Giant steam shovels

Posted by Chris Graham on 23rd January 2021

Keith Haddock begins a series in which he describes the fascinating history and development of the world’s giant steam shovels.

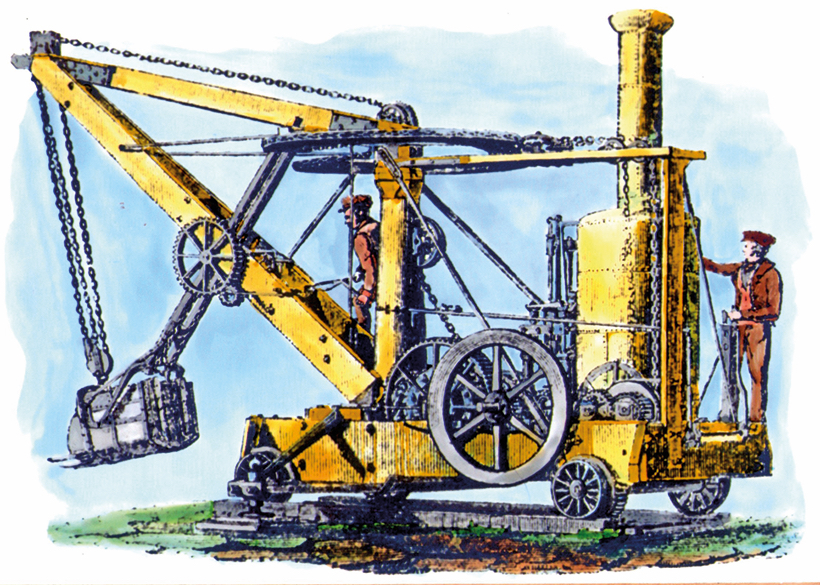

Giant steam shovels: This machine, created by William S Otis, is documented as the first steam shovel ever designed to work on land. It was built in 1835, and patented in 1839.

Steam shovels and often referred to as ‘navvies’ in the UK – a name derived from the pick-and-shovel-wielding labourers who toiled in 19th century railway construction. However, the focus of this article will be the pioneering American and UK manufacturers who built the first giant steam shovels. I’ll be tracing the progress they made up until the point when petrol, diesel and electrically-driven excavators took over the industry.

Steam shovel history

Although development of mechanised earthmoving equipment is largely a 20th century phenomenon, the need to move large quantities of material originated with the Industrial Revolution, and the advent of the steam age in the 18th century. The desire to move people and materials from place to place spawned the earliest forms of mechanised equipment. Because ships were one of the first means of transportation over long distances, it was only natural that the first self-powered excavating machines were floating dredges. These early contrivances helped to excavate harbours, and deepen waterways to make them usable for ever-larger vessels.

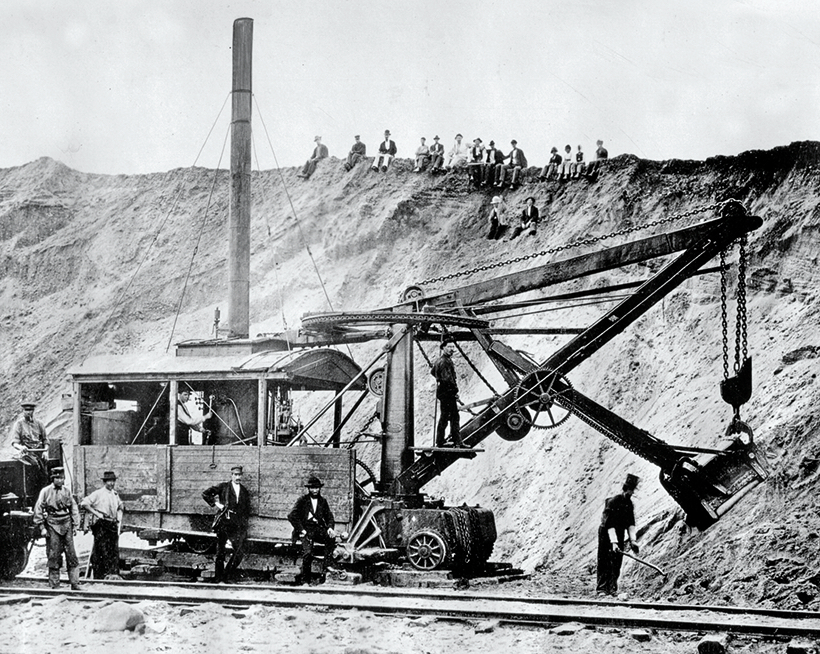

This is probably the very first photograph of a steam shovel. Taken in 1872, it shows an Otis shovel at work on the construction of the Midland Railway near Paterson, in New Jersey.

