Beautifully preserved 1949 Dennis Lancet III coach

Posted by Chris Graham on 8th March 2024

Zack Stiling spotlights a preserved 1949 Dennis Lancet III coach from an era when long-distance travel suggested glamour and excitement.

The Dennis Lancet III is supremely graceful from all angles.

The 1930s was the age of speed, luxury and elegance, and two industries which really embodied the aesthetic of the time were commercial air travel and motor coach travel, both of which had enjoyed rapid growth since the latter half of the 1920s. The prospect of flight caused greater excitement, but the coach industry benefitted from its influence. The stylists of the 1930s, enamoured with the thought of soaring through the skies, incorporated streamlining into everything, from cars and trains to architecture and household radio sets.

LJH 665 on Church Road in Willington, where it stopped to pick up schoolchildren, in 1969. (Pic: Nick Eagle Collection)

The coach industry, being reliant on impressing the public far more than other commercial-vehicle operators, was not indifferent to it, and the Art Déco coaches of the 1930s and 40s, such as this 1949 Dennis Lancet III, are some of the most beautiful commercials ever produced. With its alluring colour scheme and its gracefully slanted pillars, it could only have come from an age when walnut-effect Bakelite was finding its way into every home, and the skies over Croydon Airport buzzed with shining Dragon Rapides. The interior’s walnut veneer is not original, but it works to very good effect.

The 1930s fashion for streamlining is very much apparent.

Dennis produced its first purpose-made bus chassis, the E-type, in 1925, and the F-type of 1927 proved very popular as a platform for early coaches. The arrival of the fast-paced 1930s was heralded by the dynamic-sounding Dennis Arrow, of which only 58 were built up to 1934, when the much cheaper Lancet was introduced in its stead.

The Duple A-type body was extremely popular during the post-war period.

The Lancet was one of Dennis’s most popular passenger platforms in the 1930s, and after evolving into the Lancet II it survived until 1940, only to be revived in 1946 as the Lancet III. Despite the economic hardship of the immediate post-war period, Dennis found itself having to work hard to meet a sudden surge in demand. The British public, after six years repressed by the cruel demands of war, wanted to make the most of its hard-won freedom, and outings by coach, especially such glamorous ones as the Lancet, were one of the most pleasant ways of spending a weekend.

The Lancet worked for Lee’s for 23 years.

Whereas pre-war the Lancet II had been a single model with a range of options, the post-war Lancet range diversified into numerous different models, several of them export-only, but the Lancet III, or J3, was Dennis’s mainstay coach for the period and around 800 were built. There was no choice of engines; the J3 was solely available with the Dennis O6 six-cylinder, 7,580cc diesel. It was a strong motor, producing 100bhp and 328lb ft of torque, mated to a four-speed gearbox with overdrive. It used a twin dry-plate clutch, underslung worm-drive rear axle, semi-elliptic springs all round, worm-and-nut steering, twin rear wheels and hydraulic drum brakes with servo assistance. The chassis had a wheelbase of 209in and overall length of 322½in, contributing to a passenger capacity of roughly 32 people.

When it was new, there was great prestige attached to luxury coach travel.

This Lancet is owned by Mark Smith, who also owns the 1931 Bedford bus featured a few issues ago. The contrast between the small and very rudimentary village bus and the luxurious and stylised Dennis could hardly be greater. It sports a curvaceous Duple A-type body, Duple’s full-sized offering which was widely used by most British coach manufacturers. Like the Lancet III, it was introduced in 1946 but had pre-war origins.

The subtly tapered radiator made Dennises of the 1930s and ’40s very distinctive.

LJH 665 was supplied new to Lee’s Luxury Coaches Ltd. of High Barnet, Hertfordshire, which had recently been taken over by Horseshoe Coaches of Tottenham. Horseshoe expanded significantly in the post-war years having done extremely well out of wartime government contracts. It became a very large operator, with 45 coaches by 1952, including several other Duple-bodied Lancets, plus one with a Yeates body, finished in Horseshoe’s attractive two-tone blue.

Flashing indicators were fitted while the coach was still in service.

As befitting such a handsome and well-appointed coach, its early life was spent on fairly prestigious engagements, such as taking racegoers to Epsom Downs for the Derby. It was eventually demoted, but it gave a good 17 years of service before it was transferred to Horseshoe’s contract fleet at Kempston, Bedfordshire, in 1966. Henceforth, it would be reserved for contract hire with the Marston Valley Brick Co. and local schools, ferrying workers and schoolchildren from the villages around Bedford to the brickworks and the various schools.

There are no angles – every detail is awash with beautiful curves.

