Famous Royal Navy battleship

Posted by Chris Graham on 24th October 2021

Patrick Boniface reflects on a famous Royal Navy battleship and nuclear-powered submarine both with the famous name, Dreadnought.

No fewer than 13 Royal Navy vessels have born the name Dreadnought since 1553, but it’s this 1906 battleship which lent her name to a whole class of warship.

In a quiet corner of Rosyth Dockyard, in Scotland, lies a small but hugely significant piece of naval history that’s been largely forgotten. Its sleek, black and sinister outline clearly identifies it as a submarine, but other markings, names and its distinctive conning tower have all been removed.

This gently rusting hulk is what remains of Britain’s first nuclear-powered submarine, HMS Dreadnought, which entered service in 1963. She was not, however, the first revolutionary warship to bear the name, nor will she be the last, as a new and huge ballistic missile submarine class bearing the name is currently under construction.

The battleship

Fierce rivalry between the world’s leading naval powers at the turn of the 20th century led to a competition to design and build the best naval warships. This rivalry involved Japan, the United States, France, Germany, Italy and, of course, the world’s then premier naval power, Great Britain.

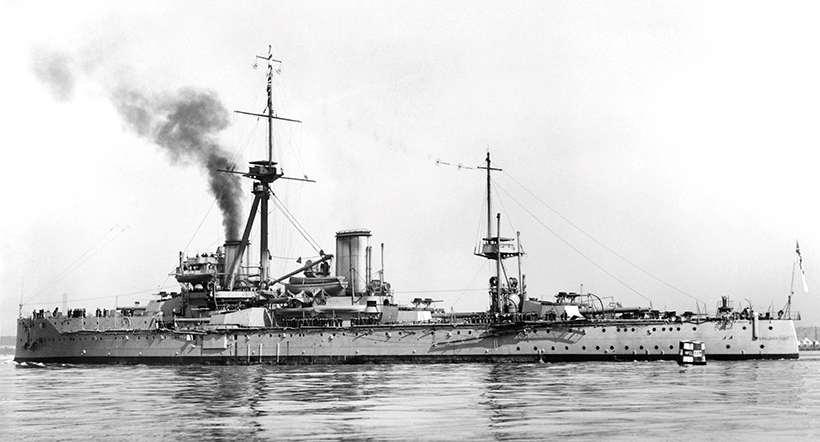

HMS Dreadnought after her keel had been laid in 1906. She was built in great secrecy and at extraordinary speed at Portsmouth Dockyard.

Prior to 1906, battleships were designed primarily to get as many guns afloat as possible and, thus, overpower any aggressor. The guns’ distribution aboard ships involved using different calibres and sizes, and could be cumbersome. These ships became known as the ‘Pre-Dreadnoughts’. They continued to play an important role in naval fleets around the world, but their capabilities were inferior to those of the new Dreadnought.

Dreadnought was the brainchild of Sir John ‘Jacky’ Fisher, First Sea Lord of the Royal Navy. Soon after his appointment to the position, he ordered designs to be drawn up for a new type of battleship, which had only a single calibre main gun, in this case 12 inches, and a speed of 21 knots, greater than most of the existing ships. To achieve the latter, he specified a new type of Parson’s direct-drive turbine be installed, making her the first capital ship to be equipped with these engines.

HMS Dreadnought in all her glory.

Steam was produced by 18 Babcock & Wilcox boilers housed in three boiler rooms. The ship was also to have improved Krupp armour plating, protecting the vital areas, and improved sub-division of compartments to protect against torpedo and bomb attack. As a result, the ship was much larger than the contemporary Lord Nelson class battleships.

Dreadnought had an overall length of 527ft, a beam of 82ft 1in and a draught of 29ft 7.5in. She displaced 18,410 tons and was armed with 10 45-calibre BL 12 Mark X guns arranged in five turrets. Three of the turrets, unlike in most previous classes of battleship, were mounted on the centreline of the ship, allowing the guns to aim at targets on either side of the ship.

Two further 12-inch turrets (P and Q) were mounted as ‘wing turrets’, roughly amidships. Each gun could fire an 850lb shell and had a range of 16,450 yards. HMS Dreadnought’s secondary armament consisted of 27 50-calibre, three-inch 12-pounder Mk.1 guns, a pair of QF six-pounder Hotchkiss AA guns and five underwater torpedo tubes. In 1906 fire control technology was in its infancy, but Dreadnought was fitted with one of the first Barr & Stroud FQ-2 electronic rangefinders.

