The dramatic wartime bombing of HMS Sussex

Posted by Chris Graham on 20th December 2022

Bob Wright, chairman of the Scottish Fire Heritage Group, recounts the dramatic bombing of the cruiser HMS Sussex, in 1940.

The County class heavy cruiser HMS Sussex at Portsmouth in April 1929, shortly after she had been commissioned. (Supplied by Campbell McCutcheon)

To many older Glaswegians, especially those who lived through World War II in the Partick and Yorkhill areas, the bombing of the cruiser HMS Sussex in 1940 will long be remembered as the ship ‘with the bomb that went doon the funnel’. HMS Sussex was a London class cruiser of 10,000 tons and, during August 1940, she was in the Clyde to have a turbine re-bladed, with the Fairfield Shipbuilding and Engineering and Alexander Stephen & Co of Linthouse contracted for the work. The repair was expected to last six weeks, but was completed four days ahead of schedule and the crew had been instructed to rejoin their ship by midnight on 17th September, 1940.

Sussex was made ready for sea, being fully stored and armed. She lay berthed in the West Basin of Yorkhill Quay, with only final engine room adjustments to be made and 300-400 naval personnel on board. Her intended sailing date was 23rd September, 1940, and she was to go to Murmansk on convoy duty. But, sadly, Sussex never took part in those operations.

In her original configuration, HMS Sussex carried a range of armament, including eight 8-inch dual guns, four 4-inch single AA guns and four 2-pdr single pom-poms. (Supplied by Campbell McCutcheon)

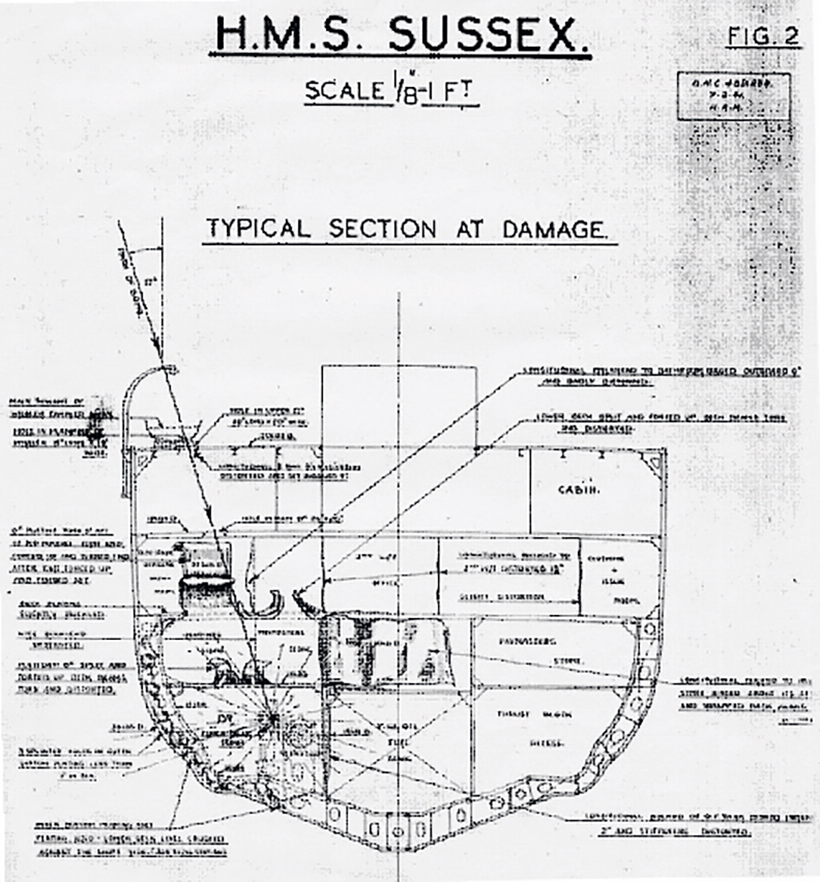

At 0240 on Wednesday, 18th September a lone German bomber appeared over Yorkhill and scored a direct hit on the ship with one 250kg armour-piercing delayed-action fused bomb. The trajectory of the bomb was such that it passed clean through the ship’s starboard whaler (boat), pierced the upper deck abreast of the mainmast close to ‘X’ gun turret, and then penetrated another three decks before exploding in the starboard thrust block compartment, causing severe structural and splinter damage. What’s more, fuel oil from the ruptured storage tanks caused a serious fire in the aft engine room.

The Royal Navy onboard crew immediately started to fight the fire, but this proved unsuccessful as the fire pumps and bilge pumps had been put out of action by the explosion. The Glasgow Fire Brigade were called and, at 0330, appliances were dispatched from both Partick and the West fire stations, with trailer pumps coming from nearby Auxiliary Fire Stations.

