Miniature oscillating-cylinder steam engines

Posted by Chris Graham on 2nd May 2021

Tim Armitage explains the appeal of miniature oscillating-cylinder steam engines; one of the most popular forms of engine for modellers.

Miniature oscillating-cylinder steam engines: A scientific instrument maker’s ‘A’ frame vertical oscillating engine from the 1880s.

The oscillating-cylinder engine was the most simple type of engine and predominated in the British toy engine market with Mamod, SEL, Bowman and others all making good, working models using these basic engines, historically fired with methylated spirit.

Almost all the many, late 19th and early 20th century German makers, such as Bing, Ernst Plank, Joseph Falk, Carette and so on, featured oscillating-cylinder engines at the less expensive end of their ranges of model stationary engines. The English scientific instrument and model makers also used oscillating-cylinder engines to very good effect in their ranges of demonstration models. This group of British engines are usually of great quality and elegance of design, making them beautiful and inspiring sculptures to enjoy in the home.

The 1872, two-cylinder compound oscillating-cylinder-powered paddle steamer Gisela on Lake Traunsee, in Austria.

Paddle steamer power

While oscillating-cylinder engines were popular for models, they were less useful in industries where a great deal of power was required. However, the compact nature of these engines worked well in paddle steamers. I have cruised on the last surviving oscillating engine-powered paddle steamer, the elegant Gisela that operates on Lake Traunsee, at Gmunden, in Austria. This was a valuable experience as I was able to watch this impressive engine at work. The fascination of this mesmerising vision was even more captivating than the spectacular scenery!

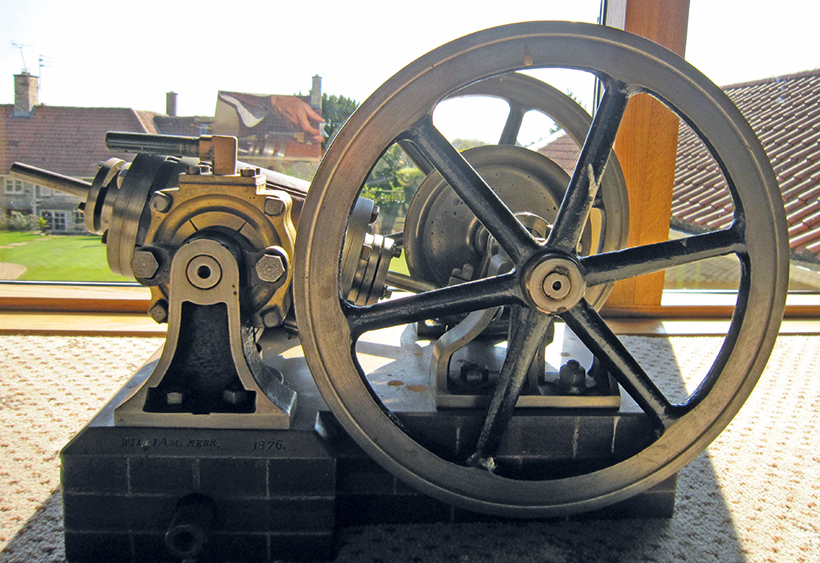

The 1876 engine by William Kerr.

The only, full-size oscillating-cylinder engine I’ve ever owned was a large and heavy, single-cylinder example signed by William Kerr in 1876. This very well-constructed engine mounted on a simulated brick base has two, 15in flywheels. The decorative plinth on which this magnificent machine sits may indicate that, although large enough to power a small workshop, it may still be a model. Possibly it was the maker’s own demonstration model for exhibition as a sales aid.

