The versatile Thames 400E range

Posted by Chris Graham on 1st April 2021

Peter Simpson tells the story of Ford’s 1950s van, the versatile Thames 400E, which set new standards in a rapidly-changing market.

The versatile Thames 400E. Here’s a 1964 pick-up on the 2017 HCVS Sprat & Winkle Run. Owned by the Ellis family vehicle body-building business from new and stored when its working days were over, this vehicle is now being preserved by the next generation. (Pic: The late Jim King)

These days, many people think of the versatile Thames 400E as the van which, in 1965, Ford replaced with its radical new Transit and, in so doing, transformed the whole 15-35cwt van market. By comparison, the 400E seemed ancient.

That, though, isn’t really fair. Less than eight years earlier, in November 1957, the 400E was the smart new kid on the block, and itself represented a massive step forwards. Its predecessor, the E83W Fordson, dated back to 1938 and, with a sidevalve engine and transverse leaf springs front and rear, it wasn’t exactly state-of-the-art, even then!

Plain vans are now among the rarest of the 400E variants, despite probably being made in the greatest numbers, originally. This superbly-restored example is a regular prize-winner, but is also used to transport classic motorcycles, as the signwriting implies.

Looking the part!

The 400E, though, was slap-bang up-to-date in 1957. It looked the part but, more than that, it was the part! From important stuff like forward-control layout and a 180cu.ft payload capacity within an 84in wheelbase, to neat touches like the unique, semi-ribbon speedometer display, it was very new, very exciting and very, very Ford!

It went well, too – thanks to its modern, 1,703cc OHV engine. The 400E’s 60+mph top speed was, compared to its predecessor’s 40mph (with a following wind), warp-factor seven!

Customers took to it, immediately and, in less than eight years, Ford sold 187,000 of the 400E family. On a year-for-year average, that beats 370,000 Bedford CAs over 17 years from 1952 to 1969. But that’s an over-simplification, of course; the CA’s year-on-year sales rose and fell significantly during that time.

A very late Minibus in BOAC livery; you may just spot the unusual Ford brand name on the nose, instead of the more usual ‘Thames’.

The main point, though, is that the Thames 400E was right up there with it. The 1950s was a period of great change within the medium-size van market. In 1952, Bedford’s CA sent shock-waves through the entire market-sector. New layouts were needed to maximise loadspace within overall length. Driver convenience and comfort mattered too – albeit strictly in that order – and with increased loadspace came a demand for greater payloads. By 1960, 15cwt rather than 12cwt was the norm, and the race to 17cwt had begun.

Capacity matters

But payload capacity was at least as important as payload weight, and one has only to compare a typical, early 1950s, 12-15cwt van, such as the Trojan or Standard Vanguard, with the 180cu.ft 400E, to see what progress had been made. Even the Standard Atlas, despite being flawed in other ways, could take 180cu.ft. To catch up, Bedford offered a LWB CA from 1959 – though, at 162cu.ft, even this was smaller than the Ford.

Pick-ups were popular, but seem to survive in disproportionately high numbers today. There was a choice of steel bodywork from the factory, or wooden produced by outside bodybuilders.

What’s significant, though, is that the LWB CA became, effectively, the standard CA instantly; the SWB version, though still made, accounted for a minority of sales. Things had moved on and, although Bedford had started the revolution, Ford was now powering it.

BMC’s J2, introduced in 1956, was even bigger, at 200cu.ft, but as this was only sold with 15 and 16/18cwt weights it was, arguably, in a class above from the start. BMC certainly seemed to think so; hence the separate, smaller range (J4) from 1960, covering the 10-12cwt class.

In the late 1950s, Ford of Britain was also very different; it operated completely independently from Ford of Germany. Each had its own model range, which were totally different, even down to the Brits using imperial measurements and the Germans metric. While neither made much impact in the other’s home-market, anywhere else (including elsewhere in Europe) was open to both and, in many markets, completely different British and German Fords were direct competitors.

Campers were popular, too, of course; this Dormobile conversion has recently been restored to a very high standard by Peter Bridger.