The birth of the mechanical excavator used on land occurred in America, when thousands of miles of railways across the country were needed. The 1835 steam shovel designed by William S Otis, and patented in 1839, is the earliest known, single-bucket excavator for use on land. Otis was a partner in a firm of contractors which used its own machines for railway construction. When William Otis died of typhoid fever in 1839 at just 26, the shovel patents were strictly held by the family contracting business for over 40 years. But the machines were only built in small numbers.

The idea of mechanised excavation caught on very slowly due to the Otis patents, and the abundance of cheap and plentiful labour. Certainly, this was true in Great Britain, where almost all of the railways up to the early 20th century were built by hand-labour, supplemented with horses and mules.

Patents finally expire

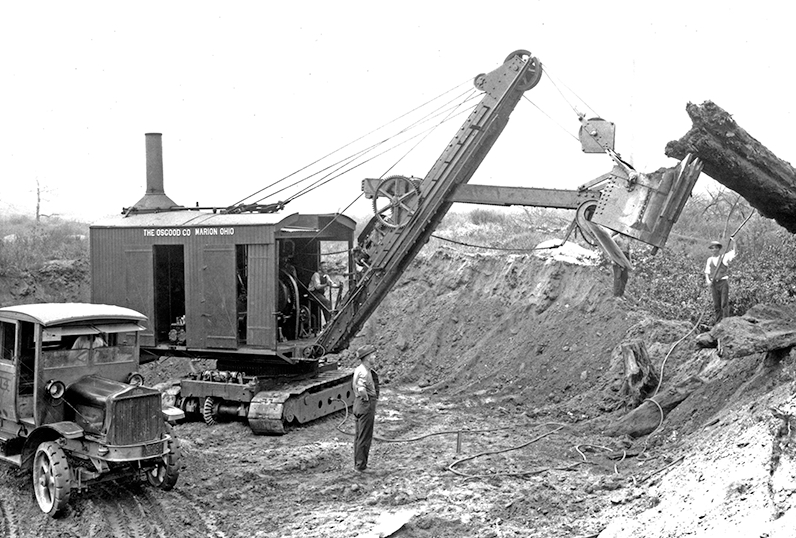

When the Otis patents finally expired in the 1870s, several other companies began building steam shovels in the United States. Most noteworthy were the Osgood Dredge Company of Troy, New York (1875), Bucyrus Foundry & Manufacturing Company, Bucyrus, Ohio (1882), Vulcan Iron Works Company, Toledo, Ohio (1882) and Marion Steam Shovel Company, Marion, Ohio (1884). These companies are the ancestors of an American excavator industry which has advanced up to today’s high-production, electrically-powered machines, which are now the largest and most powerful available in the world.

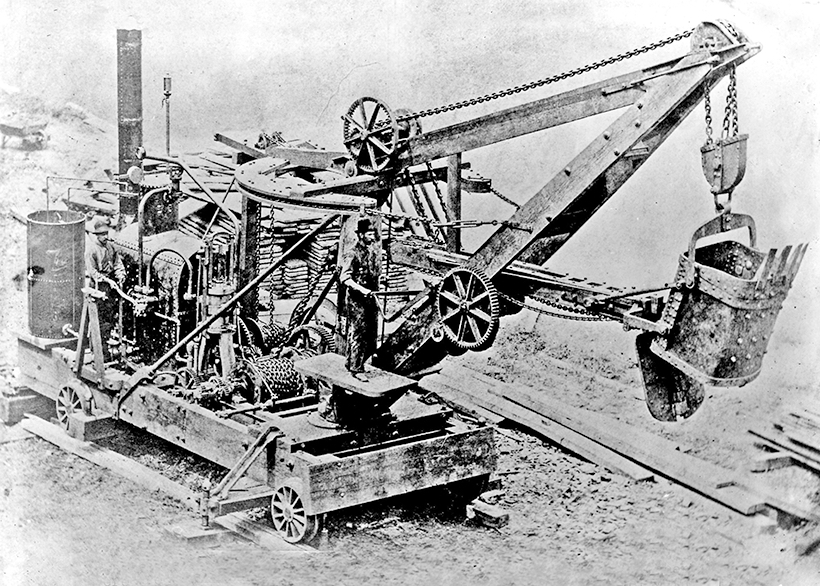

This is an Otis steam shovel with OS Chapman’s improvements, as built by John Souther & Co in the 1860s. It features a horizontal boiler.

