County class ships of the Royal Navy

Posted by Chris Graham on 19th October 2022

Conrad Waters provides a photographic review of the Royal Navy’s famous County class ships, an impressive heavy cruiser design.

County class ships: HMS Cornwall running trials from Devonport in October 1927, showing the initial design of the seven Kent class County variants. The high freeboard adopted by the ships is immediately apparent, but the lower funnels of the original configuration give a much lower profile than that typically associated with the class. This arrangement gave significant problems, such as smoke interference with important control positions, and the funnels were subsequently raised by 15ft – but by 18ft in the two Australian ships – to deal with the issue. (Abrahams courtesy World Ship Society)

The Royal Navy’s series of County class cruisers were built as a direct result of the Washington Naval Treaty that was signed between the major maritime powers in 1922. Aimed at preventing a new naval arms race similar to the one that preceded World War I, the treaty all but ended the construction of new capital ships over the following decade. An unexpected – and perverse – consequence of the new restrictions was a renewed focus on cruiser construction, the most powerful type that could now be built under the treaty’s restrictions.

Cumberland off the British Naval station at Wei-hai-wei in Northern China in 1929. One of the Kent class, she provides a good representation of the ships during their early operational lives. The four twin 8in Mk.I mountings in A, B, X and Y positions were capable of 70 degrees elevation for use in the anti-aircraft role, a mission somewhat beyond the capabilities of their fire control arrangements. Also visible are the unshielded single 4-inch secondary guns and 21-inch torpedo tubes aft of the third funnel. Although a platform for an aircraft catapult is present, the relevant equipment was not fitted until it became clear this could be installed within the 10,000-ton treaty limitation. (All images Author’s Collection unless stated)

The new ‘treaty cruisers’ were limited to a standard displacement of 10,000 tons and a main armament of 8-inch (203mm) calibre guns. Unsurprisingly, all the treaty signatories decided to build new ships that fully utilised these thresholds. However, designing such cruisers proved more challenging than expected. Different navies adopted various compromises with respect to areas such as armour, seakeeping and propulsion as they struggled to produce acceptable designs.

Shropshire was one of the quartet of London class Counties ordered under the 1925 naval construction programme. All were completed during 1929. Compared with the preceding Kents, they adopted a revised hull form intended to provide a modest uplift in speed. There were also slight modifications to the armour scheme and, more significantly, the provision of full aircraft arrangements from build. Shropshire finished her career in the Royal Australian Navy, being transferred as a replacement for the lost Canberra in mid-1943.

Wartime experience

Utilising the vast practical experience it had gained during the Great War, the Royal Navy’s design approach was arguably more effective than most. Encompassing eight 8-inch guns in four dual-purpose twin turrets, its new ships had good speed and a large, weatherly hull for effective operation along the British Empire’s all-important trade routes.

The County class were subject to a major programme of mid-life modernisation from the mid-1930s onwards. The five British members of the Kent class were the first to be upgraded, gaining much-improved side protection, increased secondary and close-range armament and – in all but Kent herself – a new fixed catapult and aircraft hangar. The torpedo tubes were removed and – in some ships – the quarterdeck cut down by a level to provide weight compensation. This 1938 post-refit photograph of Cumberland provides an interesting comparison with the 1929 illustration, which was taken in almost the same location.

Probably reflecting the experience of Jutland, magazine spaces were protected by heavily armoured internal boxes. The main area of compromise was protection for other areas, such as the machinery spaces, which received only limited armour.

