The first all-weather fire engines

Posted by Chris Graham on 19th August 2021

Ron Henderson discusses the belated introduction of the first, all-weather fire engines that protected crews from the weather and accidents.

A Jennings-bodied Fordson 7V appliance, showing the seating arrangement of a New World style of appliance. The arrangement prevented anyone from falling off, but it still left the crew exposed to the weather.

For many years, the standard arrangement of fire engine design was an open body, totally exposed to the elements, with the crew precariously positioned on a box behind the coachman. This ‘Braidwood’ design was carried over from horse-drawn manual and steam-operated fire engines. The introduction of self-propelled steam and petrol-driven machines offered a more efficient motive power, but the ‘Braidwood’ bodywork style (named after James Braidwood, Edinburgh’s first chief fire officer) was continued on the modern, petrol-driven machines.

Commercial transport operators and passenger carriers progressed their designs to provide covered accommodation for their loads and their drivers. Not so with the fire service. The notion of open-topped fire engines continued, much to the detriment of their crews. There were many incidents of fatalities and serious injury suffered by firemen thrown from their seats, or through accidents when the vehicles were proceeding to calls and, on top of this, the lack of protection caused many illnesses as crews were totally exposed to the elements.

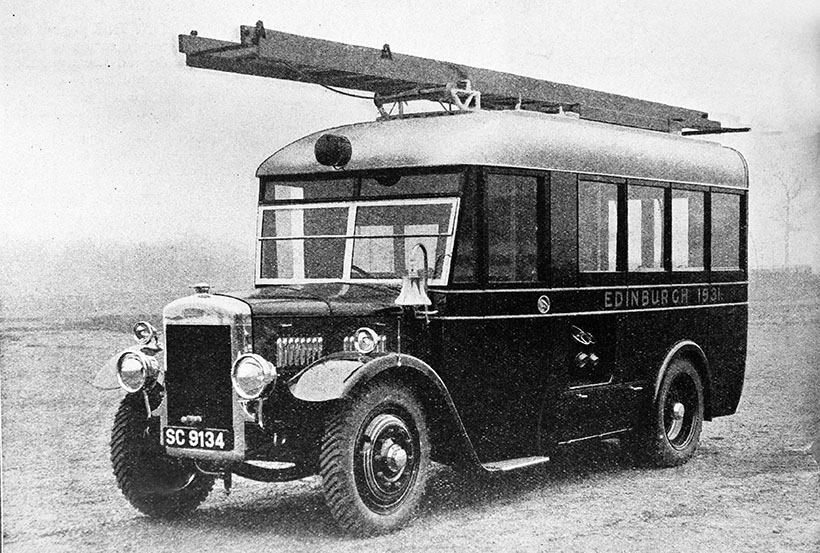

Edinburgh’s pioneering, 1931 limousine all-weather appliance, resembling a medium-sized bus. Based on an Albion six-cylinder, 90hp low-load chassis, the pump was mounted amidships, with access to the controls on both sides of the body.

Often, long-distance journeys of one hour or more were undertaken where the crews were exposed to low temperatures, rain and snow, and were then expected to get to work for many hours at a time, before making the lengthy return journey, then all of the used equipment had to be cleaned and replaced before any rest was allowed. Consequently, many firemen succumbed to various respiratory ailments, such as flu and pneumonia.

