Disastrous world water speed record attempt

Posted by Chris Graham on 4th February 2022

Author Steve Holter tells the story of John Cobb’s ultimately fatal attempt on the World Water Speed record some seventy years ago.

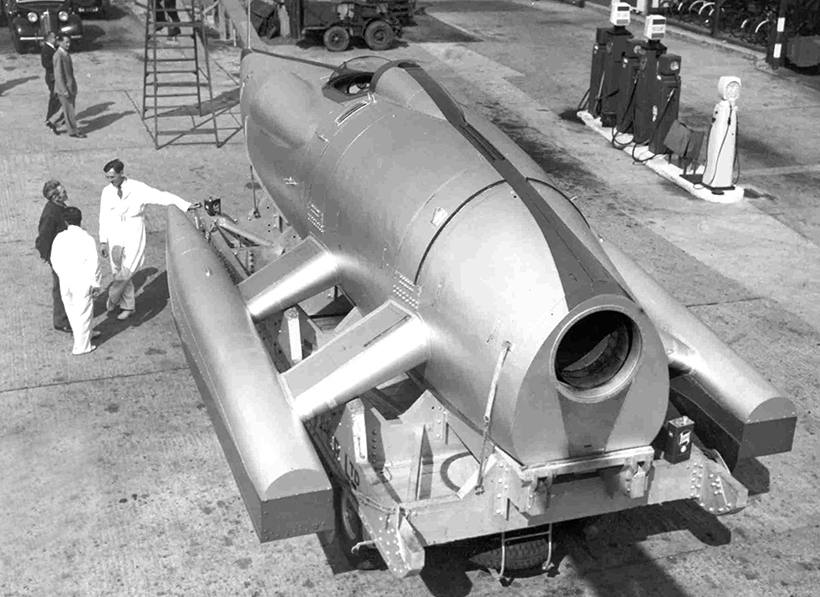

World water speed record: Cobb’s Crusader looked the part, but was full of faults underneath the skin, unfortunately. It’s seen here on the press day at Adams Transport, New Malden. (Pic: Getty Images/Hulton Archive)

Three hundred miles an hour is fast! In an aeroplane, it could be described as quite mundane. In a car, it’s a speed few get to experience, but in a boat? The fact that only one man has exceeded this speed, and lived, tells you all you need to know. Ken Warby set his world water speed record in 1978, peaking at 345mph, and averaging 317.59mph, and this in a wooden boat, with a jet engine, hand built by Warby in his back garden.

But in 1948, some 30 years earlier, two men were looking at exceeding 250mph, and secretly hoping for 300mph, in a boat built of wood, and powered by a jet engine.

The duo of John Rhodes Cobb, a wealthy fur broker, and Reid Anthony Railton had been cemented by none other than John Godfrey Parry Thomas. Railton had learnt much at the side of the innovative Welshman, and when Thomas moved to Brooklands to engage in the development of his Leyland Eight car, and ultimately the land speed record in his 27-litre Babs, Railton followed. It was at Brooklands the friendship between Cobb and Railton was founded. Cobb became Thomas’ unofficial backer, in exchange for the odd race in Babs, and on the death of Thomas at Pendine Sands in 1927, it fell to Cobb and Railton to continue the pursuit of speed.

