The tragic, 1956 sinking of Italian liner Andrea Doria

Posted by Chris Graham on 12th January 2023

Dene Bebbington tells the story of the tragic, July 1956 sinking of the Italian liner Andrea Doria, after a collision in fog.

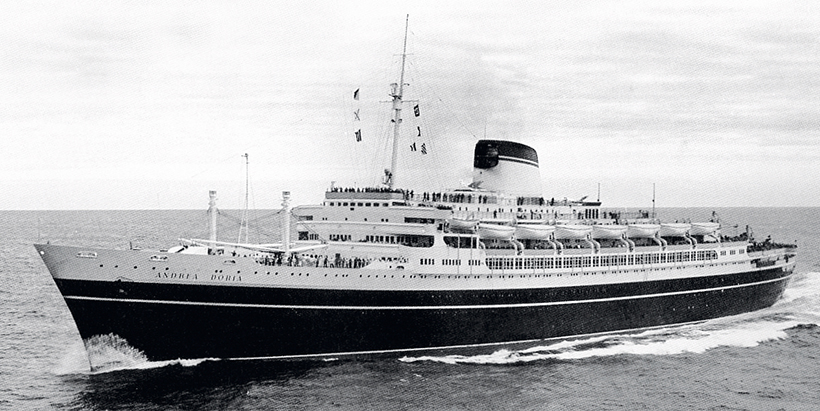

Italian Line’s impressive liner Andrea Doria, photographed in 1955, a year before her sinking. (Pic: Bill Smith, Creative Commons CC BY 2.0)

Shipping lines on both sides of the conflict lost ships during World War II, with many sunk by enemy action or seized as war prizes. Consequently, the post-war era saw companies rebuilding their fleets. The Italian Line was no exception, also taking the opportunity to introduce modern vessels.

Since Italy was one of the Axis powers, Italian Line ships such as the 1932-built Rex and Conte di Savoia, which were mostly laid up from 1940, became wartime targets. Both these ships were eventually sunk by the Allies, although Conte di Savoia was salvaged and rebuilt. In contrast to the pre-war ships, the line’s new post-war ships began with Giulio Cesare, which was launched in May 1950, followed by Augustus in November 1950. A few years later, national pride saw its largest liners, Andrea Doria (29,083gt) and sister ship Cristoforo Colombo (29,191gt), being completed.

A postcard of Andrea Doria in her prime. She was the first ship to feature three outdoor swimming pools, one for each class.

The former had 11 watertight compartments and was built using the two-compartment standard, and consequently Andrea Doria was claimed to be unsinkable. Only a few decades earlier the ill-fated Titanic had been given that epithet, and this should been a warning against similar overconfidence.

Theoretically the double-hulled Andrea Doria could survive if two adjacent compartments were flooded, but there had to be a trade-off in the design for the commercial needs of a liner. A greater number of smaller compartments would have been safer in the event of her being holed, but the downside of such an arrangement was that movement of passengers through the ship would not be as easy. Other safety features included the installation of non-flammable materials, a sprinkler system and fire retardant insulation between the hull and cabin panelling.

Andrea Doria at sea with her portside lifeboats visible. When fully booked, she could accommodate 1,241 passengers in three different classes. (Pic: Public domain)

Since Andrea Doria was to sail an Atlantic route between Genoa and New York, speed was another consideration. The steam turbines turning twin screws could generate 35,000hp, giving a top speed of 26 knots and a service speed of 23 knots. A maximum of 1,241 passengers and 572 crew could be carried and, typical of the era, accommodation was divided into First, Cabin and Tourist classes. The lowest-priced tickets for Tourist class suited migrants, and others of limited means. In return for economy, they were unwittingly, if a serious collision occurred, the most vulnerable in the lower B and C decks.

