The car transporter revolution!

Posted by Chris Graham on 30th January 2021

Bob Tuck reveals how the car transporter revolution first arrived to change the new cars sales business in the UK during the 1950s and ‘60s.

Photographs: Ken Glendinning Collection/as stated

The car transporter revolution!: New in 1960, SJR 100 was the first car transporter to be operated by WA Glendinning, of Shotley Bridge. Seen on Front Street in Consett, Ken tells us that this was something of a trial load. The Morris artic had just been painted by Bob Grindle, so it was taken up to JS Robson – the town’s Vauxhall dealer – so that the Burtonwood tail-lift could be tried out. John Thompson was the first regular driver of this outfit.

You could say it was love at first sight. Well, that may be a bit strong but, the first time I saw SJR 100, I was totally smitten. Just like many folk in my home town of Consett, in the north-west of County Durham, the arrival in 1960 of Archie Glendinning’s first new car transporter just blew my mind! I was even more lucky than some as I knew this artic’s regular driver – John Thompson – and, as time passed, John would let me travel with him as and when there was any space in the passenger side of the cab.

In fairness, first dibs on that seat was taken by Archie’s eldest son, Ken, who still vividly recalls the day in 1960 when he went with John – in the family Morris 1000 Traveller – to collect the double-decker at the Rubery Owen plant at Prees, Shropshire, where the Burtonwood tail-lift had been fitted: “The only instruction we got from there was what button did what,” says Ken, recalling how that versatile piece of mechanism worked. “We even encountered our first low bridge,” he added with a laugh as he recounted the trip back to Archie’s yard at Island Garage, Shotley Bridge, where the artic was to be painted by Bob Grindle. “It was a good job John stopped in time to prevent any damage to that tail-lift – we might never have lived that down!”

Ken Glendinning; car transporter authority extraordinaire.

Before new cars started being carried by transporter, the normal method of delivery was for them to be individually driven using trade plates. BJ Henry was one of the first concerns to operate this type of service. And when a big order had to go to the docks – on the south coast of England, for export – the new cars would often travel in a convoy, like this.

Ken has spent his entire working life involved with car carriers and, even now, he’s still asked to attend various customer events. He drove them, operated them, built them – to WA Glendinning’s own requirements – and often repaired or modified them, too. He’s championed them both with his very long involvement with the technical committee of the Road Haulage Association, and then as an ambassador for the manufacturer, Transporter Engineering. And, of course, being a total ‘petrol head’ (just get him talking about his frightening exploits on a go-kart) he’s loved every minute of this continued involvement.

Captain Henry

Ever since the start of motor vehicle production, the delivery of the finished cars from the manufacturing plant to their first owner/supplying dealer, has always been an early requirement. Generally, cars were never registered at this point, so a system of temporary number plates was created to help the motor trade get round the legal need for this first journey on the road. Known as ‘Trade plates,’ they were usually attached to the vehicles by strong, rubber bands (some were even magnetised) and painted red and white – or white and red. Yes, there were two different types, which were called either ‘Limited’ or ‘General’.