Martin Chadwick, who had only been appointed Firemaster of Glasgow Fire Brigade 15 weeks previously, was inspecting bomb damage in Partick at the time and, upon hearing the request for assistance, proceeded to the incident. On arrival at Yorkhill Quay, he was informed that most of the Royal Navy personnel had been taken off the ship, although several wounded sailors were still being carried from the cruiser.

HMS Sussex at Portsmouth in her prime. (Supplied by Campbell McCutcheon)

Smoke and flames were issuing from the superstructure towards the rear of the ship. With a rapidly deteriorating fire situation and the possibility of a magazine explosion, the decision was taken to flood the magazine. Attempts were made to gain access to the engine room and the seat of the fire but, due to the complexity of the warship’s design, this proved unsuccessful. In addition to the intense heat and thick black smoke, the effects of the explosion had also disabled the ship’s electrical system, and the fire brigade crews had to work in complete darkness.

Firemaster Chadwick mentioned in his report that men working in breathing apparatus were unable to penetrate any great distance due to the unfamiliarity and the compartmentalisation of the ship. The fire had to be tackled from above and this decision ruled out the use of foam, as it could not be projected directly onto the burning oil.

Measures were implemented to cool the steelwork surrounding the magazines in which the cordite charges and other ammunition were stored. The Royal Navy Commander on HMS Sussex informed Chadwick that this action was vitally important, as any overheating of the contents of the magazine could result in a catastrophic explosion.

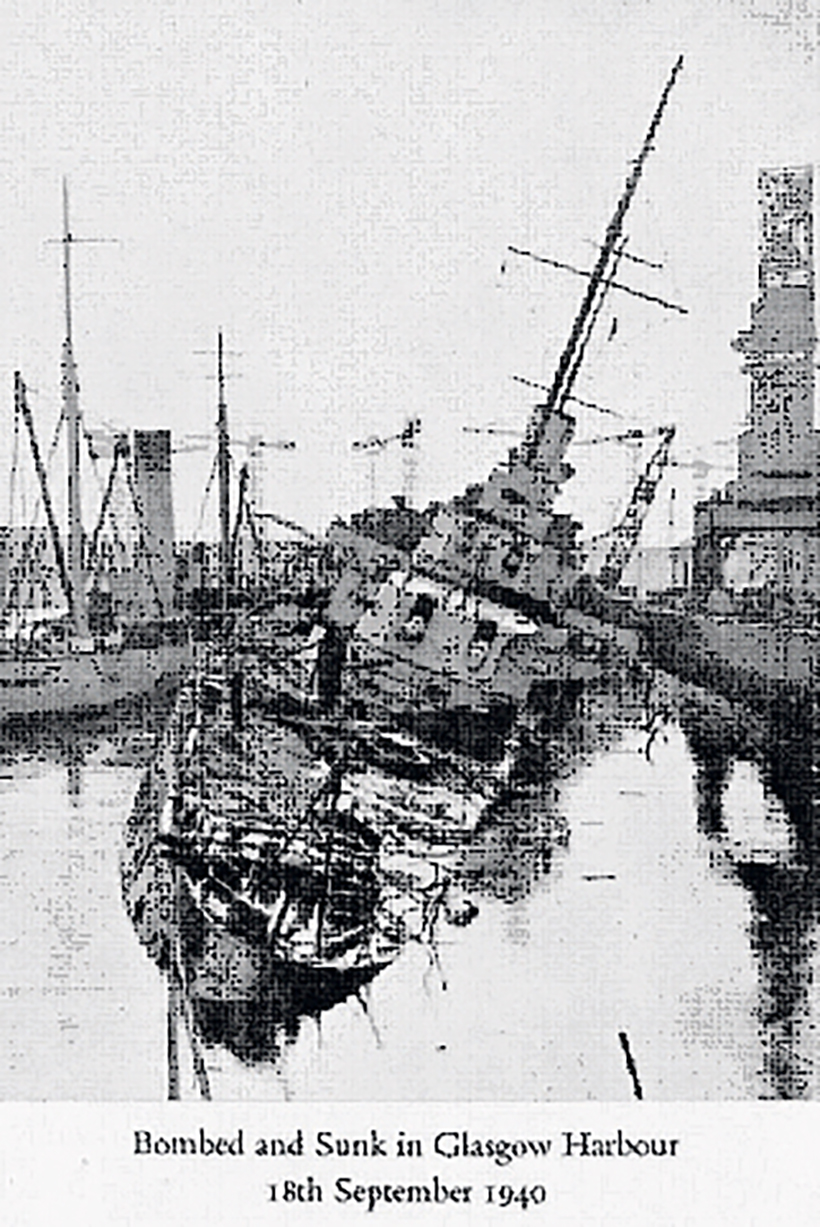

HMS Sussex submerged and partially sunk in Glasgow harbour on 18th September, 1940…

The surrounding areas of Yorkhill and Partick, and the nearby Royal Hospital for Sick Children, were under threat and an evacuation of the immediate vicinity was implemented. One account mentions a human chain of people winding their way through the streets in total darkness to the relative safety of one of the city parks.