Parallel development took place in Europe, when companies such as Ruston Proctor & Company of Lincoln, England (1874), Menck & Hambrock of Germany (1899) and Carlshutte of Germany (1900), entered the steam-shovel industry. Demag took over the excavator line of Carlshutte, in 1925.

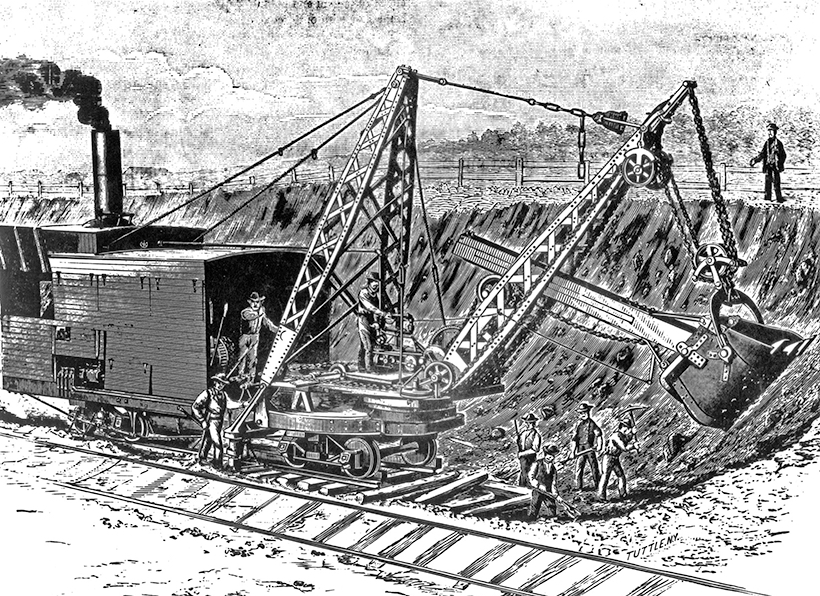

The early steam shovels weren’t fully revolving. Mounted at one end of a standard-gauge railroad car, the boom and shovel assembly revolved about 200 degrees. The steam boiler, main hoisting gear and operator occupied the rest of the car. Because the early machines were rail-mounted, and mostly employed on railroad construction, they became known as ‘railroad shovels’. In later years, even though some were mounted on crawler tracks and found work in quarries, canal excavation and general construction, the part-swing steam shovels were still known as ‘railroad shovels’, no matter what work they were doing.

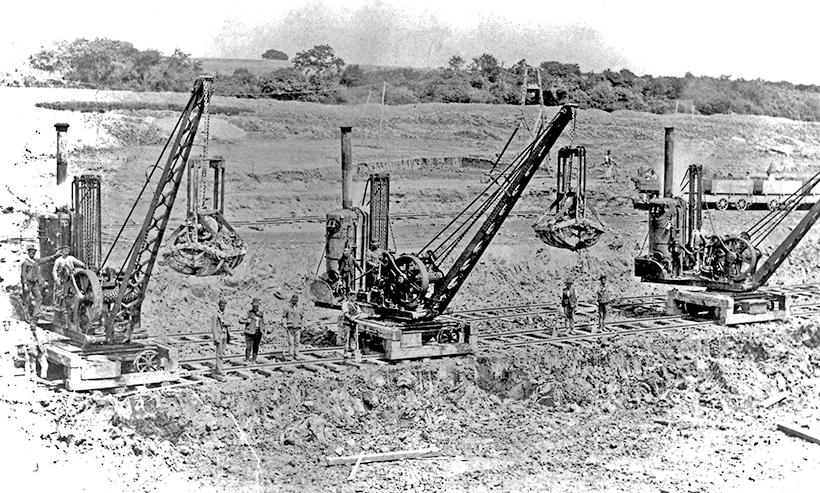

The earliest major mechanised earthmoving project on record was the Manchester Ship Canal in England, starting in 1887. Three of 18 Priestman clamshell excavators helped to move 54 million cubic yards of material.

