Tiger class light cruisers

Posted by Chris Graham on 29th June 2021

Conrad Waters recounts the history of the Royal Navy’s three Tiger class light cruisers, which were first conceived during World War II.

Tiger class light cruisers: Blake, early in her career. She was the third and final member of the Tiger class, and the last RN cruiser to be built. (Pic: Author’s collection)

On 8th March, 1961, a short ceremony held at Fairfield’s shipyard at Govan on the River Clyde saw the new Royal Navy cruiser HMS Blake commissioned into the fleet. The third of three Tiger class light cruisers, she had first been laid down nearly two decades previously during the height of World War II. The Tigers were the last Royal Navy cruisers, while Blake was the final all-gun-armed cruiser completed anywhere in the world.

The Tiger class traced its origin to a series of ships ordered under the Royal Navy’s wartime construction programmes in 1941 and 1942. The new cruisers were initially intended to be modified variants of the existing Fiji or Colony class, slightly updated to take account of the lessons of the conflict. Three of these ships, Swiftsure, Superb and the Canadian Ontario, were completed on the basis of the original design between 1944 and 1945. Another ship, Hawke, was scrapped at the end of hostilities, before she had been launched, while others were cancelled before work had even begun.

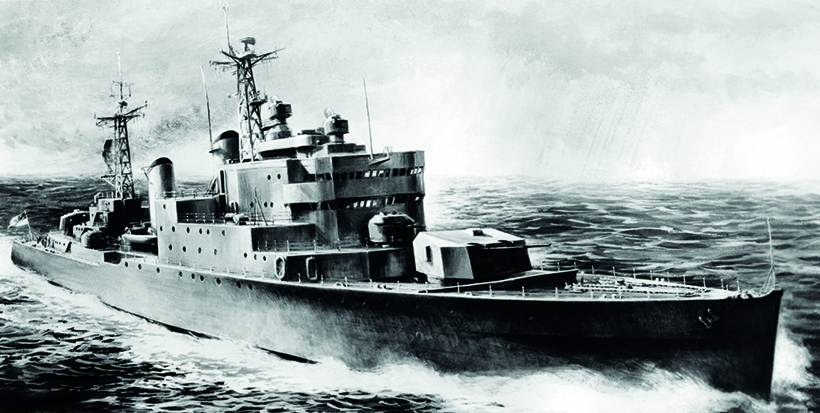

An official image released showing the revised Tiger class design. The class was based on modernising war-built hulls with a new superstructure and equipment. (Pic: Admiralty)

This left three ships which had all been launched by the end of 1945, but which were still some way from completion. None were immediately needed now that the war was over, and funds for the work necessary for their completion were lacking as Britain tried to rebuild its shattered economy. Equally importantly, there was a growing recognition that the existing design had been rendered obsolete by wartime advances in armament and other technology.

Between 1946 and 1948 work on the remaining ships effectively ground to a halt as it became apparent that neither the money nor the equipment required to complete the new cruisers would be available in the foreseeable future. Although serious consideration was given to terminating the entire programme, a compromise was reached. All three ships would be laid up in an incomplete state with a view to resuming construction with the most advanced armament as was practical as soon as economic conditions permitted. The delay proved to be lengthy. Competing priorities, particularly for new anti-submarine vessels, and difficulties in agreeing and designing the armament served to postpone the resumption of building activity for many years. It was not until 1954 that it was finally agreed to complete the ships to a radically new design. As eventually completed, the Tiger class cruisers were compared with putting ‘new wine into an old bottle’. The use of the existing hull, rather than that of the cramped Fiji class vessels, and the retention of the existing main machinery represented major limitations.

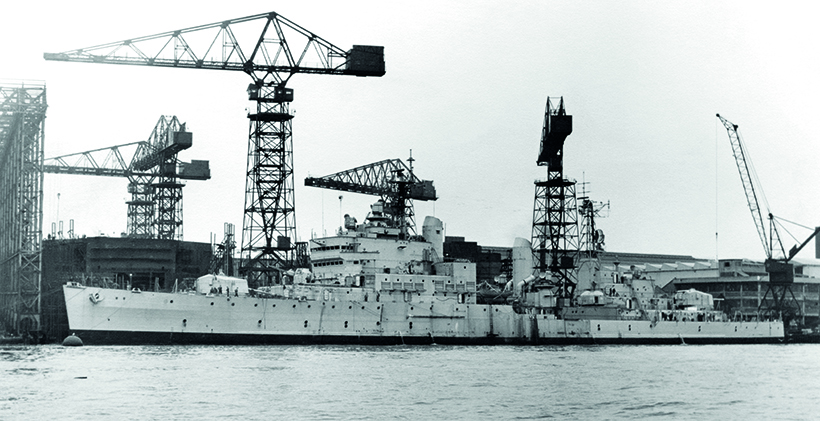

Lion nearing completion at Swan Hunter’s shipyard on the River Tyne in early 1960. She had first been laid down by the Scotts yard on the Clyde nearly 18 years previously. (Pic: Author’s collection)

Otherwise, the modernisation was very extensive. It involved stripping out all the superstructure, bridge and gun supports and replacing most of the existing internal fittings.

