Fine engineering details on stationary engines

Posted by Chris Graham on 12th July 2024

Sam Bloake picks out the fine engineering details on stationary engines that most interest and impress him.

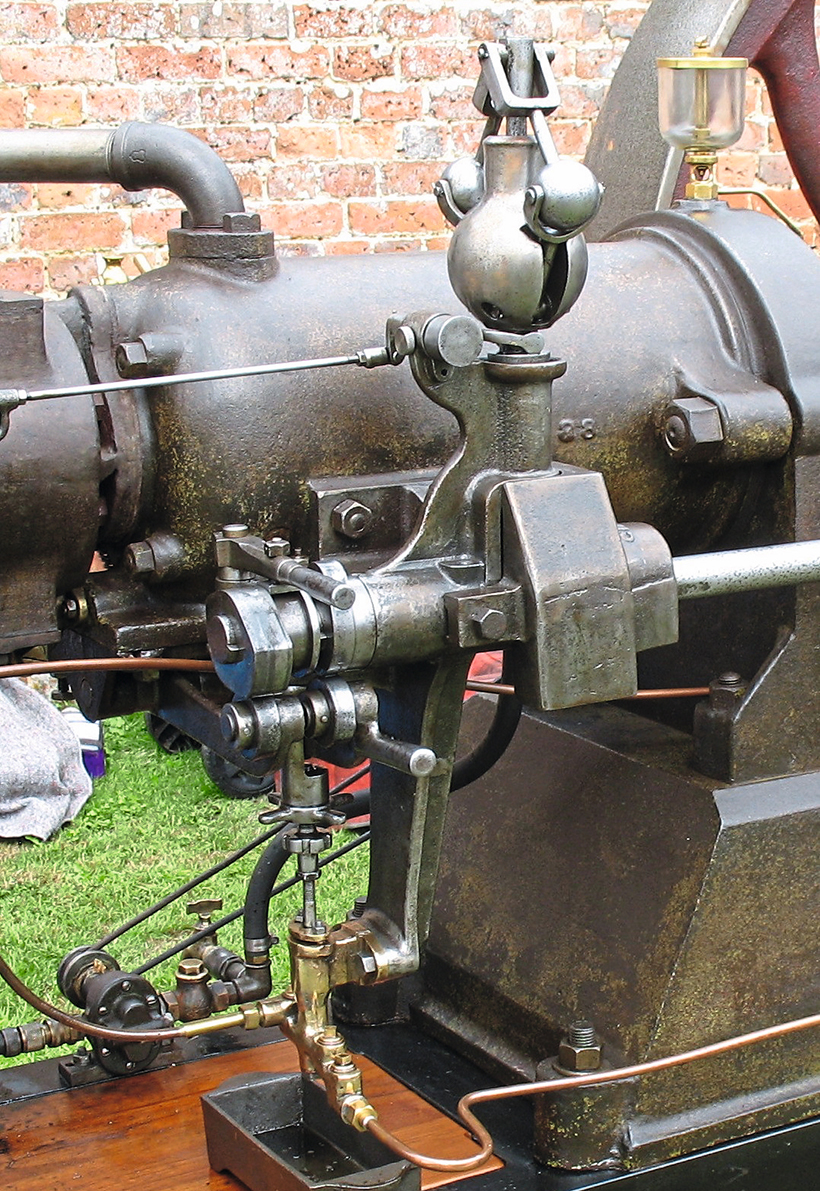

This style of cylinder oiler was installed on many early engines; this example, with its bell-shaped cover in place was installed on a Crossley Brothers engine…

Am I alone in being fascinated by some of the little features that can be found on stationary engines? I think we’re all in agreement that it’s a pleasure to look at an old engine. I don’t fully know exactly what it is that catches our attention, maybe it’s the age of it, or that it has a history of hard work. Maybe it’s the lines of the overall shape, the simplicity or complexity of the design. It could be almost anything, and no doubt it’s different for different people.

… and here with the cover removed.(Photo: Patrick Knight.)

When I’m in front of an engine I quite often find myself looking at a single part of it, admiring how it works or maybe its elegance. Possibly my favourite feature, only found on earlier engines, is the belt-driven cylinder oiler. They are so simple and ingenious in the way the small crank inside them dips a piece of wire or a wick into the oil reservoir and then wipes it against a pin to deposit a small amount of oil that runs into a tube that carries it along to the cylinder where it lubricates the piston. It’s fascinating.

