The Foden two-stroke diesel

Posted by Chris Graham on 27th May 2022

In a different era, the Foden two-stroke diesel could have been a howling success, instead of a crying shame, says Ian Shaw.

The Foden two-stroke diesel was fast in its day, and it still is!

The starter motor barely has time to register before the engine bursts into life immediately confusing one’s aural reference points. Sure the inherent straight-six smoothness is here but it sounds as if it’s running twice as fast as the idle rpm shown on the rev counter. That’s the first clue. There’s a hard-edged bark to the exhaust note, not dissimilar to a Rolls-Royce Eagle, yet the revs rise and fall more suddenly and once out on the road, by the time each 1,700rpm gear-change point arrives, you can forget trucks completely, the exhaust note is pure Austin-Healey 3000! That means it can only be one thing. Possibly the most complex, probably the most charismatic and certainly the most misunderstood lorry engine of its day. The Foden two-stroke.

This great, 12-year restoration easily stands up to harsh-light appraisal.

Foden had its origins in agricultural engineering and Edwin Foden built steam traction engines before embracing new legislation for road transport in 1896 which permitted lorries up to three tons to travel at 12mph without a red flag. Imagine that in London today, being able to attain 12mph!

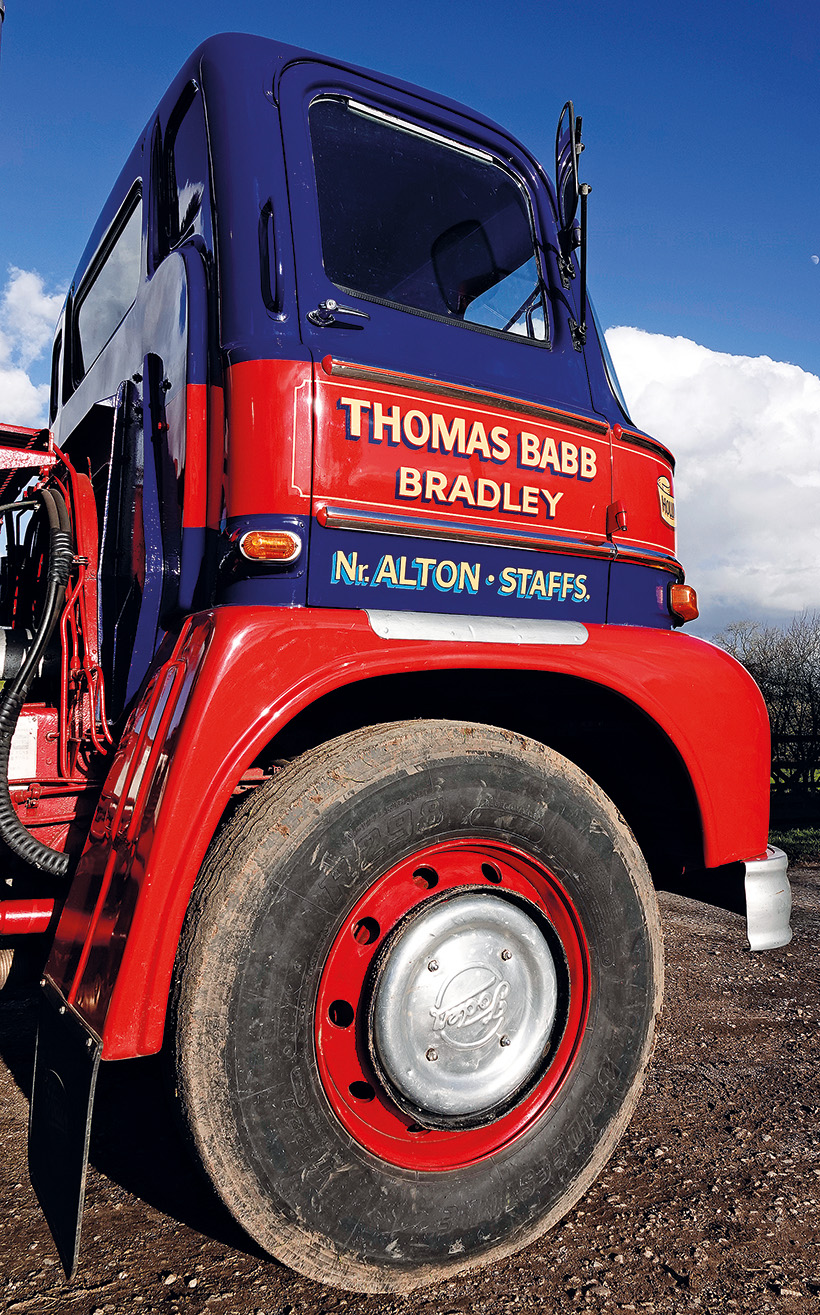

Owner Thomas Babb is a life-long Foden driver and loves the marque.

