1917 AEC Y-type lorry saved and becomes film star!

Posted by Chris Graham on 31st January 2023

Zach Stiling meets Seb Marshall to get the story of his saved and superbly restored 1917 AEC Y-type lorry; a veteran of the Great War.

1917 AEC Y-type lorry: Viewed from the front, the vehicle has an imposing presence.

The Associated Engineering Company (AEC) was barely out of its swaddling clothes when Europe went to war in 1914, but its rise to prominence had been more or less instant, owing to the stature of its parent firm, the Underground Electric Railways Company. The creation of AEC was just the latest in a very convoluted series of dealings in which various competing public-transport operators in London were trying to get the better of one another.

A three-ton payload made it very valuable to the War Department.

The old-established London General Omnibus Company (LGOC) was among the most prominent operators during the reign of Edward VII, but it briefly fell behind when rival operators began running regular motor-bus services in 1905. The Vanguard fleet had constructed a four-acre factory site for motor-bus construction on Hookers Lane, in Walthamstow, which the LGOC acquired when it absorbed Vanguard in 1908. Naturally, LGOC proceeded to manufacture its own motor-bus designs, beginning with the X-type in 1909, followed by the famous B-type in 1910.

Even caked in mud, it is a very good-looking lorry.

Though the LGOC was beginning to establish a strong monopoly over London bus operations, it was seriously worried by an attempt by Daimler to build and run London buses itself and, by the start of 1912, it had consented to being taken over by the UERC to strengthen its foundations. This, in turn, troubled the Metropolitan Electric Tramways Company, which thus entered into talks with Daimler. It was in the midst of these boardroom battles that AEC was incorporated on 13th June, 1912.

Today, the Y-type has traded the churned-up Somme for a quieter life in Surrey.

Through careful manoeuvres, the UERC convinced the MET to agree to a pact of non-competition, quashing Daimler’s ambitions there and then. Daimler, of course, had equipped itself for bus production, and an agreement was reached whereby the Tramways (MET) Omnibus Company could purchase its chassis, but the LGOC would assume control of its operations in London. As storm clouds gathered over Europe, peace reigned at last over London’s transport network, with the LGOC agreeing that, for five years from 1912, it would employ Daimler and AEC as its only outside contractors, and each would have access to the other’s designs and patents for motor-bus chassis.

Its muddy make-up is left over from the film 1917.

Obviously, AEC’s first objective was to continue production of B-type chassis. By the time of its creation, the Walthamstow site had grown to almost 10 acres, making it the largest motor-bus producer in Britain and, in terms of output, at least as prominent as any other in Europe. AEC also supplied chassis to Daimler, in Coventry, which, in turn, fitted its own sleeve-valve engines and marketed them as Daimlers. The LGOC fleet reached its optimum size in 1913, causing Walthamstow to fall relatively quiet for a while, until war was declared in August 1914. Then, all of a sudden, there was urgent demand for as many lorries as could be supplied to the British military. As a matter of short-term expedience, a number of B-types were stripped of their bus bodies and sent to war having been rebuilt as cargo transport vehicles.

It shares its handsome radiator design with the earlier Daimlers.

To keep London ticking over, AEC was at first tasked with the replenishment of the LGOC fleet, while Daimler supplied the War Office with various three-ton lorries developed from the B-type chassis. The W-type had a strengthened front axle, heavier wheels and sometimes a four-speed spur gearbox in place of the three-speed chain ’box. The X-type had an improved rear axle and the Y-type, as well as all that, boasted a heavy-duty clutch and the four-speed as standard. Daimler built 2,799 Y-types between March 1915 and April 1917.

A simple canvas roof and doors afford minimal protection from the elements.

