The battle of Leyte Gulf

Posted by Chris Graham on 7th January 2022

Japan built the mightiest battleships ever, but WW2 gave them little chance to take advantage, until Leyte Gulf, as John Grehan explains.

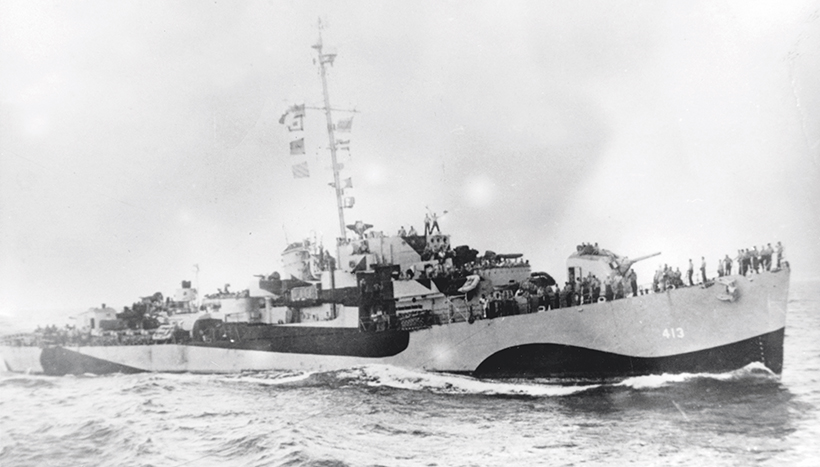

The battle of Leyte Gulf: USS Heermann laying smoke early in the battle. (Pic: USNHHC)

There had never been anything like them before. Displacing 72,000 long tons and stretching for 869ft, the Yamato class battleships, Yamato and Musashi, were the largest warships ever built. However, their most important attribute was not their massive size but their armament. They carried the largest naval artillery ever fitted to a warship and their main guns could fire a massive 18.1-inch (46cm) shell.

Not only were these triple guns the largest ever mounted on a warship, they considerably exceeded both the guns on any of their enemy’s battleships and the limitations imposed by the terms of the London Naval Treaty of 27 October 1930, to which Japan was a signatory. But entrenched in the belief of the so-called ‘Decisive Battle Doctrine’ (Kantai Kessen), the outcome of which would be settled by whoever possessed the mightiest warships, the Imperial Japanese Navy had constructed the formidable Yamato and Musashi, which entered service in 1942.

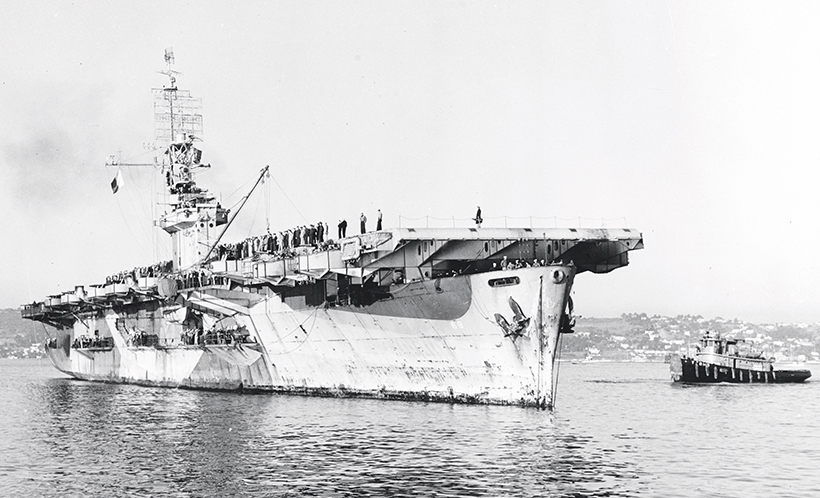

Some of the crew of USS Kalinin Bay watch as an explosion tears through USS St Lo after she was hit by a kamikaze off Samar, on 25th October. (Pic: NMUSN)

Throughout World War II the Imperial Japanese Navy sought in vain to entice the US and Allied fleets into that decisive battle where its big-gun battleships could be deployed with their greatest effect. As the months passed, the great battles of Midway and Guadalcanal were fought and lost, with the two Yamato battleships unable to intervene, their big guns unemployed. Due to the threat of US submarines and aircraft carriers, they spent most of their careers in naval bases at Brunei, Truk and Kure.