The flat flywheel face. (Photo: Philip Thornton-Evison)

Various manufacturers like Crossley and Campbell made them to their own design, but they all work the same way. I’m obviously not alone in admiring the design as, most of the time, you’ll see that the protective cover has been removed when the engine is running so that the inner workings can be seen.

Crowning on the face of a flywheel can vastly change its appearance. It’s odd to think that a slight radius can have such an impact. Many early Lister engines had crowned flywheels, and in my opinion look lovely. (Photo: Philip Thorton-Evison)

One of the simplest features that go unseen by many is a crowned flywheel. This is where the face of the wheel is turned to a slight radius rather than just being flat. The reason for doing this is help keep a flat belt running centrally on it when driving something (there’s some science involved here in that the belt has fractionally increased tension at the centre of the crowning and this, combined with a similarly fractional increase of surface speed, encourages the belt to run towards the middle, helping to prevent it from running off altogether). The radius used isn’t very large, yet the difference it can make to the look of a flywheel is huge.

Sometimes it’s not the little things that catches the eye (and sometimes the imagination) – with flywheels, bigger is definitely better! (Photo: Ian Skuse)

Flywheels can be things of beauty in themselves. Different manufacturers had their own styles, and often the make of engine is instantly recognisable just by the flywheel. For example, Ruston’s flywheels tended to use a heavy hub with slimmer rims while Crossley preferred a heavier rim, Blackstone’s spokes have those odd bosses cast into them (was it ever ascertained what they were for?). The big difference you’ll immediately see is the straight spoke and curved spoke, and there has been loads of discussion over the years as to which design is mechanically superior.

When it comes to looks, Hornsby fly-ball governors are hard to beat.

It’s claimed that curved spokes were easier to cast as there was less likelihood of them cracking due to shrinkage during cooling, yet straight spokes are way more common. Then there’s an argument about whether the curve should run in the direction of rotation or against it. I don’t think there has ever been a definitive answer, but I’ll go out on a limb here and say an elegant curved spoke always looks nicer than a plain, straight one. However, let’s not discount the solid flywheels as sometimes they can be very aesthetic.

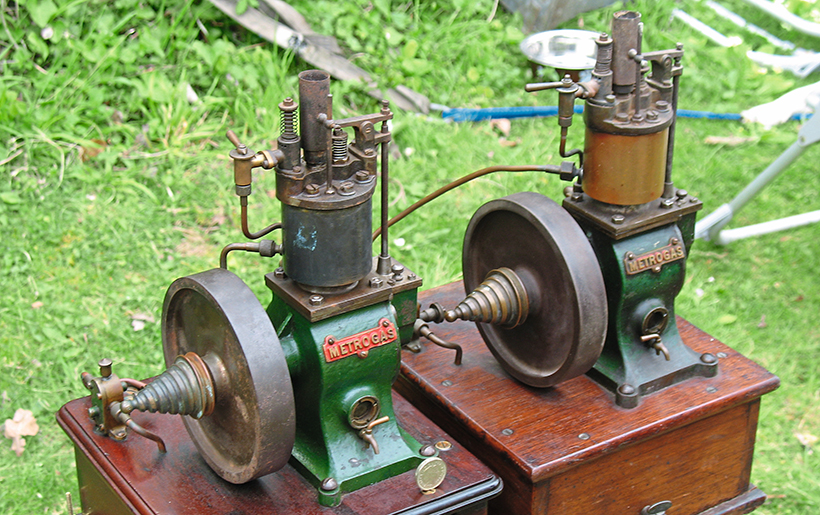

Solid flywheels can still look nice; in particular those fitted on Metro gas engines with their curious scrolled taper. (Photo: Tim Keenan)

Exposed governors always catch the eye. To coin the old expression, ‘You can’t beat a good set of balls!’ Much the same as flywheels, a manufacturer can often be determined just from the shape of the governor. The pre-1912 Hornsby styles are a fabulous, iconic shape. They’re not all spinny-roundy types though. One of the most fascinating styles to watch in operation is the pendulum or inertia design. Again, most of the bigger manufacturers dabbled with this.