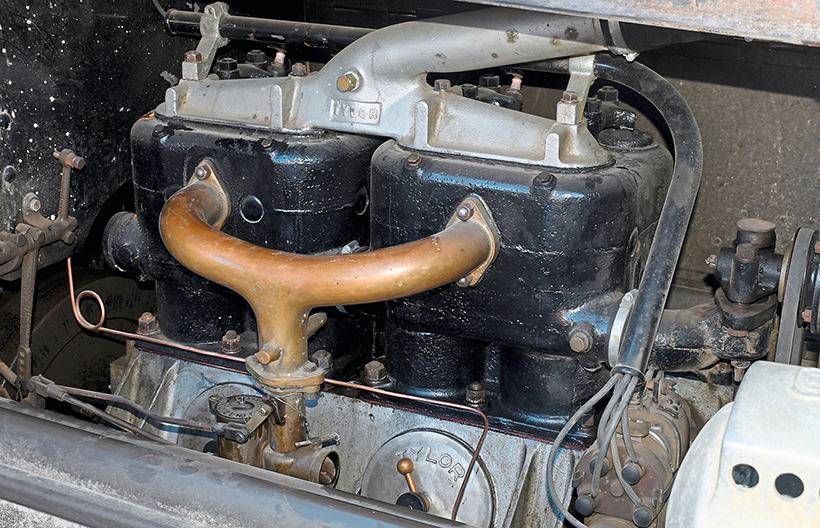

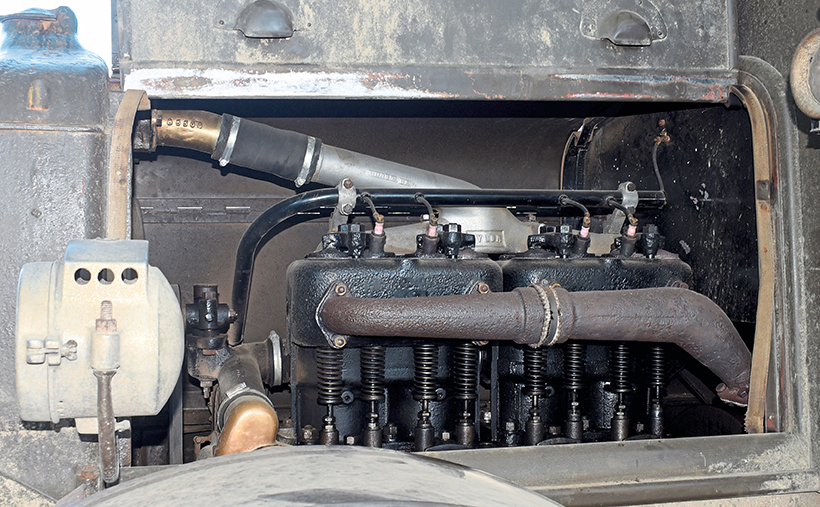

AEC had adapted the B-type for military use but, from January 1917, it also took up production of the heavier-duty Y-type. However, it no longer used its own engines, as it had in the B-type, nor the Daimler sleeve-valves, which were a little too delicate for military life. Instead, it approached a local firm, Tylors of King’s Cross, for the use of its JB4 engine; a T-head four with pair-cast cylinders amounting to 7,722cc in all. A Claudel Hobson carburettor and Thompson Bennett magneto were standard fitment. The radiator was similar to the Daimler’s, but with seven rows of 203 10mm tubes rather than 409 8mm tubes.

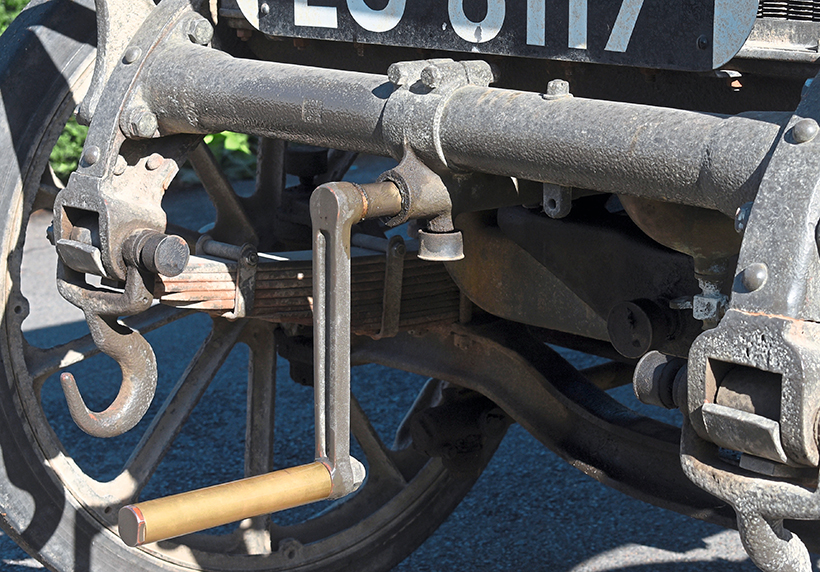

The sturdy front axle was inherited from Daimler.