In 1969, the Lancet had reached the end of its life, as far as Horseshoe was concerned. Around Eastertime, it was withdrawn from service and sold for scrap. It somehow evaded death and was saved for preservation in the 1970s by Mr. Kershaw of Northwich, Cheshire, an enthusiast who also saved at the same time LFM 302 and LFM 320, a pair of ex-Crosville Weymann-bodied Leyland Tigers which had joined the Horseshoe contract fleet. LJH 665 then dropped off the map until it was acquired in the late 1990s by Stephen Morris of the Quantock Heritage Fleet in Somerset, who had it restored by Cobus. It later joined the fleet of Goodwins Coaches in Manchester, before being added to the eclectic private collection of Mark Smith in 2015, where it lives among his collection of other interesting historic vehicles.

The dynamic side spears culminate in Duple Coachwork badges.

Since then, it’s been widely rallied and has given good service. Mark says, “Since we’ve had it, bodily-wise nothing’s been touched, but mechanically the engine has been completely rebuilt. We rebuilt it after I’d spent a considerable amount of time trying to locate brand-new old-stock parts, like pistons, liners, big-end and main bearings. When the engine was stripped, we found the crank wasn’t true, so that had to go to Sheffield to be straightened. Various other bits and pieces we had to have machined because we couldn’t find them. It was off the road for three to six months while we did that. We also spoke to the Dennis Society and they were helpful. Obviously there are not many of these vehicles around so parts are very scarce.”

The wheel trims are simple but enhance the sleek appearance.

Always maintained and kept in use, it’s been a pleasure to drive. According to Mark, “The O6 engine is Dennis’s own, but it’s very similar to a Gardner of the same era. It has four valves per cylinder, so in the 1940s it was quite ahead of its time. Transmission-wise, the gear-change mirrors the usual arrangement, so first gear is in the usual third-gear position, and so on. When you’re in fourth, which is where you’d expect second, you push the lever across to the left and forward to put it in overdrive. It’s not off at the traffic lights like a scalded cat, but it’ll travel quite happily between 50 and 60mph until it gets any indication that there’s a gradient. You as a driver might not realise you’re climbing a hill, but the engine will tell you. It’s got vacuum-assisted brakes so you’ve got a good, rock-hard pedal, but you’ve still got to look way into the distance and start braking – you won’t stop it on its nose. Steering-wise, as long as you’re moving it’s relatively light, but if you’re trying to manoeuvre it, especially with a full load of people, then it’s very heavy indeed.”

Decorative marquetry enhances the Art Déco glamour of the interior.

It was the Dennis’s good fortune that Mark had brought it ‘home’ to Bedfordshire. There was a surprise in store when he took it to a show at Old Warden a few months after buying it. “One of the kids who went to school in it in the 1960s, who was then getting towards retirement age, couldn’t believe his eyes when he saw his old school bus at the show. He phoned one of his old school chums and said ‘What are you doing today? You really ought to come to Old Warden because our old school bus is here. You’ll never believe it.’”

With its curvaceous sliding door and shining aluminium steps, entering the Lancet feels almost futuristic.

The ex-schoolboys were Merv Askew and Nick Eagle, both lifelong bus enthusiasts. Nick had been a passenger on the Lancet’s final journey with Horseshoe in the Easter of 1969, when the driver told him it was about to be scrapped and that he would be welcome to strip it of some of its smaller parts to keep as souvenirs. Grabbing a screwdriver from his dad’s shed, he saved the roller blind, one of the Duple badges and the Lancet badge from the grille.

Stylish Smiths clock is very much of the period.

Merv remembers well his journeys from Willington to Stratton Technical Grammar School in Biggleswade every morning: “Horseshoe had the contract to take children in from the Bedford area. It used to send 10 coaches from Bedford through the villages and up the A1 to Biggleswade. One day this vehicle turned up. It always had the same driver, who was called Derek. He was a real character, he didn’t pull any punches when driving it. They used to sit three children to a seat and at the time the A1 was a dual carriageway – you used to see two buses travelling side by side.”

Clayton heater ensures passengers can travel in comfort all year round.

Nick lived a few doors away from Merv and attended Abbey County Secondary School in Elstow, a village just outside Bedford, from 1964 to 1969. He recalls, “We were always interested in buses. Merv’s dad took us down to London a couple of times when we were kids and we’ve got pictures of Horseshoe’s depot in Tottenham in the 1960s. Merv was more interested in buses and I was more interested in lorries, and we spent most weekends watching them. When we were kids, we had cardboard cut-outs of the fronts of lorries or buses hanging on our bikes – that was us going out for a drive.”

The walnut may not be completely original, but it certainly looks the part.