Apparently, it was Henry Ford II himself who saw the absurdity of this, and got the two sides to work together, with the Transit being the first, pan-European Ford made – in broadly identical form – in Britain and Germany.

The 400E arrives

Anyway, the 400E was introduced in November 1957 (production having started in September) following, in classic Ford style, careful studies of all the rivals. The overall design was, unsurprisingly, stateside-inspired and forward-control with the engine under the cab – to maximise loadspace within the overall length.

Other campers were available; this one is by Calthorpe; note the trademark concertina-style elevating roof.

Unlike Bedford and BMC, however, the 400E had a separate chassis though, for ease of construction, on ‘closed back’ versions (with the van-type body) the cab and body were welded to the chassis outriggers, and there was no rear crossmember. Open-back 400Es, however, had outriggers designed so that bespoke bodywork could be bolted on, and the cab was also bolted on so it could be removed and/or modified. Unlike most of its rivals, the 400E was never offered with sliding cab doors.

Independent, coil-sprung wishbone suspension was used at the front; Macpherson struts were considered, but would have protruded too far into the cab. At the rear, a leaf-spring live axle was employed, but with two longitudinal springs rather than a single, transverse one. The 1,703cc, four-cylinder engine came, slightly modified, from the Ford Consul, along with the three-speed gearbox. At this stage, the Bedford CA came only with ‘three on the tree’. From June 1961, a diesel option (courtesy of the Perkins 4.99 engine) became available.

Until the mid-1960s, Ford of Britain and Ford of Europe existed as totally different entities, each with its own range of models that shared absolutely nothing. This, in pick-up form, is a Taunus Transit – the German Ford rival to the Thames 400E – of which 255,824 were made at the Cologne factory.

The ‘closed’ versions were factory-made as vans and a 12-seater minibuses which were, for taxation purposes, commercial vehicles. Eight- and 10-seater estate cars which were considered cars, so subject to Purchase Tax. But these were soon discontinued first time around, although reappeared later.

De-lux version

That, though, didn’t stop the Ford marketing operation swinging into gear with a de-luxe version, featuring chrome bumper overriders, side mouldings and window surrounds, plus a passenger-side external mirror. This was typical Ford; all very noticeable, but nothing that cost much to do or, in reality, mattered that much. Few de-luxe estate cars were sold.

We’re not aware of any surviving Powertruc 400E-based mobile compressors today, so here’s a Dinky model instead. Numerous 400E variants have been modelled over the years – vans were even used as a ‘wagon load’ by Tri-ang-Hornby model railways.

Special bodywork options were included in the sales brochures, and were built by approved suppliers. They ranged from pick-up-type dropside trucks (Ford offered an entirely in-house pick-up, with steel-sided body, from 1961), through ambulances, gown vans, mobile shops, milk floats to Luton-style vans, tower wagons and even a small refuse collection vehicle.

The most unusual application for the 400E chassis/cab, however, was as the Powertruc – a mobile compressor truck where, ingeniously, a Ford 592E diesel engine powered both a Hydrovane rotary compressor and the vehicle. These carried ‘Powertruc’ branding up front, instead of ‘Thames’.

A view from the rear. The forward-control layout was designed to maximise payload area within the overall length.