The first YAs, like the Daimlers, had flitch chassis consisting of timber rails strengthened by steel plates. A pressed-steel chassis arrived with the YB, and the YC received a David Brown worm-gear final-drive in place of the Lanchester type. By the end of July 1919, 6,022 YBs and YCs had been built for the Ministry of Munitions. The post-war YD and YE were civilian models, with Lanchester final-drive but a higher gear ratio; the YE being more softly-sprung for charabanc use.

If necessary, the rear space could easily accommodate a few dozen troops.

We can imagine the rigours the Y-types faced on the Western Front, with all the gruelling work ferrying cargo and troops around – some never to return – but their peacetime existence was scarcely less hectic.

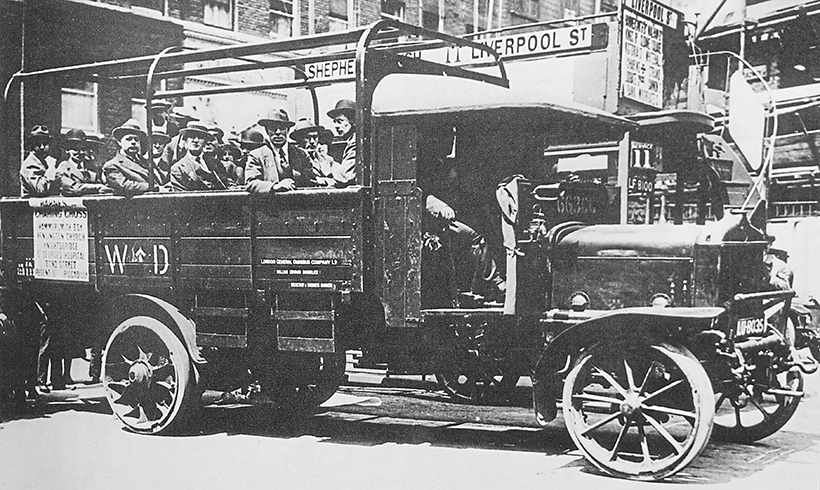

The military markings could be copied from period photos.

As the world returned to normal, public transport use increased dramatically through 1919 but, with so many buses having been given up for the war effort, and post-war material and labour shortages, the LGOC couldn’t cope with demand. The short-term answer was to fit ex-military Y-types with makeshift rear entrances and steps, plus benches along either side, and use them on London bus routes. In total, the LGOC adapted 180 lorries for the purpose, all on loan from the War Department. In November 1919, there were 176 lorry-buses in operation, but all had been withdrawn by the end of January 1920 as sufficient purpose-built buses had been recovered from France, repaired and returned to service. It was something of an ignoble destiny, as the public disliked them for their harsh springing and draughty bodies, and the LGOC operated them at a loss.

The AEC marque was only five years old when this Y-type was made.

AEC was naturally worried about its commercial prospects in a market flooded by war-surplus lorries so, in 1920, it bought back 171 of the LGOC’s lorry-buses and a further 78 surplus Y-types from the Disposals Board, which it rebuilt and sold on at a loss. This marked the beginning of what would be a very difficult period for AEC during the 1920s.