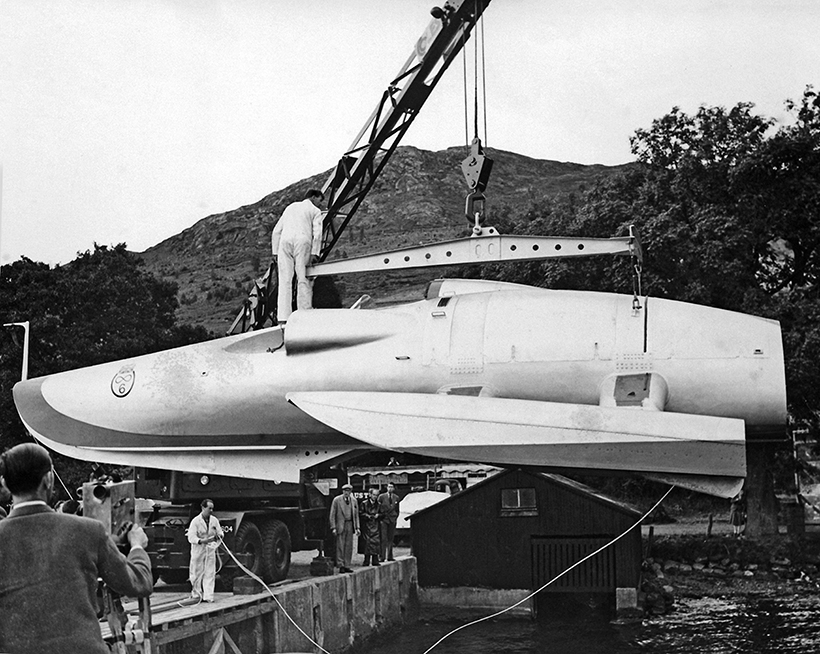

Loaded in the water as John Cobb gets ready to test the boat at Loch Ness. (Pic:John Bennetts, courtesy Julie Newton)

By 1948, John Cobb already held the land speed record of 394.2mph in a revolutionary twin aero-engined car called the Railton Mobil Special designed by Reid Railton, but a lack of competition had Cobb looking for a new challenge, and he decided on following the same route as Henry Segrave and Malcolm Campbell before him, by taking to the water.

The water speed record is not something taken on lightly. Unlike high speeds in a car, on water, the surface is constantly changing. A high speed car fights mainly only aerodynamic drag, whereas a boat has two fronts to combat, aerodynamics and hydrodynamics, so Cobb would again have to rely on the design genius of his old friend Reid Railton.

The concept Railton proposed to take the water speed record was like nothing previously seen, but was arrived at by simple, logical development from his previous work on Sir Malcolm Campbell’s Blue Bird K3 and K4 hydroplanes. However, in post war Britain, it was difficult to get anyone to accept the task of constructing something unconventional, especially when materials were still in such short supply. Eventually Vosper took on the responsibility to turn Railton’s thinking into the functioning craft that was to be called Crusader.

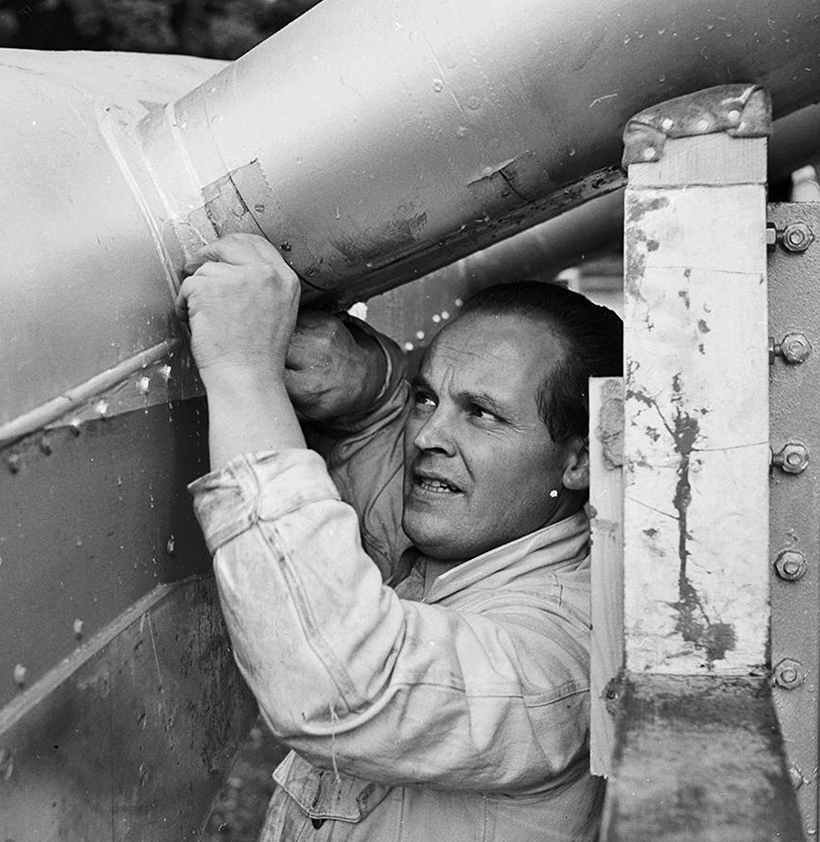

Harry Cole gives scale to Crusader, there are three lifting points on the hull; two on the rearward alloy hoop and one forward of the cockpit. (Pic: John Bennetts, courtesy Julie Newton)