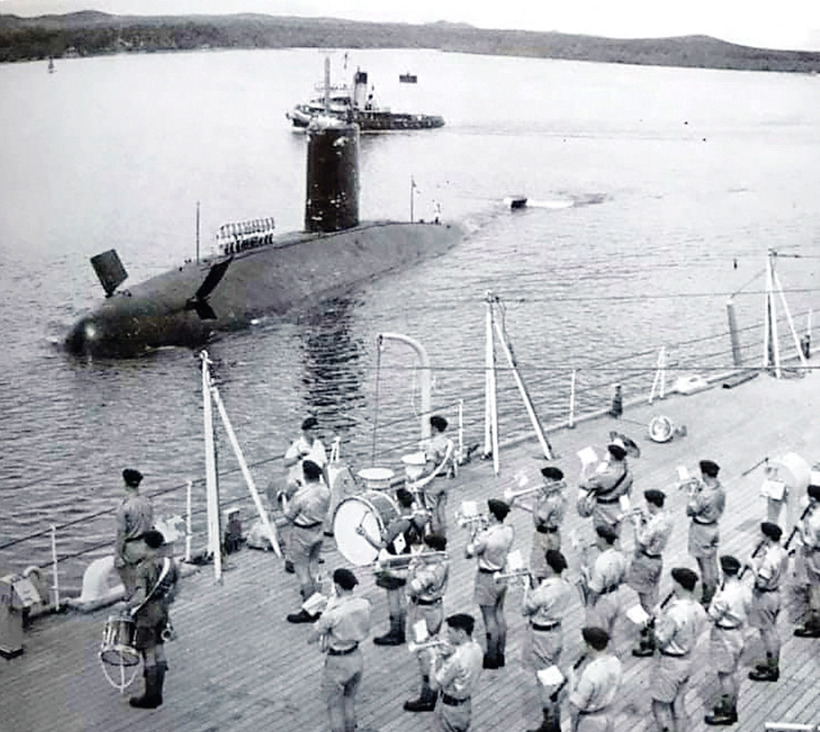

HMS Dreadnought coming alongside HMS Forth, in Singapore, November 1967.

Construction of the new ship started with the stockpiling of a great amount of material, to ensure that the ship’s extremely tight delivery schedule – of one year – was met. On October 2nd, 1905, work started on the ship proper, at Portsmouth Dockyard’s No.5 slip. Great secrecy surrounded the project, and details of the ship’s construction were given as if she was just another ordinary vessel being built by the yard.

Men working on the ship had to put in 69-hour weeks, including compulsory overtime, and only had half-hour lunchbreaks. On February 10th, 1906, with a bottle of Australian wine, the ship was christened HMS Dreadnought by King Edward VII after only four months on the slipway, and just six days after the hull had been completed. The bottle failed to smash across the new battleship’s bows, despite several attempts. The battleship was then moved into No.15 dry dock to be completed. Only when she was handed over to the Royal Navy, on December 11th, 1906, was it announced how revolutionary this new battleship truly was.

During trials off Cornwall, Dreadnought reached 21.6 knots on the measured mile. Further trials took place in the Mediterranean. HMS Dreadnought caught the attention of the world’s media, while even her designers were taken aback by the success of the new design. Captain Reginald Bacon, Fisher’s former Naval Assistant Designs said: “No member of the Committee on Designs dared to hope that all the innovations introduced would have turned out as successfully as had been the case.”

HMS Dreadnought alongside at Singapore, in 1967. (Pic: Author’s collection)

The construction of this super warship led to an increase in the rivalry between the great naval powers, as each tried to outdo the other with ever more powerful vessels. At the start of World War I, Dreadnought was based at Scapa Flow but, despite being such a technological marvel at the time of her completion, she played only a small part in the war. Her only notable contribution was the ramming and sinking of the German submarine U-29, which happened on March 18th, 1915. After the war, she was relegated to secondary roles, before being sold on March 31st, 1920, to Thos W Ward at Inverkeithing, for scrap.

Nuclear submarine

The next Dreadnought was built in the post-World War II era. The development of atomic power from the 1940s led to the building of nuclear-powered warships, which were found to be particularly well suited for underwater warfare. Since 1946, the Royal Navy had been investigating this form of propulsion, but it was the United States, in 1955, that built the first atomic submarine, USS Nautilus. She transformed submarine warfare, as no longer did submarines have to surface to recharge batteries using diesel engines and, thus, give away their position.

