Those who preserve our cherished vehicles deserve praise

Posted by Chris Graham on 11th April 2024

Zack Stiling reflects on the essential enthusiasm and dedication of those who work so hard to save and preserve our cherished vehicles.

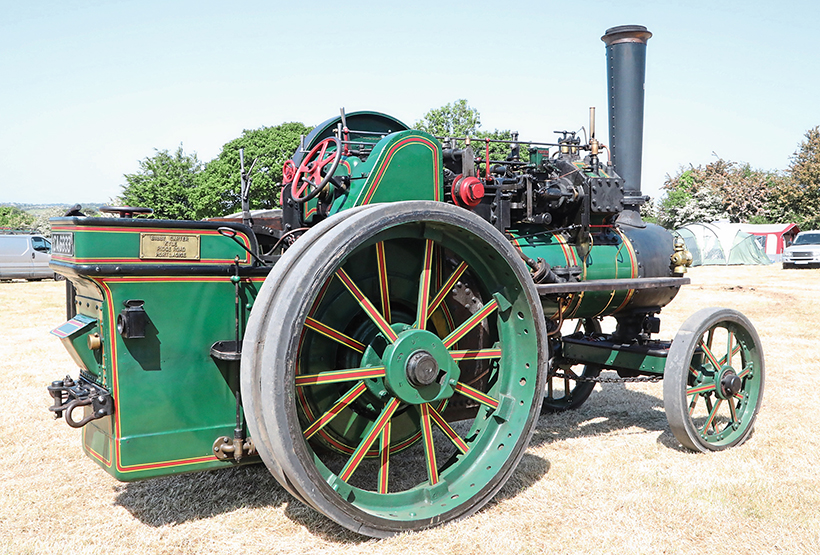

Cherished vehicles: It’s difficult to restore a steam engine back to good health and keep that working look, but Dauntless shows it here admirably.

“Without the past, there is no future,” and phrases to the same effect, have been circulating in political and intellectual discourse for decades. It should also be stated that without preservation, there is no past. History itself, as opposed to pre-history, begins c3200 BC with the preservation of knowledge, made possible by the invention of writing on clay tablets by the ancient Sumerians. With that, knowledge of other early technologies could be shared and the seeds of the first civilisations sown. These tablets themselves were preserved, being placed in archives in sacred temples and royal palaces, with the result that thousands have survived to the present, gifting to modern man an immensely detailed understanding of what life was like during the nascence of civilisation.

Some people like the rusty/primer look, others not. What do you think?

That alone ought to make clear the importance of preservation, and to say as much in Old Glory is, one imagines, preaching to the converted. Readers who have laboured for hours to revive a steam roller and living van, or a steam-driven threshing machine, may have done so chiefly because they enjoyed it, but they will not have been unconscious of the fact that if this old machinery was allowed to decay or be broken up, it would leave a gaping hole in the pool of human knowledge and future generations would be poorer for it.

Tony Donavan is a strong believer in keeping tractors in original condition just as they last ran in their working lives, but does the general public get the authentic look?

In many ways, traction engines and old commercials have proved a surprisingly enduring link with our past, more so even than our townscapes and the very land beneath our feet. Who spares a thought for the farmers and ploughboys who once toiled on land now occupied by Barratt homes and financed BMWs? When we see a 12-pump petrol station sitting canker-like on the outskirts of a village, who remembers that it was built on a site formerly occupied by a family-run garage and cycle works, and for a century before that by the village forge, so vital to life in the community? All might be lost from sight completely, except that there still exist old lorries bearing the names of ‘Scroggs’ Garage’ or ‘Johnson’s Agricultural Sundries’, providing a tangible link to a vanishing way of life.