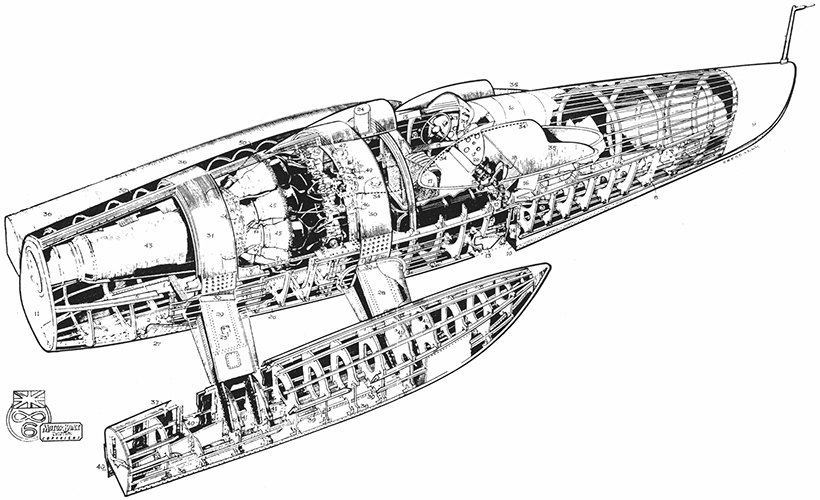

After a long and troubled design and research process, construction began. The main hull was built mostly from birch plywood bulkheads, cut from single sheets for strength and attached to an internal wooden keel, which was made in several parts. The un-skinned hull resembled a massive model boat, though this was covered by an outer skin of 1/16th ply sheets cross-laid onto spruce stringers, and finally covered with ‘doped’ fabric and then highly polished, producing a type of wooden monocoque. For all highly stressed internal members, such as the engine mounting and supports for the rear sponsons, aluminium alloy was formed into two ring bulkheads, but here the construction differed from Railton’s vision, as he had proposed a third ring ahead of the cockpit, to support the forward planing shoe, mount the rudder and with horizontal connections, protect the pilot while increasing general hull strength. Neither the third ring nor the horizontal elements were included in the build.

Cobb financed the build himself, giving Vosper a cheque for £15,000 (roughly £500,000 in today’s values), though the project cost him nearer £45,000 (£1.5 million) in total.

The team arrived in the highlands of Scotland in late August 1952. The project manager was Cobb’s friend and land speed rival, George Eyston, who had strong links with the Castrol oil company. He had organised for the team to use the jetty and boat house of Alec Menzies at Temple Pier, Loch Ness, and it was here that the men from Vosper, engine supplier De Havilland, and radio experts PYE set about preparing Crusader for her first run.

This took place on September 3, with Vosper’s Peter du Cane, who had overseen the research and construction of Crusader at her helm, as Cobb had a meeting in Inverness.

Hughie Jones struggles to check that the sponson mounting bolts are still tight after a run. (Pic: Getty Images/Ray Kleboe)

Du Cane achieved a speed of about 100mph, and noted that the boat was hard to turn at low speed, but also had a tendency to hold her speed on a closed throttle, which had been noticed during the model testing stages. As Crusader was about to be lifted out of the water, Cobb returned, and wasted no time in taking the controls himself. Surprisingly, not only was this the first time he had sat in the cockpit of the boat he had paid for but it would be the first time he had piloted a boat at more than 40mph. The record he was aiming for was in excess of 171mph!

Cobb made five runs, all at around 100mph, successfully turning at the end of each run, and over the following days, when the weather allowed, he continued to increase his speeds, while attempting to iron out any problems that arose. Of these, one was of major concern, the strength of the forward planing surface. Up until this time, the fastest, most up-to-date water speed record challengers were of the “three point” design, with a single stern planing surface and two forward planing surfaces, separated by a concave bottom to the hull, so that at speed the craft was only touching the water on these three points.

What Railton had done was to reverse the layout, moving the single planing surface to the front, simplifying the installation of the Ghost jet engine, but increasing the loads on the single forward surface, where the third alloy bulkhead should have been. From the first runs, this forward surface was showing signs of distorting, to the point where the smallest members of the team were sent into the hull armed with strips of wood and screws, to try and reinforce it. What wasn’t known to many of the team were the changes that had been made to the design during the construction of Crusader that had compromised the hull’s integrity. Added to this, and against the wishes of both Cobb and Railton, Vosper fitted a larger, heavier and untried rudder.