Yamato was severely damaged by a vessel a fraction of her size when she was hit by a torpedo from the US submarine Skate on Christmas Day 1943, necessitating a return to dock for repairs. It was a similar story for Musashi, which was struck by a torpedo from USS Tunny, forcing a return to Japan.

A few minutes after the initial contact, the Japanese force came into view. Almost immediately, Sprague ordered his ships to make smoke while the carriers turned into the wind and launched their aircraft. This photograph shows USS Gambier Bay and two destroyer escorts making smoke. The original caption notes that Japanese warships were ‘faintly visible on the horizon’. (Pic: USNHHC)

As the war in the Pacific entered its third year, it became apparent that Japan was doomed to lose all the conquests it had made in 1941 and 1942. Island after island had been recaptured or liberated by Allied forces and, by the autumn of 1944, they were poised to launch their assault upon the Japanese-held Philippines. Though the Japanese were defeated in the South Pacific, the assembly of a large Allied naval force to support the landings in the Philippines gave them hope that at last they could corner their enemy’s fleet and finally bring their big guns to bear.

OPERATION SHo-Go

For this operation the Japanese fleet was split into three separate forces. The first of these, the Task Force Main Body – the Northern Force – was to sortie from Japan and approach the Philippines from the north, stationing itself off the island of Luzon. This body, composed mainly of aircraft carriers but with few actual aircraft on board, would act as the ‘bait’, drawing the US covering forces – Admiral Halsey’s Third Fleet – away from protecting the American troops landing on the island of Leyte.

USS Kitkun Bay prepares to launch her FM-2 Wildcat fighters while, in the distance, shells are splashing near the escort carrier, USS White Plains. (Pic: USNHHC)

Once the Third Fleet had been enticed away from Leyte, Vice-Admiral Shoji Nishimura’s Second Striking Force, the Southern Force, would then bear down on Leyte which it was hoped would draw off the force supporting the landings, Admiral Kincaid’s Seventh Fleet. With the landing ships then unprotected, Vice-Admiral Takeo Kurita’s First Striking Force, the Centre Force, would easily be able to destroy the landing craft, leaving the Allied troops stranded until a counter-invasion could be launched to wipe them out.

But that, or something like it, was what Admiral ‘Bull’ Halsey was hoping for. He expected the Japanese to make a serious attempt to disrupt the landings and that would give him the chance to finish off what remained of the Japanese naval forces. Both sides were going to throw every available warship into what would prove to be the largest naval battle the world had seen.

The a John C. Butler class destroyer escort Samuel B. Roberts (DE 413) pictured in October 1944, just a week or two before the battle. She commissioned on 28 April, 1944, and was was stricken from the Naval Vessel Register on 27 November, 1944. (Pic: The USS Samuel B. Roberts Survivors Association)

HALSEY DECEIVED

On 24 October 1944 the Japanese Southern Force was located in the Sulu Sea and Vice-Admiral Kinkaid sailed rapidly south with the Seventh Fleet to counter the approaching enemy. The Central Force was also spotted, in the Sibuyan Sea, and was attacked by carrier-borne aircraft of the Third Fleet. The Japanese fought back and both sides lost ships.

Losses were greater among the Imperial Japanese Navy, particularly as one of those that was sunk was one of the most important ships in the Central Force, Musashi. Despite her size and speed, the thickness of her armour and the power of her guns, repeated strikes by US aircraft completely overwhelmed her.

The commander of the Central Force, Admiral Kurita, withdrew to reorganise his force, which had scattered under the ferocity of the American attacks. From the reports of his returning pilots, which proved to be more than a little exaggerated, Halsey believed that the Centre Force had been so severely crippled that its withdrawal meant it had abandoned its mission and was in full retreat.

