BMC’s half-tonner

Posted by Chris Graham on 16th April 2021

Peter Simpson profiles BMC’s half-tonner, the bigger, car-derived light commercial vehicle from the 1960s, and ponders a missed opportunity.

BMC’s half-tonner: A fine-looking, 1968 Austin pick-up photographed on the 2018 HCVS Ridgeway Run. Big load-bed, a decent-sized cab and a tougher-than-average construction made these a farmer’s favourite. (Pic: Terry Blackman)

On the face of it, BMC’s half-tonner, light van range in the 1960s was far more comprehensive than that of any of its rivals. Ford and GM offered, basically, one car-derived van (Bedford HA and Ford Anglia/Escort) and one Transit-sized vehicle (Bedford CA, Ford 400E/Transit).

BMC’s range, by contrast, comprised five vehicles. First up was the quarter-ton (5cwt) Mini van. Then there was the Morris Minor-derived 6/8cwt and, until 1968, the 5cwt Austin A35 van. This was followed by the Austin/Morris half-ton/10cwt car-derived van based on the pre-Farina Austin Cambridge, after which came the neat-looking 10-12cwt J4. Finally, weighing in at 16-18cwt, there was the J2, replaced in 1967 by the relatively short-lived and now-rare JU250.

A van version, showing the class-leading big body to good effect.

Crossover and duplication

However, despite being comprehensive, this range contained a fair amount of crossover and duplication. Some was understandable. For example, fleet buyers– with good reason, it has to be said – were wary of FWD so, while the Mini van’s transverse engine and low, uninterrupted floor made it almost-ideal as a small van, BMC still had to offer RWD alternatives in the form of the Minor van for Morris dealers and, for the still part-separate Austin network, continue with the A35 until 1968, then replace that with an Austin-badged version of the Minor van.

In other places, however, the closeness/crossover is difficult to understand. Take, for example, the third car-derived van in the BMC line-up, the Austin/Morris half-ton van and pick-up. Introduced in late 1956, it had exactly the same weight payload as the smallest J4, introduced four years later, although the latter was, space-wise, significantly bigger. Yet the car-derived half-tonner remained in production for 16 years and, apart from receiving a slight facelift and the addition of a Morris-badged version from 1962, changed little.

A wonderfully-conserved and original, pre-facelift pick-up, seen at The Great Dorset Steam Fair a couple of years ago. All versions could be ordered in factory primer rather than top coat, ready for the owner’s own livery to be applied.

Part of its attraction was clearly that its 110cu.ft space, though smaller than the J4’s 160cu.ft was, along with that 10cwt payload, significantly bigger than any other car-derived van at the time. By comparison, Ford’s Anglia or Escort maxed out at 8cwt, and could take just 82cu.ft. Similar comparisons applied to the Bedford HA and Commer Cob. BMC clearly saw a market for a big, but still car-derived, LCV.

Straight successor

Yet, despite its unique position in the market, the BMC half-tonner was a straight successor to two previous models, albeit replacing the second one six years after the first. It was introduced, in Austin-only form, in November 1956, to replace the previous A40 Devon-based 10cwt/half-ton van, which dated back to 1948; the Devon saloon having been replaced by the A40 Somerset in 1952.

Sun-tor camper conversions were popular, and are now highly-prized, though they’re definitely two-sleepers rather than for family-use.

The new van was based on what’s now known as the ‘pre-Farina’ Austin Cambridge, of all-steel unitary construction, and shared the car’s front-end styling along with its column-gearchange and 1,489cc BMC B Series engine. Though of the same 10cwt/half ton payload weight as its predecessor, that 110cu.ft capacity was a significant and useful step forward.

In May 1957, a 40cu.ft pick-up truck version was added, with a bench-type front seat as standard. At the same time, and presumably connected with the pick-up requiring a more separate chassis, the options of purchasing a chassis/cab unit or a chassis/scuttle with nothing bodywise past the windscreen, were offered for those wanting to add specialist bodywork.

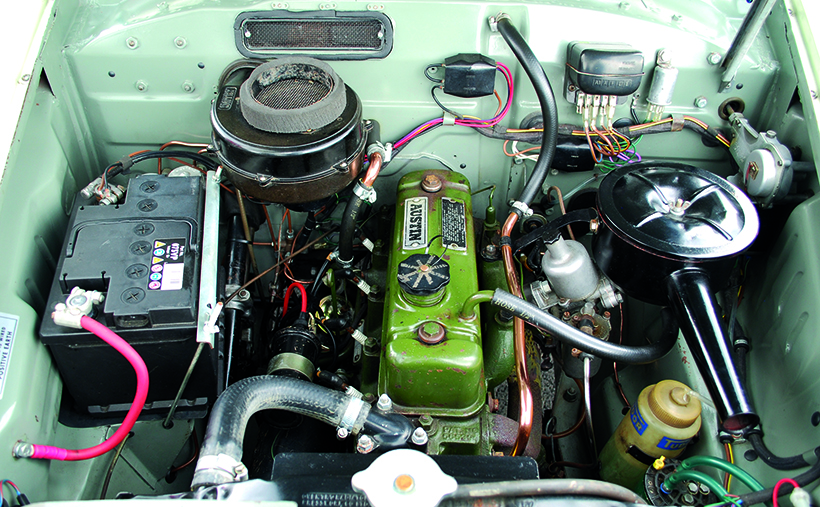

Distributor servicing and (especially) oil filter changes are notoriously tricky – it’s often easier to take the dizzy out to change the points. (Pic: Mike Neale)

The vans were allocated chassis code ‘HV6’, the pick-ups ‘HK6’, the chassis-cab option ‘HQ’ and the chassis-scuttle ‘HR’ and, although the chassis numbering system was revised in June 1959, when five-digit numbers beginning at ‘22800’ replaced a six-digit series which finished at ‘178300’, the codes with which chassis numbers started, remained the same throughout the production run.