As the sun rises, Crusader is towed out by the ‘jolly boat’ to test the rope theory. (Pic: Private collection)

The entire process of design, research and construction had proved to be a power struggle between those who had conceived and paid for Crusader, and those charged with her construction, exacerbated by post war material shortages, convoluted trans-Atlantic communication (Railton was living and working in California), and the conservative construction techniques being employed, all of which were coming home to roost.

Railton insisted on planning meetings before each run and debriefings after, but a meeting of September 12 concentrated on the structural issues facing Crusader. At the time the meeting was recorded as being “high powered,” but could better be described as fraught and tense.

There have since been claims and counter claims, that letters were written and signed promising that the craft was capable, that the speeds would be held back, and that Cobb was retiring after the attempt and pushing toward his last record, but none of this can be substantiated. What can be accurately stated is that Cobb was told Crusader could take the record, in perfect conditions, but that Railton had to head back to the US on business and would return the following month for a record attempt. In the meantime, only high speed tests would be conducted.

John Cobb in full regalia, with self-inflating life jacket and leather helmet with radio headset.

(Pic: National Motor Museum)

Cobb, sympathetic to the religious beliefs of his hosts, had promised never to run on a Sunday, even though to date Sundays had offered the best conditions. Railton duly departed Loch Ness on Sunday September 28 to make his way south to Southampton to travel to America. Early the next morning, preparations began for a high speed test run.

To the public, the Crusader project looked no different to any previous record attempt; brave men, fast boats and a supporting team of boffins and engineers. But behind the scenes at Loch Ness, the personality clashes, errors of judgement and obscure engineering and design decisions had created the perfect scenario for disaster, and by 05:30, September 29 1952, the scene was beginning to be set.

The team had been on standby since 4.00am to try and take advantage of the calm early morning waters, but the smaller support craft returned from their exploratory course run to report that the water conditions at the far end of the measured mile weren’t suitable. As a result the motor yacht that was meant to have stayed in position at the half-mile mark, for timing and the press, returned to Temple Pier just at the time the water conditions settled down to allow a perfect run. The balance of getting back to position as quickly as possible while allowing time for the wakes left by all these craft to die down put Cobb under needless pressure. Added to this, the roads around Loch Ness were blocked by thousands of spectators that had positioned themselves to watch Crusader along her course, even though no record attempt had been announced.

Crusader in the flat and calm water that was needed for the record run, but which made getting onto the hull’s plane more difficult. (Pic: Author’s collection)

Cobb was a reserved character and happiest away from crowds but he was also grateful for the support shown, and now felt pressure to “put on a show” for those that had turned up to see him make a run, regardless of water conditions.

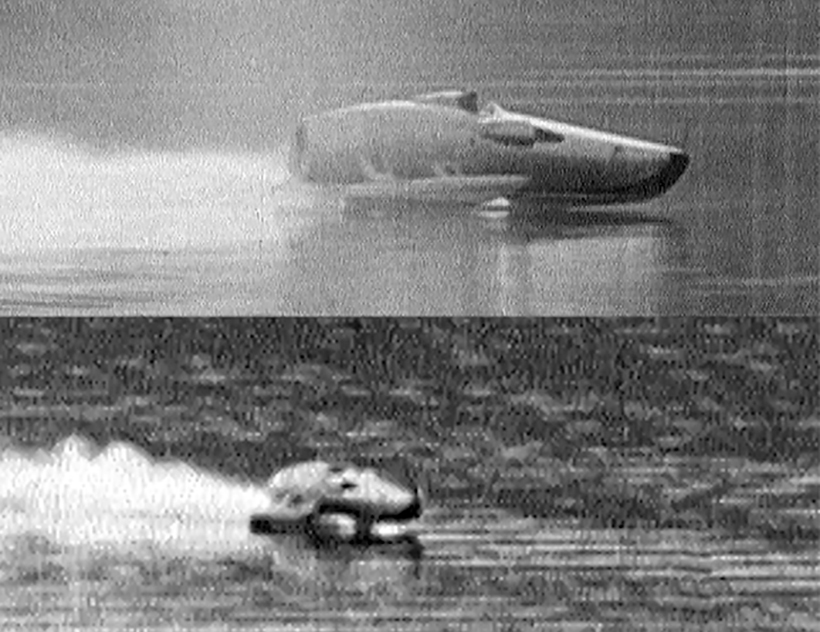

By 11:15, Cobb was aboard Crusader, and running through the warm up procedure for the Ghost engine. At 11:49, he accelerated hard toward the measured mile. Crusader quickly got up onto her planing shoes, and having started further away from the measured mile than on previous runs, Cobb worked up to a speed that was very much faster than ever before – in the region of 240mph.