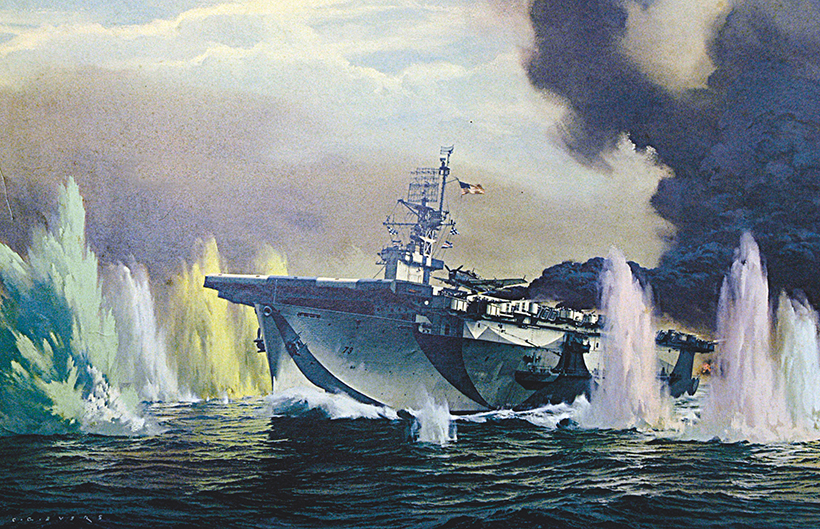

A painting by CG Evers depicting Gambier Bay’s final hour. Gambier Bay was the only American aircraft carrier sunk by enemy surface gunfire during World War II. (Pic: United States Naval Institute)

Halsey, though, was concerned that the main Japanese carrier force, which US intelligence had informed him had left Japan, was nowhere to be seen. That was until late on 24 October.

This Northern Force was the ‘bait’ to draw the Third Fleet away from Leyte, and Halsey swallowed the bait, hook, line and sinker. Taking every ship he could muster, he set off as quickly as he could after the Northern Force. With the Seventh Fleet facing Admiral Nishimura’s Southern Force in the Sulu Sea, the ships of the landing force were left with no powerful force to protect them, just as the Japanese had hoped.

BATTLE OFF SAMAR

Musashi might have been lost, but her sister, Yamato was still very much afloat, and the super-battleship bore down on three escort carrier groups of the Seventh Fleet, call-signs Taffy I, 2 and 3, with their destroyer escorts. In theory they stood little chance against Kurita’s battleships and cruisers.

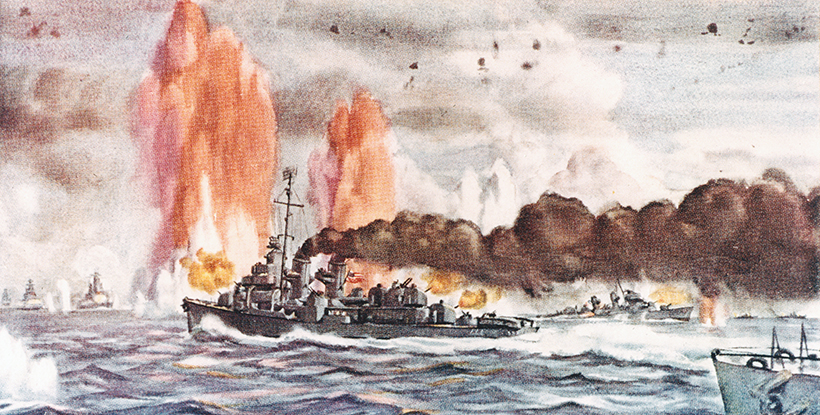

A watercolour by Cdr Dwight Shepler depicts the counterattack by the escort carrier group’s screen, involving Dennis and Raymond intervening and trying to cover the carriers with smoke to try and distract the Japanese cruisers. (Pic: USNHHC)

Taffy 3, the most northerly group and the closest to the San Bernardino Strait, sighted the approaching Japanese warships first, on 25 October. Almost immediately, Rear Admiral Clifton Sprague ordered his ships to make smoke while his carriers turned into the wind and launched all their aircraft, irrespective of their state of readiness. While they were doing this, the big guns of the Japanese ships roared. Sprague later reflected that, ‘It did not appear any of our ships could survive another five minutes.’

Advancing with Yamato were the battleships Nagato, Kongo and Haruna, the heavy cruisers Chokai Haguro, Kumano, Suzuya, Chikuma and Tone, along with two destroyer flotillas. The battleships opened fire almost as soon as the American ships were spotted, Yamato firing first at a distance of 35,000 yards. It was the first time the 3,220lb shells of the super-battleship had been propelled at an enemy surface target from the 70ft-long barrels of its monstrous guns.

The escort carrier Kalinin Bay arriving at San Diego, California on 25th November, 1944, for repairs to the damage she suffered at Leyte Gulf. (Pic: USNHHC)

The enormous enemy shells began splashing around Sprague’s comparatively small ships. Tremendous splashes, vibrantly coloured by dye, sprouted along the wakes of the American vessels. The slow-moving escort carriers could never hope to outrun the fast enemy battleships. There was only one alternative to running, and that was staying to fight, and at 0716 Sprague ordered his destroyers to carry out torpedo attacks. With Johnston in the lead, followed by Heermann and Hoel, the three destroyers turned and raced towards Kurita’s huge warships.