The earliest major mechanised earthmoving project on record was the Manchester Ship Canal in England, which was started in 1887. Here, 58 Ruston steam shovels, 18 Priestman clamshell excavators and numerous other excavators, worked with 173 steam locomotives and 6,300 rail wagons to move material at rates up to 1.2 million cubic yards per month. In all, 54 million cubic yards were excavated over a six-year period. This project was followed by the much larger Panama Canal, where 77 Bucyrus, a Thew and 24 Marion steam shovels were employed to move 255 million cubic yards between 1904 and 1914.

Revolving in Leeds

The world’s first, fully-revolving shovel was built by Whitaker & Sons of Leeds, England, in 1884. But it wasn’t until well into the 20th century that the revolving shovel became universally popular. The railroad shovel, restricted by its rail mounting and half-swinging boom, was gradually replaced by highly-mobile wheel and crawler outfits, which could swing through a full circle. The last railroad shovel was shipped in 1931, almost 100 years after the advent of the Otis shovel.

This was the first Osgood steam shovel, which appeared 1880. If you examine this illustration carefully, you can trace the two dipper hoisting chains running up each side of the boom and down to the dipper. These chains swung the boom when pulled independently, or hoisted the dipper when pulled together.

A common practice in the early development of excavators, was that the machines were patented by their inventors, who then found a manufacturer willing to build them to their specifications. Examples included the Otis shovel built by John Souther & Co, the Thompson shovel built by Bucyrus, the Dunbar shovel built by Ruston, Proctor & Co, the Barnhart shovel built by Marion and the Osgood shovel built by Starbuck Bros. Iron Works.

The 1920s was a revolutionary decade for the cable excavator, as manufacturers either adapted to diesel- or gasoline-powered machines, or failed completely. Avoiding the steam era, dozens of new excavator manufacturers emerged, especially in America, offering excavators with sophisticated mechanical features and diesel or gasoline power. At the top-end of the scale, machines became much larger and most of them were electrically-powered. A good number of these new companies, however, didn’t survive the Great Depression of the early 1930s, but those that did became the backbone of the excavator industry for the following three decades.

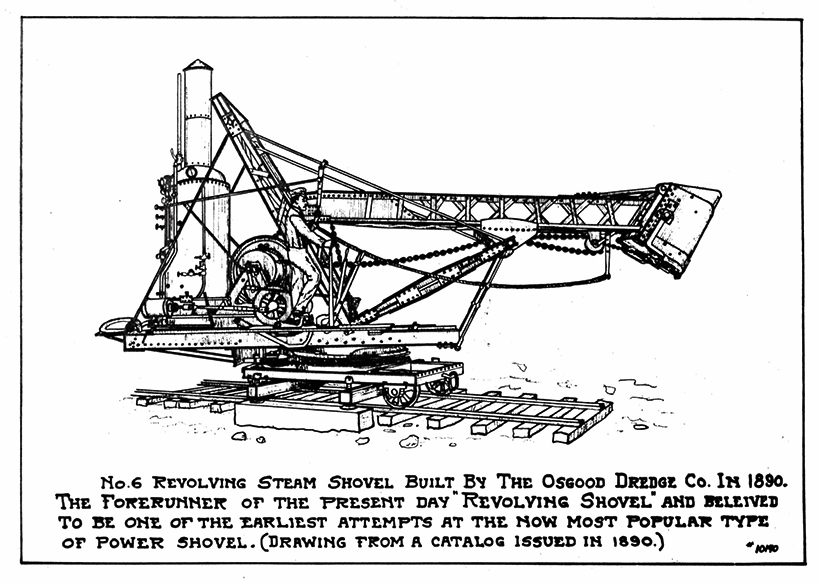

This unusual steam shovel was patented in 1887 by John K Howe, director of the Osgood Dredge Company. Known as the Osgood No.6, it featured a cantilever hoist whereby the hoist rope was fastened to the top end of the dipper arm, instead of directly to the dipper.

This series will feature examples of steam shovels built by companies long ago extinct, but also by companies with familiar names who successfully transitioned from steam to other forms of power. After all, steam was just one form of providing power to an excavator, and many models from the 1920s and early 1930s were offered with a choice of steam, petrol, diesel or electricity for power. In all other respects, the machines were identical.

Otis was the first

As already mentioned, the Otis of 1835 was the first steam shovel and, because of restrictive patents and plentiful labour, it took many years until other types were developed. Although primitive, the early Otis shovel demonstrated the idea of a fixed boom and a crowd mechanism that thrust the bucket into the digging face; the same principle still used on rope shovels today.