As he approached the measured mile it soon became obvious all was not well. Witnesses report seeing Crusader bouncing and vibrating, unable to maintain her stable planing attitude. Then, just as Crusader entered the measured mile, three waves were seen traveling out from the northern shore directly across her path.

The first was struck with what witnesses described as a “pistol-like crack.” The engine note dropped, indicating a brief reduction in throttle, before rising again. But Crusader now started to rock from sponson to sponson. On hitting the second wave, the bow lifted noticeably before dropping back down just as Crusader’s stern hit the third and final wave, tipping in the bow. The instant the bow dug in, Crusader seemed to disintegrated into a vast plume of spray and debris. There was a shout of “He’s over.” Then silence.

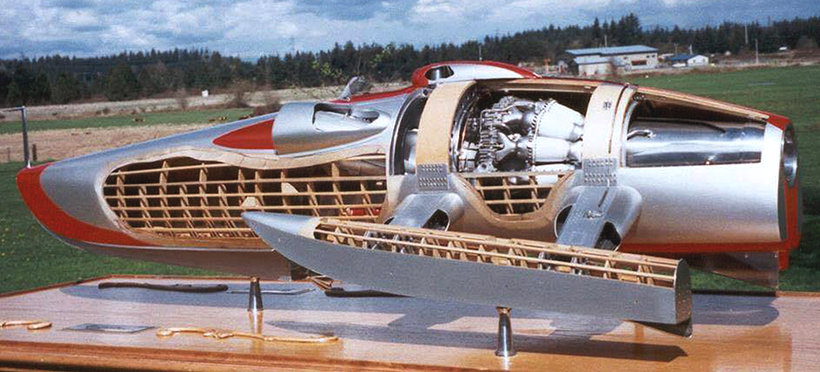

Ron Ayers’ radio-controlled turbine model of Crusader is superb.

Cobb, who had chosen not to wear the craft’s rudimentary safety belt, had been thrown forward out of the cockpit and bounced across the surface of the water, traveling some 150 yards, before finally coming to a halt. When he was pulled from the water he was inanimate; his neck had been broken.

Cobb’s wife, Vicki, had witnessed the crash from the end of Temple Pier, and was led away to the privacy of the project headquarters, a second-hand caravan parked by the boat house. On the water, there was little to be seen, one hatch of three square feet, and a myriad of tiny silver and red shards, all of which was recovered and, at Vicki’s request, burnt.

This cutaway was produced for Motor Boat and Yachting magazine in 1952, with the help of Vosper. It clearly shows the two alloy ring bulkheads, but also claims that the bottom of the hull is metal.

(Pic: Motor Boat and Yachting)

At the time the disaster – the loss of a speed hero and the total destruction of an experimental boat – was accepted by most as just a tragic accident; the inevitability of pushing boundaries beyond what was considered the norm. But, behind the scenes, there was ill feeling and thoughts that perhaps mistakes had been made.

Some made much of the three small waves that had appeared, and the repairs that had be made to the boat on site. But, with the passing of time, all this was forgotten; it was a brave attempt that simply hadn’t worked.

Now, some 70 years later, and having gathered together as much of the original documentation that still survives, another story has emerged, that suggests that Crusader was doomed, although the concept should have worked. A weakness in the hull, compounded by an enforced high centre of gravity, less than perfect conditions and a pilot keen to ‘put on a show’ for his new-found friends, more or less condemned the project to failure, but the seeds had been sown long before the first piece of wood had been cut.

Time-matched stills of the crash from the BBC and Movietone News films show that John Cobb’s head was moving violently back and forth onto the steering wheel, suggesting that he was probably dead before the boat crashed. (Pic: BBC/Movietone News film archives)

Hindsight is a marvellous thing. It’s so much easier to see things with the passing of time, but within months of the accident, Railton was discussing the construction of a new boat, to prove the theory was right. Along with the executor of Cobb’s estate, and George Eyston, Railton got as far as an initial design and a water tank test model.

Simultaneously, Donald Campbell, still trying to successfully emulate his father, was not only asking Railton for advice, but also asking Eyston to persuade Castrol to sponsor him.

Once Railton had met with Campbell’s designers, Ken and Lewis Norris, both he and Eyston decided that was where the future lay, and their plans were shelved, the model put away, and Railton agreed to help the Norris brothers with their analysis of the Crusader crash, to aid in the design of what was to become the incredibly successful Bluebird K7.

