The record-breaking Normandie

Posted by Chris Graham on 6th July 2021

Mark Berry charts the all too short life of the record-breaking Normandie, surely one of the greatest transatlantic liners ever built.

The record-breaking Normandie, one of the most powerful steam turbo-electric-propelled passenger ships ever built

Normandie, the French ocean liner built for the French Line, entered service in 1935 as the largest and fastest passenger ship afloat, and crossed the Atlantic in a record time of four days and three hours. She remains the most powerful steam turbo-electric-propelled passenger ship ever built, yet she enjoyed a all too short career.

On 29 October 1932, while hull number 534, to become the famous RMS Queen Mary, was unfinished and abandoned on the slipway in Clydebank, hull number T6 sat ready for launch in St Nazaire, France. Both born into the Great Depression, these two ships were to set the tone for transatlantic travel in the 1930s, and T6 was about to become Normandie.

Conceived by Compagnie Générale Transatlantique as an evolution of the successful liner Île de France, Normandie was to be ‘France afloat’, acting as a showcase to reflect the best of the nation, its culture, its cuisine and its science. In spite of prevailing worldwide economic woes, the French Government heavily subsidised the building of the ship, which, at $60 million, cost twice as much as Queen Mary.

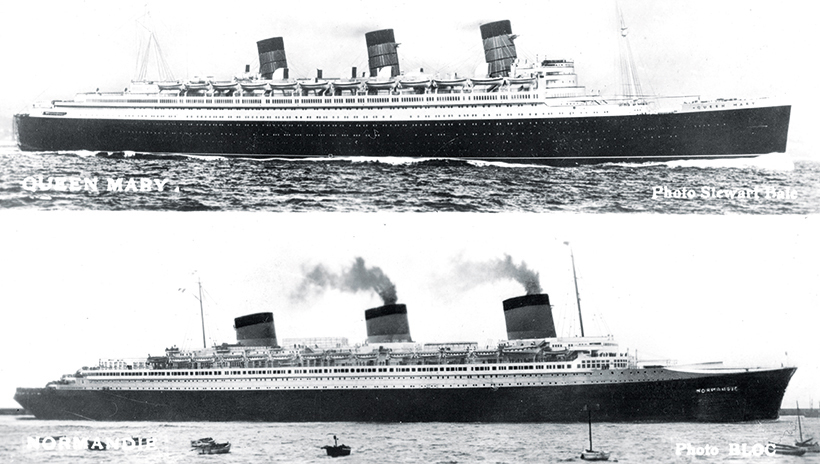

A contemporary postcard showing the profiles of Queen Mary and Normandie, the two great liners of their era.

This huge expenditure must be considered within the context of the battle for prestige and supremacy on the North Atlantic. The French and British were far from the only players. Germany’s Bremen and Europa, Italy’s Rex and Conte de Savoia were all built during this period. They were ships of state, vying for market share, with glamorous interiors, technological advances and, of course, speed. The Blue Riband, accolade for the fastest Atlantic crossing, was very much in the minds of those who built and operated these liners. Size was the final factor. To run the biggest liner gave as much kudos to a shipping line in the 1930s as it had in the 1890s, and Normandie was the biggest by a margin, measuring 1,030ft by 117.8ft and 79,280grt.

Technically, the ship broke new ground on a number of fronts. The Russian engineer and designer Vladimir Yourkevitch (born 1885), learnt his craft designing cruisers for the Russian navy, which was being modernised after the defeat by Japan in 1905. The streamlined concepts he brought to the design of submarines produced hull forms well ahead of their time. After the Russian Civil war, Yourkevitch relocated to France and began work for Penhoet, St Nazaire, and in 1929 became involved in the design of T6.

His design, which incorporated a bulbous bow, beat 25 other designs and was adopted for her construction. Funnel uptakes ran up the sides of the ship rather than the centreline. This departure from convention had also been used on the French Liner L’Atlantique of 1930. On Normandie it allowed an uninterrupted flow of public rooms and spaces which did not have to be arranged round large central voids for the uptakes. An uninterrupted vista of 700ft led down the grand staircase through lounges and salons, almost the entire length of the ship.