A six-cubic-yard Osgood 120 railroad shovel in a western US copper mine.

One of the Otis shovels was reported to be working in England as early as 1843, on the Eastern Counties Railway near Brentwood. As reported at a meeting of the Institution of Civil Engineers in 1845, it appeared to have been successful: ‘The trials of the excavator on the Eastern Counties Railway were made under very disadvantageous circumstances – the workmen were inexperienced; the form of the shovel was not adapted to the nature of the material to be excavated; so few wagons were provided that frequent stoppages occurred due to the inability to carry away the earth as fast as it could be dug. Yet, in spite of these drawbacks, the machine has delivered as much as 100 cubic yards per hour, and the cost of working it, including fuel, wages, wear and tear and interest on capital, did not exceed 50 shillings per day.’

Despite its potential, little progress was reported with steam shovel development until about 1858, when Oliver S Chapman – a close business associate and family friend of William S Otis – improved the design of the Otis shovel. He had married William Otis’ widow, and that allowed him use of the shovel patents. So, an improved Otis shovel was patented in 1867. During the 1870s, several new manufacturers sprung into action to take advantage of the boom in railway construction, especially in America.

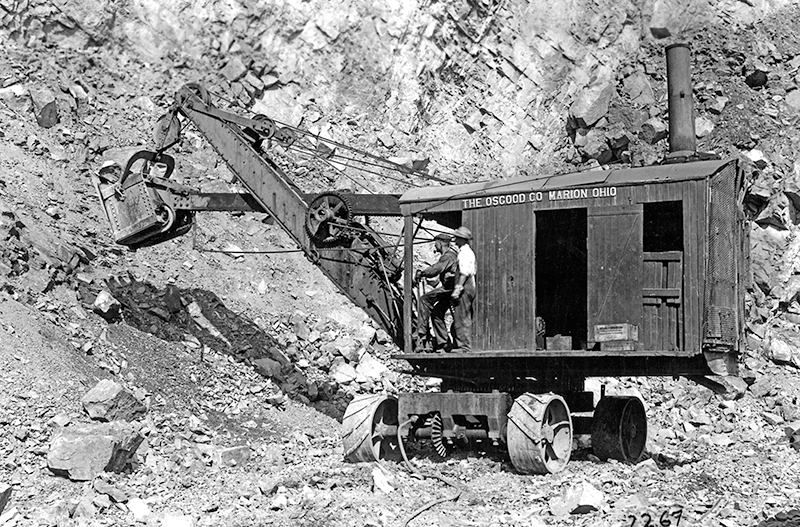

Osgood 73 railroad shovel on traction wheels, photographed in a Kentucky quarry in 1999. This machine is now preserved and operational at the Western Minnesota Steam Threshers Reunion at Rollag, Minnesota.

Otis shovels were initially built by the firm Eastwick & Harrison of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. When Chapmen took over their development, they were built by Globe Iron Works of Boston, Massachusetts. This firm later became John Souther & Company, and records indicate that Otis shovels – with little change in design – continued to be built by Souther up to about 1910.

Osgood’s roots

The Osgood Company roots can be traced back to the very first steam shovel. Jason C Osgood and Daniel Carmichael took out a patent for a dredge in 1846, Carmichael being an uncle of steam-shovel inventor, William S Otis. The dredges were built by Starbuck Brothers Iron Works of Troy, New York.

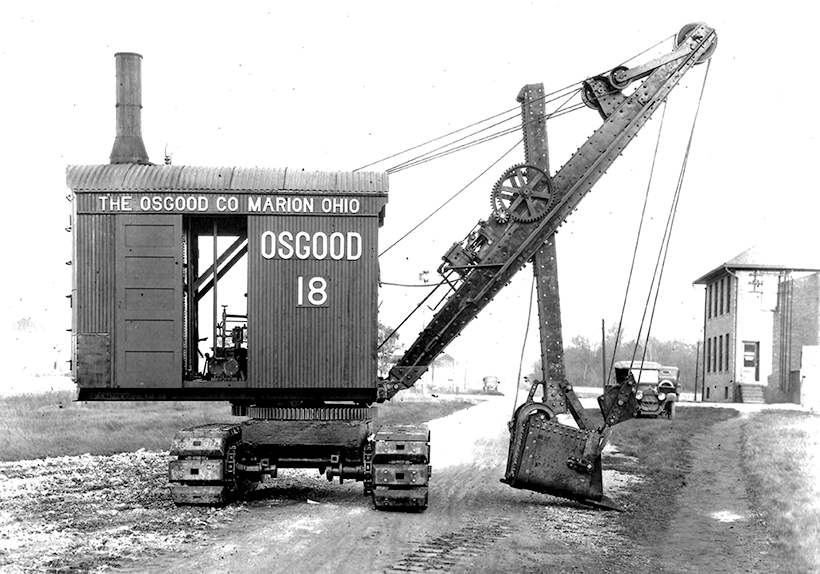

One of the most popular Osgood steam shovels was this ¾-yard model 18, available on crawler tracks or traction wheels.

