The fascinating history of Tarmac Ltd

Posted by Chris Graham on 4th March 2022

Peter Morrey looks back at the fascinating history and development of UK civil engineering giant, Tarmac Ltd.

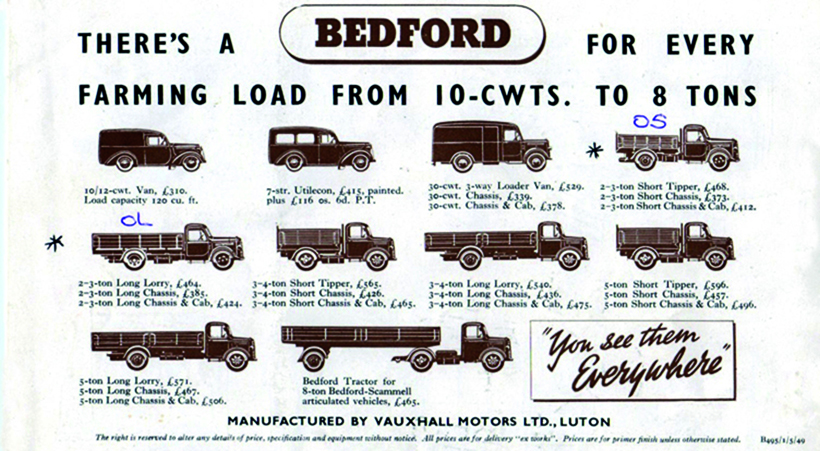

A 1947 Bedford short chassis two-to-three-ton tipper that father’s firm had, seen at a building site in 1952. In 1949, they had purchased an extra Bedford long chassis two-to-three-ton flat-bed lorry for fetching the roof timbers etc.

My early days were spent in and around the sites for building homes, with my father Eric and his brother Bob, who were small house-building contractors. An old pal of father’s was ‘Bunny’ Barlow; a nickname given to him when he was a Spitfire pilot in the Second World War. He got shot down in flames over the English Channel. In 1946, he returned to his position quite high up in the management of Tarmac Ltd, he suggested to father that I should apply to Tarmac Construction to be a trainee civil engineer, which I did in 1956.

I started working for Tarmac Ltd in the Civil Engineering department in 1956, as a junior in the drawing office. I had to go quite regularly to a large drawing office for the Roadstone department, to get prints of drawings by senior engineers from the construction department. There were five men in that drawing office, among them was my uncle, Ken Jackson. He had worked for the company since pre-Second World War until his retirement, in 1970. By the time he retired, he was the Health & Safety Officer for the group.

The two lorries Morrey Bros had indicated on this Bedford advertising brochure issued in 1949, the two to three-ton short chassis tipper and the two to three-ton long chassis flat-bed lorry.

Immediately to the rear of the drawing office in 1956, ran a railway track half a mile away from Stewart & Lloyds Blast Furnaces to Tarmac Roadstone mixing plant. These were carried by a diesel/electric shunting engine with a train of ladles into the tipping point, while the slag was still white hot. The slag heaps would take a day-and-a-half to cool, leaving a hard crust with the inside still warm and semi-liquid. It would then be broken up after cooling by two Ruston-Bucyrus 22 RB tracked cranes, which had a wrecking ball weighing a quarter of a ton. The residue would be put through a rock crusher, and then mixed with the heated tar in a revolving Tarmac making machine.

I recall my friend, Roger Davis – a few years older than me – who worked at Stewart & Lloyd Ltd (British Steel Ltd from 1959) in a team of metallurgists. Roger told me something of the conditions within the works. For 24 hours a day, they manufactured iron in two enormous blast furnaces, using iron-ore, creating steel with slag as a by-product. The furnace crew worked in a tremendous amount of heat, so much so, that the management had to provide two pints of mild ale beer per man, per day, from the Forge Hammer public house in Manor Spring Road, to ward off dehydration.

One of the two Bessemer Blast Furnaces at the Hickman Iron & Steel Works, which became Stewarts and Lloyds Ltd/British Steel Ltd in the Ettingshall/Bilston works from which slag was poured for Tarmac’s mixing plant.

Tarmac started in 1902, when Mr E Purnell Hooley, the Nottingham County Surveyor who, quite by chance, saw a barrel of tar which had dropped off a passing horse pulling a dray wagon. The barrel burst on contact with the ground, and poured on to the laid stone of the road. To clear up the mess they spread a quantity of slag dust from a local iron works over the sticky spillage and, after a while, it mixed together into a tarred macadam. This then produced virtually no dust due to dray wheels, and wasn’t rutted by the wheels of passing traffic.