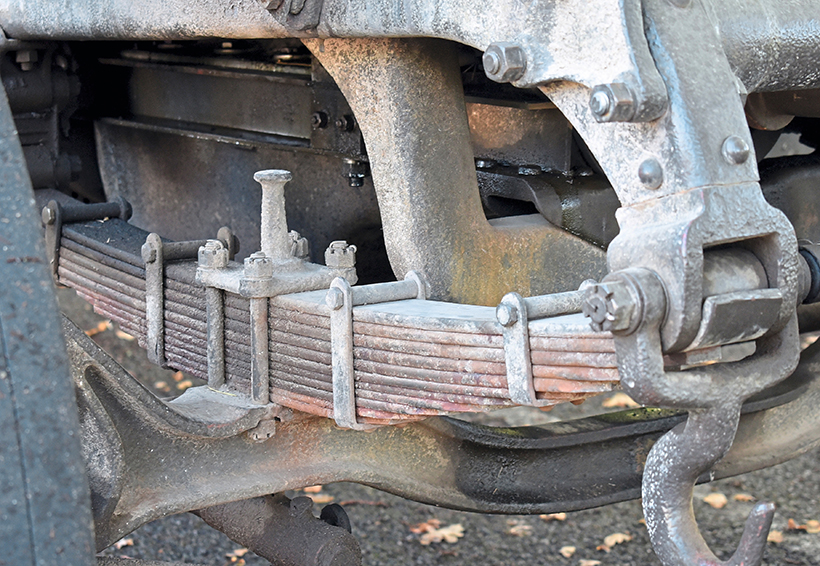

The stiff, robust springs contain no fewer than 11 leaves.

This 1917 YC survives today thanks to the efforts of Seb Marshall, whose name will be familiar to readers as the owner of Historic Vehicle Restorations, as well as the son of Old Motor founder, Prince Marshall. Some of its past is known, it having come to Seb from an enthusiast in Ireland who had acquired it from the Midlands, circa 1980.

The Tylor engine starts obediently on the handle.

From its chassis number and the few factory records that survive, he was able to determine that it definitely did go to war. Its purpose is not known for sure, but in all likelihood it would have been troop or cargo transport. On its return from the battlefields, it was among the 180 Y-types given the impromptu lorry-bus makeover by the LGOC, after which it went to the National Omnibus & Transport Co (formerly the National Steam Car Co), which was a rival to the LGOC until 1919, when it agreed to limit its operations to the provinces. With the National, it was fitted with a purpose-built omnibus body.

Spare cans of water, oil and petrol were vital considerations.

It came into Seb’s care in 2008, having been, by that point, completely dismantled. “We had to start from scratch,” he says. “We shot-blasted the chassis and built it back up from there. There was no body, but mechanically it was 98% complete. We put new bearings in the differential. The gearbox was in a very poor state, but we managed to get hold of another from Barry Wetherhead, and the engine needed a complete rebuild. We fitted liners in the block and new valves, guides and valve springs. It was all white-metalled. We had to find a magneto and a carburettor, and we made a new inlet manifold and water pump.”

Likewise, a shovel and pickaxe might have rescued this lorry on several occasions.

Relatively speaking, constructing the body was a straightforward task, but it had to be as correct and accurate as possible. A few other Y-types survive, which made the job easier. “There’s a really original Daimler Y-type with its original body,” he continues, “which is very similar to the later Ys. As we were doing this one, Graham Smith was restoring another YC, so we were all swapping ideas, taking photographs and scaling things. Graham had done some drawings, so we worked from there.”

The military Y-types had an 8.25:1 axle ratio.

The restoration was finished in 2015, although trouble with the water pump meant it missed that year’s HCVS London-to-Brighton. It made its début at the Great Dorset Steam Fair that year, and completed the Brighton Run in 2016. Since then, it has been shown and rallied extensively, going as far north as Beamish, and participated in a number of events to commemorate the centenary of the Great War. It also appeared in the 2019 film 1917, loosely based around the German army’s Operation Alberich, from which it still proudly sports its mud-spattered make-up, looking like it’s spent several months going back and forth across the sodden wasteland of the Western Front.

The driver’s cabin is naturally very Spartan.

Taking to the roads on a bright autumn day, the sunlight and bracing air make for a very leisurely drive, albeit not a conversational one, with the strong, slow-revving engine getting louder as speed increases until it drowns out everything else. The circumstances are so pleasant that it’s difficult to place oneself in the position of the drivers and passengers of 100 years ago, filled with dread and not knowing whether or not they might still be alive in a week’s time.

The central accelerator provides an extra challenge for modern-day drivers.