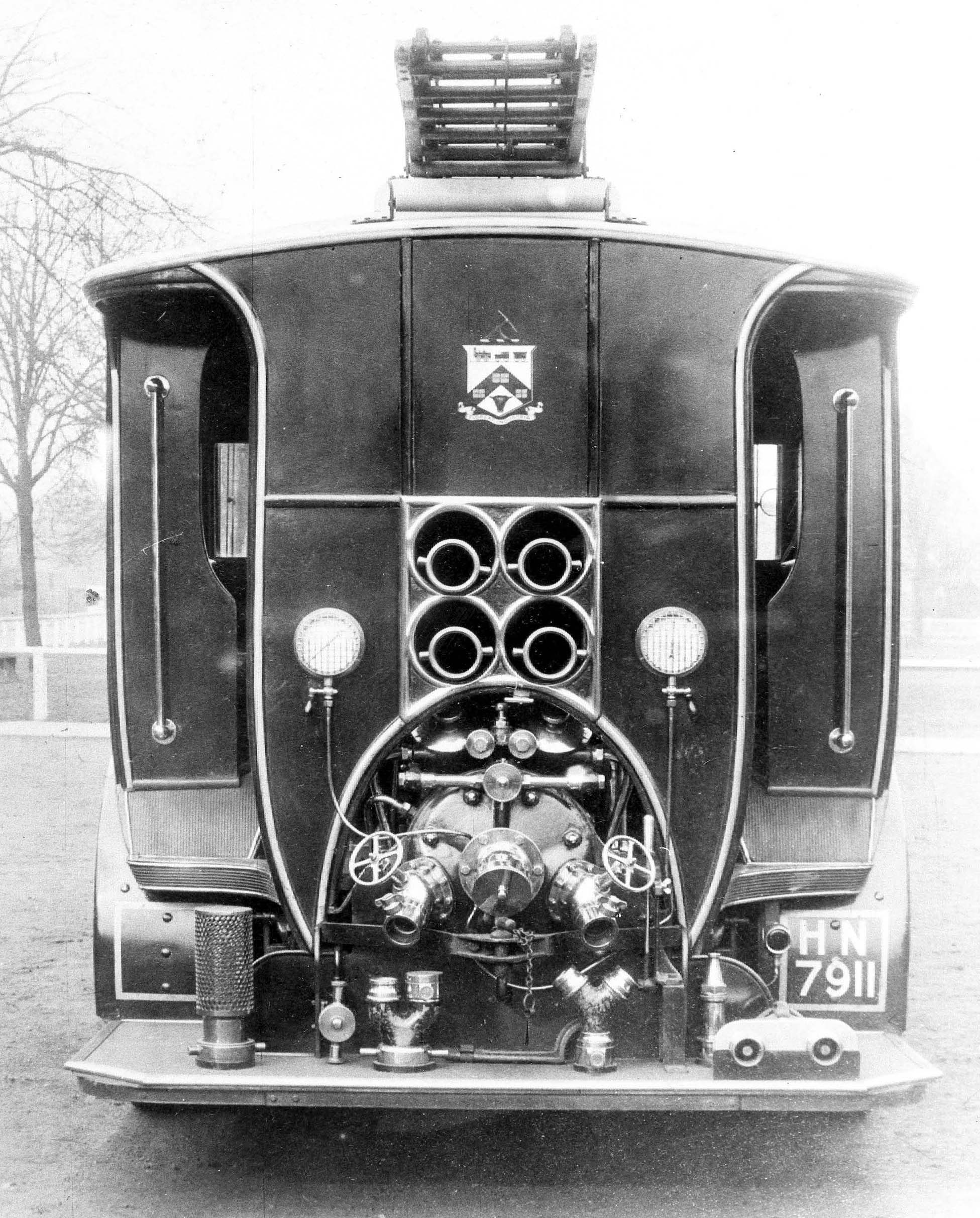

The unusual boarding platform arrangement of the Darlington limousine, where crew members could enter and exit from either side of the appliance. All the equipment was accessible from outside the appliance, thus not impeding the fire-fighting operations in any way.

The reason why fire brigades continued with open-topped vehicles was the ludicrous notion that boarding and exiting covered appliances would impede the turnout, and delay the initial performance on arrival at a fire. Also, because firemen were likely to get wet through at the end of their journey, there was no need to protect them from the weather on the way!

By the end of the 1920s, these problems finally started to be addressed with the gradual introduction of a ‘New World’ style of bodywork, first adopted by North American fire departments, where the crews sat facing inwards on benches inboard of the bodysides, but they were still exposed to the elements. Luton Fire Brigade had the accolade of introducing this style of bodywork into the UK.

Darlington had the distinction of being the first English fire brigade to commission a fully-enclosed limousine appliance. Fitted with a built-in pump, an additional trailer pump was added, for attending fires in rural parts of the brigade’s turnout area.

Ilford Fire Brigade produced the first British fire appliance to have an enclosed cab, when a 30hp Crossley general-purpose tender was commissioned in 1923 while, in the same year, the Paris Fire Regiment acquired a limousine pump which was the first, all-weather fire appliance in the world.

Eight years passed before a British fire brigade adopted the idea of improving working conditions for firemen. This occurred in Edinburgh, where the city’s fire brigade made the bold move of commissioning a fully-enclosed fire engine, in which the entire crew was afforded the unheard-of luxury of riding to and from fires in considerable comfort. The forward-thinking chief-officer: “did not believe in exposing crews to being flung off appliances, side-swiped, or severely injured in even a slight collision”.