Mr Hooley obtained a British patent for mixing waste blast furnace slag with tar for road surfacing. 1903, saw the main works at Denby where the business was brisk for road surfacing, Hooley formed the Tar Macadam (Purnell Hooley’s Patent) Syndicate Limited. By 1904, Hooley had taken out a US Patent, and was looking out for American opportunities.

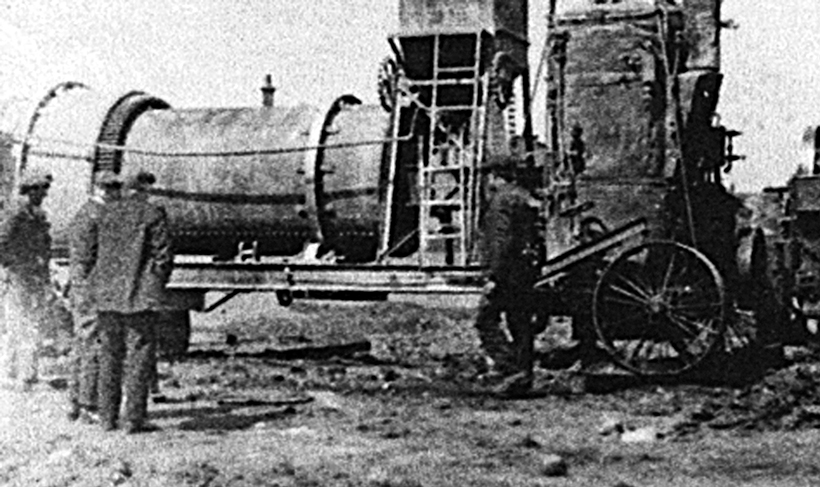

Tarmac’s mixing plant in the 1920s.

In 1905, certain financial difficulties were evident with Hooley’s project but for the intervention of Sir Alfred Hickman, MP for Wolverhampton. Sir Alfred took over the Tarred Macadam business, he had a thriving business as iron master with a large iron and steel works at Ettingshall/Lanesfield, where there was plenty of waste furnace slag derived from the iron-making process. He became the chairman of Tarmac Ltd, and it became a public company after Sir Alfred died in 1910, with orders flooding in for Tarmac’s Roadstone.

Sir Alfred’s son, Edward, was his successor and set aside approximately six acres of land to mix the crushed slag with heated tar to produce Tarmac, from adjacent iron works at Ettingshall. The white-hot slag was extracted from one of the Bessemer-style Blast furnaces, 24 hours a day and sent, via a shunter steam rail train, and later a diesel engine/electric shunter with ladles in tow along a private track, with white hot slag to the tipping point, the track was two metres in height from the ground. When the slag was cool, a gang of workmen with sledge hammers would break up the slag to small size, then it was taken by cart to the Roadstone mixing plant.

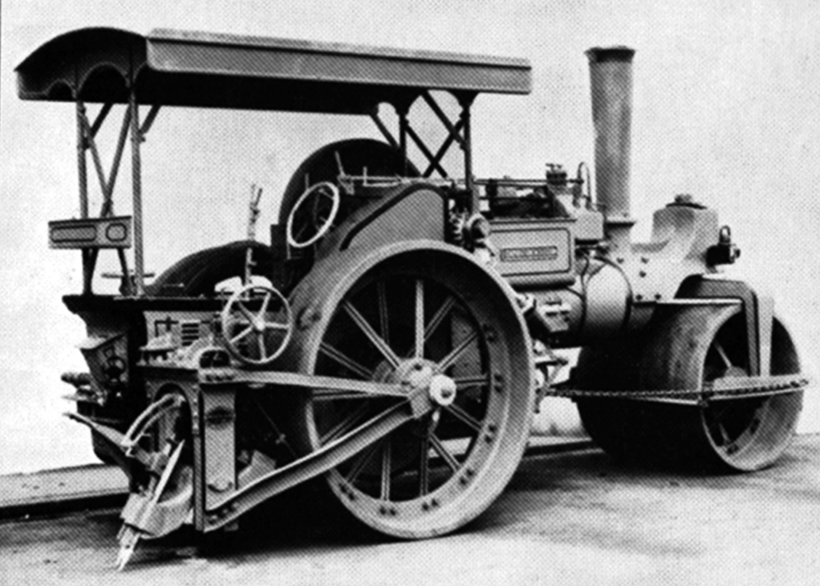

One of Tarmac’s steam-powered road rollers; many machines of this type were used on crushed limestone roads.

