagon on to the trailer and, of course, to be able to lower it slowly off the trailer at the other end. Like the Karrier, it was all technically possible, but time-consuming. And, considering that a special tractor unit and trailer were needed, expensive, too

This is the Irish solution to the rising cost of rail operations in the face of reduced demand – scrap the trains and run lorries and buses instead! This motley collection of Ford and Austin lorries was photographed in 1951, at a time when the County Donegal Railways Joint Committee was still running passenger and goods services from Londonderry, to some of the most rural parts in the north of Ireland, over 120 route miles, including remote Atlantic coast settlements that were across the border in The Irish Free State.

The three ‘Fordsons’ (the middle one being a direct US/Canadian import) seen here were all powered by Ford’s side-valve V8 petrol engine, while the two new Austins featured tipper bodies. But, while the CDRJC tried various ways to cut operating costs, including the provision of Gardner-powered railcars – of which at least two have survived in preservation – its narrow-gauge neighbour with a terminal station on the other side of the River Foyle at Londonderry (the Londonderry & Lough Swilly Railway), gave up running trains completely in 1953, switching over entirely to buses and lorries, operating some 59 lorries and 52 buses in the early 1950s, together with some purpose-built mail vans. But no trains

A typical busy morning at Lymington Station on the Southern Region. ‘Lymington Town’ sounds busy, even if there only seems to be five ‘customers’ who’d arrived by car when this shot was taken early in 1966. If not ‘a vintage roadscene’ exactly, it is at least a snapshot back in time. A time when it made sense to take the train when fares were reasonable, and it was possible to park your car outside the station, free of charge. And why not? Passengers arriving by car were, after all, spending money on train fares.

Here we have a reminder of those more logical days when, however awful a British Railways sandwich was, you did at least know the train wouldn’t be delayed because of the wrong kind of snow or a sprinkling of leaves on the line. Parked outside the station, we can see a Hillman Minx, a brand new 1964 Ford Cortina ‘1200’ estate (the estate came out in 1963, but the 1500 had awful American-style fake wood side trims), a Triumph Herald estate, a two-tone Sunbeam Rapier and an MG 1100

Here’s a famous ‘road’ brand that, as a result of short-sighted management/changing market conditions/the conservative approach of transport managers (delete to suit your political stance on history), had gone out of business and had to be rescued by another company that was more interested in the factory than the famous ‘waggons’ that were once built there. Yes, it must have been a sad day for Shrewsbury, when the famous Sentinel Waggon Works was taken over by Rolls-Royce.

But then, chances are, Sentinel would have got into trouble sooner rather than later, as the ‘underfloor engine’ format just didn’t work for an artic tractor unit, and the trend in road transport was increasingly towards articulated and away from the traditional ‘wagon and drag’ format. Sadly, the company had somehow er, ‘missed the bus’ with underfloor-engined passenger vehicle orders, even though, arguably, Sentinel had more experience of this layout than most. But diesel shunters for railways? That was something else, surely? Well, actually no, because right up to the 1930s, the Shrewsbury factory was producing specialised steam locomotives and railcars for the world’s railways, mostly for narrow-gauge lines.

The Rolls-Royce ‘Sentinel’ shunter was, we are told, ‘designed for use in steel mills, docks, quarries, etc’… ‘and its clean appearance reflects its simplicity and toughness’, the caption rather clunkily informed us without giving away a single technical fact. What we do discover is that, in 1968, the Sentinel won an Industrial Design Award in the ‘Capital Goods Section’ of the Council of Industrial Design. It looks as though these two locomotives were operated by the Manchester Ship Canal Company where, presumably, running two locomotives on the same track was considered OK!

Here’s a final twist to the ‘road/rail’ story, where these days there’s even a series on TV called Railroad Truckers or something similar but, in truth, we’re back to square one. Road vehicles have been used to shift railway wagons – and even complete engines – way back in steam traction engine days and later, with the arrival of the famous Scammell ‘Hundred Tonner’. Amazingly, while one of the two Hundred Tonner tractors has survived into preservation, the British commercial vehicle industry, once one of this country’s biggest earners of foreign currency, sadly hasn’t.

But we also need to remind ourselves why the Scammell was built in the first place. It was to replace, or at least supplement, the use of steam traction engines to haul brand new ‘out of gauge’ railway locomotives to the docks for export. And, while we might think in terms of ‘steam railway engines’, in truth that included early designs of diesel and diesel-electric locomotives for export to India, Africa, South America, Australia and New Zealand as well

So what’s new? Well, these days, the only thriving part of what was once a UK industry of global reach, seems to be the continually expanding ‘Heritage Railway’ sector, as practically all the new rolling stock for our main lines is made in either Italy, Japan or, if not already then shortly, China, rather than by the staff of the company that’s destined to operate it in Swindon, Derby or Doncaster. And the other change? Oddly, the ‘more efficient’ franchise system has made it more cost-effective to shift rail vehicles by road as, presumably, each little franchise ‘kingdom’ and level of management, wants to make a profit out of all the others, to the point where transporting anything by rail becomes too expensive. So that might help explain why this lovely restored Pullman car ‘Orion’ was being transported by road on a dolly converter hauled by a Volvo F88 6×4 tractor unit. We know the location – Beer in Devon – and we know that the driver must have had his work cut out as the road in this location has a gradient of 1 in 5. What would the Scammell 100 tonner have made of that?

To subscribe to Vintage Roadscene, click here