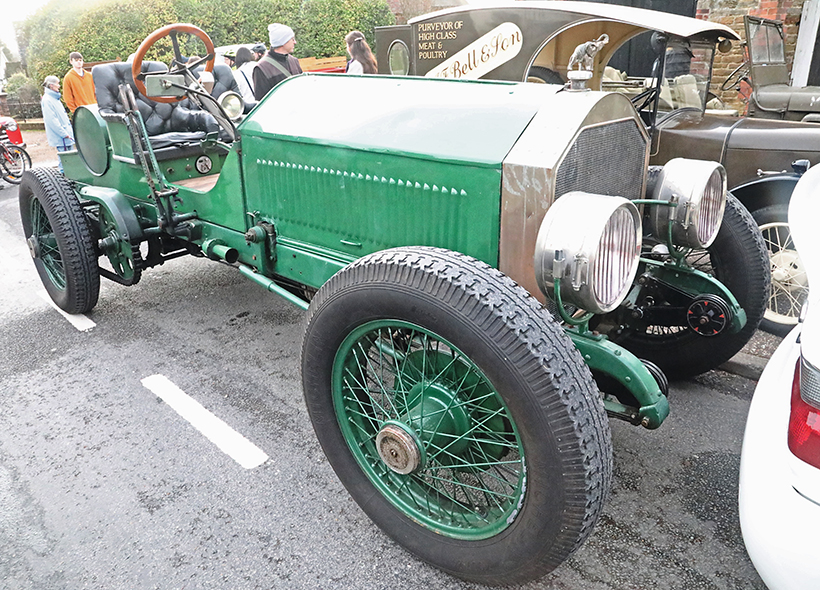

1914 Peerless Model 48 speedster with a sign telling visitors that it was newly restored. In fact, it had been imported into Britain following an American auction in 2019.

One likes to think that this philosophy is generally well-heeded, but it is lamentably the case that in parts of the historic transport movement, particularly the vintage car world, there exists a philistine faction which has purely selfish motivations and no respect for history or originality. It is difficult to imagine this exists to the same degree in steam and commercial-vehicle preservation, which have never had their objectives derailed by a desire to win races or look glamorous, but certainly one feels for the American fire engine enthusiasts who have torn their hair out trying to prevent the transformation of American LaFrance vehicles into some ridiculous approximation of an Edwardian speedster which resembles nothing that existed in period. Doubtless, too, many original Model T Ford and Austin Seven vans have been sacrificed at the altar of special-building. It is true also that many replica showman’s engines have been made from machines which only existed in period as steam tractors or mostly road rollers, but sitting as I do on the periphery of the steam scene, I am in no position to pass judgment on them.

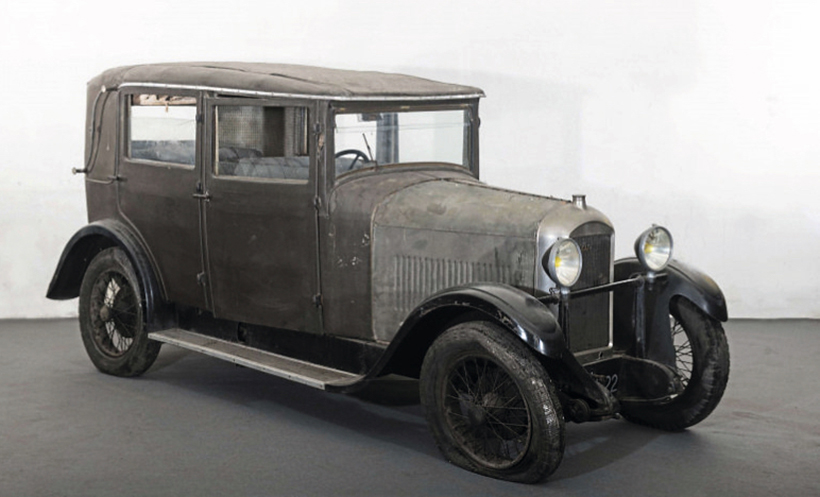

This is what the 1914 Peerless looked like when offered at auction in 2019. A unrestored and supremely presentable town car bodied by the high-end Chicago firm of Kimball.