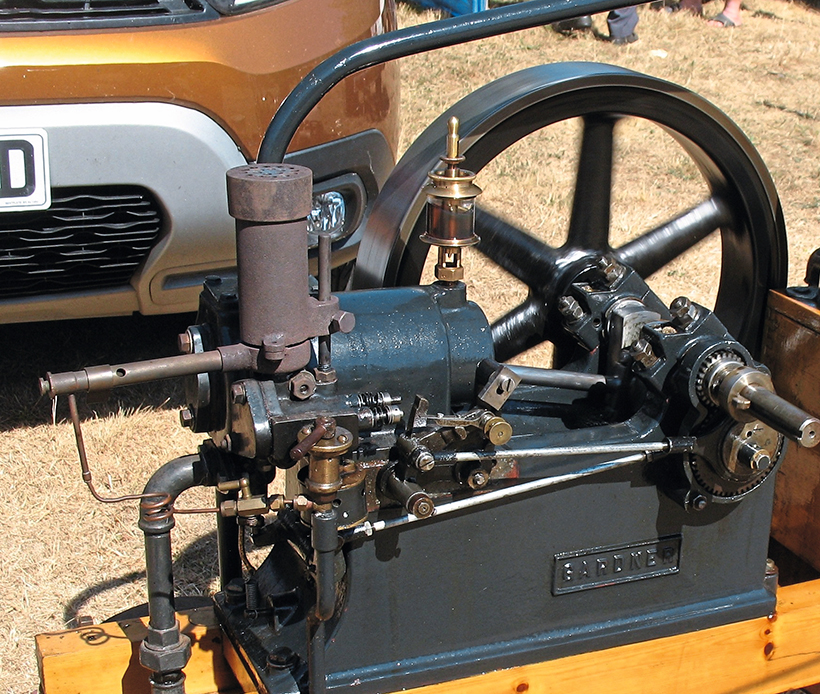

The inertia governor used on this Gardner hot-tube engine is a thing of wonder; watching it engage and disengage to control engine speed can be quite hypnotic. (Photo: Patrick Knight)

The idea of a pivoted weight forming part of the valve linkage that will disengage if the operating cam hits it too quickly is wonderfully simple. Gardner engines have very complicated-looking valve gear with their eccentrics and long rods, and watching it all moving and the little pendulum rocking in and out of engagement is quite mesmerising.

Hardy Padmore used a chain-driven camshaft that to the casual onlooker appears to be something cobbled together from odd parts that were kicking around a bike repair shop.

There are a multitude of interesting little design features to be found on old engines – Bulldogs rely on the exhaust valve arm being pulled rather than pushed like most other engines, for a while the Victoria used a curious ‘beaked’ design of mechanism to trip the flick magneto, Stickney have the most bizarre camshaft and fuelling arrangements, Hardy Padmore used a chain-driven camshaft that, to the casual onlooker, appears to be something cobbled together from odd parts that were kicking around a bike repair shop, and Bentalls have a clever little mechanism to arrest and then release the magneto drive to give an impulse of current to help starting. The list goes on. So next time you see an engine, maybe have a closer look at the little things. They can be quite fascinating.

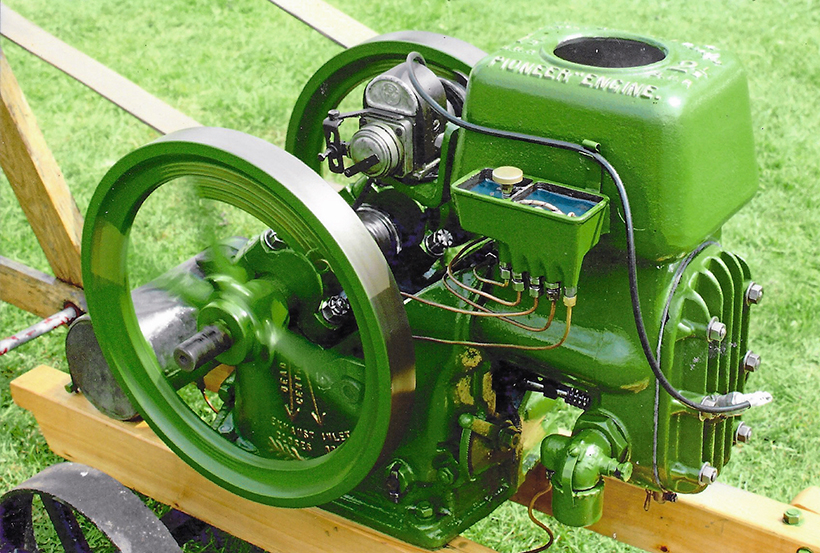

EH Bentall employed this rather unusual oiling system on its horizontal ‘Pioneer’ engines. (Photo: Alan Cullen)

Often hard to see, and no doubt something missed by the public when watching an engine, the drip of oil that keeps things lubricated (Photo: Philip Thornton-Evison)

This feature comes from the latest issue of Stationary Engine, and you can get a money-saving subscription to this magazine simply by clicking HERE

Previous Post

Classic trucks at the Fenland Classic Vehicle Show

Next Post

Beautifully restored 1980s Massey Ferguson 698