DESTROYERS ATTACK

Johnston managed to damage the heavy cruiser Kumano with a torpedo strike, which cut off part of her bow, but was in turn heavily damaged by 6- and 14-inch shells. Hoel fired at, and missed, the battleship Kongo, and was also hit multiple times. For a while, she was boxed in by Japanese battleships and cruisers, all of which fired at her. Heermann then entered the fray, launching torpedoes at the Japanese heavy cruiser Haguru, but Haguru evaded the torpedoes and fired multiple salvos at the destroyer, which all missed.

Moving beyond the Japanese cruiser division, Heermann came upon the battleships Kongo, Yamato and Nagato, firing her remaining torpedoes and 5-inch guns at Kongo. The destroyer then quickly came about and moved to a screening station on the starboard flank of the carriers. Despite the intensity of Japanese fire, the only damage aboard Heermann had been caused by shell fragments. The strike suffered by Kumano caused her speed to be reduced to 16 knots.

The destroyer Hoel was hit repeatedly as she attacked, being riddled by some 40 holes from 5-inch, 8-inch and 14-inch shells. At 08:55 she sank while her crew were trying desperately to repair the battle damage. This view of Hoel is dated 3 August, 1944. (Pic: NARA)

Throughout this period the Japanese ships had come under almost continuous assault from the aircraft of Taffy 3, as well as Taffy 2. Just after the Japanese force had been sighted by Taffy 3, Admiral Stump had his available TBM Avengers rearmed with torpedoes or 500-pound bombs capable of damaging capital ships. As Taffy 3 was being pursued, Stump closed the distance to Sprague’s task unit and was able to launch three strikes during the battle.

By 0738 on 25 October the foremost cruiser was no more than 14,000 yards behind the carrier St Lo, while another cruiser and what appeared to be a large destroyer moved up to within 12,000 yards of the task unit and delivered repeated full broadsides at the American ships.

Kurita had not assigned his captains any specific targets, each being permitted to take advantage of whatever situation presented itself. But the Japanese rate of fire was very slow – more than a minute between salvos – which gave even the clumsy and slow American escort carriers time to manoeuvre.

A Japanese destroyer firing at the aircraft from Taffy 3, as photographed by one of USS White Plains’ aircraft. (Pic: USNHHC)

At 0740 Sprague ordered his destroyers to make a second torpedo attack. Johnston attacked first, firing a full salvo at one of the heavy cruisers. She received heavy damage but continued to fire her guns at ranges down to 5,000 yards.

Hoel was next, launching a half-salvo at one of the battleships at a range of 9,000 yards. Almost immediately, she was hit, and her port engine and steering engine were put out of action but, steering by hand, Hoel continued to fire her guns at the battleships and cruisers which were then either side of her. A few minutes later, Hoel fired another half-salvo of torpedoes, striking one of the cruisers at 4,000 yards.

Japanese shells falling short of USS Kalinin Bay; smoke from the enemy warships can just be seen in the distance. (Pic: USNHHC)

Astonishingly, it was not until 0750 that the Japanese ships managed to land a blow on any of the escort carriers, but soon the latter started to take hits. But by this time Kurita had had enough. Most of his cruisers had been sunk or disabled, and, with the aircraft from all three of Kinkaid’s task units unrelenting in their attacks, Kurita simply gave up and withdrew.

USS Heermann (DD-532), a Fletcher class destroyer, was more fortunate than many of the ships involved at Leyte Gulf, as she survived the battle and the war, and this photograph of her is dated December 1959. Commissioned from July 1943 to June 1946, she was recommissioned on 12 September, 1951, decommissioned in December 1957, and transferred to Argentina in August 1961, not being scrapped until 1982. (Pic: USNHHC)

The final toll of the Battle off Samar saw three Japanese heavy cruisers sunk and the other three damaged, along with one destroyer. For all their efforts and their big guns, the Japanese sank two US destroyers, a destroyer escort, and an escort carrier by gunfire, and another US escort carrier was hit and sunk by a kamikaze. The biggest of the guns on the US ships? They were just 5-inch.

For a money-saving subscription to Ships Monthly magazine, simply click here