Since the early years of the vintage car movement, when the cars themselves were more common and less historic, there has been no shortage of ‘body snatchers’ – those who think nothing of throwing away original bodywork to replace it with something invariably inferior contrived for the sake of going racing or grossly misguided aesthetic reasons. There are also unscrupulous businesses which hope to profit by it. Nowhere is the practice more notorious than in the vintage Bentley world, where dozens of beautiful original saloons, landaulets, all-weather bodies and so forth have been callously discarded to aid the creation of identical, make-believe Le Mans replicas. In more recent years, there has been an encouraging reaction against this practice, but still it goes on.

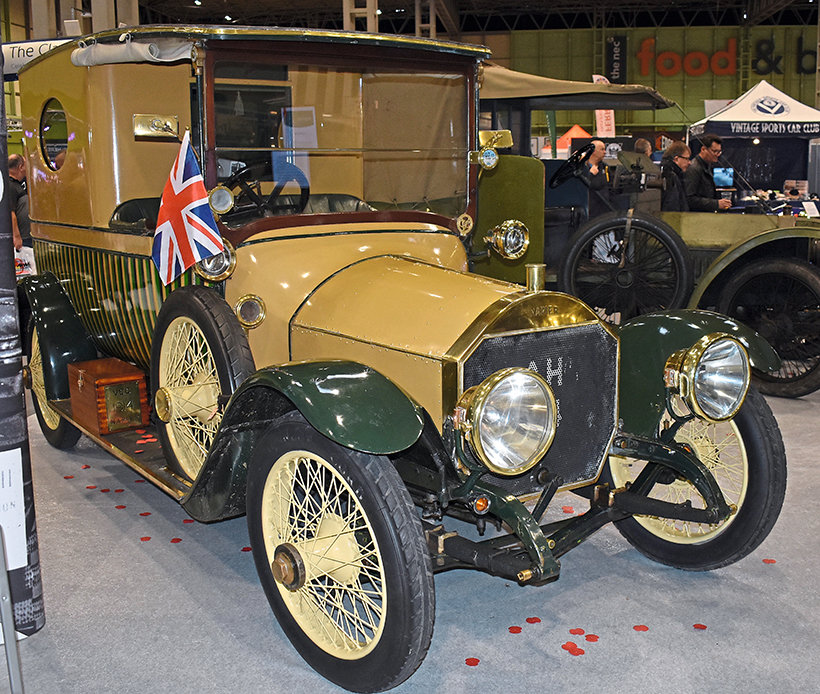

The WW1 period Napier and the Crossley ooze authenticity in different ways.

In June, 2023, a 1931 Bentley 4-litre with its original drophead coupé bodywork by Freestone & Webb sold at auction. Within two months, the body alone was being advertised for sale by a Berkshire-based vintage Bentley specialist. Chassis No. VA4100 was not merely a very original and correct example of a rare and overlooked Bentley, there having been only 50 4-litres ever built; it was nothing less significant than the last Bentley made at the Cricklewood works. The chassis and body may both still exist, but unless the two are reunited, it has to be understood that the last Bentley built during the ‘WO’ era has ceased to exist on someone’s whim.