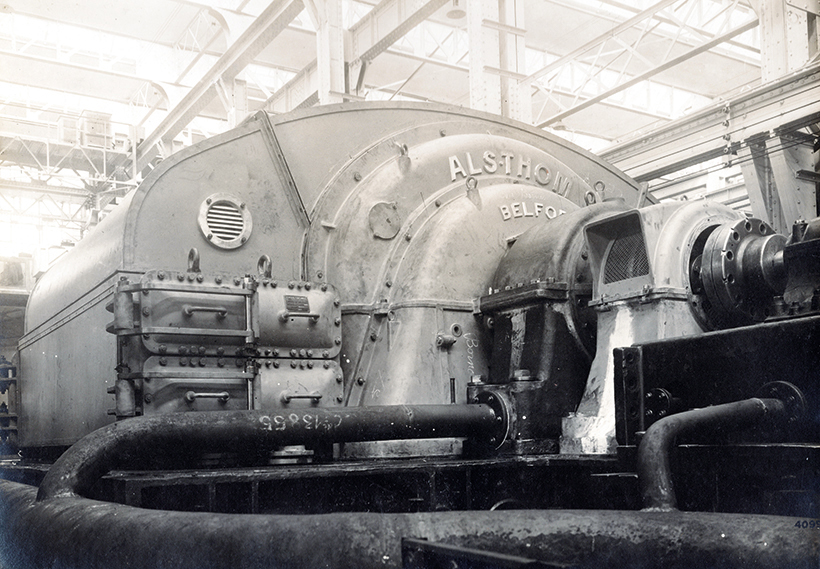

One of Normandie’s huge alternators. She had installed power totalling 160,000hp.

The exterior of Normandie was another departure from the norm. There was no cluttering of her decks with ventilators or unnecessary deck fittings and winches, as these were hidden within the hull or beneath the streamlined whaleback with its adjoining breakwater, on the foredeck. The foremast was situated above the bridge rather than on the deck, further enhancing Normandie’s clean lines. Of her three huge raked funnels, the rear was a dummy and housed the dog kennels, as well as providing ventilation for the interior of the ship.

For propulsion, quadruple three-bladed screws were linked to a massive turbo electric power plant producing 165,000shp, and 33 oil-fired boilers were linked to six small and four large turbines, which drove four turboalternators producing 33,400kw of electricity. Four huge electric motors drove the screws.

The interior of the ship was radically modern. Although Tourist and Third class were by no means lacking in comfort or appointments, the ship was geared to the premier class experience for First class passengers. The Art Deco movement of the late 1920s and early 1930s, arising from a group of radical artists and designers, found a stage at the 1925 Exposition Internationale des arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes in Paris, and heavily influenced the interiors of the new French ship of state.

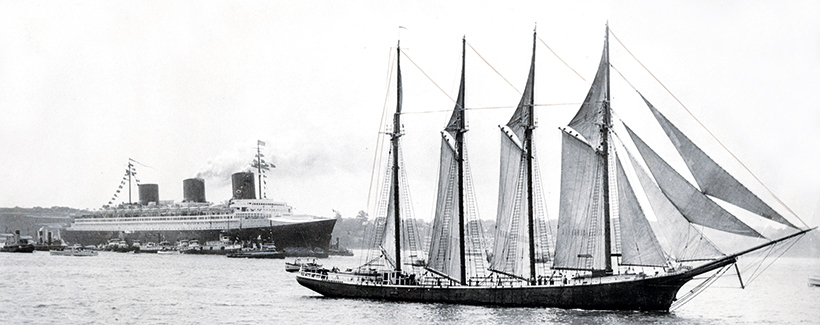

Normandie making her maiden arrival in New York.

Companies such as Lalique (glassware), Aubusson (carpeting and tapestries), and Christofle (silverware) were involved in fitting out the ship. Designers such as Raymond Subes, a metal worker and furniture maker, and Jean Dupas, an artist and designer, were brought in to work on the ship. Dupas was responsible for the huge First class dining salon, longer than the hall of mirrors at Versailles, and three decks in height. This amazing room, the largest at sea, was clad in glass, with 12 Lalique lighting towers and 38 illuminated columns. The room was accessed by 20ft-high doors adorned with bronze medallions depicting scenes from the Normandie region.

Public spaces in First class also included a grand lounge, a winter garden with exotic plants, caged birds and a fountain, and indoor and outdoor pools. There was a full-sized theatre together with a children’s playroom. The café-grill at the rear of the superstructure offered a fine dining experience, and at night the furniture was moved to create a dancefloor, and the room became a nightclub.