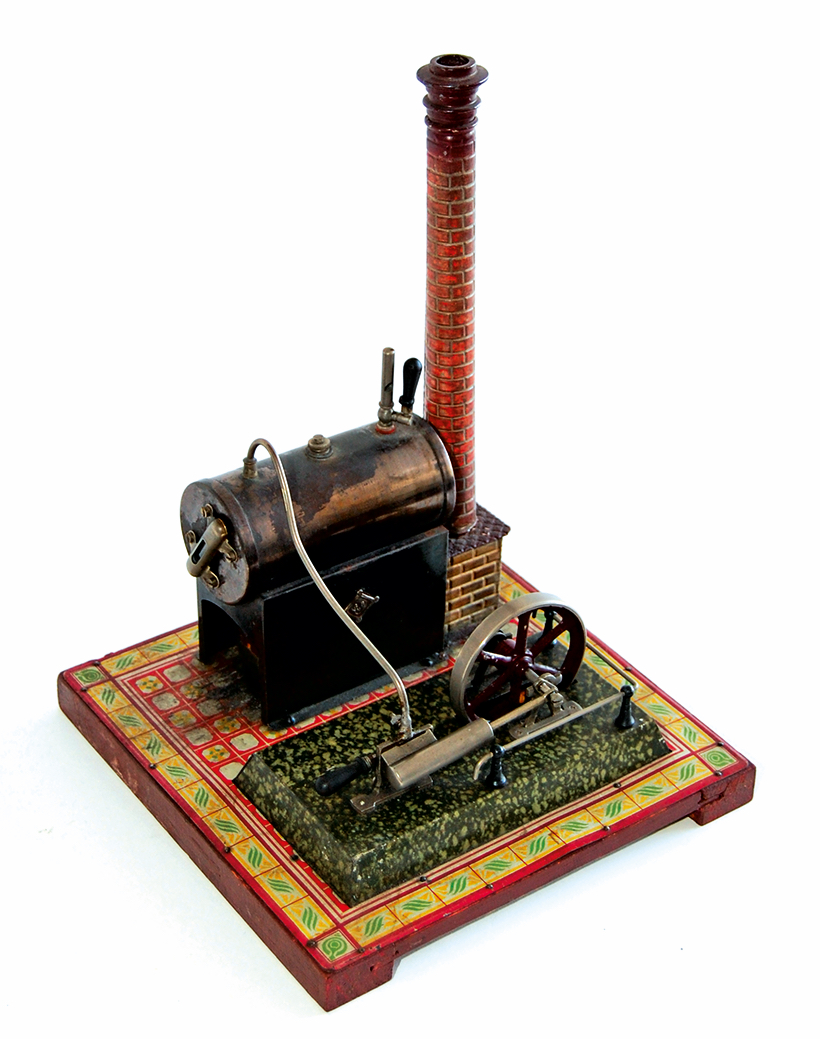

This 1920s Bing vertical stationary engine was bought when I was 16, and is still in my collection.

A lucky find!

The first engine I describe here is the very first vintage model steam engine to arrive in my collection. I bought it from an antique shop in Huddersfield when I was a student, in about 1960. This spirit-fired vertical-boiler engine is a product of Gebruder Bing of Nuremberg, and probably dates from the 1920s. The boilers on most of the German ‘toy’ engines are chemically-blued, rather similar to the process used on gun barrels.

A Bing horizontal engine from the 1920s.

The woman in the shop had just begun to apply Brasso to the boiler, but I stopped her just in time and only a half-inch square of the original bluing is missing. From a collector’s point of view, the original finish is of paramount importance but, if your interest lies in operating the engine, I suppose that originality doesn’t matter quite so much.

This superbly elegant, scientific instrument makers’ two-pillar overcrank-type oscillator (complete with haystack boiler) dates from the 1860s.

This engine cost me 15 shillings, which is probably equivalent to about £15 in today’s money. It, and the small horizontal engine shown here (also by Bing), represent great value today, being priced between at £40 and £100 on eBay and at toy swapmeets when they (I hope) start again.

A late-19th century two-pillar overcrank oscillator.