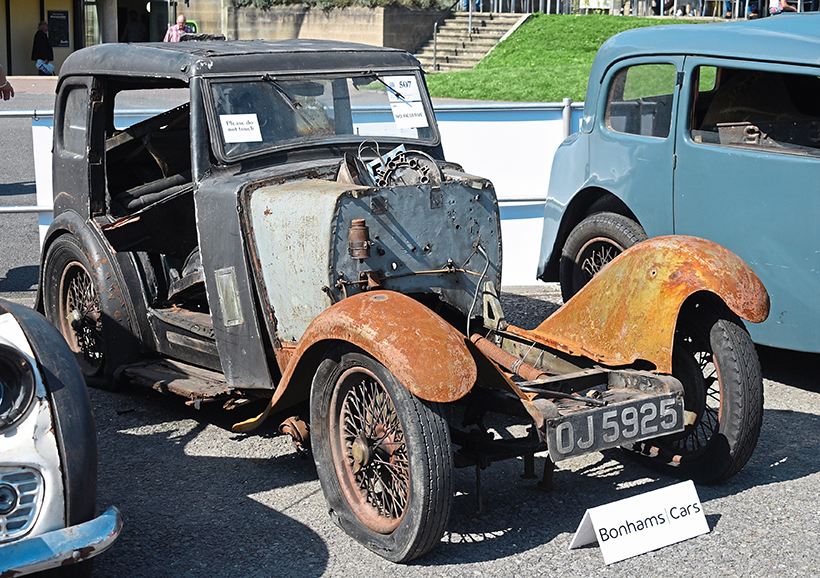

The seats could have been repaired in keeping with the car.

Sadly, 2023 has been a bad year for it. This article was prompted by the fact that, at the NEC in November, there was exhibited by the FBHVC a 1914 Peerless Model 48 speedster with a sign telling visitors that it was newly restored. In fact, it had been imported into Britain following an American auction in 2019, where it appeared as an all-original, unrestored and supremely presentable town car bodied by the high-end Chicago firm of Kimball. At the Beaulieu Autojumble auction, the sole-surviving, dilapidated but restorable, 1933 Wolseley Hornet Special with salonette bodywork by Patrick Motors sold to a well-known family of special builders.

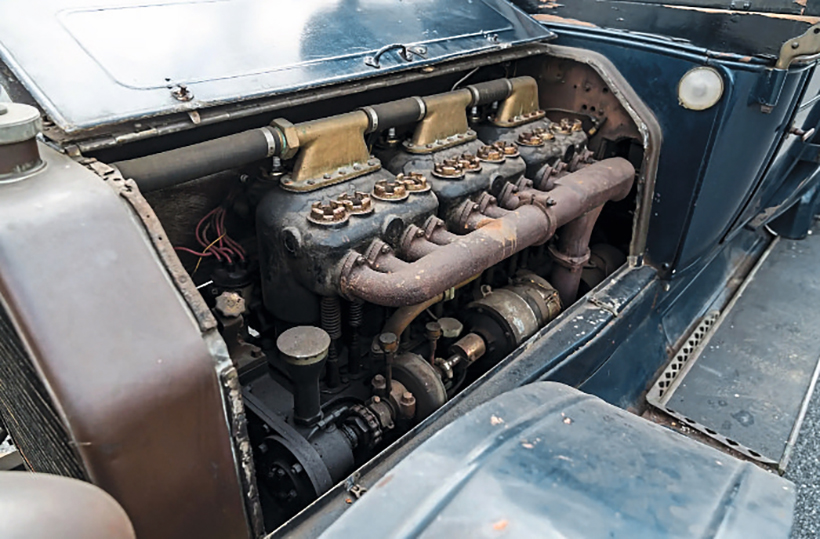

The engine compartment on the Peerless is something else.

The outcome was as feared, although following an outcry it has been promised that the original body will be restored on a different chassis. This is a positive outcome under the circumstances, but the separation of a body from its original chassis to be rebuilt on another one is infuriating in its pointlessness.

It is fortunate that in all of the above cases, the bodywork of each car has not been destroyed. The same could not be said for the 1929 Amilcar Type M Weymann saloon which was sold from a French collection in 2018 as a totally original, unrestored car. An enthusiast bought it, sympathetically recommissioned it and presented it on a preservation-themed rally, where it drew praise from the old-car press. Months later, it was offered for sale by a European dealer as a bare chassis, advertised as being ideal for a CGSs replica. If the body still exists, its whereabouts are not known. Still, a Dutch dealer is advertising on PreWarCar.com an extremely rare 1932 Invicta 12/45 saloon by Carbodies, which needs restoration but is eminently restorable. He describes it as ‘suitable for making a special.’