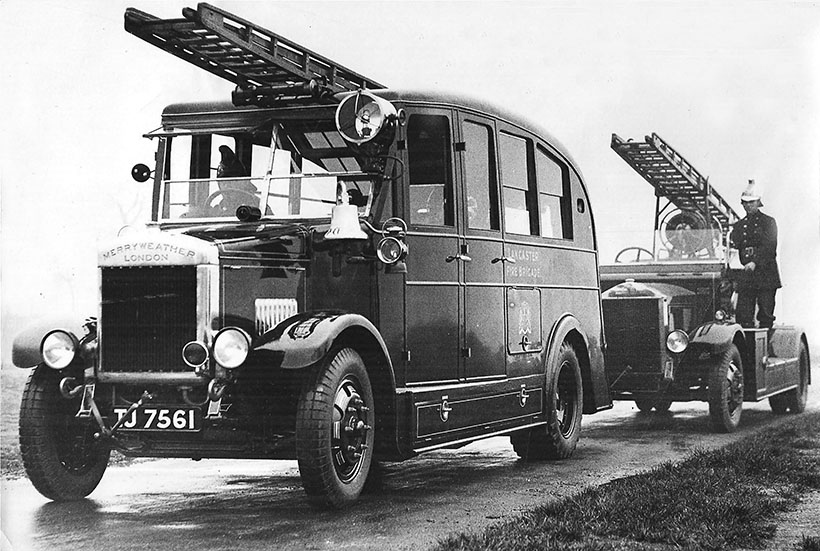

Seven years passed after the introduction of the UK’s first all-weather fire appliance, before the London Fire Brigade saw the light. Between 1935 and 1939, the brigade ordered a total of 34 ‘streamlined’ machines spread between Leyland, Dennis and Albion chassis, all with the same style of bodywork. This is one of four Merryweather Albions.

This pioneering machine was built on the lines of a medium-capacity bus, with a saloon-type body constructed by Merryweather & Sons, on a six-cylinder, 90hp Albion chassis. Almost simultaneously, over the border in England, the chief fire officer of Darlington Fire Brigade was also concerned about the cost of men placed on the sick list, and the reduction of manning levels during bad weather. So, with the welfare of the men in mind, this brigade became the first English authority to commission a fully enclosed, all-weather appliance.

Based on a Dennis Low-load chassis, with bodywork designed by Chief Fire Officer Spencer and constructed by local coachbuilder, J Higgins, the appliance had accommodation for up to 12 persons. According to the chief fire officer, the commissioning of this appliance would mean that the men: “will no longer arrive at the job numb and, as was sometimes the case, wet through with rain and sleet, and they will return to the station in comparative comfort.”

While open-topped fire appliances were virtually obsolete by the end of the war, occasional special circumstances, such as outdated fire stations designed to accommodate horse-drawn equipment, necessitated special arrangements, such as this 1960 Dennis F8 model for Wokingham, Berkshire.

However, the notion of all-weather appliances was slow to catch on. Some future designs incorporated enclosed cabs for the driver and officer in charge, but with the rest of the crew still being exposed to the open. Others offered a semi-enclosed appliance, but with open door apertures that would take seconds off the crews getting to work at a fire. Another variation was the cross-seat or transverse seating arrangement, where the crew seat was situated width-ways behind the driver; a much safer arrangement, but which still left the crews exposed.

But the diehards continued with open-topped appliances, and it wasn’t until 1935 that the London Fire Brigade bought its first all-enclosed, ‘streamlined’ appliance. This was based on a Dennis Lancet chassis, with bodywork designed by Chief Fire Officer, Major CCB Morris, who determined that if the appliance proved successful, no further motor pumps would be constructed without giving complete protection to the men when proceeding to and from a fire.

A 1934 Albion-based Merryweather Hatfield streamlined limousine motor pump for the Borough of Lancaster, showing the contrast between the comfort of travelling in this style and, behind, the open-topped style that was still the norm until World War II.

By 1939, when war was again declared, there were still many fire authorities sticking with the notion of open appliances and, even during the war, the mass orders for standard fire engines procured from the government featured batches of open-topped turntable ladder appliances, but the pumping appliances featured standard commercial vehicle cabs with prefabricated shelters for the crew.

After the war, the notion of open-topped appliances was finished, apart from some special orders for private, industrial brigades, export orders to warmer countries and the odd special order.

For a money-saving subscription to Vintage Roadscene magazine, simply click here