Seb says it’s an easy vehicle to drive. “The steering’s light and the gear-changes are easy for anyone who is familiar with a ‘crash’ gearbox. AEC Y-types really were at the pinnacle of World War I lorry design, but that’s because it’s an AEC and it was head and tails above everything else. It’s got a powerful engine and the brakes are very good. I can’t fault it really, it’s lovely. It’s not how people would imagine it to be. It was designed by people who built London’s buses and all of them were very light, easy, fantastic vehicles.”

The 7.7-litre Tylor JB4 is a strong, reliable and capable engine. Its only weakness in period was the lubrication system, which AEC later modified.

LU 8117 is more than just a rare survivor. It is also, for the time being, the oldest surviving AEC lorry in running order, but Seb is working hard to see that it does not remain so for long. He’s well into the restoration of the YA owned by Kevin and Alex Wheatcroft, of the Wheatcroft Collection, which has been known about since the 1970s but was only saved for preservation recently. It was one of the first built in January 1917, whereas the YC model was not made until the second half of the year. Seb says: “It’s been a harder project than the YC. We had to replace all the timber in the chassis because it had turned to peat.” It’s now recognisably a Y-type, though, and will hopefully be finished before too long.

The big exposed pushrods look decidedly robust.

With only a tiny handful of survivors from the original run of over 6,000, it’s as well we have someone like Seb who has had both the skills and inclination to save two of them, and not just because of their contribution to the British war effort; it was the Y-type which spurred AEC into the manufacture of large lorries for private clients and, as we know, it never looked back.

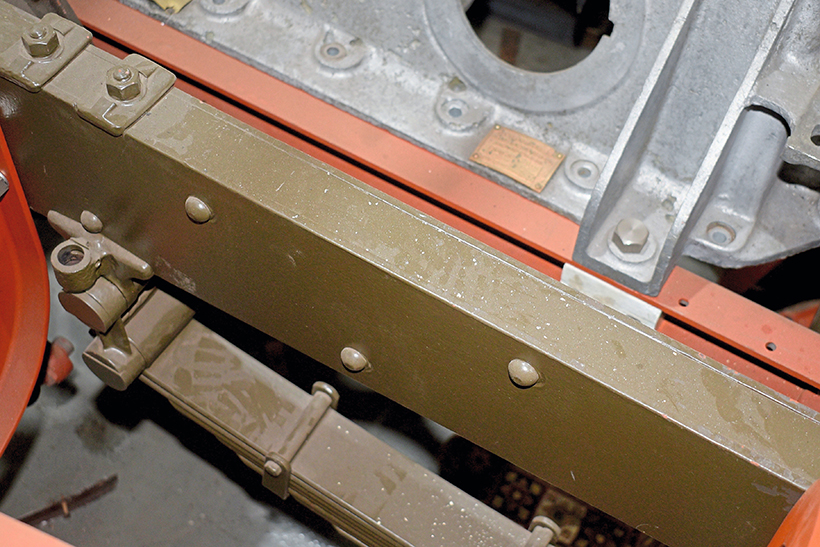

Detail of the Wheatcroft YA chassis, showing the flitch construction.

Showing just what an AEC Y-type can do, Seb Marshall drives with great gusto. (Pic: Peter Love)

Looking so authentic behind the French lines in WW1 goes the very rare AEC Y-type. (Pic: Peter Love)