If the owner had gone down the popular route of re-bodying it as a tourer, we would be left with a mere simulation of a 1920s car. We are fortunate, instead, that we are still able to see and experience the Ghost as it was during the second phase of its working life.

It does not take much imagination to appreciate what the long-term impact of this thoughtless vandalism is, how the enthusiasts and historians of the future will suffer for not being able to see, touch and drive genuinely historic cars because they have been turned into fakes and fantasies, but it is nevertheless worth citing an historic example.

I recently met a great Lagonda enthusiast whose interest was sparked by his father, who arrived home one day in the 1950s waving his arms, grinning from ear to ear and generally reduced to a state of childlike ecstasy. He had just bought a Lagonda V12 saloon, but what animated him so was the name in the logbook: WO Bentley. Bentley was, by the late 1930s, working for Lagonda and oversaw the development of the V12. The father promised the car to the son, but unfortunate circumstances meant it was sold out of the family.

By retaining its post-war camera car body, the man who put this Silver Ghost back on the road has saved a unique piece of history.

The son vowed to track it down and buy it back, but when he caught up with it, it had been destroyed. That is to say, the body and interior had been binned and it had been rebuilt as a Le Mans fake. That, of course, was a great personal loss for the owner as it had severed a tangible connection with his father, but in a broader sense it is everyone’s loss. Never again will anyone enjoy the view down the bonnet which Bentley enjoyed, or feel the leather on which he sat, or admire the coachwork which he admired. All was lost so one man could pose as a racing driver.

Electric conversions pose a different potential threat which was barely imaginable 15 years ago. Naturally, several Austin Sevens and Model A Fords have already suffered this indignity, but proponents of the fad maintain that responsible conversions are reversible. However, not all vintage cars are Sevens or Model As.

Keeping vehicles authentic to its working life is very difficult and those that do it should be congratulated.

In late 2022, it came to my attention that a 78-year-old woman had bought a 1923 Daimler D16 landaulet, believed to be a unique survivor, and was selling the engine because she was converting it to electric power. The rationale was bizarre: modern cars are ugly, genuine Edwardian electric cars are too slow, double de-clutching is too difficult and she needed something in which her elderly Newfoundland dogs could travel comfortably… Even if such a conversion is reversible in theory, it is hardly so in practice when the original engine no longer remains to be reinstated.

Incidentally, the Daimler’s conversion was effected by a firm called Silent Classics, which claims that no modifications were made to the chassis. However, to add insult to injury, the converters had to make a public exhibition of their ignorance of and disinclination towards the original car, claiming in a YouTube video, that “it was impossible to change gear” and without power steering (which has been added, along with reversing sensors and an incongruous electric step) “you had to be the world’s strongest man to turn it.” It is sad that a couple of people too uncoordinated and feeble to drive a vintage car should blame their failings on the car and discourage the interest in others.

The 1929 Amilcar M with Weymann saloon bodywork which was sold from a French collection in 2018.

What can be done to stop the damage wreaked by unrepentant vandals? One can dream of some sort of official protections, as with listed buildings, which compel the owners of historic vehicles to recognise that, as custodians of the past, they cannot be permitted to destroy or fundamentally alter the objects in their care, but such are likely only to remain dreams. The Vintage Sports-Car Club has precisely the right approach in its policy of refusing eligibility to cars which have had their original bodies removed to make specials and disqualifying the guilty parties from membership. In the wake of the Patrick Hornet saga, it has been reassuring to see the Wolseley Hornet Special Club announce the same policy. We can only hope other clubs and event organisers follow suit. Certainly, the dubious appeal of a butchered Bentley would be greatly reduced if they were to be banned from racing at Goodwood or the Le Mans Classic and in rallies such as the Flying Scotsman.