It would be fair to say that Foden as a marque underwent technical advance in something of a leapfrog manner. Still persevering with steam lorries – albeit developed to a very sophisticated level – when others were turning to diesel, it had to play catch-up, but in what was to become something of a Foden hallmark, it did not do things by halves. Wholeheartedly embracing diesel in 1931, it was widely hailed as the first commercially successful diesel lorry, using as it did the highly-respected Gardner 5L2 engine. Through the 1930s, Foden used the Gardner LW range, in four-, five- and six-cylinder versions and the combination was widely considered to be the best of both worlds – setting Foden as the benchmark for strength and best-engine choice.

Most people’s image of a two-stroke would only have two wheels… not this one.

In the 1930s, the demand for Gardner engines was widespread and Foden found its production of lorries limited not by its own facilities at Sandbach but the ration of Gardner engines. It therefore decided to design and develop its own engine. In that situation it would have been simple – indeed financially logical – to merely build some form of Gardner-copy, but Foden wanted to cut weight, increase payload and leapfrog its competitors again. The decision was made to do this with an engine which promised more power for much less weight and size.

On site; it looks perfectly at home, compact and powerful.

Mention two-stroke engines to most people and they conjure up images of blue-smoking wasp-sounding motor scooters. These petrol two-strokes are the simplest form of the breed. Using ports in the cylinder wall they induct through the lower port which, as the piston descends pushes the fuel/air mix via a bypass up into the combustion chamber, once ignited the descending piston pushes the next induction through the bypass which ejects, the exhaust through the upper port, and the cycle continues. Hence twice as many power strokes for a given crankshaft speed as a four-stroke engine.

Side view of the cab showing nice sign-writing and lining.

So the advantage is more power for less size, weight and complexity, albeit at higher rpm. The downsides are a much less clean combustion – the induction never fully ejects, or scavenges, the exhaust gas – and as the inducted mixture has to transfer through the crankshaft casing to travel up the bypass, then no oil sump can be used. The lubrication, mixed into the petrol, causing the characteristic blue smoke and ensuring the engine type’s gradual demise with tighter emissions regulations. The petrol two-stroke was most successful on two-wheels, with a few notable car applications mainly in Eastern Europe and Saab proving its power-to-weight advantages in rallying. One final characteristic which would be less than welcome in commercial vehicle use, was that since the oil came in with the petrol, on the over-run insufficient lubrication would take place, so a free-wheel had to be used which totally eliminates engine-braking.

From this angle, it even looks like an express train.

Clearly the diesel two-stroke needed to harvest the power-to-weight advantage – the gains here, theoretically being as much as 50 percent – without the many pitfalls. Foden initially utilised a Russell and Newbury reverse scavenging, or loop scavenging, diesel two-stroke, where, like a petrol two-stroke, cylinder-wall ports induct and exhaust as the piston covers and reveals them, but converted it to a uniflow scavenging system. Here the designs of two and four-stroke are mixed in that the induction air is admitted by ports in the lower cylinder wall, but exhausted via traditional poppet valves in the cylinder head.

Close-ratio four-speed main ‘box keeps FD6 on the boil, no pun intended.

To increase charge air density, but also promote better scavenging, the two-stroke diesel utilised one further contemporary technology, the supercharger, usually a crankshaft-driven Roots type. This along with inherently more frequent firing strokes was to give the two-stroke diesel its continual Achilles heel; overheating.

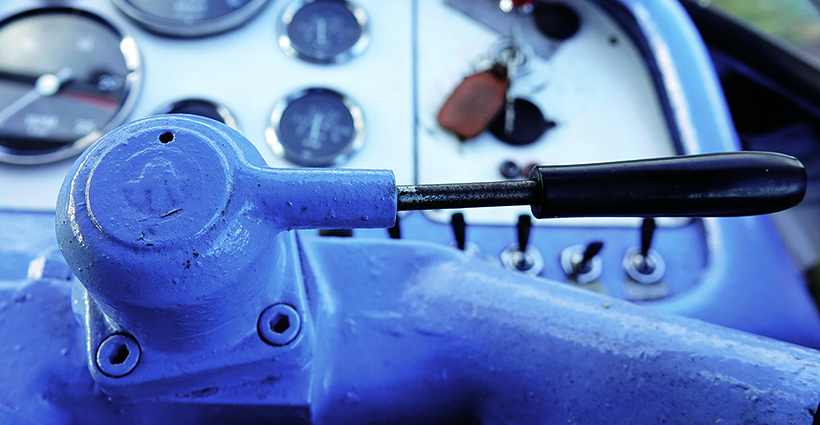

Column lever for air-shifted three-speed epicyclic ranges giving 12 speeds in all.

