A superbly-restored 1969 Massey Ferguson 135

Posted by Chris Graham on 25th July 2023

Willie Carson enjoys meeting Andy Catterson and recounts the story of his beautifully-restored, 1969 Massey Ferguson 135 tractor.

Andy Catterson’s beautifully-restored Massey Ferguson 135.

It’s impossible to imagine rural life without the Massey Ferguson 135. For livestock, arable or mixed farms, there was always plenty of work for Banner Lane’s most famous tractor of the 1960s and ‘70s.

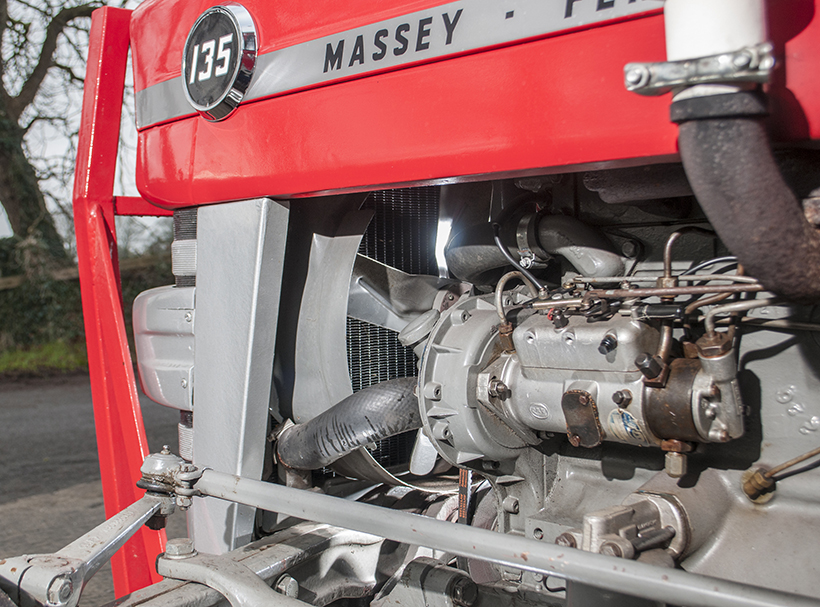

The MF 135 may have been the smallest Coventry-built ‘Red Giant’, but it was extremely versatile; a willing workhorse capable of much more than its compact dimensions might suggest. At its heart was the Perkins AD3.152, three-cylinder diesel engine, a descendant of the versatile P3 and P3.144 which had been used as an approved conversion, breathing new life into tired petrol and TVO versions of the TE-20 ‘grey’ Ferguson.

Since Massey Ferguson had acquired F Perkins of Peterborough in 1959, the AD3.152 had become the standard power unit for the 37hp MF 35 and, in 1962, its 44.5hp successor, the MF 35X. So, with a proven record for performance and reliability, it was the obvious choice to power the MF 135. But what made this such a well-respected engine? After all, the market competitors were offering their own compact tractors with similar power outputs.

Andy bought a Massey Ferguson MF41 plough, built in the same era as the Red Giants and a good match for the tractor’s capabilities.

Sound foundations

With a forged steel crankshaft running in four main bearings, the engine is based on sound foundations. The camshaft and injection pump are gear-driven, eliminating the problem of ‘timing scatter’, which blighted chain-driven engines as the chain stretched over time. Direct injection ensured that starting issues – even in cold conditions – were greatly reduced, and also allowed for an efficient combustion chamber design with a reduced surface-area-to-volume ratio, reducing heat loss to the surrounding metal surfaces and maintaining very good thermal efficiency.

The induction and exhaust systems were designed to flow through from the air filter on the right, towards the exhaust pipe on the left, creating a cross-flow effect. This allowed for a valve size and layout that was more conducive to effective charge flow, which is key to increased volumetric efficiency. It’s worth noting that crossflow cylinder head design wasn’t to be found under the bonnets of the top-selling motor cars of the era. The practical outcome of combining these design features is a reliable, fuel-efficient and powerful engine with impressive torque back-up.

Whatever the design brief given to the engineers in Peterborough might have been, few could have foreseen the character of this three-cylinder icon; something hard to define and impossible to ignore. Those that have spent time in the driver’s seat will know; it’s that eagerness for work, the willingness to rev, the induction roar and the exhaust pipe’s bark as the chromed throttle lever is pulled back. This is a very capable engine which punches well above its weight, making The MF 135 a true Red Giant.

Andy’s search for a 135 led him to Co. Donegal, where he found a 1969 model with 7,800 hours showing on the tractormeter.

New features

Behind the engine there were few features with which the operator of an MF 35 or even an FE 35 would not be familiar. The transmission took its drive from the engine via an 11in clutch, and provided six forward and two reverse gears. Power to the PTO shaft was available through the same clutch, or the more useful two-stage system with a nine-inch plate operating in the lower portion of the clutch pedal’s travel. Engagement of the PTO was by a dog arrangement aft of the hydraulic pump, which offered drive from the engine or the differential (known as ‘ground speed’). This delivered extra versatility and, as long as the clutch wasn’t fully depressed, a ‘live’ hydraulic system.