The half-ton commercials were made at Longbridge, and those who, like me, grew up in the 1960s may recall, Ladybird’s Easy Reading book The Car Makers. This includes a wonderful illustration, in classic Ladybird drawn-from-life style, of the A60 Cambridge production line, with a half-ton van going down the track in between cars. Production records are held at the British Motor Museum, Gaydon.

In October 1962, the range was revised for the first and only time. The most noticeable change was at the front, where a narrow but full-width grille arrangement replaced the previous, curved-side arrangement, and a stronger front bumper was fitted together with chrome body-side mouldings. Also, 14in wheels replaced the previous 15in items, non-reflective paint was used on the dash and, most important of all, a glovebox lid was fitted.

This is actually an ambulance conversion with non-original seats; pick-ups came with a bench as standard but, on vans, the front passenger seat was an extra-cost optional extra. (Pic: Mike Neale)

At the same time, Morris-badged versions became available, replacing the previous 10cwt Morris vans, which had been based on the pre-Farina Oxford. Apart from having a Morris-type radiator grille, and Morris badges on the bonnet and steering wheel, these were identical to the Austins, and they shared the same chassis number series.

One year later – from September 1963 – the half-ton van range received the 1,622cc version of the BMC B Series engine, which had been used in the A60 car range since late 1961.

And that was it – nothing else changed until production finished in October 1972. Except that in 1970/71 – the precise point isn’t known – a combined steering column lock/ignition switch replaced the previous dash-mounted key-switch. This change, which also applied to Minor vans, was made only because changed Construction & Use rules made a key-operated immobiliser compulsory.

The main markets for these vans and pick-ups seems to be one-off purchases by the self-employed, and for use by shopkeepers and other small businesses who wanted a bigger, car-derived van, even if many aspects of it were decidedly old-fashioned. The building and construction trade also liked the bigger internal space and the relatively heavyweight construction. Some were also used as the basis for special bodywork as newspaper delivery vans and, of course, Tor Cars of Devon designed and sold an extremely successful, two-berth Sun Tor camper version.

Austin and Morris steering wheel badges came from the contemporary Cambridge and Oxford cars.

Farmer’s pick-up

There was, though, one group whose widespread use of both the van and pick-up version is probably responsible for many of today’s survivors still being around. I’m talking about farmers. In agriculture, a big car-derived van or pick-up that could swallow anything from milk churns to animal feed, fertilizer, hay bales or even the occasional sheep or goat, was ideal. The pick-up, too, could almost have been designed for agricultural use. Besides having a bigger load-bed than most rivals it could, thanks to its bench seat and column gearchange, take farmer, wife and working dog (or even three adults) to market in, if not total comfort, then certainly far from total discomfort.

Farm vehicles work hard, and not all receive massive amounts of tender loving care. However, they often tend to fade gradually out of use, rather than being stopping suddenly. Typically, an MoT failure might be put to use as an around-the-farm hack and, as the years rolled by, it would spend less time out and about, and more standing idle. Eventually, it would get laid-up and then, many years later, a sympathetic enthusiast would come to its rescue.

Sought-after classics

Like most classic light commercials, BMC half-ton values have increased significantly in recent years, and decent ones are now well into five figures – in fact, they’re almost in line with Morris Minor vans. The pick-ups are especially sought-after as, to some, that combination of pick-up truck and ‘four on the tree’ has a rockabilly truck appeal.

Values of all – but pick-ups especially – have risen significantly in recent years, making proper restoration much more viable.

So, what should you look for if considering buying? Rust, obviously, is the major issue. As you’d expect, the back-end of pick-ups is especially prone, both underneath and on-top, and replacement panels simply aren’t available. Look out, too, for rot in the roof guttering. The mechanical side is generally straightforward, and parts can usually be found with a bit of ‘knowledge’. Slightly ‘floppy’ front suspension – due to worn kingpins and (especially) lever-arm shock absorbers – is common, but relatively easily sorted.

Missed opportunity?

The half-ton van, and the 6-8cwt Minor, were replaced by one model – the Marina-based van, which arrived in August 1972, with a choice of seven or 10cwt payload. At 88.5cu.ft, the Marina was bigger than the Minor van, but significantly smaller than the half-tonner. Half-ton sales had, perhaps unsurprisingly, collapsed by 1971; chassis numbers suggest total sales of around 7,000 in the final full year, compared to around 67,000 in 1962 to 13,000 in 1968.

Hindsight is a wonderful thing. I can’t, though, help wondering whether BMC missed an easy trick here which would, at minimal cost, have given them a unique product in the light van market. Why, oh why, didn’t it offer the half-tonner as a 1.5-litre diesel? The engine was there, and had been well-proven in the J2 and J4 vans. It was also being used in the Austin Cambridge and Morris Oxford cars, meaning any installation redesign work needed had already been done.

Some, however, prefer to conserve them with a working-van appearance – in other words, as most of us will remember them!

It would have been slow of course – probably 45mph at best – but still probably faster than a diesel J2 or J4. But surely, in this marketplace, 40mpg economy would have mattered much, much more, and could have been a huge unique selling point.

What’s more, with both the Ford and GM car-derived rivals being based on 1.0-litre engines with no direct diesel alternative, neither could have countered it easily.

It wouldn’t have been a 100%-guaranteed win, of course; for example, the extra cost of a diesel might have put some buyers off. But, given that everything needed was to hand and, basically, ready, it could have been tried easily and at virtually nil-cost. And it really does beggar belief that it never was…

For a money-saving subscription to Classic & Vintage Commercials magazine, simply click here