The most significant changes were the installation of new weapons and associated fire control systems. The highly automated main armament comprised four 6-inch QF Mk N5 guns mounted in two twin Mk.26 dual purpose turrets capable of 360 degrees rotation. Each of the new guns could fire up to 20 rounds per minute. This provided the Tigers with broadly similar firepower to their wartime predecessors equipped with nine of the older 6-inch Mk XXIII guns.

This profile view of Tiger shows the class’s overall layout, including the two twin turrets forward and aft for the main armament, and the three smaller mountings for 3-inch guns. (Pic: Author’s collection)

Secondary armament also comprised a new weapons system, encompassing six 3-inch QF Mk N1 guns mounted in three twin Mk.6 mountings. Primarily intended for anti-aircraft use, each gun had an impressive rate of fire in the order of 100 rounds per minute. Both main and secondary weapons were directed by the radar-equipped MRS 3 fire control system, which was based on technology used in the US Navy’s equivalent, Mk.56. Each gun mounting had its own radar-equipped director, meaning that it was possible to engage up to five targets at the same time.

Internally, the ships benefitted from modern command and control facilities and a limited degree of protection against nuclear, biological and chemical contamination. Crew facilities were upgraded from traditional ‘broadside messing’ to the latest cafeteria style arrangements. It was claimed that, on completion, the new cruisers would be superior in habitability to any other ships in the fleet, but this seems to have been a little disingenuous. Squeezing so much new equipment into what was always a ‘tight’ design meant that the Tigers were regarded as rather cramped ships.

The Tiger class’s main armament of four, 6-inch QF Mk N5 guns mounted in two twin Mk 26 dual-purpose turrets, gave the ship a total maximum rate of fire of up to 80 rounds every minute. (Pic: Author’s collection)

Entry into service

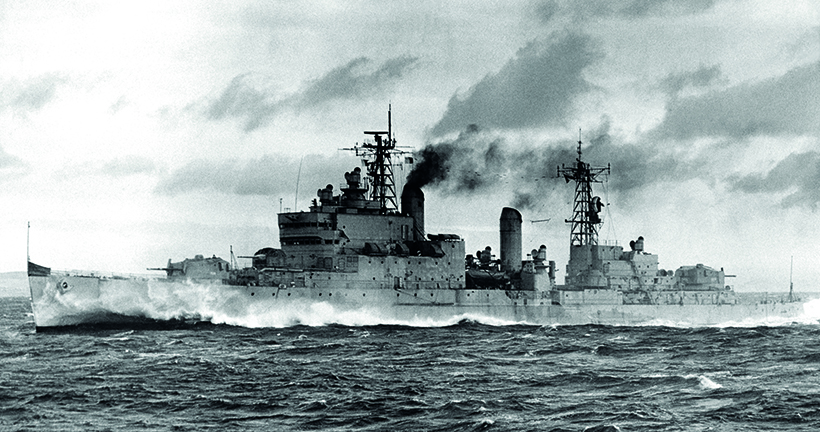

The final decision to complete the Tigers was followed by a period of intensive activity as the three cruisers were first partly dismantled and then rebuilt. Accordingly, it was not until early 1959 that the lead ship, Tiger herself, was ready for delivery from the famous yard of John Brown & Company. Her sister, Lion, followed her into service from Swan Hunter on the Tyne in mid-1960, with Blake completing the class the following year.

Intended to provide close-range cover and anti-aircraft support for carrier task groups and convoys, the Tiger class entered service just as the traditional cruiser was beginning to lose its relevance to modern naval operations. New missile-armed ships in the form of the County class destroyers were already on the horizon, and these were regarded as being more effective in the role for which the Tigers were designated. The first of these, Devonshire, commissioned only a year after Blake had been delivered. By 1963 the Tigers were the only remaining operational cruisers in the Royal Navy fleet.

Tiger during builder’s trials on the River Clyde, early in 1959. She commissioned on 18th March, 1959. (Pic: Admiralty)

The result was that the new Tigers quickly became ships searching for a meaningful purpose. Their complex main armament suffered from a significant number of initial teething troubles and – given that the missile was seen as the way forward – there was only limited incentive to achieve a comprehensive solution. The cruisers also required large and technically proficient complements at a time when Royal Navy crewing levels were under pressure.