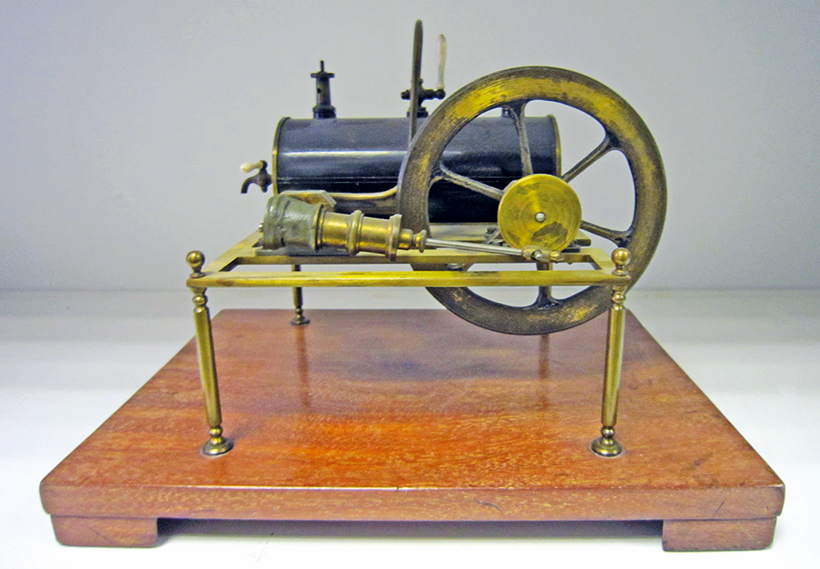

The next group of four engines are all commercial products manufactured in England by optical instrument makers, especially in London, from the mid-19th century until the early 20th century. These models weren’t mass-produced so didn’t sell in massive quantities worldwide like the German products.

A late-19th century scientific horizontal oscillating engine.

Beautifully-made

These fine models were hand-made using the highly-skilled techniques of scientific instrument makers. They are usually presented on polished mahogany bases, and often feature bone or ivory handles, as seen on the horizontal engine example. The brass is usually lacquered in exactly the same way as a microscope or telescope would have been. These engines, in my opinion, weren’t just sold as toys, but were also bought by gentlemen who wished to own working examples of the most up-to-the-minute technology.

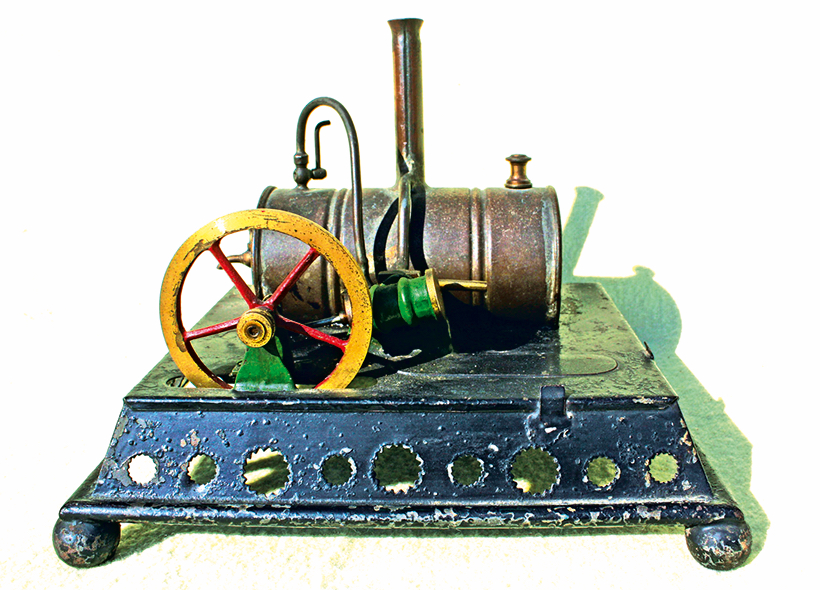

A late-19th century English donkey engine.

The final two engines are also English, commercially-produced products. They were marketed by the ‘Model Dockyard’ type of makers, and built using methods very similar to those used by the scientific instrument makers. However, they also utilised some mass-production techniques for some parts. For example, both these little donkey engines feature cast bases, made from cast iron in the case of the one with the ‘haystack’ boiler.

Another late-19th century English donkey engine.

The pre-war, German engines are readily available today. When I first began collecting old engines, they were only to be found occasionally on the collectors market, often being sold by the original owners, or their descendants. Now, half a century later, large, complete collections built up over a lifetime are offered for sale, some in the UK, but mainly in Germany, France and the USA. Today, the rarest and finest examples regularly sell for over £1,000, but lots of very desirable engines can still be bought at real bargain prices, in my opinion.

There’s a genre of cheaply-made, 19th century toy steam locomotives made in Birmingham – nicknamed ‘Birmingham Dribblers’ or ‘Birmingham Piddlers’ – notable for being of lightweight, pressed-tin construction, with very flimsy, pressed-metal boilers of brass, copper or even tinplate, in the very cheapest examples. This toy horizontal engine is a stationary engine to made ‘dribbler’ standards. Although the cheapest of the engines featured here, it came from a very grand source. Laurence John Cadbury died in 1982, and I bought most of the contents of his model engineering shed at an auction that took place at his grand, Bournville home.

For a money-saving subscription to Old Glory magazine, simply click here