Tarmac’s plans were spoilt by the First World War. The company secretary, Mr Comyn, had a good relationship with Sir Henry Maybury of the government’s Road Board which, in 1914, led to large quantities of Tarmac being supplied via its Middlesbrough works to France, to build the much-needed roads to carry our equipment for the armed forces ordered by the War Office, which were dispatched for military use. In 1916, the Road Board approached Tarmac to ask if crushed slag could be supplied to urgently improve roads through French battlefields; the slag was crushed at the works of Ettingshall, Derby and Middlesbrough, and was shipped to France through until 1918.

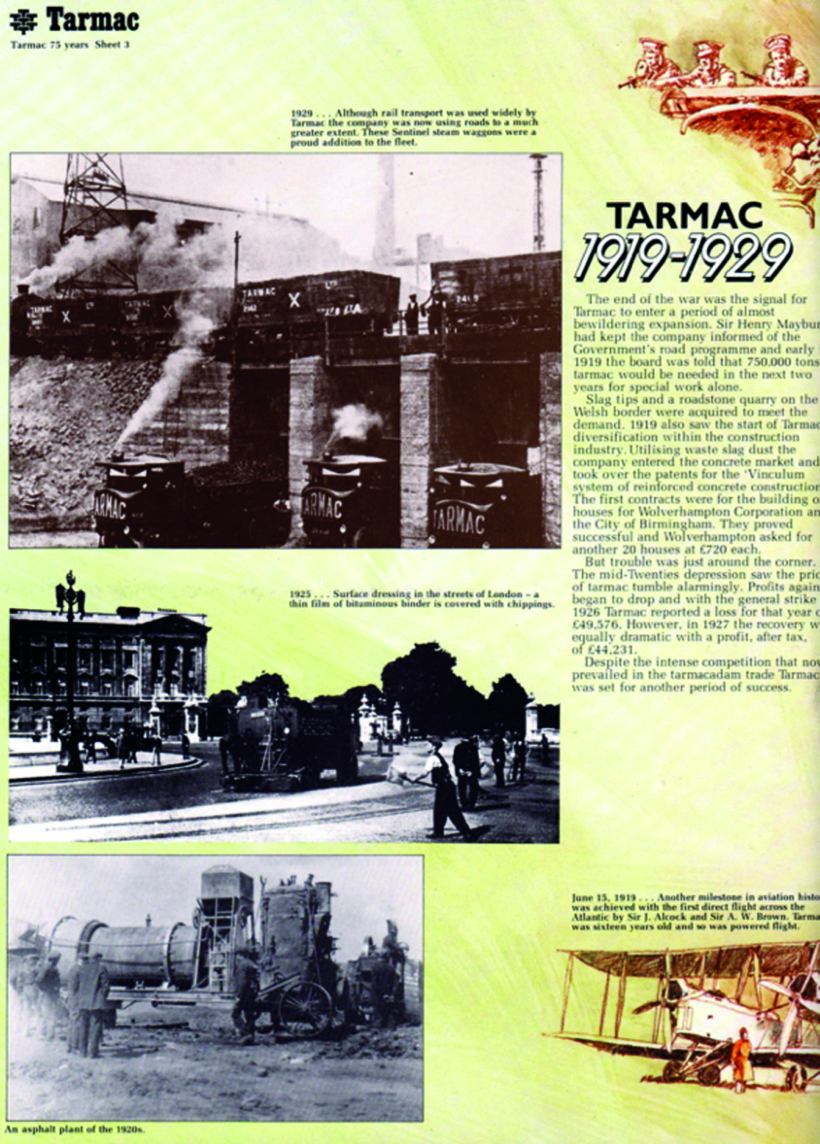

Tarmac entered a period of almost bewildering expansion, realising the amount of fine dust that was created when the men breaking up the slag with sledge hammers, it was considered that the slag should be added to materials for the production of concrete. This was a success. The company acquired the patent for Vinculum Concrete by 1919, and began transporting slag dust to the concrete mix production. Slag tips and Roadstone quarries on the Welsh border were acquired to help towards the 750,000 tons of crushed slag for the UK government.

Tarmac’s Vinculum works where products such as hard-pressed slabs, kerb stones and lintels for the construction business were delivered by lorries.