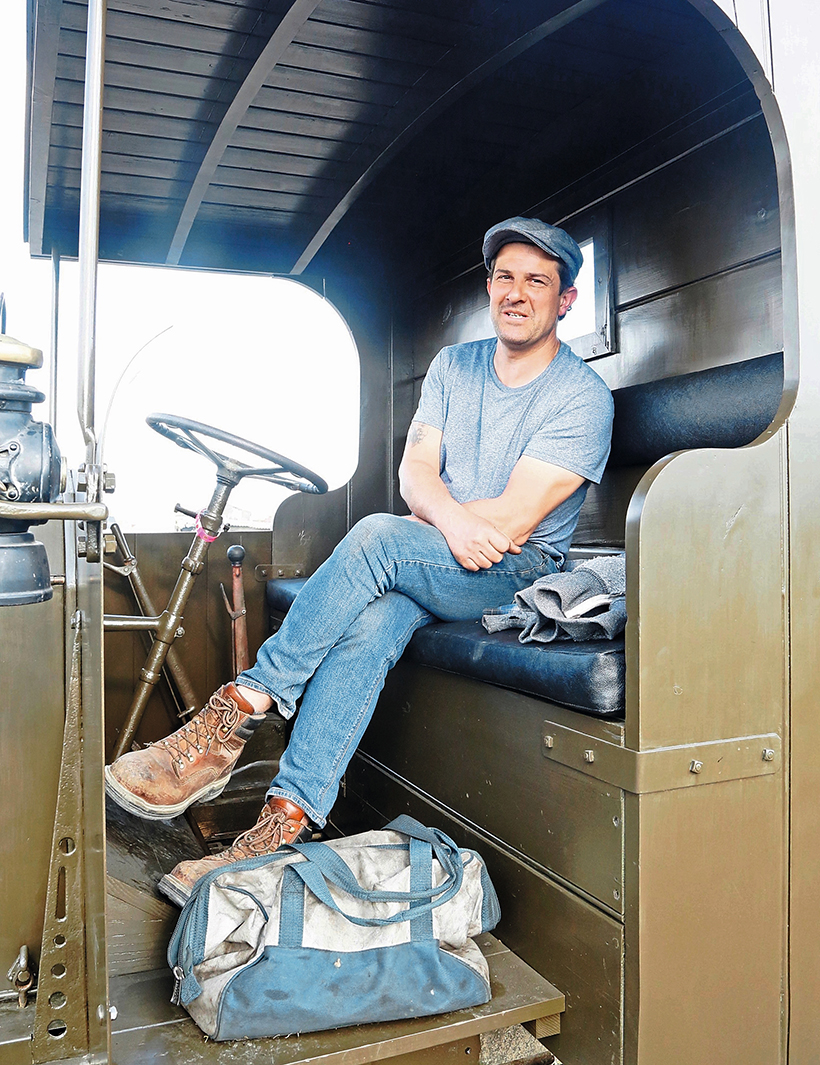

The man himself! Seb Marshall, who comes from a long line of pioneers in vehicle preservation. (Pic: Peter Love)

A newly-completed batch of YBs or YCs awaiting delivery at Chingford Mount.

A Y-type in post-war lorry-bus service.

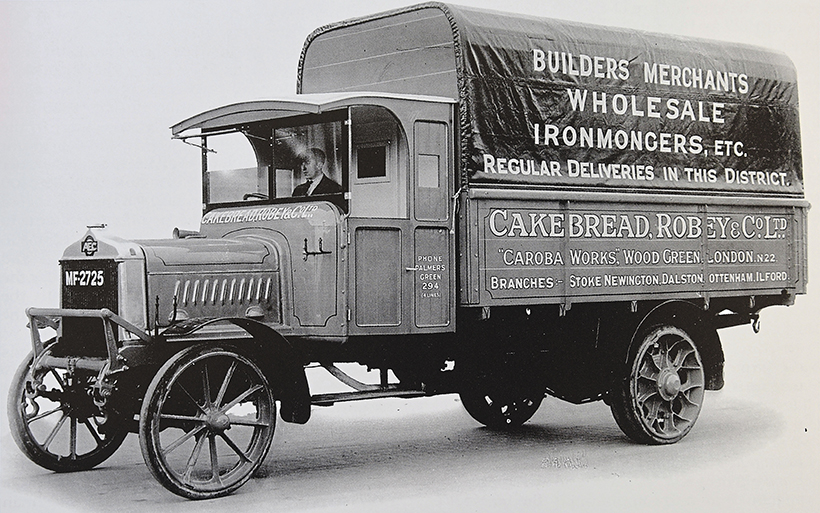

This delivery lorry featured AEC’s 5-type engine, which replaced the Tylor unit in 1921.

This Tyler-engined Y-type found a new life with the Great Western Railway.

A very attractive new cab has been fitted to this ex-WD lorry.

A rear view of a lorry-bus, showing the crude rear entrance and steps.

This feature comes from a recent issue of Old Glory, and you can get a money-saving subscription to this magazine simply by clicking HERE

Previous Post

Friends of King Alfred Buses running day confirmed

Next Post

Brilliant 16th Stotfold Mill Steam Weekend