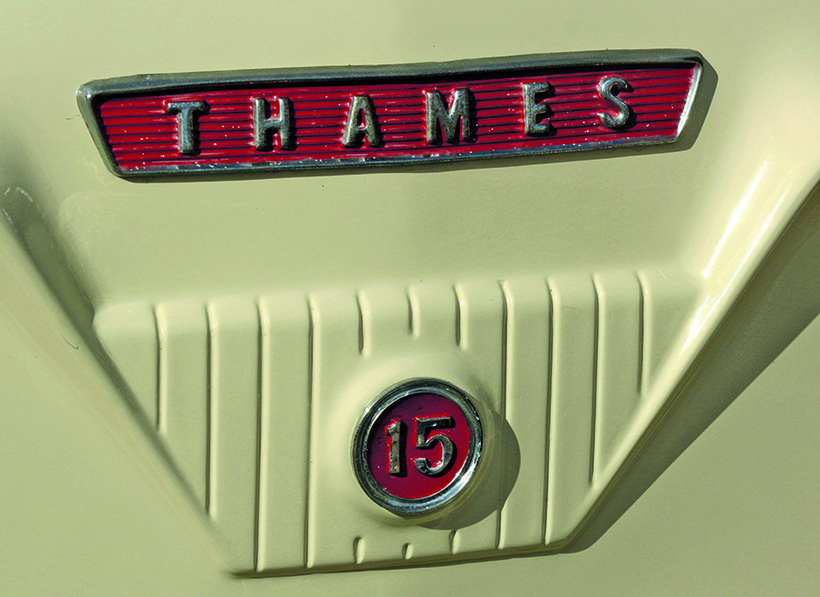

At this point, we probably ought to delve into make/model designations a little, as these can be confusing. First – and perhaps most important of all – most of the 400E family weren’t technically Fords at all, even though their manufacturer was never any secret. Until March 1965, all ‘Ford’ commercial vehicles were branded ‘Thames’ (in the same way that ‘Fordson’ had been used on pre-war commercials, and still was on tractors). It was only after the Thames Trader lorry was replaced by the D-Series, in 1965, that the Ford name was applied to light commercials. On the 400E range, however, this lasted just five months, before production ended in August.

What’s in a name?

Secondly, while the name ‘400E’ is often used to describe the whole range, strictly speaking, it applies only to the 10/12cwt chassis with petrol engines. The 15cwt vans, and 12-seat buses, were designated ‘402E’, and all vehicles with the Perkins diesel engines were ‘406Es’. At first, the ‘E’ number bformed part of the chassis number but, from November 1961, a new ‘Vehicle Number’ system was adopted.

Look carefully because this one isn’t quite what it seems at first glance. The 400E has always been popular with customisers…

There were also, of course, 400E caravanettes from all the usual suspects; Martin Walter, Cathorpe, Kenex, Airborne and Peter Pitt – and that’s by no means an exhaustive list. All officially-approved camper conversions were listed in Ford’s Holiday Adventures brochure.

Finally, and talking of Martin Walter, a 400E ‘Utilabrake’ was also offered. This was intended mainly for use by farmers and the like, and had windows in the back, plus a second row of padded seats. Behind these, there were short, inward-facing seats for occasional use only, as the back part was intended to carry goods most of the time. The Utilabrake was a good idea, but really it worked better with the wider, Bedford CA bodyshell.

Ford’s Dagenham and, subsequently, Langley (Slough) plants produced RHD and LHD versions of the 400E, and the latter was exported widely, including into mainland Europe where, as already noted, it competed with Ford of Germany’s Taunus van. Other major export markets included Commonwealth countries – CKD vans, minibuses and chassis-cab units went in significant numbers to Australia and New Zealand for local assembly, and assembled vehicles went to South Africa, Canada and, until 1962, America. Smaller numbers found their way to Asia and South America. In Denmark, where Ford had an assembly plant, there was a lengthened version, powered by the Ford Zephyr six-cylinder engine.

Cab access was good. A heater was optional, but is definitely a plus point for year-round use though, in summer, the engine alone can make the cab a little too hot…

Not much changed

Once launched, little was done to the 400E, in terms of development, and the only visible difference between the first in 1957 and the last in 1965, was that the badge proclaimed ‘Ford’ rather than ‘Thames’. Production had moved from Dagenham (hence the Thames name…) to Langley (Slough) in 1961, to free-up space for, among other things, the Cortina line. From January 1963, a slight mechanical upgrade had taken place, with the 1,703cc petrol engine gaining a little extra power (55hp low compression, 58bhp high) and a four-speed all-synchro gearbox as an option, though ‘three on the tree’ remained standard. A stronger back axle accompanied the four-speed ‘box. Just over a year earlier, Bedford had offered a four-speed option on the CA.