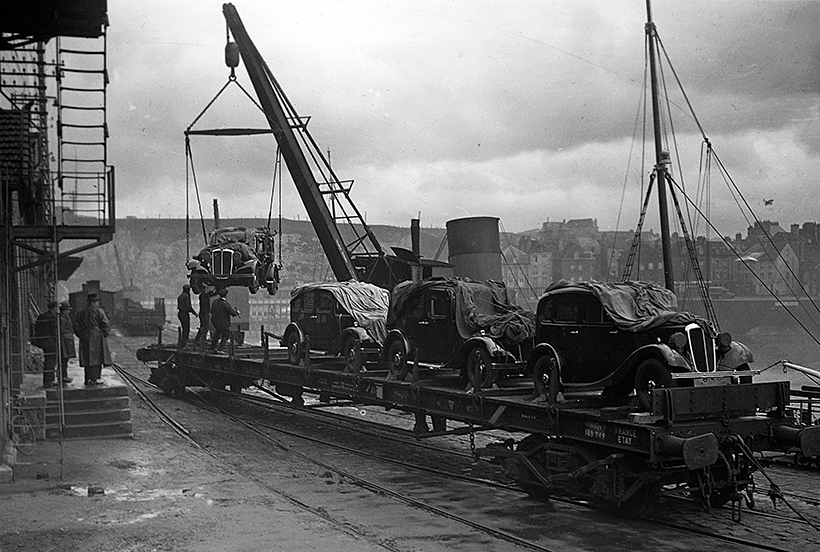

Machinery & Transport Ltd (later known as MAT Transport) was to specialise in the movement of cars by rail, both in the UK and across on the Continent. These Morris-made cars are seen in 1936 being discharged from a ship on to rail at Dieppe harbor, as part of an export movement.

As the names suggest, if you had a ‘General’ one – which cost more to buy – you could do all manner of things, as long as the activity was connected to the motor trade. In those early days, recovery vehicles (wreckers) often used them, and even some early car transporters ran with them on – it was quite a money-saving perk. The far cheaper ‘Limited’ set of plates had tight constraints regarding what they could be used for but, of course, the delivery of new vehicles was permitted.

With the main UK car manufacturers being first located in the West Midlands (Birmingham, Coventry, Oxford) or the South East – Ford at Dagenham – the logistics of getting finished cars around the UK could be quite challenging. At this early time, cars were sold ‘ex-works’, which meant it was the responsibility of the buying dealer to collect the new vehicle from this distant plant. Not too big a problem if you lived in the heart of England but, if the Ford agent in, say, Wick, Northern Scotland, sold a new Ford Anglia, then somebody would have to travel the 660 miles or so to Dagenham, to collect it, then the 660 miles to get it back to base. That was quite a time-consuming trip, especially given that the brand new vehicle had to be driven at a ‘running-in’ speed.

Operated by Commercial Carriers of Detroit, this is an example of how car transportation was done in the USA. Such visions were to prompt the building of car carriers in the UK.

Gap in the market

One man who spotted a gap in the market with regard to new car delivery was Captain BJ Henry. During the First World War, he’d struck-up a friendship with William Morris (of Morris car fame) and, in 1919 and with Morris’ encouragement, he began offering a delivery service from the Morris factory at Cowley, near Oxford. Of course, anyone (with a suitable driving licence) could be a ‘plater driver’, and that included me on a memorable run to Coventry to collect a Hillman Super Minx in 1964. But where the Henry service was to lift itself above the also-rans, was in the sheer professionalism of his operation.

Henry felt that delivering a new car by road required an entirely different driving technique, with car appreciation and sympathy being of paramount importance. Yes, while some other trade-plate concerns would just use anyone who could drive – as and when demand came up – Henry’s even road-tested prospective applicants before offering them a job. And, with days when perhaps more than 50 brand new cars were heading to the docks at London or Southampton for export, then BJ Henry would utilise motor cycle outriders to ensure there was no problem with these convoys.

The first four transporters operated by BJ Henry were built by Brockhouse. Having two fixed decks, the tractor unit and semi-trailer had to be uncoupled, so that the top deck could be loaded using a system of ramps. The lower deck was loaded once the outfit had been coupled together again.

With huge movements of vehicles like this, it’s not surprising that railway operators began to show an interest. And, in 1926, A Kunzler and AH Moser got together to form Machinery & Technical Transport (later to become MAT), and this company was to pioneer the export of cars to all parts of Europe, by rail. It also identified that shipping them long-distance by rail around the UK could be a money-earner. Although double-handling (putting them on and taking them off the railways), plus the aggravating prospect of damage from stone-throwing vandals from overhead bridges, meant the railway movements could have their problems.

However, by the late 1940s, the arrival of another idea – from the USA – was to sow the seed for all manner of change in the car-moving world.

Rover was also an early operator of the Brockhouse transporter, although a second axle was required in the semi-trailer build to take the extra weight of four Land Rovers. (Pic: Commercial Motor)

Four at once!