As a consequence, Tiger and her sisters had only relatively short careers as conventional cruisers. Notably, Blake spent only one commission in her original configuration before being transferred to reserve in 1963. The other two ships spent much time away from home waters, playing an important role in covering Britain’s final withdrawal from empire. Both cruisers were particularly active during the confrontation with Indonesia over the future status of Malaysia. Lion was also present at the celebrations marking the independence of several former colonies. Tiger earned her moment in the spotlight late in 1966, when she hosted high-profile talks between Prime Minister Harold Wilson and Ian Smith, leader of what was then known as Rhodesia.

Tiger in the Far East in 1962. Along with her sister, Lion, she was to play an important role in stabilising the region during Britain’s transfer of its former colonies to independence. (Pic: Author’s collection)

The African country had unilaterally declared independence in an attempt to maintain white minority rule, but many years were to pass before a resolution was achieved. On conclusion of the meeting, Tiger returned to Devonport to pay off, leaving the Royal Navy without a cruiser in commission.

An evolving mission

Questions over the Tiger class’s longer term relevance were being asked even as they were being completed. However, the need to deploy a new generation of large anti-submarine helicopters across the fleet resulted in the emergence of a potential new mission. Early in 1964 it was decided that all three ships would be converted to specialist helicopter cruisers. Blake was to the first to enter dockyard hands for the reconstruction work to begin.

An impressive view of Lion at speed in the early 1960s. She represented Britain at a number of independence ceremonies during this period. (Pic: Admiralty)

The conversion involved extensive changes to the ships aft of the funnels, with the 6-inch turret in ‘X’ position being replaced to make space for a helicopter flight deck and hangar. It was originally intended to retain all three 3-inch gun mountings. However, a need to extend the hangar forward to house the new larger Sea King helicopter in place of the originally-intended Wessex saw two of these being replaced by more compact Seacat surface-to-air missile launchers.

The new arrangements allowed a flight of four anti-submarine helicopters to be embarked. The reconstruction also included enhancements to the suite of radar equipment and a new combat management centre. The enhanced command facilities this provided proved particularly useful when the subsequent decision to phase out the Royal Navy’s aircraft carriers resulted in a shortage of ships suitable for leading task force operations.

Tiger soon after completion. The Royal Navy will not see her type again. (Pic: Admiralty)

All this came at a price, with Blake’s modernisation taking far longer and costing much more than initially envisaged. Completion of the work was further delayed by two fires. Entering dockyard hands in April 1965, it was only in 1969 that Blake returned to the operational fleet. One of her first duties was to carry out landing trials of the Harrier jump jet on board her helicopter deck, demonstrating the inherent potential of the revised design.

Tiger followed Blake into dockyard hands, being recommissioned in 1972. The cost of the work was over £13 million, more than she had originally cost to complete. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Lion’s proposed modernisation was cancelled and she was ultimately sold for scrap in 1975. She had been in operational service for only five and a half years, less than a third of the time she had spent under construction.

Blake, in helicopter cruiser configuration, entering Portsmouth Harbour for the last time, in December 1979. The first Hunt class MCMV, Brecon, can be seen in the background. (Pic: Admiralty)

Conclusion

The two remaining Tigers served through much of the 1970s, leading a number of ‘out of area’ global deployments that followed the Royal Navy’s retreat to a largely NATO-focused role. Both were present at the 1977 Silver Jubilee Fleet Review, although Tiger was decommissioned the following year. Blake followed at the end of 1979, largely due to the difficulty of finding the large crew needed to keep her in commission.

The crisis that followed Argentina’s invasion of the Falkland Islands in April 1982 brought the prospect of a return to service. However, it was ultimately determined that the war would be over before the elderly cruisers could be refitted. Blake was sold for demolition later the same year but it was not until September 1986 that Tiger departed on her final voyage to the breaker’s yard in Spain.

A Sea King helicopter coming in to land on Tiger, in 1973. The ship’s reconstruction allowed her to operate up to four helicopters of the type. (Pic: Admiralty)

All in all, it is difficult to see the Tigers as being more than a qualified success. The long delay in their initial completion meant that the concept of the gun-armed cruiser was already obsolete by the time they commissioned. The subsequent reconstructions of Blake and Tiger proved to be long and expensive, albeit ensuring they had longer careers than might otherwise have been the case. However, they provided useful service during the years of imperial retreat and, in their helicopter cruiser configuration, helped pave the way for the Invincible class light carriers. Their passing marked the end of a type that will not be seen again.

For a money-saving subscription to Ships Monthly magazine, simply click here