Before the ship had her first refit in 1936, the café-grill opened onto a large open terrace overlooking the stern. During the refit, this lovely open space was sacrificed to accommodate a rather ungainly-looking tourist lounge, which to many rather spoilt the ship’s lines. At the same time, the original three-bladed propellers were replaced with four-bladed ones to address vibration issues.

The First Class Dining Room.

Normandie carried three classes of passenger. In addition to 848 First or Cabin class, there was provision for 670 Tourist class and 454 Third class. As with all three-class ships of the day, each class had its own separate self-contained areas, with dining rooms, lounges, smoking rooms and bars and of course separate cabin spaces.

The peak of luxury were the grand luxe suites, Rouen, Caen, Deauville and Trouville. These apartments offered bedrooms and bathrooms for three couples, together with salon, private dining room, pantry and bedroom space for children and servants. Deauville and Trouville had their own private deck space. These suites attracted celebrities such as Cary Grant, Marlene Dietrich and Walt Disney, who appreciated the privacy, level of service and French Style that Normandie’s deluxe service offered.

On 29 October 1932, T6 was launched and christened Normandie by Madame Lebrun, France’s First Lady, at the Chantiers de Penhoet yard. There then followed a long period of fitting-out, during which the cavernous interiors became probably the most lavishly appointed spaces ever to go to sea.

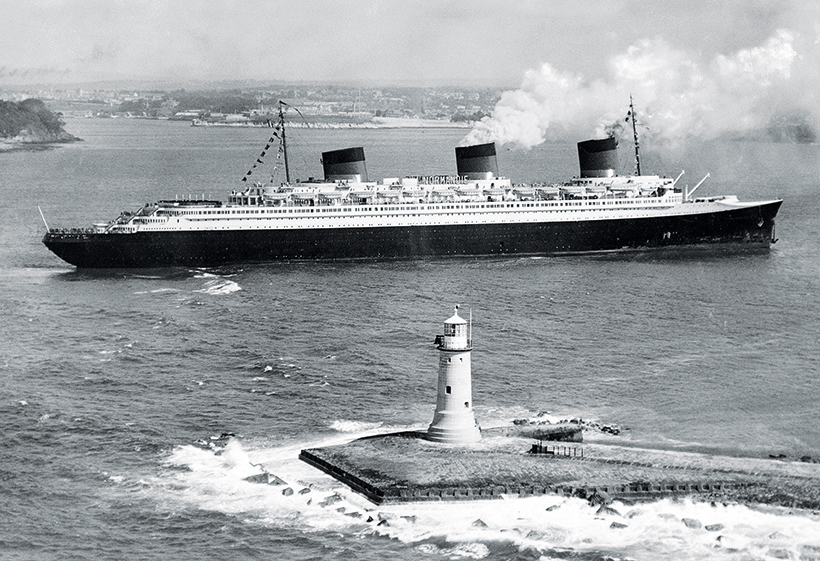

Normandie entering Plymouth Harbour after the return leg of her maiden voyage.

At her trials she performed well, although vibration was a problem at high speed. She was formally handed over by the builders to her owners on 29 May 1935, and preparations began for the maiden voyage, which began at Le Havre.

In command was 54-year-old Captain Rene Pugnet. Having joined CGT in 1907, he commanded a crew of 1,339 men and women on Normandie, who in turn served 1,014 passengers on this maiden crossing. President and Madame Lebrun were on board, with many other invited guests and dignitaries. CGT would earn no revenue from this trip, but there were huge public relations compensations.

Across the Atlantic

From Le Havre Normandie steamed to Southampton, and then headed out into the Atlantic, making the crossing of 2,907 miles in a record four days, three hours and two minutes, averaging 30.1 knots, and taking the Blue Riband from the Italian Line’s Rex. A rapturous reception awaited the ship as she steamed into New York, proceeded up the Hudson River and docked at the French Line Pier 88. The ship was opened to the public, and journalists waxed lyrical about the new French wonder. As an aside, most of the First class ashtrays, branded with the ship’s name, were stolen during this period. The replacements did not carry the name of the ship, and the originals are now highly collectable.

A painting of Normandie as she arrives at New York 1935, by Harley Crossley.

The ship broke the eastbound record on the return leg, calling first at Plymouth to unload some passengers and the mail, then heading to Southampton and back to Le Havre. Normandie traded the Blue Riband with Queen Mary, which finally entered service on 27 May 1936, until the outbreak of war in 1939.