I often think of the story John Thompson told me of the day he was sent with SJR 100 to the Rolls-Royce factory, to collect a brand new Roller for a customer in the North East. The collection had been arranged, but John was to meet a solid barrier when he tried to take it out of the factory: “It’s not going on that thing,” the incensed RR man apparently said. His argument – which was put across quite forcibly – was that the car had a wheel on each corner and a lot of pride had gone into its build so that it could be driven on the road, not carried by transporter!

John left the factory without that car (which was later delivered under its own power), but it wasn’t long before manufacturers – like Rolls-Royce – dealers and even their customers, were clamouring for vehicles to be delivered on a carrier. However, Ken reckons the industry’s sales pitch of ‘Nothing on the clock’ was one that road hauliers actually championed, so that they had the impetus to enlarge their road-going fleets.

Leonard Lord – the head of the Austin Motor Company – was to have similar transporters in service during the late 1940s, although this outfit actually dates from 1956.

The first, specially-built UK car transporters arrived on our roads during 1948/49. No surprise that BJ Henry put four artics into service and, with them mainly running from Cowley to the docks, these outfits were bannered as carrying ‘Nuffield Exports to the World.’ Also, it was no surprise that Leonard Lord – then heading the Austin Motor Company – had some similar transporters built to carry newly-built cars, after seeing the concept at work in the USA. Although the Nuffield Group (Morris and others) would join up with Austin in 1952, to form the British Motor Corporation, there was a lot of long-standing rivalry between these two manufacturers, as to who was the best.

The best UK transporter builder of the time was to be Brockhouse. But, while its first carriers had a lot of innovative thinking to them, they still required the tractor unit and semi-trailer to be unhitched so the trailer could be wound down (by hand), to as low a loading height as possible. Yes, with two fixed decks, getting a total of four vehicles on board required a lot of muscle power to then raise that partially-loaded trailer to enable the tractor unit to be hitched on again. Unloading was, of course, the reverse of the loading procedure, but eventually Brockhouse was to incorporate hydraulic rams – built by Bromilow and Edwards (later known as Edbro) – to move that upper deck.

By 1956, Brockhouse was incorporating hydraulic tipper-style rams to raise and lower the upper deck. It developed this design to also utilise a set of roller guides to hold the moving deck in position. Seen running on ‘General’ trade plates, the load on this Silcock Ford Thames is a mix of two-door Ford Anglias and four-door Ford Prefects.

Carrying more

Like other specialised operators, the car-transporter business generates revenue depending on the number of vehicles being delivered. True, the rate will vary with the transport distance but, being able to carry as many vehicles as possible has always been the Holy Grail of moving the metal. In these early days, when vehicles weren’t too heavy, a fully-loaded artic transporter with four cars on board, might only weigh 10 or perhaps 12 tons, gross. So, while it was only half the weight of, say, a maximum weight 22/24 tons gross general haulage eight-wheeler (or four axle artic), it was almost physically impossible to safely get any more fee-earning vehicles on board – or was it?

Well, we’ll address the juicy prospect of using rather cumbersome rigid vehicles towing drawbar trailers (and carrying eight vehicles) in the next part of this story. But, one man who quickly identified how to add 25% to the normal, four-car load of a Brockhouse semi-trailer, was William E Herbert, chief designer at Carrimore Six-Wheelers Ltd. Then based in Finchley, North London, Herbert was assisted by chief draughtsman AE Liner, plus draughtsman Alan Cooper and, between them, they devised a fascinating concept which gave their company a huge impetus in this specialised field.

By 1955, Carrimore Six-Wheelers were coming into contention. The early offerings could carry a similar, four-vehicle load to the Brockhouse. Note on this MVC outfit, how the length of the top deck is virtually the same as that of the bottom.