Built in Genoa

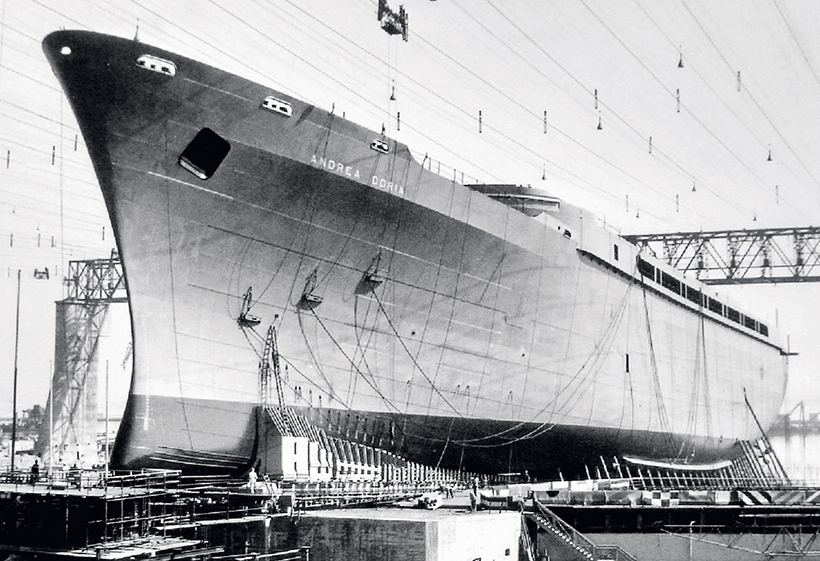

Andrea Doria was laid down at the Ansaldo Shipyard in Genoa in February 1950, with construction taking over a year. She was launched in June 1951 and began her maiden voyage on 14 January 1953. During the first sailing a listing problem was discerned when she was not far from her destination on the United States’ east coast. During a storm the ship was hit broadside by a huge wave, causing her to list 28 degrees, and knocking several passengers to the deck.

Andrea Doria on the slipway at yard No.918 at Ansaldo Shipyard in Genoa, under construction in June 1951. (Pic: Public domain)

Andrea Doria had sufficient lifeboat capacity for all on board: 16 metal boats, eight on each side, could carry up to 2,000 people. In hindsight, the ship’s tendency to list, especially when the fuel tanks were almost empty, was potentially disastrous, regardless of how many lifeboats she carried.

Though the Italian liner could not compete with the size and speed of other ships on the North Atlantic route, such as Queen Elizabeth and United States, she gained a fine reputation for being plushly fitted out, as well as being known as a floating art gallery. Passengers could admire paintings, sculptures and other works of art, while she boasted three outside swimming pools. If nothing else, she was a pretty ship, while also being equipped with radar.

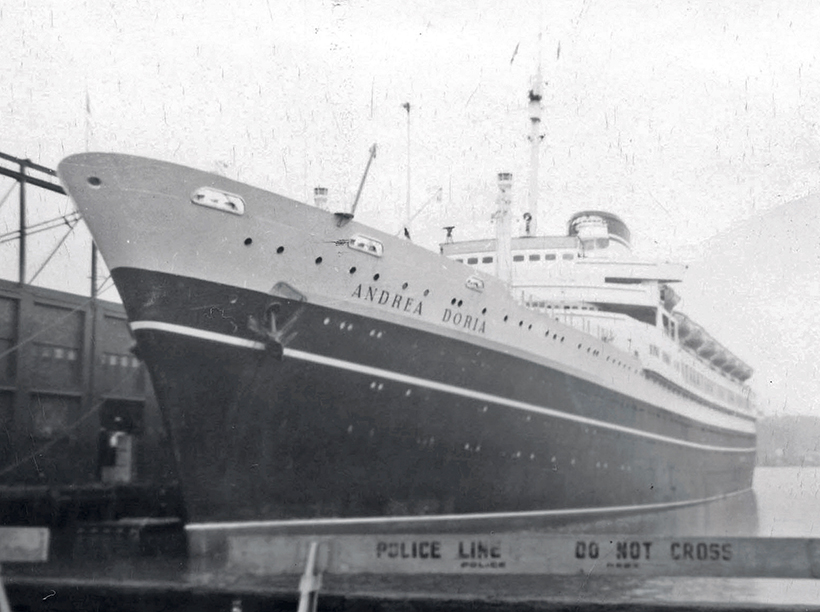

The sleek Andrea Doria moored at dock; she entered service in January 1953, but had a short career of just over three years.