Nick remembers the best coaches being reserved for the grammar school, whereas the boys of the secondary modern were generally relegated to more utilitarian, rear-entrance buses which had been to the brickworks and were covered in brick dust. However, LJH 665 alternated weekly between the two routes. As Nick explains, “The driver we had, Bill Clark, was Horseshoe’s mechanic. After the school run he’d be working on buses, and the following day we were the road test. Bill would come round with whatever one he’d been working on. Mrs Clark was the attendant. We’d have Bill one week and a man called Cyril the second.

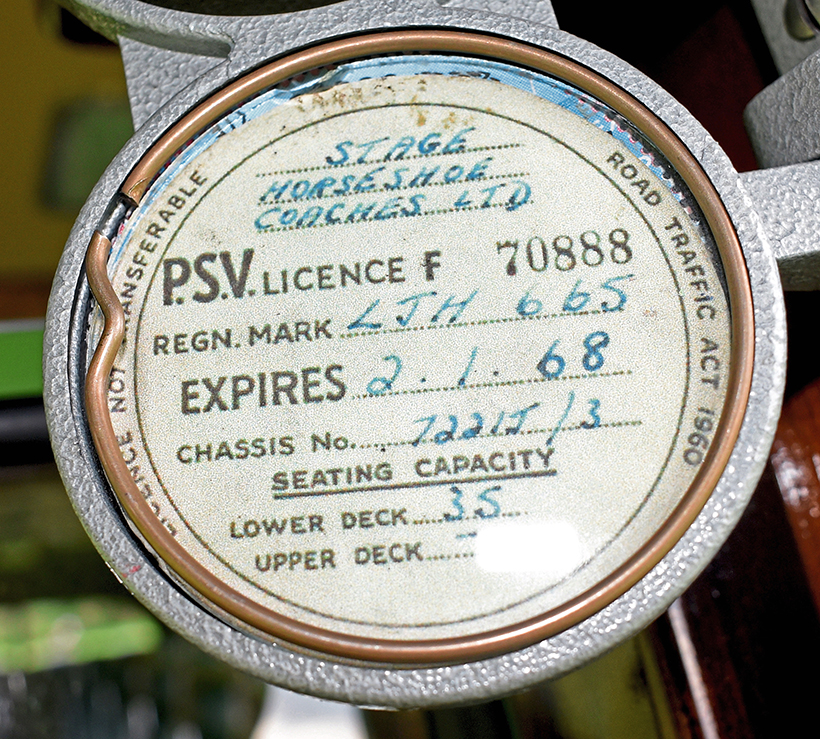

This Duple plaque was kept as a souvenir by Nick Eagle for 46 years.

“The bus used to absolutely fly with certain drivers. Coming to Bedford, there was a railway bridge which had a bend on top of it where the driver used to catch the back wheel on the kerb and throw all the kids across the coach…”

Returning to 2015, Merv and Nick were involved with running a transport day in Willington. When Nick met Mark at Old Warden he said, “I’ve still got the roller blind and badges at home. If you’ll come to Willington, I’ll present them to you and you can put them on it.” That Mark duly did, and was shown pictures of the Lancet outside Nick’s house for the school run.

Rarely does one encounter such elegant seats.

One day, Mark arranged to recreate these old pictures. He says, “We parked in the village outside Nick’s mother’s house where it would park to pick up kids. We were taking pictures and this lady turned up and said ‘Can I ask what’s going on?’ We said, ‘Well, this is the old school bus,” and she said, “I know it is, my dad used to be the driver.”

Period tax disc commemorates the last years of the Lancet’s working life.

“Nick was going to retire,” continues Mark, “and his wife said it’d be lovely if he could have the old bus pick him up, so they found all of Nick’s family and people he’d worked with, and I ended up picking him up on his last afternoon from work. He couldn’t believe what was going on. I took them out for a run, stopped at one of the tea rooms and they had afternoon tea and cakes.”

Mark Smith has been preserving the Lancet for nine years.

When visitors to a transport rally come upon vehicles like the Dennis, many will stop and appreciate it for its beauty, but it’s easy to forget just how important they were. Without coaches like it taking thousands of children to school and workers to their jobs, modern Britain couldn’t have developed as it did. No less important, though, is the happiness they brought, and continue to bring, to those who travelled on and worked with them, and maybe that’s the most important reason why we must cherish and preserve them.

This feature comes from the latest issue of Old Glory, and you can get a money-saving subscription to this magazine simply by clicking HERE

Previous Post

Restoring a superb, 1941 Bucyrus-Erie 10-B excavator

Next Post

The Jim Russell sale of amazing tractor models