It was for that reason that they started to use many Sentinel steam wagons, paid for by the sale of a great number of Tarmac-liveried railway wagons. The method of transportation of crushed Roadstone, TarmacTM, Settite (warm bitumen macadam) was introduced in 1932, by 1938, Asphaltic Grittite or cold asphalt was introduced and by then Tarmac Vinculum were busy supplying a host of kerb stones, lintels and blocks for the construction industry.

1919 also saw the start of Tarmac’s diversification within the construction industry. Utilising the enormous quantity of waist slag dust made the company enter the concrete market, it took over the patents for the Vinculum system of reinforced concrete construction.

Sentinel six-wheeler steam wagon. At the time owned by Peter Walker and Diane Carney of Glasgow. (Photographed in 2004, by Paul Bishop)

With the steady rise in demand for road making and construction equipment during the 1920s to 1930s, Tarmac delivery changed from railways to roads. In 1935, the company switched from the use of cumbersome Sentinel steam wagons, to petrol-driven wagons. There were a number of Sentinel steam wagons left which Tarmac put into the task of hauling from the local slag tip which was leased from Lord Dudley, hauled into the road-making material in Ettingshall.

One of the many ‘Super-Sentinel’ wagons has the registration number UX 4138, works number 7757, with chain-driven double drive, and it was sent out from the Sentinel works in Shrewsbury in 1929.

The illustration above shows the rail bridge within the Ettingshall works loading Sentinel steam wagons in 1929.

The ‘Super Sentinel’, chain-drive, six-wheeled waggons of 1929 were a very proud addition to the Tarmac fleet. One of the many later Sentinels, a 1933 S6T with the wagon number 8821, was owned by Peter Walker and Diane Carney in 2004, and is shown here looking most elegant in its Tarmac livery. It was originally one of a batch of six prototype, shaft-drive wagons, the ‘S’ standing for ‘shaft-drive’, the ‘6’ for ‘six wheels’, and the ‘T’ for ‘tipper’. It has some features of the earlier ‘double-geared’ tipper, which was an improvement on the ‘Super Sentinel’. The engine is fundamentally different from the preceding wagons in that it has a four-cylinder, single-acting steam engine, as opposed to the two-cylinder, conventional, double-acting steam engines of the earlier ones.

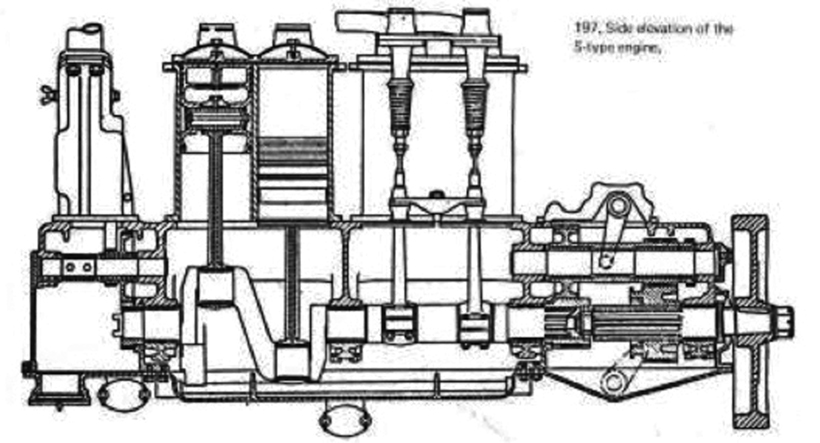

A cross-section of the four-cylinder Sentinel S-type steam engine.

Later in 1933, the Sentinel ‘S’ (shaft-drive) model came on to the market. It was made in three different forms; the S4, four-wheeler, the S6, six-wheel rigid and the S8 eight-wheel rigid. The S6T DA six-wheel tipper was designed to take a payload of 10 tons 14 cwt max. The newly-designed engine was a four-cylinder, single-acting, trunk piston unit, horizontally mounted beneath the framing, and made in unit with a two-speed gearbox. The cylinders had a bore of 5.5in and a stroke of 6in, and the engine developed 124hp at 800rpm, at 50% cut off. The valve gear was of the cam and poppet-valve type, and the reversing lever gave four positions of control – 40, 50 and 90% in forward gear, and reverse speed.