Captained by Piero Calamai, who had nearly 40 years’ seagoing experience, including naval service for which he was twice awarded the Silver Medal of Military Valour, the liner should have been in safe hands. For three years it was.

The danger of fog

Fog in busy shipping lanes is a perennial a danger for mariners. In 1914, two years after Titanic went down, Empress of Ireland sank near the mouth of the St Lawrence river in Canada after a collision in fog. Confusion and mistakes led to over 1,000 lives being lost. Even with the advantage of radar on Andrea Doria, human error could and would play a part. Ironically, on Calamai’s last Andrea Doria voyage before he took command of Cristoforo Colombo, tragedy hit.

Cristoforo Colombo was slightly larger, at 29,191gt, than her sistership. (Pic: Wolfgang Fricke, Creative Commons CC BY 3.0)

Ship captains tread a fine line between ensuring the safety of those on board and keeping as close as possible to a schedule. When fog was encountered south of Nantucket Island on the evening of 25 July 1956, the captain ordered reduced speed, but this only slowed Andrea Doria from 23 to 21.8 knots. The watertight doors were closed as a precaution and the fog-whistle sounded every 100 seconds. On a heading of 267 degrees, the ship’s course was towards the Nantucket lightship in a busy area, nicknamed the ‘Times Square of the Atlantic’.

Meanwhile, Swedish American Line’s 1948-built Stockholm (12,165gt) was departing America and heading to Europe at her top speed of 18 knots, sailing further north than the 1953 North Atlantic Track Agreement allowed for eastbound traffic.

The damaged liner Stockholm limps into port after her collision with Andrea Doria. (Pic: State Library of Queensland/public domain)

After making course corrections, Stockholm’s Third Officer, Johan-Ernst Carstens-Johannsen, who was on duty, spotted the radar blip of a ship coming towards them a couple of degrees off the port bow at an estimated distance of 12 miles. At a combined speed of 39.8 knots this gave about 16 minutes until the ships would pass each other by less than a mile, as estimated by Carstens.

Initially the running lights of Andrea Doria were not visible to the crew of Stockholm who, given the other ship’s speed, did not suspect her to be in fog. When the larger liner was finally spotted, Stockholm steered to starboard to give more clearance for what they thought would be a port-to-port passing. However, there had been a misjudgment of the oncoming ship’s position.

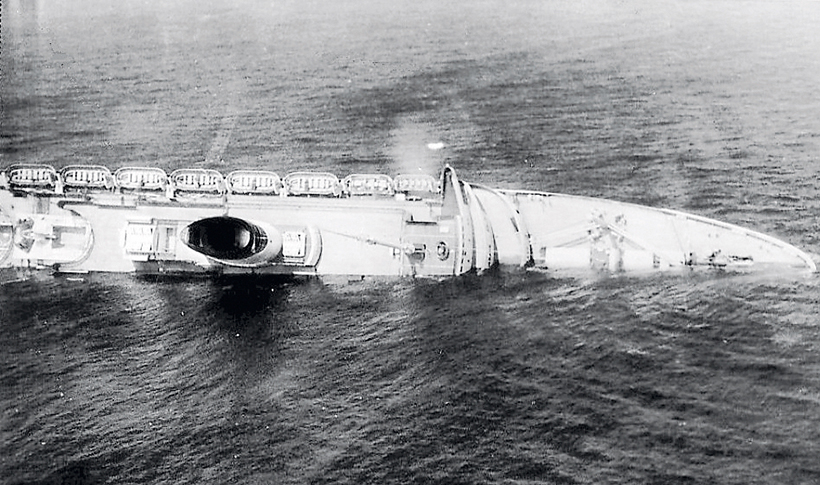

Andrea Doria listing to starboard just before she sank. She was booked to about 90% of her total passenger capacity, with 1,134 passengers aboard: 190 in first class, 267 in cabin class and 677 in tourist class; with a crew of 572; a total of 1,706 persons were on board.