Two hours after the first fire brigade crews arrived, the ship began to list to starboard due to the combination of flooding of the magazine spaces and the free flow of oil from the various damaged tanks and ruptured oil pipes. The hull had also been perforated by splinters from the initial blast, allowing water to enter the ship. It then became difficult for the fire brigade crews to maintain a footing, and firefighting operations were suspended on the port side of the ship.

… Torpedoes were later recovered from the River Clyde that had broken free from the partially submerged ship.

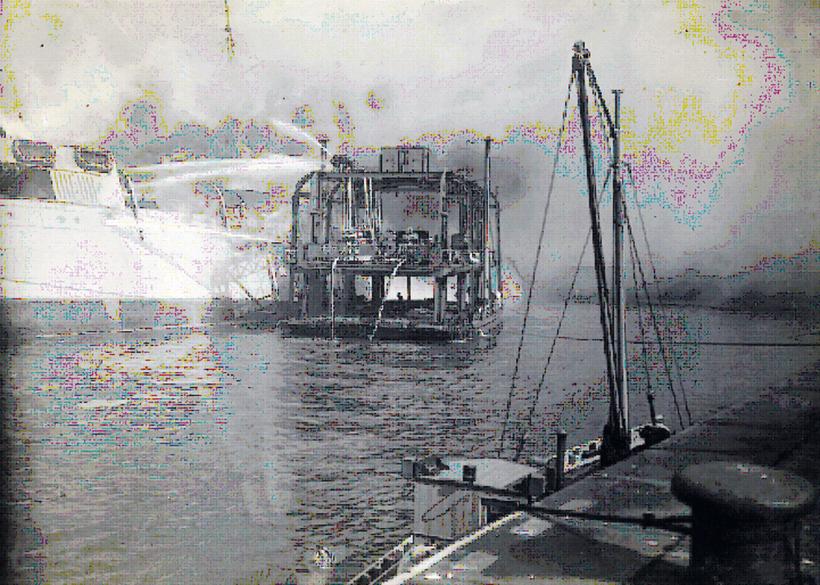

Firemaster Chadwick commandeered the Clyde Navigation Trust’s large vehicular ferry No.4 and three Heavy Mobile Pumps were placed on board and the ferry taken alongside the stricken warship. Although the ferry was ideal for cross river navigation, it was not particularly good at manoeuvring, and great difficulty was encountered in trying to get the vessel into the required position.

However, the crews of the appliances got their pumps ready and lowered them over the stern ready to commence pumping operations. The ferry had a moveable vehicle platform and a high gantry running fore and aft onto which the jets were placed and directed towards the burning ship. The Branchmen had explicit instructions to direct their cooling jets onto the torpedoes stored in tubes on the upper deck and also onto decks under which explosives were known to be housed.

After 10 hours of hard and exhausting work, Chadwick and his fire crews were able to gain access to the lower decks of the cruiser. Severe fire could still be seen through gland holes in a bulkhead and, rather than risk a vapour explosion by opening up any of the bulkhead doors, jets were directed through the gland holes to effect further cooling.

Diagram showing the trajectory of the 250kg armour-piercing bomb and the damage inflicted.

Progress was slow and great difficulty was encountered by those trying to work with high-powered jets on a ship that was listing now at almost 23 degrees. When the entrances were cooled sufficiently, the bulkhead doors were opened and personnel were then able to get directly to the seat of the fire. At 0400 on Thursday, 19th September, the last of the fires on board HMS Sussex were finally extinguished.

Re-floated and repaired

Although badly damaged, Sussex was re-floated, towed into dry dock and subsequently repaired by Alexander Stephen & Co at Govan. The repairs took 21 months and involved rebuilding the entire aft section of the ship. She was also fitted with new radar equipment, fire control equipment, 10 Oerlikon 20mm cannon and two eight-barrelled Pom Pom guns.

The Clyde Navigation Trust’s Vehicular Ferry No.4 being used as a firefighting platform on which three heavy pumping units were used to direct water onto the ship in an effort to cool the magazine spaces.

HMS Sussex was recommissioned on 6th August, 1942, and joined the First Cruiser Squadron at Scapa Flow on 4th September that year. Towards the end of the war she saw service in the Pacific and was even hit during a Kamikaze attack. She was one of the first ships to enter Singapore after the cessation of hostilities, and the Japanese surrender was signed on board the cruiser.

HMS Sussex returned to the River Clyde in 1950. It was not a heroic return or for a dry-docking, but rather a one-way trip to the breakers’ yard. She was paid off in 1949, handed over to the British Iron & Steel Corp on 3rd January 1950, and arrived at Dalmuir on 23rd February, where she was broken up by WH Arnott, Young and Company Ltd.

This feature comes from Ships Monthly, and you can get a money-saving subscription to this magazine simply by clicking HERE

Previous Post

Steaming at Platinum Jubilee street party!

Next Post

Dennis built cars as well as trucks!