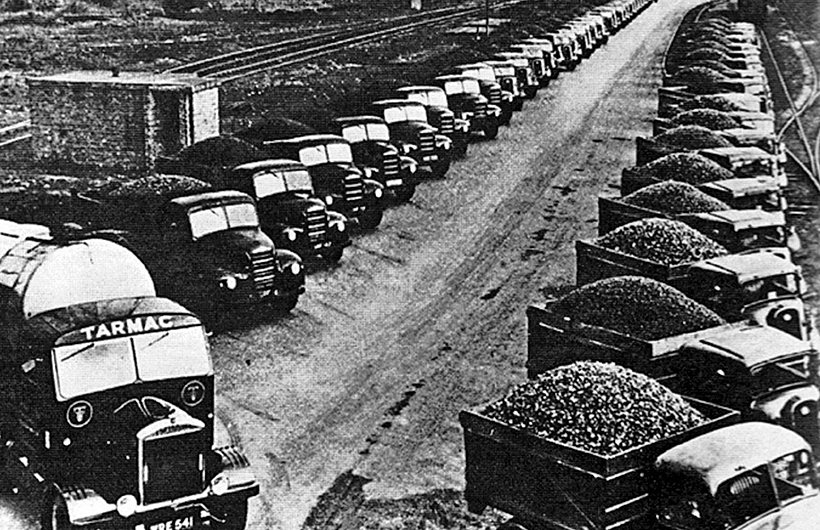

An articulated Tarmac tar tanker and approximately 40 Ford V8 and more modern short wheelbase tippers in the 1950s.

The 1937 Super-Sentinel S-Model, shaft driven was brought on to the market in three different forms; the S4 four-wheeler with a payload of six to seven tons, the S6 six-wheeler with a payload of 12 to 13 tons and the S8 eight-wheeler with a payload of 12 to 13 tons. The S-Model had all the expected refinements found in a petrol-powered commercial vehicle – a roomy, enclosed cab, more modern chassis design, mechanical stoking and automatic water-feed, a well-known Sentinel cross water tube-type, boiler working at a pressure of 250psi, with quick acceleration and economical in operation.

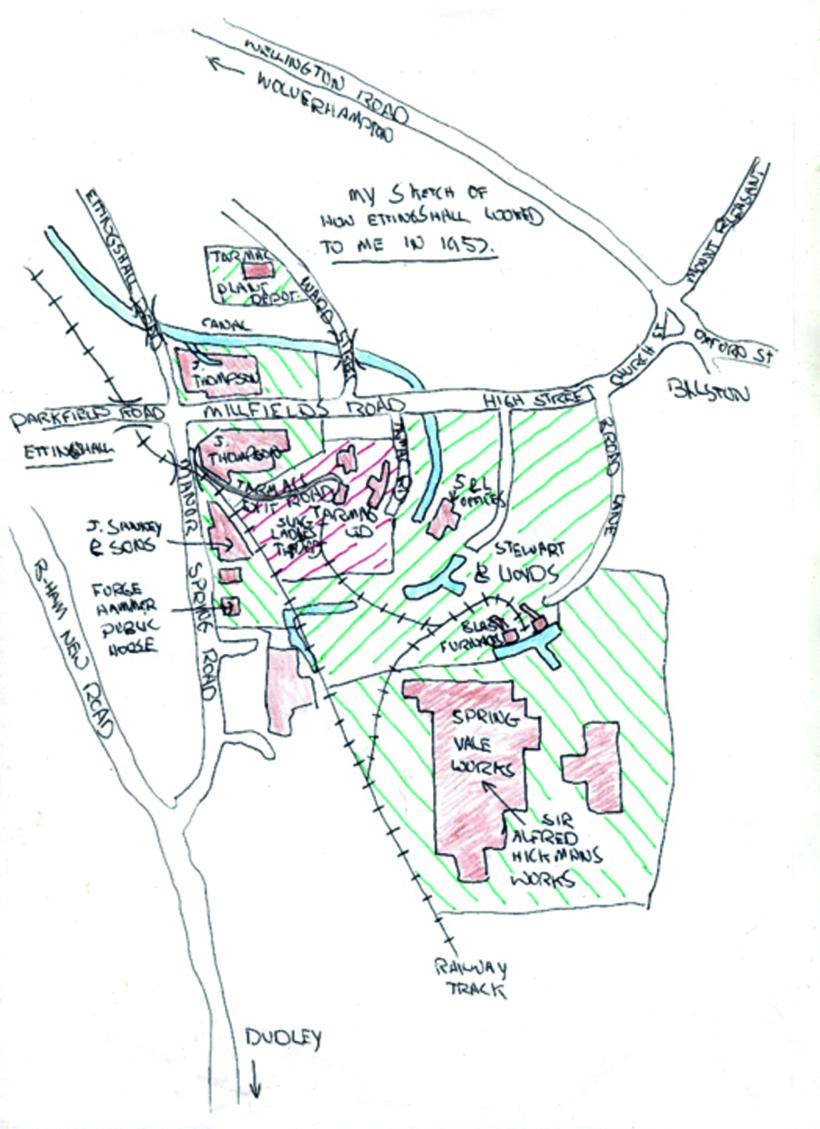

Peter Morrey’s impression of Tarmac’s yard in 1957.