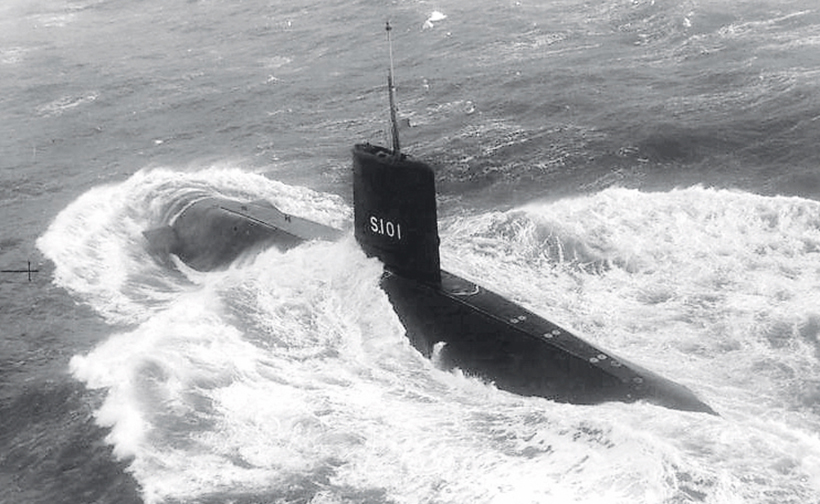

The nuclear-powered submarine HMS Dreadnought at sea. She was the first British submarine to surface at the North Pole.

Nuclear power also meant the submarine had a virtually unlimited range and endurance. In fact, the submarine was limited only by the endurance of her crew and the amount of supplies that could be carried on board. Seeing the capabilities of USS Nautilus, the Royal Navy realised that this was the future. However, America wasn’t, initially, agreeable to sharing the technology, not even with a partner nation like Great Britain.

It was only through gentle persuasion and negotiation from the likes of Admiral The Earl Mountbatten of Burma, the First Sea Lord, and Flag Officer Submarines Sir Wilfred Woods, and on the American side by US Navy Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Arleigh Burke, that the USA eventually shared some of its technology. Britain had its own nuclear programme under way but, to meet tight in-service dates, the design of the new submarine involved some compromises; namely that it would have an American S5W reactor, although everything else was of British construction.