The Ferguson System remained a major part of the Red Giants’ specifications, and was developed from that which first appeared on the Model A ‘Ferguson Brown’. The new generation of the design featured draft, position and response control, and could also be specified with pressure control; an innovative feature that could be used to transfer weight from a four-wheeled trailer or trailed implement, to aid traction when grip was reduced in poor conditions.

To understand the principle of the concept, let’s take a quick look at the factors which affect traction, as they apply to a 2WD tractor. Tractive effort is a factor of tyre width, length of tyre contact patch, the ability of the soil to resist the shearing effect of the tyre treads and weight on the driving axle. In order to achieve good traction it makes sense to fit wider tyres; a simple fix unless you are working in row crops such as potatoes, where the wider tyre won’t fit between the drills or ridges.

The MF 135 does everything that Andy needs a tractor to do, and illustrates exactly why it was perfect for the small farm of the 1970s.

Getting a grip

The next thing to consider might be the fitting of tyres with greater diameter, giving a longer contact patch. Not a bad idea, but there’s expense involved. There’s not much you can do about the suitability of soil conditions on the day. Soil needs some moisture to make effective traction possible but, if it’s too wet it loses its structure and, instead of resisting the tyre treads allowing traction, it acts as a lubricant – the tyre spins and, before you know it, you’re in mud up to the gunwhales, and walking over to the neighbour’s to ask for a tow. But what about the part of the equation which we haven’t yet discussed, weight on the driving wheels?

Look through the list of equipment options from tractor manufacturers of the day and you’ll find wheel weights and wheels with cast centres, both available as traction aids. It was also common practice to fill tyres with water ballast for the same effect. The downside of these solutions is that all the extra weight has to be lugged around all the time, but may only be needed for short periods of the day. Of course, when you need the extra grip you really need it, and this is exactly where Massey Ferguson’s pressure control system scores.

To make use of this feature, the operator first fitted a pressure control coupling to the lower links of the tractor, then looped a chain from the coupling, below the implement drawbar and back up to a fixing on the coupling. When the quadrant lever is adjusted, the lower arms react, putting strain on the chain and effectively transferring weight from the wheels of the trailed implement and the front wheels of the tractor and adding it to the driving wheels. And all at the touch of a lever by which the oil pressure in the system can be varied from 150 to 2,550psi. Wheel spin is reduced, work rate increases, the dozing effect of the front wheels is reduced adding to fuel saving; add to this the differential lock, fitted as standard equipment, and its win-win!

Andy wanted a more modern cab than the old Duncan one his tractor came with, so opted for a Super Duncan, with its closed-in rear section.

Effective performance

The system was particularly effective when pulling a four-wheeled trailer or trailed discs, and was the salesman’s trump card when the tractor was to be used in conjunction with the popular MF 711 trailed potato harvester, the axle of which was positioned near the machine’s centre, offering little drawbar weight to aid traction. The Ferguson System might have already been on the market for a generation, but its up-to-date improvements wrapped up in stylish body panels with a modern dash comprised of five gauges and most memorable central dash lamp, meant the success of the 100 Series middle weight was assured.

Andy Catterson had his mind set on owning a Massey Ferguson 135, but it took a while before his ambition was fulfilled. “The first tractor I drove was my grandfather’s MF 35X,” says Andy, explaining his passion for the brand. “He farmed about 80 acres of hill land where he kept 20 Aberdeen Angus or Hereford cross suckler cows. He sold the calves at the autumn sales, but he also grew spuds and barley and made his own hay. The 35X was his only tractor so it did a fair bit of work in its time, and I was as keen as any other young lad to be in the driver’s seat.”

In 2012, Andy’s search for a 135 led him to Co. Donegal, where he found a 1969 model with 7,800 hours showing on the tractormeter. “I wrote to the original owner’s address on the old tax book not really expecting a reply, but they wrote back to tell me that it was bought new in June 1969 by the Harrold family of Kilmeady, in Co. Limerick. They bought the tractor from Geary’s Garage for £810IR along with a haybob at £135IR, a buckrake at £25IR and a transport box at £32IR. It stayed on the Harrold family farm until 1982 when it was sold to Michael Donnegan, a dealer who then sold it to Mr Noonan, also of Co. Limerick.

He fitted carpet sound-deadening to the inside of the cab roof and to the mudguards, bolted in a new seat and fitted new rubber floor mats, to make the tractor quieter and more comfortable.

A risk worth taking

I don’t know when it made the journey up to Donegal but, when I found it, it was fitted with an early Duncan cab, the engine was turning but it wasn’t running. I thought that the problem was related to the fuel system, so I took a chance that it could be fixed and bought it. The first job was to take the injection pump off and the injectors out and leave them with Erne Diesel Services where everything was reconditioned. When it was all back together and the pump was bled, the engine fired-up easily enough and I used the tractor for a couple of years, carting turf and sticks. All was going well until the oil pump failed and the engine seized one day, on the way home from the bog.