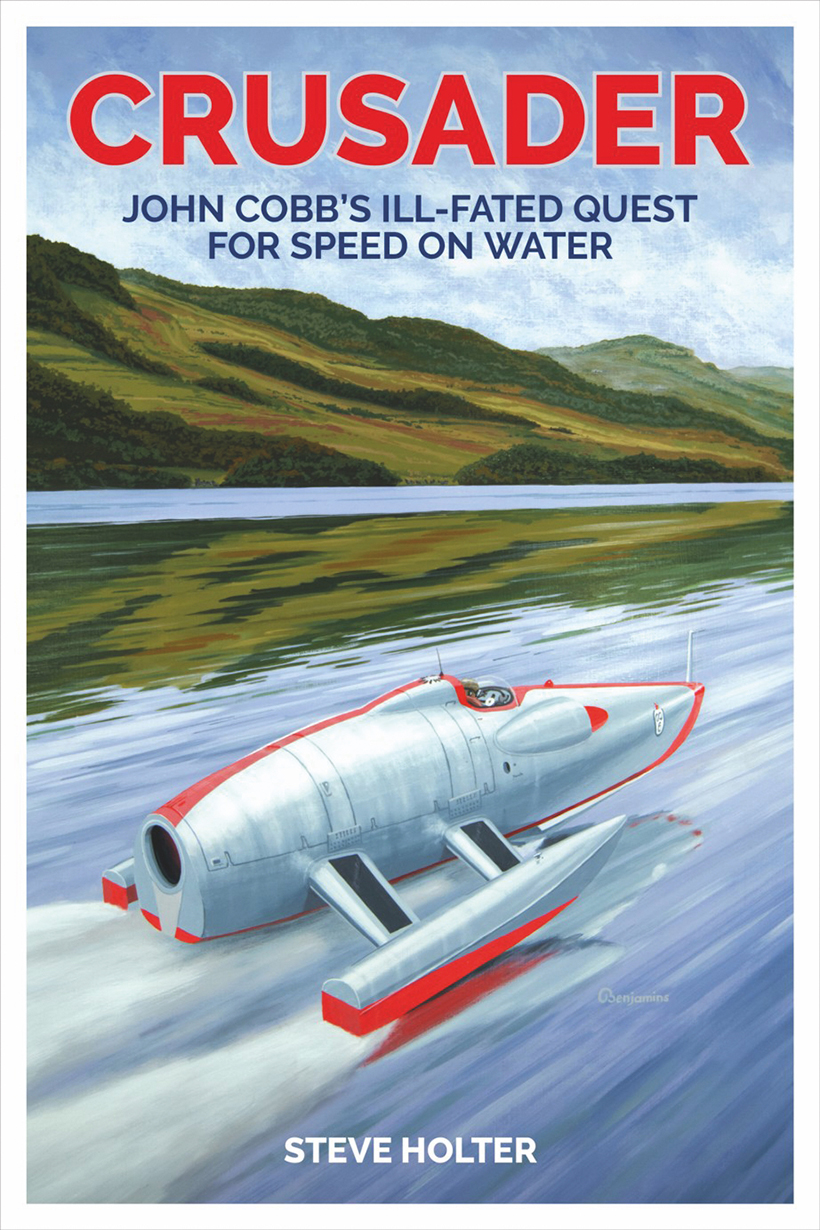

This Arthur Benjamins painting portrays Crusader in September 1952, and it makes a spectacular cover for this superb book that adds so much to what has been written before and long forgotten.

And with that, the saga might have come to an end. Railton retired to California, the model of Crusader II disappeared and, to anyone who saw the newsreel footage of Crusader’s demise, she had simply blown apart.

Things, however, can change quickly. The model was discovered during research for the book, CRUSADER. John Cobb’s ill-fated quest for speed on water, and it so intrigued Richard Noble and designer of Thrust SSC, Ron Ayers, that a radio-controlled, turbine powered model is under test, and quite successfully too.

Crash analysis, using the latest techniques, for the Crusader book, also suggested that the hull had actually failed before it’s final dive into the loch but, of course, there was no way of proving this, until Craig Wallace of Kongsberg Maritime succeeded in the monumental task of finding and filming the remains of Crusader on the bottom of Loch Ness. She lies at the bottom of an enormous underwater cliff, missing one sponson, upside down, and broken in two, leaving a shattered cockpit area, just at the point the third alloy bulkhead should have been.

For a money-saving subscription to Old Glory magazine, simply click here