There is no doubt that during her all too brief career, Normandie did not achieve her financial potential. Some passengers found her interiors just too radical and intimidating in their grandeur. Queen Mary felt more like a country house in comparison, and many British and American travellers preferred this more traditional feel. Those who did travel on Normandie, however, certainly in first class, were treated to a level of service and gastronomic delight that has probably never been equalled.

Normandie undertook two cruises to Rio in 1938 and 1939, organised by the Raymond Whitcombe Travel Agency, crossing the equator and into tropical waters for the first time. She visited Nassau, Trinidad and Martinique, as well as Rio, on a 29-day itinerary, with prices starting at $435. These sunny holiday cruises were soon to become a memory, however, as the situation in Europe spiralled towards conflict.

Normandie left Le Havre for the last time on 23 August 1939, carrying 1,417 passengers to New York. On 1 September, while she was docked in Manhattan, war was declared and Normandie was ordered to remain in port.

Two years passed, most of her crew returned home and the now nearly empty and lifeless ship lay at her berth. Other liners, such as Queen Elizabeth and Queen Mary, carried out troop-carrying duties, but Normandie waited in New York, with a skeleton crew keeping only essential services on board running.

In December 1941 she was taken over by the US Government and renamed USS Lafayette, and work began converting her to a troop ship. The famous liner probably had the largest troop-carrying capacity of any vessel of the time, and was seen as vital to US troop moving capacity.

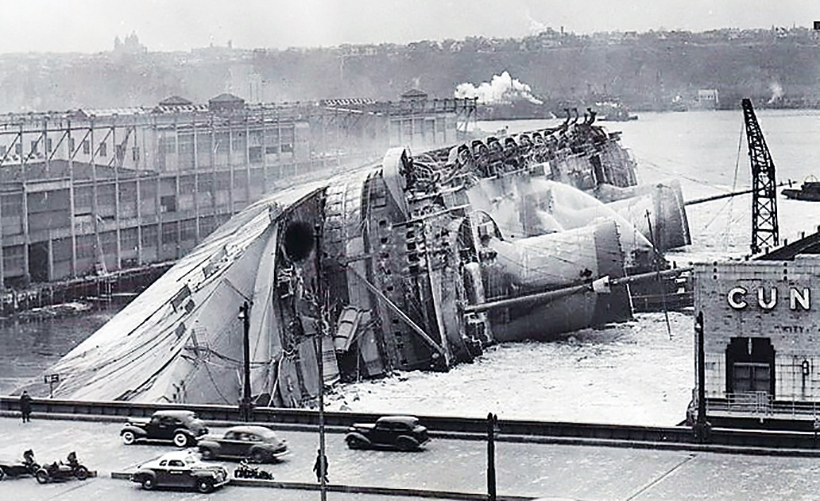

A sad end to an iconic ship; Normandie on her side at Pier 88, New York, in February 1942.

However, this was not to come to pass. During December 1941 and into early 1942 work on the removal of furniture and fittings began, and the necessary structural alterations within the hull were made. On 9 February 1942 a welder, removing one of the light stanchions in the grand salon, accidentally set fire to a stack of kapok life preservers which were stored nearby.

The end was tragic, as the fire mercilessly took hold of the ship’s structure and consumed the large areas of woodwork and decoration which had not yet been removed. The ship’s sophisticated fire protection system had been disconnected, and the New York Fire Dept’s hoses did not fit the ship’s water inlets.

Vladimir Yourkevitch, who was at that time in New York, pleaded to be allowed on board to open the sea cocks and flood the ship on an even keel, but he was overruled, and in the early hours of the next day, unstable owing to thousands of gallons of water hosed on to her, Normandie tipped over onto her port side alongside her dock, and her seagoing career was ended.

Beyond saving

The salvage process was initially geared to righting the ship with the intention of putting her back into service. But the long process of cutting away the superstructure, plugging every underwater porthole, door and opening, and pumping her dry proved to be in vain.

Her hull was resting on a rocky outcrop beneath the harbour mud, and as she pivoted and moved with the tides, considerable damage was caused to her plating and structure, and she was declared to be beyond repair. Although now upright, the ship was towed away in October 1943 to be scrapped at Port Newark. By December 1948, Normandie, the Ship of Light, was gone.

For a money-saving subscription to Ships Monthly magazine, simply click here