In truth, these changes were as much about the Mk2 Consul having been replaced by the MkIII Zephyr 4, and the more powerful engines being what was being made, than any desire to improve the 400E. The four-speed ‘box, too, had been introduced for the Zephyr 4. Work on the Common Van (aka Transit) project had started in 1960 and, with lots happening on the car side too, it’s probably hardly surprising that the 400E – which was selling well anyway – was left largely to its own devices.

Buyers were a mixed bag of fleets, small companies and ‘sole traders’. Some went to public utilities, including regional gas and electricity boards. National fleets known to have used them included Whitbread Breweries, Currys, Weetabix and various parts of the Rank organisation. However, Britain’s biggest single fleet buyer of vans – the GPO – only ever had six. Three were Powertruc compressors, two were diesel mailvans and the last was a petrol Telephones Utility van on trial.

A ribbon-type speedmeter is bound to bring back a few memories; I’m pretty sure this was unique to the 400E.

Curiously though, Oxford Diecast have produced models of the single Telephone and Royal Mail demonstrators. The final one is something of a mystery; in 1966 the Telephone Manager Brighton bought, very unusually, a used 1961 400E from Brighton Corporation which, despite the change of ownership, retained Brighton’s dark blue livery.

Secondhand scene

Though production ended in 1965, many 400Es remained in regular, revenue-earning service right up to the late 1970s. Many smaller concerns who bought a 400E new, hung on to them – especially if they’d been used on light duties – and ex-fleet examples found new homes with tradesmen and small business owners who appreciated the compact dimensions and high capacity, simple mechanical layout, good driving manners and excellent parts availability.

The chassis construction also enabled many to be ‘modified’ for specialist purposes, such as breakdown recovery or as car transporters; many a 400E chassis was extended in ways which would be frowned upon today! A lot were also bought for ‘non-commercial’ purposes, such as motorcycle transport and, of course, homemade camper conversions. Many a scout troop spent years holding jumble sales and collecting waste paper to buy a secondhand 400E minibus which, being based on standard Ford car components, could also be used to teach basic vehicle mechanics.

Nose-branding identified payload. Until 1965, the brand was ‘Thames’, not ‘Ford’.

As usual with old vans, though, there were also aspects which are recalled with rather less rose-tinted pleasure. One was the vacuum-operated wipers, which slowed right down when the engine was pulling hard – which was often when they were needed most! The gear linkage also wore as it aged, leading to imprecise changes and, not infrequently, locking-up mid-change. Freeing this usually meant crawling underneath and ‘adjusting’ with a hammer. I also recall unladen 400Es being slightly unstable when cornering in wet weather and/or a strong and gusty sidewind.

Where have they gone?

Until the late 1970s, 400E were still a fairly common sight. By 1980, though, they all seemed to have disappeared. Natural aging was clearly a consideration, and some parts availability issues were emerging. The main killer, though, was probably a significant tightening of the MoT at the end of 1977. It seems incredible now but, until then, structural repair sections didn’t have to be welded; they could be brazed, or even pop-rivetted! So, many past MoT patch-ups had to be reworked to get through a test, and that simply wasn’t cost-effective.

A number did live-on in a different form, though. The mini-yank looks made them ideal vehicles for customising, and the separate chassis carrying all the structural loads made radical bodywork mods easier. A detachable cab that could be raised a few inches, also opened-up lots of bigger engine possibilities.

Today, the whole 400E range is highly collectable and, although the plain vans were made in the greatest numbers, they’re now one of the rarer types. The Ford 400E Owners Club caters for them, and provides many member services, including a regular club magazine Thamesline, technical advice, access to club and other spare parts sources, and access to historic records. It also attends events as a club. To find out more, go to ford400eownersclub.co.uk, email thames@btinternet.com or write, enclosing an SAE, to The Ford 400E Club, c/o Sandy Glen, 1 Maltings Farm Cottages, Witham Road, White Notley, Witham, Essex CM8 1SE.

For a money-saving subscription to Classic & Vintage Commercials magazine, simply click here