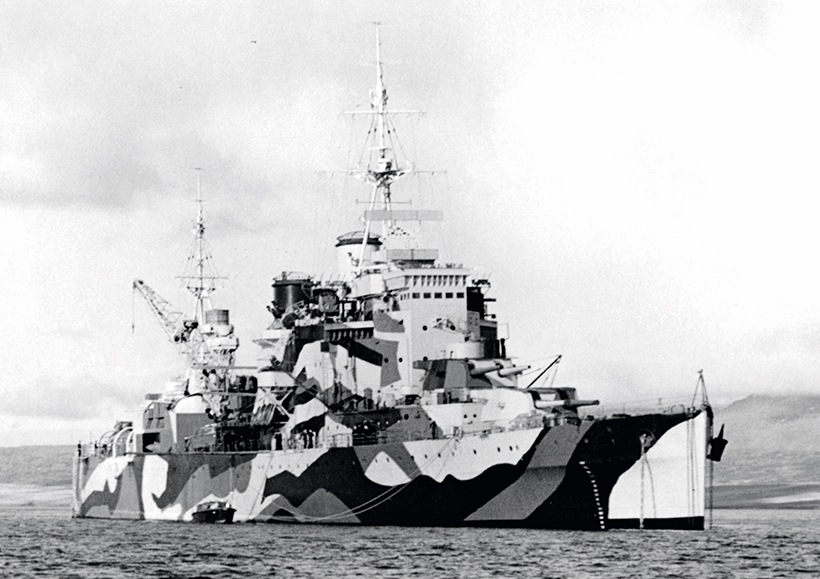

London in Admiralty Disruptive Camouflage at Scapa Flow, probably in 1941. The modernisation scheme proposed for the four London class Counties was far more extensive than that for the earlier ships, radically changing their appearance to something similar to the contemporary Fiji class cruisers. However, the outbreak of World War II cut short the scheme, with only London receiving an incomplete version of the planned rebuild.

Once the design process was concluded, orders flowed relatively quickly. Five ships of the initial Kent class were approved under the 1924 construction programme, a number boosted to seven by an Australian order for an additional pair. They were rapidly followed by four London class cruisers, authorised in 1925, and two Norfolk class variants in 1926; both classes incorporating incremental improvements over their predecessors. The combined total of 13 County class ships represented the largest Royal Navy cruiser series of the inter-war years.

Although Suffolk was to enjoy one of the most distinguished careers of all the County class cruisers, her wartime service was almost prematurely ended when she suffered severe attacks from German bombers off the Norwegian Coast in April 1940. A direct hit just forward of X turret put the aft engine room out of action and brought the ship’s quarterdeck underwater. This photograph shows the crippled cruiser on her return to Scapa Flow.

The County class’s main weakness was, arguably, their cost. This amounted to around £2.1 million a ship, around twice that of the smaller D class light cruisers armed with 6-inch guns. This became a growing problem as the Admiralty struggled to afford the large numbers of cruisers it required against a backdrop of declining naval spending. After briefly turning its attention to smaller 8-inch cruisers – York and Exeter – the Royal Navy reverted to ordering cheaper, 6-inch cruisers in a ‘quantity over quality’ approach.