When Stockholm was finally spotted by Andrea Doria’s crew, Captain Calamai ordered the ship be steered hard to port, rather than steering so that there would be a glancing blow. This decision made tragedy inevitable.

Andrew Doria was hit amidships just after 23:00, the Swedish liner’s ice-breaking prow slicing into the Italian ship. Despite efforts to reduce the starboard list by pumping water to other tanks, her sinking was inevitable. In contrast, part of the bow on Stockholm had been ripped away as she pulled out of the stricken liner, but by emptying water tanks the bow was raised almost to normal level. Being the nearest vessel to the disaster and still seaworthy, she assisted in rescuing survivors.

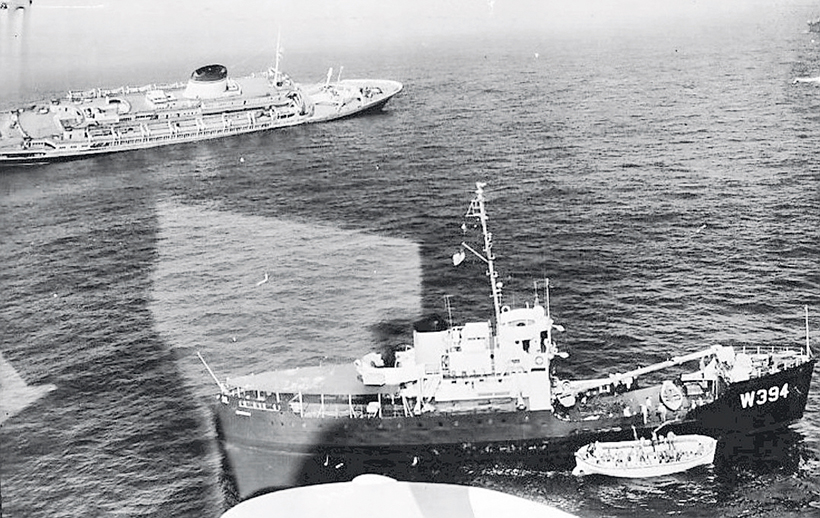

The 51st westbound crossing of Andrea Doria to New York in July 1956 ended in disaster. (Pic: United States Coast Guard, Public domain)

Help from other ships

Proving that the lifeboat capacity was only theoretical, only those on the starboard side of Andrea Doria could be launched because of the list. However, thanks to it taking several hours for her to go under (she capsized and started going down at 09:45 on 26 July 1956, over 11 hours after the collision) and, with other vessels nearby willing to help, including the French liner Île de France, most passengers and crew were rescued. In all 46 lives were lost from her, as well as five from Stockholm.

The supposedly unsinkable Andrea Doria listed on her starboard side before finally capsizing and sinking. (Pic: Harry A Trask/Public domain)

The incident and its aftermath were heavily covered by the news media. While the rescue efforts were both successful, the cause of the collision generated much interest in the media and was the subject of lawsuits. Largely because of an out-of-court settlement agreement between the two shipping companies during the hearings, no determination of cause was ever formally published.

Passengers in a lifeboat from the stricken Andrea Doria being rescued by another vessel. (Pic: Harry A Trask/public domain)

Ever since the sinking, Andrea Doria has lain about 160 feet down, a shallow enough depth to attract recreational wreck divers. However, strong currents and poor visibility make it a hazardous exploration and one that has claimed the lives of several divers.

This feature comes from the latest issue of Ships Monthly, and you can get a money-saving subscription to this magazine simply by clicking HERE

Previous Post

Vintage commercials enjoy a run to the seaside!

Next Post

Very collectable toy Y Type vans