“I stripped the tinwork and the fuel tank, removed the front axle, craned the engine off the gearbox and took it to Mervyn Elvin, in Letterkenny, where it was rebuilt. It needed pistons, rings and liners. The crankshaft was reground and refitted with new shell bearings, and a new oil pump was fitted, too. There were new camshaft bearings installed together with new cam followers, the head was reconditioned and Mervyn fitted a new water pump, a new radiator and then a new clutch kit.

“I hadn’t intended to do any more than refurbish the engine but, while it was away at Mervyn’s, I took a look at the front axle. The pivot pin came out easily enough, so all I had to do was to fit new bushings, but the kingpins were more of a problem. I had trouble driving out the old bearings because they were so worn but, once they were out, I was able to rebuild them using the old stub axles and a complete set of new bearings.”

The engine was turning but wasn’t a runner when Andy bought the tractor. But he thought the problem was fuel system-related and that he could fix it, so he was happy to take a chance.

“Why stop now?” Andy asked himself when he realised how much he’d already achieved. “The gearbox needed new input shaft bearings and seals while the clutch shaft needed new bushes fitted to the casting. I had to replace the gear lever because the ball was worn so it would stick in gear, stick between gears or maybe even select two gears at once. The hydraulics were tested and showed good pressure, and all the parts where I expected to find problems were grand.”

Further repairs

“The bearings in the cross shaft were good, the levelling box was working properly and the lower link pins in the trumpet housings weren’t overly worn. I had to replace the balls in the arms, but that was all the hydraulic system needed. The PTO seals and half shaft bearings and seals needed to be replaced, and the brake shoes had to be relined because the oil leaks had contaminated the original linings, although the rest of the brake system was fine. I had to rebuild the steering box with a new steering shaft, ball race and seals.

“The radius arms weren’t too badly worn, but I did find a flattened tuppence coin already in the ball joint, acting as a packer. The old rims were very badly pitted so I bought new replacements and fitted 16×6.00 tyres on the fronts and 360-70 R 28 Agrimax tyres on the rears. They give a bigger footprint which is ideal for going to the bog for turf.”

The reproduction loom had to be extended to provide connections for the cab and to supply the ploughing lamp. New Wipac lights were bought for the rear.

Andy wanted a more modern cab than the old Duncan model, so the Super Duncan with its closed-in rear section and subsequent lower noise levels seemed the obvious choice. “I took off the old Duncan and sold it to help pay for the new cab. I found one which had been fitted to an MF 230 which had been completely burnt and written-off. The cab wasn’t any more than a frame and two doors, so the first thing I did was to send it to the shot-blaster so I could identify how much of it was sound metal.

It wasn’t too bad under the rust, so I filled the box sections with Waxoyl to stop it rusting from the inside. I gave it four coats of hi-build primer, then seven coats of MF red finish. Alan Donnell came and measured for the windows, cut the laminated glass and then fitted them with new rubber seals. The gas struts are just off-the-shelf parts, and the new roof panel was folded by a local engineer.

Quieter cab

I fitted carpet sound-deadening to the inside of the roof and to the mudguards, and bolted in a new seat and fitted new rubber floor mats. I was able to buy a reproduction loom for the tractor, but had to make my own sub-loom for the cab, including a supply to the ploughing lamp. The headlights are the original Butler units, but I had to buy a set of Wipac lights for the rear.

Andy believes that tractors should work as they were designed to do, so he really enjoys ploughing with his 135.

“From start to finish it took two years to build, working two nights a week and at weekends. I go to local shows and road runs, and use the tractor to split sticks for the fire, but a tractor should be working like it was designed to do, so I like to do a bit of ploughing if I can,” Andy explained.

He bought a Massey Ferguson MF41 plough, built in the same era as the Red Giants and a good match for the tractor’s capabilities. With settings for 10, 12 and 14in furrows, a strong diamond-forged steel beam and category I linkage pins it appeared on the 1970 listings, priced at £120 10s with rigid bodies. The spring release version cost an extra £31.

Andy is often seen at working days with his MF 135, ploughing or cultivating with his recently-acquired set of discs and showing just what a versatile tractor the iconic MF 135 really is. It does everything that Andy needs a tractor to do, and illustrates exactly why it was perfect for the small farm of the 1970s.

The replacement cab Andy sourced wasn’t any more than a frame and two doors when he bought it. It was shot-blasted and Waxoyled, then treated to four coats of primer and seven coats of MF red paint before being glazed.

We’d like to thank Will Cather for kindly granting us permission to use his farmyard as a photographic location.

This feature comes from the latest issue of Classic Massey & Ferguson Enthusiast, and you can get a money-saving subscription to this magazine simply by clicking HERE

Previous Post

1984 Bedford TL that’s been stunningly restored

Next Post

Ford Thames Trader models for collectors