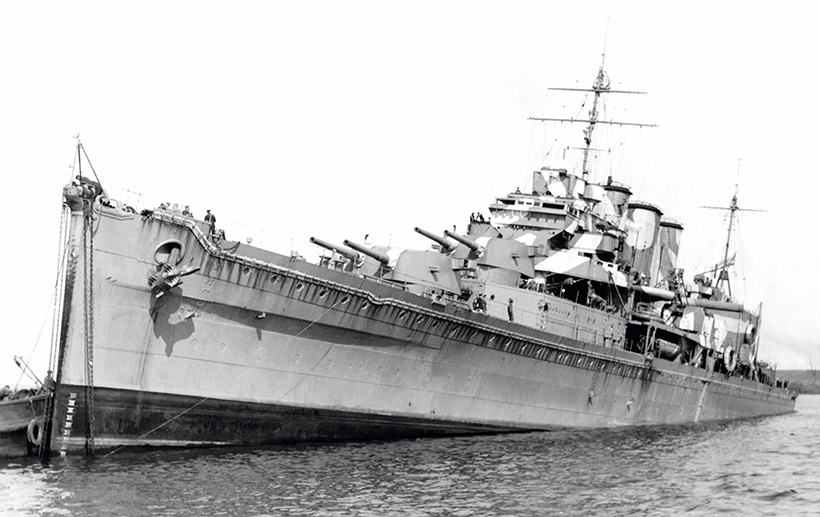

This photograph of Norfolk off Portsmouth in June 1943 illustrates some of the detailed enhancements typically applied to the class during the wartime years, most notably the installation of a comprehensive suite of radar equipment and significant upgrades to the close-range armament. Norfolk was, perhaps, the most famous of all the Counties. She was involved in the Bismarck chase from start to finish, and scored a hit that put the doomed battlecruiser Scharnhorst’s forward radar out of action during the Battle of the North Cape in December 1943. (Admiralty)

Nevertheless, the Counties remained an essential part of the fleet. A major programme of mid-life modernisation from the mid-1930s onwards saw significant improvements to the five Royal Navy Kent class vessels and a more radical reconstruction of London. The outbreak of World War II prevented the other ships from being rebuilt.

The need to improve anti-aircraft protection – alongside a diminishing surface threat – saw many of the Counties surrender X turret towards the end of World War II to allow more close-range weaponry to be installed. This 1945 view of Sussex is therefore typical of the class’s final wartime configuration, with large numbers of multiple pom-poms and small-calibre guns dominating the superstructure. Sussex was slightly damaged by a Japanese kamikaze attack off Malaya in July 1945, vividly demonstrating the importance of these enhancements. (Admiralty)

As the Royal Navy’s most heavily armed cruisers, the Counties played an important role in the conflict. Their size and endurance made them well suited for protecting the shipping routes, where the sinkings of the German raiders Atlantis and Pinguin were among their successes. The interception and destruction of the battleship Bismarck would not have been possible without the effective tracking performed by Norfolk and Suffolk. Norfolk also played an important part in the sinking of the battlecruiser Scharnhorst.

The Royal Australian Navy’s Australia was one of the longest-serving ‘Counties’, enjoying a lengthy post-war career that only ended with her final decommissioning in August 1954. She subsequently made the long voyage back to the United Kingdom, being broken up at Barrow-in-Furness. This photograph shows her in Sydney Harbour early in 1951.

Three Counties were lost in the conflict, all to the Japanese. Cornwall and Dorsetshire were overwhelmed by Japanese carrier aircraft during an Indian Ocean raid in April 1942. The Australian Canberra was scuttled after sustaining heavy damage the following August in the battle of Savo Island.

HMS Cumberland was the last ‘County’ class cruiser to remain in service, operating as a specialised trials ship to test new weapons and other equipment. This included the new 6-inch and 3-inch gun mountings intended for the new Tiger class cruisers. This picture shows her laid up at Devonport in 1959 after she had been decommissioned for the final time. She made her final voyage to the shipbreakers later that same year.

The surviving ships were close to the end of their design lives at the end of hostilities and most had made the final voyage to the scrapyard by 1950. However, Australia and Shropshire – the latter transferred to the Royal Australian Navy as a replacement for Canberra – survived into the mid-1950s. Among the Royal Navy ships, Devonshire served as a cadet training ship until 1954, while Cumberland also enjoyed a second career as a specialised trials cruiser. It was not until the end of the decade that she finally decommissioned, bringing the class’s illustrious 30-year career to a close.

The Spanish Navy built two heavy cruisers to a modified County class design at the then British-owned Ferrol shipyard between 1928 and 1936. One – Baleares – was lost during the Spanish Civil War, but the other, Canarias, went on to have a lengthy career, being scrapped in 1977. This 1967 photograph shows the clear resemblance of the Spanish ships to the Royal Navy’s design.

This feature comes from the latest issue of Ships Monthly, and you can get a money-saving subscription to this magazine simply by clicking HERE