Foden was aware of all these issues and continual development through the late1940s was to alleviate, if not totally eradicating, most of them. Initial plans were to build the Foden engine as a five-cylinder as it could generate a similar 100bhp to the larger Gardner 6LW, but only three FD5 engines were made. Fuel consumption was better than expected and with news that the Gardner 6LW was to develop more like 115bhp, Foden settled on the six-cylinder, FD6. This 4.8-litre 126bhp unit went into production in 1950 with the 3.2-litre 84bhp four-cylinder FD4 close behind. Success was immediate, with an increase in payload of around 4cwt (200kg) due to the lighter engine, while its lively free-revving nature meant in the hands of enthusiastic drivers hilly routes were dispatched in record time, further increasing productivity. Contemporary reports tell of owner drivers, who were prepared to turn a blind eye to things like speed limits and drivers’ hours such as the ‘Flying Scotsman’ who regularly took his two-stroke eight-wheeler between Glasgow and London overnight in the days of the 20mph limit, no motorways and no tachographs.

Coolant header tank in cab, don’t let the passenger play with the cap!

Drivers were key to the two-stroke’s reputation. Foden’s 12-speed gearbox, itself something of a revelation when introduced in the early 1950s allowed the skilled and enthusiastic driver to make best use of the engine’s characteristics and see favourable fuel usage, while one less attuned to the FD6 could waste gallons making the engine struggle off-song. Of all Foden’s developments to accommodate the characteristics of the two-stroke diesel, this 12-speed transmission was probably the single most significant. Essentially a conventional close-ratio four-speed crash ‘box it drove a secondary three-speed epicyclic gear group. This provided three gear ranges with ratios of a 3.29:1 reduction in low, a 1:1 direct drive in mid and a 0.77:1 overdrive in high. So for instance in fourth gear at 2,000rpm, the lorry would be travelling at roughly three times the road speed in the midrange as it would be in low, yet only on-third faster in high range compared to the midrange. Being epicyclic, only single de-clutching was required to execute the pre-selected change in the same manner as a simple overdrive gear. Foden was to use this 12-speed principle right up to the final models before Paccar took over.

Engine cover dominates cab, blue colour scheme helps calm the cacophony.

Foden’s aim was also to improve low-rpm torque and maximum power through 150bhp to 175bhp across several incarnations of the basic engine design. Gradual improvements to induction and fuel injection saw specific fuel consumption improved by ten percent under test-bench conditions while on the road, tested at a gross weight of 24 tons the improvement was even more impressive.

Rev counter takes prime position, but prominence TEMP gauge is significant.

The increased torque stood comparison with the best four-strokes of the time – the Gardner 6LX – and good fuel consumption could be obtained since the engine was no longer as reliant upon driver skill. The higher power available, coinciding with the opening of the M1 motorway in 1959 which was at that time devoid of speed limits or lane restrictions on heavy goods vehicles, led to a test programme investigating potential earning capacity, fuel consumption and reduced journey times. The test vehicle’s final drive ratio was increased until motorway cruising speeds of more than 80mph were reached. The FD6 Mk6 engine was introduced with a rating of 175bhp at 2,200rpm and when the Gardner 6LXB engine arrived with 180bhp at 1,700rpm, the FD6 was uprated to 180bhp at 2,250rpm and called a Mk6B with peak torque of 424lb.ft at 1,600rpm. As the eight-wheeler gave way to the artic, Foden embraced this too and trials of a FD6 Mk6 in a four wheeled tractor-unit running at 24 tons with a two axle semi-trailer gave a fuel consumption of over 10mpg, favourably comparable with the best four strokes of the time and going someway to counter the FD6’s thirsty reputation.

Nice period details abound on Babb’s S21 mixer.