In 1877, Ralph R Osgood – a nephew of Jason C Osgood – took over the active work of the company and, in 1880, designed and built a new type of steam railroad shovel. This shovel possessed a hoisting feature never used on any shovel before or since. There was no independent swinging (rotating) machinery for the boom and shovel assembly. Instead, swinging was achieved by using two separate hoisting drums and chains; one chain running via the turntable up each side of the boom, over sheaves at the boom point and down to the dipper. Hoisting one chain would swing the boom in one direction, hoisting with the other chain would swing ii on the other, and hoisting the dipper with both chains would prevent swinging. A reversing crowd engine was positioned on the revolving turntable.

This shovel must have been reasonably successful as the first machine – delivered for railway construction in 1880 – was reported by the contractors to have done excellent work. Nine of these shovels, known as ‘Land Excavators’, were supplied in 1882 to the French effort to build the Panama Canal. That same year, in association with James MacNaughton, Ralph R Osgood established the new company name of Osgood & MacNaughton, and production moved from Troy, to Albany, New York. In 1883, the Osgood Dredge Company was founded at Albany.

Another Osgood 18, this one with skimmer attachment.

Unique approach

Another unique steam shovel was patented in 1887 by John K Howe, who was a director of the Osgood Dredge Company. Known as the Osgood No.6, its dipper capacity was ¾ cubic yard, and was one of the world’s first, fully-revolving shovels (Whitaker’s shovel of 1884 was the first). Power from a single steam engine was transmitted through clutches and band brakes to perform digging functions. The No.6’s most unusual feature was that its dipper hoist rope was attached to the top end of the dipper handle, instead of directly to the dipper, which resulted in a cantilever motion.

Osgood Dredge Company prospered and by 1896, apart from a wide range of dredges, offered four sizes of steam railroad shovels ranging from ½ to 2½ cubic yard capacity. It also offered electric power on some machines. An 1890 catalogue shows a dragline that could be mounted on a floating dredge or skids and rollers. But the word ‘dragline’ was not conceived at that time, as the machine was called ‘the No.15 Steam Shovel to Work Backwards!’

An Osgood model 29 one-yard steam shovel on traction wheels.

In 1910, a company known as the Marion Shovel & Dredge Company, was incorporated in Marion, Ohio. It immediately purchased all rights and patents of the Osgood Dredge Company following a fire in 1907 that destroyed that company’s factor in Albany, New York. After the purchase, the Marion Shovel & Dredge Company became the Marion-Osgood Company but, in 1914, changed its name to The Osgood Company to avoid confusion with the Marion Steam Shovel Company of that city.

The Osgood Company moved into full production of steam railroad shovels, followed by a range of modern, revolving steam shovels. In 1924, the range consisted of three sizes of revolving crawler shovels, from ¾ to 1¼ yard capacity, and five sizes of railroad steam shovels from, ranging from 1½ to 5 cubic yard capacities. These could be purchased with rail, traction wheel or crawler mountings.

A 1¼-yard Osgood HDS (Heavy Duty Steam) shovel.

In the 1920s, Osgood’s trade name became ‘Heavy Duty’. Ranging in sizes from ¾ to 2 cubic yards, in quarter-yard increments, the models were identified only by size (cubic yards), prefixed by the letters HDS or HDG to signify ‘Heavy Duty Steam’ or ‘Heavy Duty Gasoline.’ In the 1930s, gasoline, diesel and electric power replaced steam, and Osgood adopted names for its various sizes of excavators such as Invader (½ yard), Commander (1 yard) and Chief (1¾ yard). Osgood remained a moderate force in the crane and excavator business until 1955, when Marion Power Shovel Company acquired all assets and factories of the Osgood Company, including its subsidiaries, the General Excavator Company and the Commercial Steel Casting Company, all of Marion, Ohio.

For a money-saving subscription to Old Glory magazine, simply click here