An enthusiast bought the Amilcar, sympathetically recommissioned it but it was later offered by a European dealer without bodywork.

Of course, preservation does not end with simply keeping a vehicle together; it must be considered alongside restoration. Where a vehicle has deteriorated so far that parts are unsalvageable, restoration is a necessary accessory to preservation, but it is always a compromise. Restoration makes vehicles useable again and the value of a well-executed restoration to factory specifications cannot be overstated, but it unavoidably involves the erosion of historic material.

There is a priceless value in being able to study a car which retains its original paint, upholstery and trim. With modern paints and leathers differing greatly in composition from those used in period, the ability to study the original material and be able to say with certainty “This is how it was,” would not exist without enlightened efforts to preserve scruffy but sound vehicles in the most complete possible state of originality.

Sold at the Beaulieu Autojumble sale, the 1933 Wolseley Hornet Special with the restorable salonette bodywork by Patrick Motors which is now not on the car which has caused some criticism.

A final point to consider, and one for which at present there seems to be little enthusiasm, is that in instances where vehicles were historically modified, it may well be preferable to preserve the vehicle in its non-original but nevertheless historic guise than to attempt to simulate originality.

There are today dozens of vintage cars wearing nondescript tourer coachwork because the original bodies were discarded and the vehicles converted for commercial purposes at a stage in their life when they were of little historical or monetary value. Bullnose Morrises turned into farm hacks, Packards rebuilt as breakdown trucks and Rolls-Royces earning a sombre living as hearses were once common sights around Britain, but such vehicles have all but ceased to exist today.

This working-style tractor has had many improvements over the years such as a magneto conversion, which made it a better starter than with original trembler coils and it has pneumatic wheel conversions as well. The engine block has been frost-cracked and has been extensively repaired in preservation.

Likewise, pre-war Fords and Austins which really did have no value in the 1950s were imaginatively rejuvenated with fibreglass bodies, and veteran and vintage cars which were being rescued from dereliction were restored sometimes with a bit of artistic license with regard to their presentation.

What do you think about the American LaFrance fire engine conversions as authenticity just doesn’t count?

In all the cases described, the modifications represented an important stage both in the lives of the cars and in the social history of Britain before consumerism eroded the ‘make do and mend’ philosophy. It is to be hoped, although certainly not to be assumed, that if any Rolls-Royce with a home-made commercial body or a veteran De Dion-Bouton sporting a particularly jolly period paint job was to be discovered in generally sound condition, it would be sympathetically preserved on the strength of all that it represents.

This Bentley is now without its authentic body, which is being offered separately.

It is for that reason that one of the finest cars which I have been privileged to examine is a 1924 Rolls-Royce Silver Ghost which had been rebodied in 1950s by the Carr Bros garage business as a camera car, it is thought so that it might be hired out to film and television companies. It then spent 10 years with an owner who turned it into a caravanette before it was laid up in the 1960s and was offered for sale in 2014. Unsurprisingly, the first person to show an interest wanted to rip the body off and turn it into a generic tourer, so it was fortunate that it was rescued by a real enthusiast who has saved and put back on the road a unique piece of history.

Steam roller conversions are certainly going out of fashion, even if some look better than others.

Of course, each individual case should be approached with nuance and an undistinguished post-war body might justifiably be replaced if the owner means to faithfully replicate an original coachbuilt body, but it remains incontestable that to disregard and destroy both history and originality on a mere whim is reprehensible, and there ought to be no place in the hobby for owners who refuse to recognise the value of historic identity. The moral, then, is simple: respect history and cherish our inheritance – future generations will thank us.

This feature comes from the latest issue of Old Glory, and you can get a money-saving subscription to this magazine simply by clicking HERE

Previous Post

A real passion for Ford and Fordson tractors

Next Post

Some of the best Morris 6/8cwt Commercials models