Further development with the BSA (now owned by CAV) turbocharger produced 225bhp at 2,200 rpm and torque of 600lb.ft at 1,400rpm. A 24 ton eight-wheeler tested by the technical press on the M6 recorded a fuel consumption of 9mpg at an average speed of 57.4mph over a run of 87miles. The engine was smoother than ever and primarily because of the effect of the turbocharger on the Roots blower, both intake and exhaust noise, was reduced. However, cooling problems nagged the FD6 and although some could be put down to poor maintenance, cylinder head cracking problems were now well-documented, something the FD6 never shook off. The marine version fared better and could also use seawater as the cooling medium for the charge-air intercooler, further increasing combustion efficiency, but the road engine program had reached its zenith. A final development, started but never finished, was an FD8. This eight-cylinder inline engine, as a blower scavenged Mk6 version would have given 240bhp and turbocharged Mk7, some 300bhp, with maximum torque in the region 590lb.ft and 800lb.ft respectively. The difficulty in curing the head cracking issues together with trading problems in the late 1970s resulted in a decision to sell the FD engine manufacturing rights and replacement parts business to Rolls-Royce. Sadly, that did not result in further development or manufacture of the FD two-stroke.

A stark warning to Ford Anglia drivers.

The parts resource at Rolls-Royce proved its worth over the years however and Thomas Babb, for one, is grateful it existed. Shown here is his magnificent 1967 Foden S21 FD6 Mk6 180bhp two-stroke. Originally operated by John Doughety in Kent its 6×4 chassis carries a wonderful Winget – then Rochester, Kent-based – chain drive cement mixer. It was acquired in its original green livery by Babb in 2003 where the 12 year-long restoration began. This involved a total strip and rebuild of the chassis itself, replacing cross-members with correct original sections and totally rebuilding the engine. Babb admits initially he thought he was wasting his time, re-lining and rebuilding one cylinder at a time – the FD6 has separate heads per pot – they all seemed in good order. However, the fifth cylinder contained broken piston rings, which obviously would have spelled disaster, proving that you cannot be too careful.

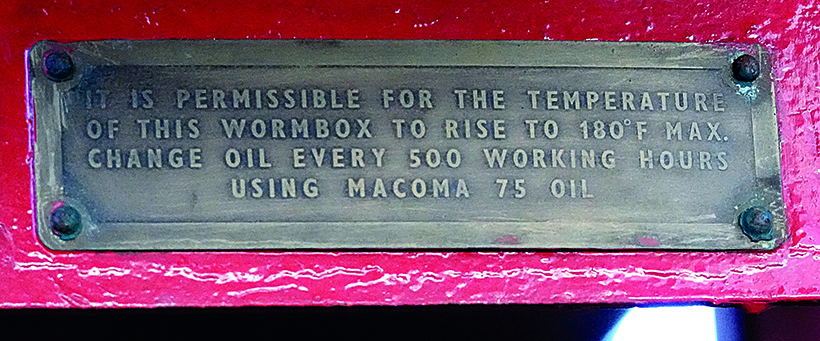

Mixer worm drive service plate could have been lost years ago, wonderfully worn.

Bring the FD6 into the modern era and most of its problems would be eliminated. Certainly the cylinder head and cooling troubles would be no issue. If you can manage to cool a modern Euro-6 diesel, you can cool anything. Modern engine management electronics would allow much finer fuel metering making the issue of total exhaust scavenging a less irksome one, and with (EGR) Exhaust Gas Recirculation part-and-parcel of the modern engine’s emission control, loop scavenging would take on a whole new meaning. The two-stroke’s higher operating rpm and narrow optimum engine speeds would suit the modern automated 16-speed transmissions nicely. If that seems like a lot of complication to embrace an engine which many believe was rightly consigned to history, the two-stroke has one fundamental attribute which does not need to change. Its power-to-weight ratio. We so often chart the rise and fall of British vehicles, manufacturers and developments and lump them under the banner of too-little, too-late. Maybe in the final analysis the Foden two-stroke was just too early for its own good, that’s the real crying shame.

Original Winget mixer drum is driven by a substantial chain.

The author wishes to thank owner Thomas Babb, Stephen Forster, Chris Wallwork and The Foden Society (thefodensociety.org.uk) for access to the chronicle of the FD engine series by Mr RW East BSc. CEng. MIMechE Foden’s Head of Vehicle Development at the time.

Solid build with a sports car soundtrack!

This feature is from the latest issue of Heritage Commercials magazine, and you can get a brilliant, money-saving subscription simply by clicking HERE