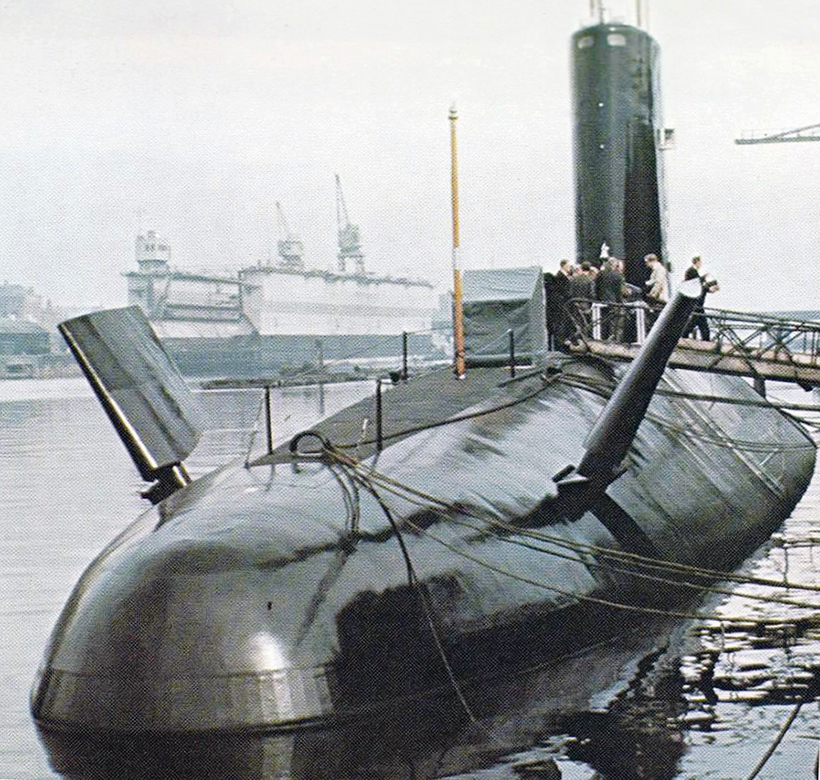

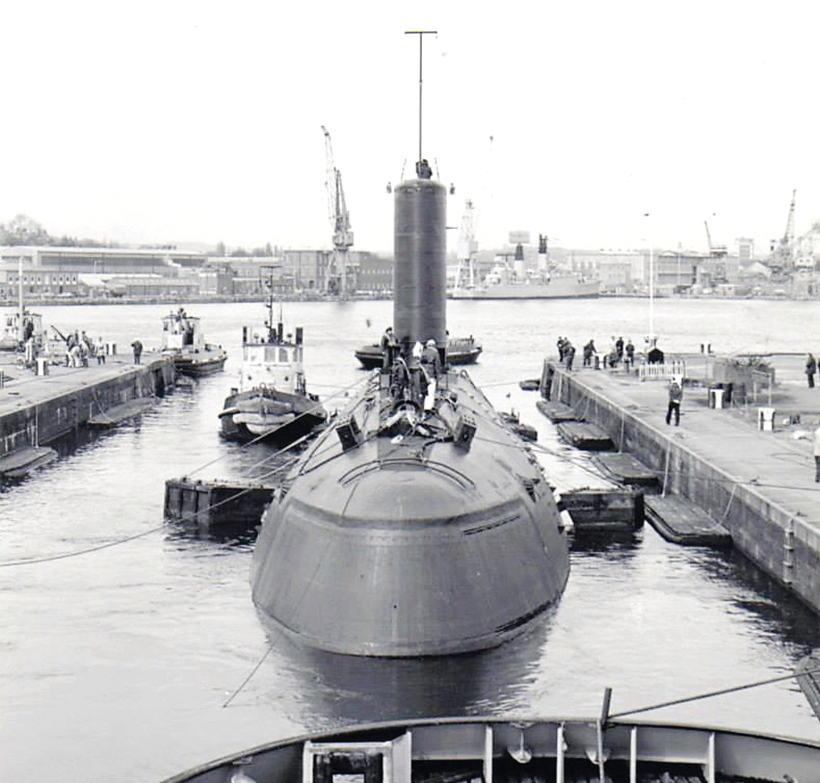

HMS Dreadnought at Chatham Dockyard, being eased into the River Medway.

On June 12th, 1959, the first steel plates of the new submarine were laid down at Vickers Shipbuilding at Barrow-in-Furness. Launched by Queen Elizabeth II on October 21st, 1960, (Trafalgar Day), she was commissioned into the Royal Navy on April 17th, 1963. Just like her predecessor 50 years before, the new submarine – HMS Dreadnought – revolutionised underwater warfare, overnight.

Submarine operations are notoriously secretive, but on June 24th, 1967, it’s known that the submarine was ordered to sink the wreck of the German ship Essberger Chemist with three torpedoes and, in 1977, she was part of a Royal Navy task force sent to the South Atlantic to deter Argentine invasion plans for the Falkland Islands, together with the frigates HMS Alacrity and HMS Phoebe, during Operation Journeyman.

By the late 1970s, Dreadnought’s maintenance was becoming an issue, and she was withdrawn from the fleet in 1980. She spent some time in reserve at Chatham Dockyard before that dockyard closed, and she was then moved to Rosyth Dockyard in Scotland, where she’s been ever since. She and other retired nuclear boats are stored awaiting their fate, as the Ministry of Defence’s Submarine Dismantling Project (SDP) is developed.

Her final resting place; HMS Dreadnought laid up at Rosyth. (Pic: David C Matthews)

There is a campaign to preserve the submarine, possibly at Barrow-in-Furness, but such ambitions are fraught with difficulties, not least because of the issues of making the nuclear reactor in the submarine safe.

A 21st century Dreadnought

The future HMS Dreadnought will be bigger and more capable than her predecessor, and will carry the UK’s independent nuclear deterrent into the second-half of the 21st century, replacing the current Vanguard class boats. Like the Vanguards, the new Dreadnought class, which will consist of HMS Dreadnought, HMS Valiant, HMS Warspite and HMS King George VI, will be armed with 16 Trident II-D-5 missiles, each armed with up to eight independent delivery systems.

An impression of the future HMS Dreadnought.

In 2016, the government announced its intention to build a successor class of ballistic missile submarines, and that the first in the four-vessel programme would be named HMS Dreadnought. The design process, however, had begun in May 2011, when the first initial assessment phase for the new submarines’ design commenced. It also saw the ordering of the first long-lead items, such as the specialist steel needed for the hull, and some nuclear components.

The first steel was cut for the future HMS Dreadnought on October 6th, 2016. The four-vessel programme will cost the British taxpayers £31 billion, and HMS Dreadnought is expected to enter service around 2028. The vessels are expected to have a service life of between 35 and 40 years.

The future HMS Dreadnought.

The first three craft are named in honour of famous battleships of the 20th century, although Warspite and Valiant were also used for two of the RN’s first-generation SSNs. The fourth of the ballistic missile submarines, HMS King George VI, will become the first Royal Navy vessel to be named in honour of father of the Queen, who was also a former naval officer.

Displacement: 17,200 tons

(16,900 long tons; 19,000 short tons)

Dimensions: 153.6m (504ft) x 12.8m (42ft) x 12m (39ft 4in)

Propulsion: Rolls-Royce PWR3 nuclear reactor, turbo-electric drive, pump-jet. Range limited only by food and mechanical components

Complement: 130

Armament: Four 21-inch (533mm) torpedo tubes for: Spearfish heavyweight torpedoes; 12 ballistic missile tubes for 8-12 Lockheed Trident II D5 SLBMs (carrying up to eight warheads each)

For a money-saving subscription to Ships Monthly magazine, simply click here

Previous Post

Scenic Railways 4 just published!

Next Post

The Australian domestic power supply industry’s interesting trucks