Tarmac Roadstone had its mixing plants for ‘tarred macadam’ road-surfacing materials at Ettingshall, Middlesbrough, Skinningrove, Scunthorpe, Corby, Cardiff, Irlam, Crown Wharf (Deptford) and Shoreham. Tarmac Vinculum was busy providing a host of concrete products for the construction industry, the area of the yard covered about six or seven acres.

Tarmac was bordered on the Bilston side by the iron smelting works of Stewart’s and Lloyds, which became British Steelworks company. On the south-east side, or toward Spring Vale, was the remains of the old established Staffordshire Steel & Iron Ingot Company.

The steelwork’s Bilston locomotive ‘Philip’ pulling the slag ladles back to the blast furnaces from Tarmac’s slag tipping point, by courtesy of Stewart’s and Lloyd’s/British Steel Ltd. They kept another three engines in the loco maintenance shed. (Photo taken after 1963).

I was elevated to the site offices as a junior engineer in 1957, on the contract for building the office block called ‘Head Office Extension 2’ for Tarmac Ltd, next door to the original head office at Ettingshall. The senior civil engineer was Frank Burdon and, under him were the engineers John Mottram, John Thomson and me. The wooden office was next to the restaurant catering for about 100 Tarmac people, opposite the building site on Tarmac Road. Everyone on the site got used to the noise, tar smell, burnt slag and the noise of wagons carrying Tarmac Roadstone every five minutes to all parts of the midlands.

I eventually started my own small company hiring out hydraulic excavators and tipper trucks in 1961, after I had spent an amount of my spare time at Tarmac’s Plant Depot in Ward Street, Ettingshall, in 1957. They had a number of the early types of JCB and Whitlock-Dinkum hydraulic excavators, which particularly interested me.

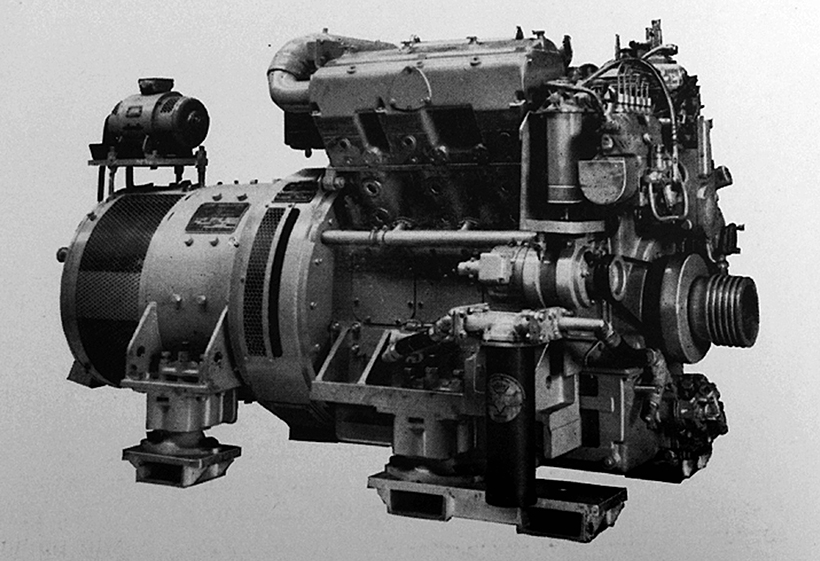

The motive power was a diesel V6 (60-degree angle) engine giving 275hp at 1,360rpm manufactured by Paxman of Colchester, driving through an RTB 7444 made by British Thompson-Houston Co, of Rugby.

A large part of my work with my firm Morrey Hire starting in 1961, was for Tarmac Construction Ltd among many other companies. My wife, Patricia, worked for Tarmac Ltd as a computer programmer from 1969, and then moved to Tarmac Construction in Wolverhampton as a systems analyst manager until 1979. She brought home a 75-year anniversary set of words and pictures of Tarmac Ltd, from which I used some of the photographs and wording.

For a money-saving subscription to Heritage Commercials magazine, simply click HERE