1900 hot-air engine runs once again

Posted by Chris Graham on 10th February 2023

Barry Job reports on the exciting firing and running of an amazing hot-air engine that’s over 120 years old.

Hot-air engine: The Hayward Tyler engine with Malcolm Rigby on the left and Alan Williamson on the right.

In a secluded Staffordshire barn is stored a Hayward Tyler hot-air engine. The serial number of 772 gives a construction date of about 1900, quite late for these engines.

The operating principle of these engines is credited to the Scottish clergyman and engineer, Reverend Robert Stirling, who registered the patent in 1816. Within two years he had developed the first practical hot-air engine which was remarkable as he was not an experienced engineer, and the first treatise on thermodynamics by Sadi Carnot – the theory on which all heat engines worked – wasn’t published until 1824. In his honour the hot-air engine has now become popularly known as the Stirling engine.

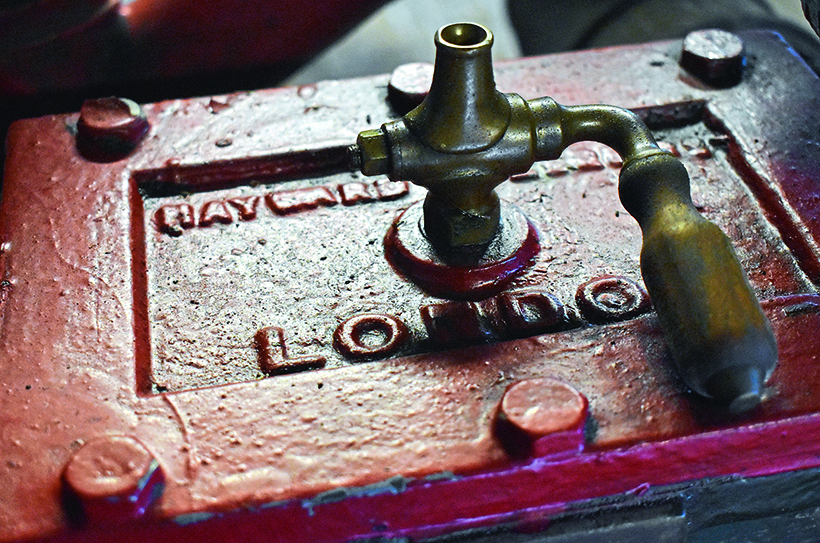

The Rider’s patent plate.

It was developed in America by Captain John Ericsson, born in Sweden in 1803, he had developed a single-cylinder hot-air engine by 1820. His engines were built at the Phoenix Foundry, New York. In 1838 Alexander Rider was in charge of the foundry, and he developed Ericsson’s engine into one with two cylinders. In England the ‘Improved Rider Ericsson Hot-Air Engine’ was built under license by Hayward Tyler of Luton. At first sight these engines may be confused with steam engines as they utilise an external fire and water to develop power, but there the similarity ends.

Victorian period

They became quite popular during the Victorian period, certainly steam engines were being developed then, but there was concern over the large quantity of coal consumed by their boilers; there was a great fear of boiler explosions and consequently insurance companies frowned on them. The hot-air engine, which can operate on a small quantity of any fuel, is quiet and there is no risk of catastrophic explosion. The design works on a closed cycle where the same air is used over and over again. There are two cylinders, each with its own piston.

The serial Number 772.

The ‘power’ cylinder is heated by an external fire, the pistons, driven by cranks on the flywheel, are about 90 degrees out of phase with one another, so air is drawn out of the ‘power’ cylinder, through a regenerator to the ‘compression’ cylinder. The regenerator consists of thin metal plates and the efficiency of the engine is due to the regenerator; it is this which rendered the hot-air engine a rival to the early steam engines. As the air passes through the regenerator heat is transferred to these plates. The ‘compression’ cylinder is jacketed with cold water so the air is quickly cooled and then passed back to the ‘power’ cylinder picking up heat from the regenerator as it does so. The fire creates more heat, and so the process is repeated. Thus power is derived from the expansion of the air in the hot ‘power’ cylinder and its contraction in the cold ‘compression’ cylinder.

Weight-to-power ratio

In spite of its size and weight of about one ton, this Hayward Tyler engine is only rated at half a horsepower; this is cast into the flywheel. Its advantage is that it is simple to use and does not need an engineer to operate it. The hot-air engine was intended to be supervised by a gardener or estate worker, indeed it was said to be ‘so simple even your kitchen maid can operate one.’

Pete Massey lights the fire under the ‘power’ cylinder.

The heyday of the hot-air engine was about 1890; thereafter safer steam boilers, improving internal combustion engines, and then the introduction of electrical power saw their rapid demise. One company to continue with the hot-air concept was the Dutch technology giant Philips of Eindhoven who were keen to market its radio sets into parts of the world where electric mains power and batteries were unavailable. In 1950 they developed a high-speed Stirling-engined generator to power the valve radio sets of the time, but as transistor radios were coming to the market this return was short-lived.

However, the concept is not dead. A recent resurgence has now occurred. The reuse of the same air makes them ideal for application in satellites where magnified sun’s rays provide the heat source. Their lack of noise and vibration makes them the engines of choice for Sweden’s submarines and they are also used to provide the cooling for the magnets in MRI scanners.

Trevor Williamson pulls on the flywheel to set the engine in motion.

Engine No 772

Engine number 772 was acquired, in pieces, by the current owner 50 years ago from Twemlow Hall in Cheshire. It had been used to pump water from a spring up to the ‘big house’, a surprisingly small external vertical pump being connected to the ‘compression’ cylinder piston. This was a typical application for these engines; it had been replaced by an electric motor and pump. The engine was reassembled, a water tank bought at a nearby farm sale, a local carpenter constructed the wooden base and new leather seals acquired and fitted. Once painted it was ready for display but it rarely went to shows. Thus Malcolm Rigby, the owner, and Alan Williamson, the custodian, thought it appropriate to celebrate the 50th anniversary of its acquisition by having it running.

The Hayward Tyler name plate.

Of course it was stored at the furthest corner of the barn; so Trevor Williamson and Pete Massey set to and quickly extricated it from behind the numerous artefacts which had collected in front of it. A journey with a fork-lift truck transferred the engine to a more convenient location for running. With bearings lubricated, cold water added and a fire lit, it was a question of waiting. It had been many years since it had last run, the leather seals had undoubtedly dried out, so would it go now? Yes, energetic pulling on the flywheel saw it come to life (but only just!). It then ran slowly for quite some time. The seals had been drenched in oil, no doubt this had soaked in so a second run next day saw it run better, at perhaps half its rated speed. The whole operation was deemed a great success. With the fire dead and the water drained, it was then returned to its slumbers in the barn once more.

This feature comes from the latest issue of Stationary Engine, and you can benefit from a money-saving subscription to this magazine simply by clicking HERE

Previous Post

Ultra-rare 1984 Simca van – the last UK survivor!

Next Post

World record 1904 Napier 15hp sale!