Although Brockhouse was offering a top deck that could be lowered, this only hinged from a point close to the front and, while it was a steep climb up the loading ramps, that wasn’t a problem. Carrimore’s revolutionary idea was the swinging link, which allowed the entire top deck (when lowered), to first swing backwards, then come down to a far lower height. And as the idea was developed (into the Mark II version) the top deck was extended right out over the tractor unit’s cab. The result was the extra space needed to carry a third car on the top deck – making five in total. It was no wonder that operators began clamouring for this new carrier.

Shotley’s finest

In 1960, the tight constraints of vehicle licensing meant that Archie had to take Consett’s respective Vauxhall and Ford dealers – Jakey Robson and Tom Gordon – to the licensing court, and thus prove the need for a new ‘B’ licence for what would be Glendinning’s first artic. In truth, many car dealerships across the length and breadth of the country, never really knew when their newly-built cars would be delivered from the factory by their agent. So, the opportunity to have a haulier right on the doorstep, that could collect five new cars on a two-day round trip to the factory, was something they’d certainly support.

By 1959, the length of the Carrimore top deck had been extended to ensure three vehicles could be carried up top, adding an extra 25% of revenue-earning cargo to the transporter’s load.

With a suitable ‘B’ licence issued, the next problem for Archie to address was what outfit to buy? The Glendinning, all-rigid (mainly tipper) fleet then was generally a mix of multi-wheel, heavy-duty Leylands and Morris lighter-weight four-wheelers. He soon identified the Carrimore Mark II was the trailer to have, but this had a long lead time for delivery: “I’m sure it was Dougy Robson, from Hexham, who suggested we should buy a Taskers,” says Ken, “as I think they had one in service just before us.”

With two straight decks, the Taskers was fitted with a rear-mounted Burtonwood tail-lift, so each car was lifted/lowered to the relevant deck height, so it could be driven on to the semi-trailer. Controls for the lift were fitted at the rear, nearside at ground level, and also to the lift itself, so it was easy enough for the car driver to lean out and press the relevant button. But operators had to be careful – very careful – not to press the wrong button, and tip the car off backwards. I’m sure that it was done!

Known as the sloper – for obvious reasons – this style of transporter could only carry three vehicles. Of course, high-top Land Rovers like these weren’t really suited to being carried on the lower deck of conventional transporters. Built by Abelson’s of Sheldon, other important advantages of this vehicle included its cheapness and the speed with which it could be loaded/unloaded.

Ken recalls the tractor unit for this new semi was a 12-ton gross Morris urban. It was fitted with a Taskers automatic coupling and, as Scammell devotees will tell you, it was a very good copy of what they had been using for lighter-weight operation. When the Scammell patent ran out in 1954, all manner of folk used the idea, but the Tasker one was said to be the best.

This tractor unit was extremely light, tipping the scales at just less than two tons 10cwt. A quirk of the law then in force, meant that anyone aged over 17 and with a driving licence, could drive such a vehicle; in those pre-HGV licence days, you normally had to be over 21 to drive anything more than three tons, unladen. So, it was no wonder that, once Ken got to such an age, he took the vehicle down the road for as much time away from his apprenticeship as the Consett Iron Company would allow.

The Cooper Car Company was to work miracles on the standard Mini; its Mini Cooper S even became a Monte Carlo Rally winner. Its products were also raced all over Europe, and the company utilised this specially-made transporter (with space to carry all manner of spares, too).

For a money-saving subscription to Heritage Commercials magazine, simply click here

When loading the Carrimore, a driver often reversed the first vehicle on so that the long, rear overhang could project in front. Here, the Furness & Parker driver seems to be in the process of raising the upper deck, and is watching to ensure the back of the Triumph Herald doesn’t strike the back of the Leyland Comet’s cab.

With excess rear overhang – like the one on this Bedford CA scuttle and chassis, the driver of this Dealers Deliveries TK Carrimore has jack-knifed his outfit to allow the open chassis to be reversed to the extreme end of the top deck. He’d also need to adopt a similar jack-knife position when unloading.

With three Bedford CA vans on top, this load makes me feel twitchy, especially about the prospect of encountering a side wind. Mamma Mia!